While many nationalities were represented by the adventurers and treasure seekers who flocked to Chiriquí, numerous British and American gentleman's magazines, newspaper articles, and antiquarian reports in particular detailed and propagated the looting of tens of thousands of Chiriquí graves in the 1859-1860 gold rush (The use of the term 'looting' is potentially inappropriate here as at the time of the Chiriquí gold rush, the removal of the artifacts was not illegal. As Julie Hollowell (2006, 98) points out, "we tend to characterize all undocumented digging as illicit looting", but this is not always the case in contemporary or historical contexts if no laws are broken by the activity. Does the nineteenth century gold rush qualify as looting or is some other term more appropriate to use?). These accounts provided interwoven, contradictory, and overlapping stories of the discovery of great quantities of gold (e.g. Anon 1859a ![]() ; Anon 1859b

; Anon 1859b ![]() ; Anon 1859c

; Anon 1859c ![]() ; Anon 1859d

; Anon 1859d ![]() ; Anon 1859e

; Anon 1859e ![]() ;

1859f

;

1859f ![]() ; Anon 1859g

; Anon 1859g ![]() ; Anon 1859h

; Anon 1859h ![]() ;

Bateman 1860

;

Bateman 1860 ![]() ;

Blake 1863

;

Blake 1863 ![]() ;

Bollaert 1860

;

Bollaert 1860 ![]() ;

Merritt 1860

;

Merritt 1860 ![]() ;

Taylor 1867

;

Taylor 1867 ![]() ).

).

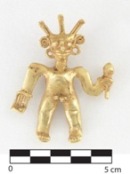

Figures 3-6: Chiriquí gold artefacts. Courtesy, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (Catalog Numbers: 008267.000, 008277.00, 034878.000, 232150.000)

Stories, rumours, and legends abounded regarding Chiriquí gold in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As graves were generally not marked above ground, their detection usually occurred when subsoil exploration encountered the capping stones characteristic of Chiriquí grave construction. One common narrative of discovery recounts a purposeful expedition to find graves in a remote area; the efforts are interrupted by dwindling supplies and return trips to relocate the site are unsuccessful and end with the injury or loss of one of the party (e.g. Lothrop 1919, 28-34). Other frequent narrative structures entail accidental and surreptitious discovery of great wealth. One such story is detailed in Harper's Weekly by Otis (1859, 499-500 ![]() ) in a description of grave offerings inadvertently uncovered by the overturning of tree roots during a storm leading to the recovery of hundreds of 'images, most of which proved to be of the finest gold' (also Bollaert 1860, 46

) in a description of grave offerings inadvertently uncovered by the overturning of tree roots during a storm leading to the recovery of hundreds of 'images, most of which proved to be of the finest gold' (also Bollaert 1860, 46

![]() ; Merritt 1860, 3

; Merritt 1860, 3 ![]() ; Taylor 1867, 78

; Taylor 1867, 78 ![]() ; [View Comments]). Even accounting for exaggeration and very disparate valuations of the artefacts removed, considerable wealth was derived from the Chiriquí looting. A reported £10,000 pounds of Chiriquí gold objects were melted annually by the Bank of England during the peak of the gold rush (Lothrop 1948, 162); this sum represents a contemporary value of roughly £6,732,000 (or $10,950,000 USD) of gold extracted per year if calculated using an average earnings index (Officer 2009) and of course does not represent the amount of gold removed but unreported. Banks and corporations financed ships and took large shares of the gold removed from Chiriquí, with familiar contemporary corporate names like American Express and Wells Fargo accorded large portions of the published proceeds.

; [View Comments]). Even accounting for exaggeration and very disparate valuations of the artefacts removed, considerable wealth was derived from the Chiriquí looting. A reported £10,000 pounds of Chiriquí gold objects were melted annually by the Bank of England during the peak of the gold rush (Lothrop 1948, 162); this sum represents a contemporary value of roughly £6,732,000 (or $10,950,000 USD) of gold extracted per year if calculated using an average earnings index (Officer 2009) and of course does not represent the amount of gold removed but unreported. Banks and corporations financed ships and took large shares of the gold removed from Chiriquí, with familiar contemporary corporate names like American Express and Wells Fargo accorded large portions of the published proceeds.

