Cite this as: Biddulph, E. 2015, Pottery production at Heybridge, in M. Atkinson and S.J. Preston Heybridge: A Late Iron Age and Roman Settlement, Excavations at Elms Farm 1993-5, Internet Archaeology 40. http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.40.1.biddulph

Pottery production at Heybridge is attested by the presence of four pottery kilns. The largest volume of pottery was recovered from the paired-kiln complex in the hinterland zone of Area W. Two kilns were uncovered in the southern zone: one in Area L and the other in Area N. The latter yielded the least evidence, consisting of undiagnostic spalled sherds only. Consideration here is given to the pottery recovered from the kilns, incorporating the identification and quantification of products, dating of kiln use, and an overview of pottery production at Heybridge and its regional setting. The identified vessels have been ordered into classes following the Chelmsford typology (Going 1987, 13-54).

Descriptions of the kiln product fabrics are based on the scheme outlined by Peacock (1977c, 26-33). Munsell colour references are additionally employed. The pottery from Area W stoke-hole 1589 is fully quantified and published as a key pottery group (KPG27), including non-kiln products, and presented in the Pottery sequence section. Selected sherds from the Area W and Area L kilns were thin-sectioned at the Department of Archaeology, University of Southampton (D.F. Williams; report in archive). It was noted that the coarse ware sherds were in a reduced sandy fabric with visible quartz grains together with some small pieces of flint. A mortarium from kiln 1618 had a similar, but light-coloured, fabric, with fewer flints. Dr Williams concludes that since Heybridge is situated in an area of London Clay, covered in part by boulder clays and brickearth, the clay used in the pottery seems to reflect a certain intermingling of sources.

At Crescent Road, Heybridge, Wickenden identified an assemblage of some 4500 sherds as 'the discarded products from a nearby kiln' (1986, 46), dating their manufacture to the mid-3rd century. The material has been re-examined and the conclusion is that since the pottery was small and abraded rather than spalled or overfired, it could not be positively identified as waste products from a nearby kiln. The evidence concerning mid-3rd century production here must remain inconclusive. However, the fabric of much of this pottery was similar to that of Elms Farm kiln products, particularly from Area N, suggesting, at least, an identical clay source and, therefore, local production.

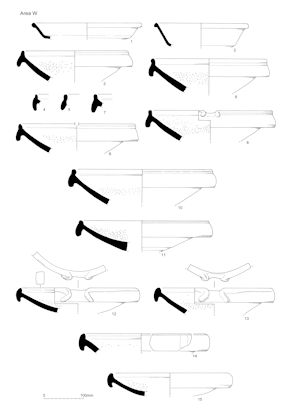

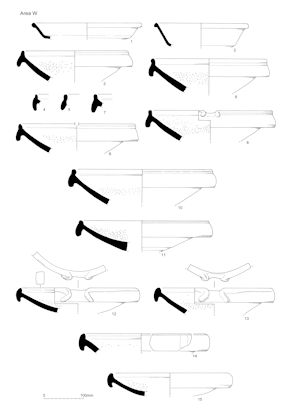

Kiln 1223 (Group 908) yielded the least amount of pottery, 3500g, and kiln 1618 (Group 906) contained the most, totalling 27,740g. Their shared stoke-hole, 1589 (Group 910), contained just under 12,000g. Buff ware mortaria and grey ware, including many spalled and overfired sherds that have been identified as locally produced kiln products, formed the largest components of the three pottery assemblages. By weight, 69% of the total volume of grey ware was recovered from kiln 1618, as compared to 28% in the stoke-hole and a meagre 3% in kiln 1223. Buff ware mortaria were present in similar proportions; 65% was recovered from 1618, 24% from 1589, and 11% from 1223. Kiln 1618 thus produced the most extensive range of products and best dating evidence.

A somewhat limited range of forms was evidently produced, predominantly jars, including ledge-rimmed types and high-shouldered varieties with undercut rims. Folded beakers and bead-rimmed dishes were also manufactured. Mortaria sherds, comprising hammerhead-rimmed and bead-and-flanged types, were built into the structure of kiln 1618, perhaps inserted as repair or to aid firing. These, too, could originally have been fired in this kiln. In contrast to 1618, the paucity of vessels from kiln 1223 provides little clue as to what was fired in it.

The minimum vessel number was calculated for the kiln products in sandy grey ware and buff ware only, which were visually distinctive. Fine grey ware was invariably abraded and products in this fabric could not be separated easily from any non-kiln fine grey wares. An accurate count of certain fine grey ware kiln vessels, mainly B2 or B4 dishes, is likely to be higher than the six vessels actually counted.

