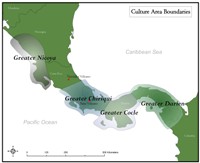

Figure 31: The Chiriquí culture area and nearby culture areas

Current trends in the social sciences highlight the concept of 'unsettling' established notions of place and other conceptual categories by questioning accepted notions of archaeological cultural areas and static interpretations of them (e.g. Bailey et al. 2005). Perhaps it is hence desirable rather than problematic that the definition of the Chiriquí culture area, which is based upon ceramic characteristics, is a spatially debatable one and its borders are best seen as mutable and porous. The lack of spatially accurate conceptions of where archaeological sites are or once were, however, is more problematic when trying to ascertain the relationship of systematic archaeological projects to looted sites and looted materials.

The 'archaeological problem of Chiriqui' was framed in an article in American Antiquity by Cornelius Osgood (1935), curator of the Yale Peabody Museum from 1934-73, and references his difficulty in assigning a 'place' for Chiriquí artefacts; an intense material richness divorced from spatial context is still the 'archaeological problem of Chiriquí'. While the museum collections' de-contextualised looted objects formed the basis for important studies of Chiriquí ceramics (Holmes 1888; MacCurdy 1911 ![]() ; 1913

; 1913

![]() ; Osgood 1935

; Osgood 1935 ![]() ; Shelton 1984), the objects lack any contextual connection to the Chiriquí landscape and the collections are devoid of spatial relationship to one another. Though not discarded, the artefacts are effectively removed from archaeological investigation.

; Shelton 1984), the objects lack any contextual connection to the Chiriquí landscape and the collections are devoid of spatial relationship to one another. Though not discarded, the artefacts are effectively removed from archaeological investigation.

The gentleman's magazines and newspaper reports that recorded the large-scale 19th-century looting in Chiriquí provided little detailed information regarding the precise location of archaeological sites. Frequently, descriptions were given in these accounts by persons who had not actually visited the sites but who gave accounts derived from rumour, hearsay, or second-hand information. Confusion and conflation, for example, seemingly occurred in many of these accounts regarding whether two separate sites named Bugaba and Bugavita exist near one another, whether they were the same site, or if multiple sites near the town of Bugaba were simply given the names as a descriptor. Some antiquarian or early archaeological accounts gave very helpful descriptions (e.g. Linné 1936, 98) of sites they visited, though these also suffer from a large degree of variation in the level of detail and frequently lack designation of whether site descriptions are the product of personal visits or second-hand accounts (see Osgood 1935 ![]() ; Wassén 1949

; Wassén 1949 ![]() ). One aspect of my own project, therefore, entailed the attempt to query museum accession files in addition to the varied published descriptions for any recorded spatial data. Particularly in the case of objects amassed by J.A. McNeil and held by the Smithsonian Institution, Harvard Peabody Museum, and Yale Peabody Museum, some accession files contain rough map coordinates, distances from the Chiriquí city of Davíd, or descriptions of landscape markers such as rivers or hills that I used to extrapolate estimated site locations. It is unclear whether an exceptionally prolific grave opener like J.A. McNeil would seek to protect a rich grave location by obfuscating its location; if he did not, it is uncertain how accurate his reported locations might be. Whether McNeil carried a map with him to record locations while he opened graves or instead assigned approximate locations much later is not readily apparent from museum accession files.

). One aspect of my own project, therefore, entailed the attempt to query museum accession files in addition to the varied published descriptions for any recorded spatial data. Particularly in the case of objects amassed by J.A. McNeil and held by the Smithsonian Institution, Harvard Peabody Museum, and Yale Peabody Museum, some accession files contain rough map coordinates, distances from the Chiriquí city of Davíd, or descriptions of landscape markers such as rivers or hills that I used to extrapolate estimated site locations. It is unclear whether an exceptionally prolific grave opener like J.A. McNeil would seek to protect a rich grave location by obfuscating its location; if he did not, it is uncertain how accurate his reported locations might be. Whether McNeil carried a map with him to record locations while he opened graves or instead assigned approximate locations much later is not readily apparent from museum accession files.

Effectively this exercise utilises GIS – once described as the 'quantifier's revenge' on postmodernists (Oppenshaw 1991, 621) – to query the role or usefulness of the unquantifiable entity of rumour and hearsay. While the usefulness of this may be questioned by anyone demanding ground-truthed, precise coordinates, I argue that the ability to make that which is elusive – extant and heavily looted sites – more 'material' and 'placed' has a significant utility in providing a graphic conception of where Chiriquí collections were obtained. The locations are largely lost from local memory and the creation of such a map provides a perspective of where looted areas are located in relation to systematically investigated areas. These looted site locations evidence what Soja (1996, 81) termed a third space, or 'a remembrance-rethinking-recovery of spaces lost ... or never sighted at all' that recent studies (e.g. Fitzjohn 2009) are beginning to query.

The comments facility has now been turned off.

| Utilising data within a GIS environment is a good example of literally going beyond what we tend to conventionally consider the map. It is more than a 'graphic' which is a map as a representation only, it is also a map for intervention. Counter-mapping and materialising the Other even though they are representations is that there are associated consequences. Consequence clearly lies at the center of the project of 'placing' both the material and immaterial, whereby the action of looting brings into force the notion of collecting as memory. Furthermore, thinking about the role of intervention as a kind of mapwork means that the 'static' site with which place so often becomes associated with, is turned on its head: we begin to see the dynamic and active nature of its creation as a processes of flows in, out and through only some of which become solid, or emplaced. In fact, with greater resolution (facilitated by GIS or other kinds of mapwork) of the Chiriqui landscape we begin to see the fallacy of defining cultural areas, or at the very least assuming continuity without change. The Chiriqui landscape is constantly being disrupted and made unstable, being reconstituted and forged in new ways through time. But while I might question the continuity at a generalised level in any landscape, using the map to rematerialise the immaterial (either immaterial practices or things forgotten) clearly makes connections between what we would define as different temporal episodes. But an important connection is between materialised practices that have been forgotten and their rematerialisation through archaeological practices. The binding agent in this process is intervention demonstrated here by Karen in her archaeological survey and archive work and in the mapping of these sites. Intervention is not either just about technique or what kind of practice is being performed, although these have effect on what is done and revealed, but it is about the consequences of this work and how this intervenes in what we do and interpret. Are we representing worlds or creating them? Clearly a bit of both. In the making of our archaeological objects (the sites that have been mapped through survey) in a process of materialising what has been forgotten we are rematerialising the past and in a small way the intentionality of its people through mapwork; the ontology of which is flat and thoroughly archaeological. | Oscar Aldred |

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s)

University of York legal statements | Terms and Conditions

| File last updated: Mon Oct 11 2010