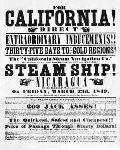

One mail ship alone, the Star of the West, arrived in New York City's port from Panamá with a reported '$1,863,691 in treasure' (Anon 1859b ![]() ). Interestingly, the 'treasure' included in this published sum was carefully tabulated by a purser without distinguishing between mined gold from California – where the gold rush began a decade prior to that in Chiriquí – and looted gold artefacts from the Chiriquí gold rush. The isthmus of Panamá served as one popular route for travel of gold and gold-seekers from the East Coast of the United States to California. This trip was first completed by mule and canoe and then by means of the Panama Railway across the isthmus, once it was built in 1855; the two gold rushes were thereby historically linked.

). Interestingly, the 'treasure' included in this published sum was carefully tabulated by a purser without distinguishing between mined gold from California – where the gold rush began a decade prior to that in Chiriquí – and looted gold artefacts from the Chiriquí gold rush. The isthmus of Panamá served as one popular route for travel of gold and gold-seekers from the East Coast of the United States to California. This trip was first completed by mule and canoe and then by means of the Panama Railway across the isthmus, once it was built in 1855; the two gold rushes were thereby historically linked.

Figure 7: An 1849 handbill from the California Gold Rush advertising ship passage between New York and California; Wikimedia Commons

The comments facility has now been turned off.

| To separate out one of these examples, the Bollaert 1860 account was published in The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Review. This series ran from July 1856 to May 1868 and was part of The Gentleman's Magazine founded in London in 1731 (by Edward Cave using the pen name Sylvanus Urban; all subsequent editors also used the same name). The intention of the magazine was to create a monthly digest of any news the educated public might find of interest. The frequently sensationalised archaeological reports of such magazines, however, raise the question of what role popular media accounts, personal narratives, and rumour should play in archaeological assessments. I invite discussion regarding this issue: do such accounts provide texture and subtext or only entertaining background noise? How do they differ or parallel what we see daily on the Discovery Channel or other educational yet frequently sensational outlets for archaeological discussion? | Karen Holmberg |

| In section 1.1, "Narratives of discovery and wealth," you bring up an important point in questioning the appropriateness of the term "looting." For me this passage raised larger questions of what we choose to value and why. In your example, the issue at stake is how to understand the appropriation of local artifacts prior to the passage of legislature outlawing it. At the time, those committing the act probably viewed the artefacts as valuable commodities while ignoring their less qualitative aspects of cultural and historical value. Parallels can be drawn to other acts of cultural destruction and defamation, such as the loss of the giant Buddhas in Afghanistan at the hands of the Taliban. I think a key underlying factor in why events like these occur is that heritage is, to some degree, a social construction. Value is a process (your phrase, I think?) - a contract, almost, by which people agree to regard an artefact a certain way in order reify it as something greater than its intrinsic worth. When this contract is broken, destruction ensues.

On a different note, you mentioned in class that many scholars have overlooked this area because it is "impure," but I think that the "gold rush" in Chiriqui adds a unique wrinkle to the local history and heritage, which made the narrative of your article very engaging. | Misa S |

| To respond to the authors question "do such accounts provide texture and subtext or only entertaining background noise?" I submit that such accounts provide important textual information to a situation.

For one they set the context of the current social setting. Regardless of the source there is always some information that can be discerned. For instance a rumor spread throughout the community may not be information in itself, but the very existence of the rumors tells us something about perception of the subject. This type of 'unofficial' information is even more important when it may represent fragments of the actual culture of the place. While greatly diminished these type of sensational stories occasionally represent the remnants of cultural oral histories. Much like the Western interpretation of ethno-histories and mythology this type of information has to be understood in the social context of the culture and interpreted as a combination of history, religion, science, and society. | Noa Lincoln |

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s)

University of York legal statements | Terms and Conditions

| File last updated: Mon Oct 11 2010