This gritty fabric has dark grey brown surfaces (2.5Y 4/2), in which frequent small white and grey quartz grains, less than 1mm in size, and occasional flint pieces up to 5mm long, are visible. The core is darker grey (2.5Y 4/0). Frequent white, grey and black inclusions are well sorted, though larger angular clear quartz grains are also present. Totals are 488g from 1223, 10247g from 1618, and 4158g from 1589.

Forms: Dish B2/B4, jars G5.5 G25, beaker H35

Surface and core colours are as for GRS; however, inclusions are generally finer and more frequent, and when seen microscopically, have an appearance reminiscent of Hadham grey ware (see Fabrics) No flint or quartz grains are visible on the surfaces. Examples are in poor condition and invariably abraded and powdery.

Forms: Dish B2/B4, beakers H21 H35

This fabric, which is soft and invariably powdery, varies from light green- or brown-grey (5Y 7/2, 10YR 7/2) to yellow-brown (10YR 7/6). Inclusions of fine sand, and occasional mica and iron-rich particles, pink clay pellets and flint; trituration grits of angular white, grey and black flint, 2-5mm in diameter, and sparse white quartz. Traces of a dark yellow-brown (10YR 4/6) slip are visible on the external and internal surfaces of some examples. Totals are 1611g from 1223, 10310g from 1618, and 3860g from 1589.

Forms: Mortaria D3 D11 D13

B2/B4

Bead-rimmed dish with tapering sides and flat base. Most examples were recovered from kiln 1618, and mainly comprised rim sherds that could not be positively identified either as the shallow B2 or the deep B4 type. Principally a fine grey ware product.

D3

Mortarium with incurving, droopy flange and high, delineated bead. Examples vary in height of the bead and diameter, which ranges from 280 to 360mm. The form, with its rather upright flange, is akin to the D11 hammerhead-rimmed mortarium. It differs in this respect from D3 mortaria at Chelmsford, whose flanges are set more horizontally. No precise parallel, in fact, has been found at Chelmsford or Colchester. Never common, the type was nevertheless recovered in similar quantities from kiln 1618 and stoke-hole 1589. None was found in kiln 1223.

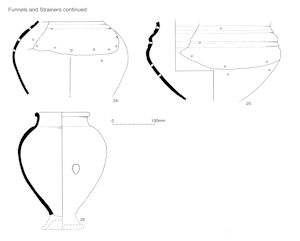

D11

Hammerhead-rimmed mortarium. Examples display considerable variation in size and shape, but are generally characterised by upright rims with flat tops. Some have curving and hooked flanges, closely resembling Chelmsford form D11.1. The smaller D11.2 is also represented. Some examples have wider 'bevels' at the top of the rim, while others are particularly large and robust, with no curve to the flange. The form was undoubtedly more common than the D3 mortarium. Kiln 1618 and stoke-hole 1589 yielded the most examples, while 1223 yielded the least.

D13

Wall-sided mortarium with small spout and grooves at the top and bottom of the flange. Just one example was recovered, from pit 1621 cut into the stoke-hole 1589. Its fabric is a little coarser than is usual for buff ware mortaria, either from these kilns or Colchester. However, it is deemed a local product on the basis of its affinities with an example recovered during the Crescent Road excavations. Both are hard and gritty, and off-white to grey in colour. The latter example was thought to be a non-Colchester product, probably dating to the early 3rd century AD (Wickenden 1986, 40, fig. 21.137).

G5

Ledge-rimmed, high-shouldered and neckless jar resembling Chelmsford forms G5.5 and G5.6. The G5.5 was made in two sizes - large (diameter of 140-180mm) and small (diameter of c. 100mm). The large G5.5 is notable for its consistent design; the ledge rim is created by a thin groove, rather than a gentle cupping, characteristic of the G5.5 at Chelmsford. No lids were found in either the kilns or stoke-hole, and it seems unlikely that ceramic lids were made to fit the form. The G5 type was made at Mucking (Rodwell 1973, 22), Grays (Rodwell 1983, 27), and Orsett (Rodwell 1974, 27), all in South Essex.

G24

Oval bodied jar with everted, slightly undercut, rim. A thin cordon appears on the short neck. Examples from these kilns are few in number, but the form was otherwise common at Heybridge.

G25

Jar with undercut rim, short neck and grooved shoulders. The type produced at Elms Farm resembles Cam 268B, a very prolific form at Colchester (Bidwell and Croom 1999, 479), and corresponds closely with Chelmsford form G25.1. Its size varies; diameters range from 140 to 180mm.

H21

Cornice-rimmed, bag-shaped beaker, with band of roller-stamped decoration on body. Its presence is restricted to a single example. This is abraded and burnt, but traces of an external slip survive. Roller-stamped body sherds were present in numerous contexts, but could not be confidently identified as H21 beakers. The form was also produced at Ivy Chimneys, Witham (Turner-Walker and Wallace 1999, fig. 114.25)

H35

Large folded beaker with short neck, bead rim, and roller-stamped decoration on body. Examples are burnt and abraded, and only tentatively identified as local products.

H (unclassified)

A single example of a small ledge-rimmed vessel, with a short neck, was recovered from stoke-hole 1589. This was identified as a local product on the basis of fabric. The form is unparalleled, although clearly resembles ledge-rimmed jars. Diameter 92mm.

Cam 370

Large double-handled flagon with heavily reeded rim. The single example present was set into the pedestal of kiln 1618. The rim of the flagon is warped, and its fabric identical to that of other grey ware products. The flagon may well be a waster product from a previous firing within this kiln, placed in the pedestal as repair. Alternatively, it might be from another and earlier, as yet undiscovered, kiln in the vicinity. The form is absent at Chelmsford, but present at Colchester, albeit poorly represented in a coarse oxidised ware only.

S (unclassified)

Body sherds from two examples of a curiously shaped vessel were recovered. The sherds are thick-walled, cylindrical and decorated with a band of rouletting. As no rim or base sherds were found, the form or function is impossible to discern. Its cylindrical shape and decoration suggest a beaker, although it is remarkably robust. It may have been placed in a kiln as a support or bar, but it is wheel-made and shows no signs of repeated firings. It may have functioned simply as a test-piece prior to the firing of a whole load. Its fabric, too, is typical of kiln products.

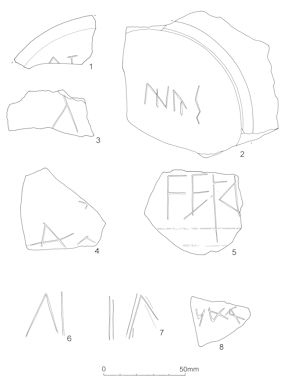

| Number | Context | Feature | Fabric code | Form |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1517 | 1618 | GRS | Dish B2 |

| 2 | 1533 | 1618 | GRF | Dish B4 |

| 3 | 1619 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D3 |

| 4 | 1518 | 1589 | BUFM | Mortarium D3 |

| 5 | 1518 | 1589 | BUFM | Mortarium D3 |

| 6 | 1619 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D3 |

| 7 | 1213 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D3 |

| 8 | 1027 | 1589 | BUFM | Mortarium D3 |

| 9 | 1002 | 1589 | BUFM | Mortarium D3 |

| 10 | 1512 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D3 |

| 11 | 1211 | 1589 | BUFM | Mortarium D3 |

| 12 | 1512 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 stamped |

| 13 | 1619 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 14 | 1213 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 15 | 1518 | 1589 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 16 | 1615 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 stamped |

| 17 | 1213 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 18 | 1002 | 1589 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 19 | 1533 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 20 | 1029 | 1223 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 21 | 1029 | 1223 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 22 | 1002 | 1589 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 23 | 1211 | 1589 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 24 | 1029 | 1223 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 25 | 1615 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 26 | 1615 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 27 | 1581 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 28 | 1615 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 29 | 1615 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 30 | 1164 | 1223 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 31 | 1517 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 32 | 1211 | 1589 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 33 | 1615 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 34 | 1615 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 35 | 1615 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 36 | 1581 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 37 | 1512 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 38 | 1581 | 1618 | BUFM | Mortarium D11 |

| 39 | 1620 | 1621 | BUFM | Mortarium D13 |

| 40 | 1534 | 1618 | GRS | Jar G5.5 |

| 41 | 1518 | 1589 | GRS | Jar G5.5 |

| 42 | 1518 | 1589 | GRS | Jar G5 |

| 43 | 1539 | 1618 | GRS | Jar G5 |

| 44 | 1211 | 1589 | GRS | Jar G5 |

| 45 | 1002 | 1589 | GRS | Jar G5 |

| 46 | 1002 | 1589 | GRS | Jar G5 |

| 47 | 1502 | 1589 | GRS | Jar G5.6 |

| 48 | 1002 | 1589 | GRS | Jar G23/G24 |

| 49 | 1518 | 1589 | GRS | Jar G25.1 |

| 50 | 1539 | 1618 | GRS | Jar G25.1 |

| 51 | 1539 | 1618 | GRS | Jar G25.1 |

| 52 | 1517 | 1618 | GRS | Jar G25.1 |

| 53 | 1539 | 1618 | GRF | Beaker H21 |

| 54 | 1029 | 1223 | GRS | Beaker H35.2 |

| 55 | 1576 | 1618 | GRS | Beaker H35.2 |

| 56 | 1518 | 1589 | GRS | Beaker |

| 57 | 1615 | 1618 | GRS | Cam 370 flagon |

| 58 | 1576 | 1618 | GRS | Cylindrical rouletted body sherd |

| Kiln 1223 | Kiln 1618 | Stoke-hole 1589 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVE | % EVE | EVE | % EVE | EVE | % EVE | Total | |

| B2/B4 | - | - | 0.48 | 5 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.54 |

| D11 | 0.64 | 84 | 2.70 | 26 | 1.40 | 33 | 4.74 |

| D3 | - | - | 0.58 | 5 | 0.49 | 12 | 1.07 |

| G24 | - | - | 0.14 | 1 | - | - | 0.14 |

| G25 | - | - | 1.13 | 11 | 0.09 | 2 | 1.22 |

| G5.5 | - | - | 3.48 | 33 | 1.49 | 35 | 4.97 |

| G5.5 (small) | - | - | 0.72 | 7 | 0.41 | 10 | 1.13 |

| G5.6 | - | - | - | - | 0.11 | 3 | 0.11 |

| H21 | - | - | 0.17 | 2 | - | - | 0.17 |

| H35 | 0.12 | 16 | 0.17 | 2 | - | - | 0.29 |

| H (unclassified) | - | - | - | - | 0.17 | 4 | 0.17 |

| Cam 370 | - | - | 1.00 | 9 | - | - | 1.00 |

| Total | 0.76 | 10.57 | 4.22 | 15.55 | |||

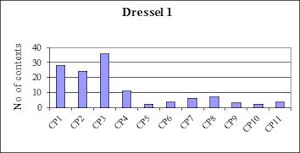

As quantified by EVE, ledge-rimmed jars were clearly the most prolific form, and very likely candidates for firing in kiln 1618. Beakers are not well represented here and, like the Cam 370 flagon, are possibly not products of these kilns. Even assuming that all of these forms were produced here, the range is very narrow. The pottery kiln at Ivy Chimneys, Witham, yielded 9.9kg of kiln products, with seventeen separate vessel forms represented (Turner-Walker and Wallace 1999, 170). From kilns 1223 and 1618, and stoke-hole 1589, sandy grey ware alone weighed almost 15kg, yet only a maximum of seven different vessel types were produced in this fabric. The difference between volume of kiln products and range of forms is more marked at Palmer's School in Grays, where the kiln yielded over 46kg of kiln pottery and six vessel types (Rodwell 1983, 26). This situation is perhaps unsurprising. Potters responded to demand, rather than risk producing pottery that no one wanted. At Heybridge, potters produced ledge-rimmed jars simply because there was a market for them. Doubtless the shape facilitated mass production; a cut groove on top of the rim and absence of decoration meant that the form could be turned out rapidly. A high diversity of forms, then, is not necessarily indicative of a high level of output.

| Kiln 1223 | Kiln 1618 | Stoke-hole 1589 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dishes | - | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Mortaria | 8 | 43 | 34 | 85 |

| Jars | - | 34 | 21 | 55 |

| Beakers | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 |

| Flagons | - | 1 | - | 1 |

| Miscellaneous | - | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 9 | 86 | 59 | 154 |

The amounts of grey ware recovered from both Area W kilns are perhaps lower than is typical. A kiln at Ivy Chimneys yielded 13.5 EVE of kiln products (Turner-Walker and Wallace 1999, 170). Over 40 EVE were recovered from the late Roman kiln at Inworth, and the Moulsham Street kiln, Chelmsford, produced 28.5 EVE (Going 1987, 74-84). These are similar in size to both kiln 1223 and 1618, yet the Elms Farm kilns yielded a little under 10 EVE. Again, that the size of the assemblage from the kilns is small may have less to do with the volume of actual production and more to do with volume of waste generated and the manner of disposal of such waste. The assemblage found within the kilns may represent the final dumping of pottery waste, a store of seconds or the last batch of unsold pottery, putting the kilns firmly out of use. Waste produced at each previous firing may well have been discarded away from the immediate environment of the kilns themselves, although no waster dumps were discerned in their wider vicinity.

Like grey ware, the range of buff ware mortarium forms is restricted, although there are subtle variations of shape. Hammerhead-rimmed D11 mortaria clearly predominate in this fabric and, in terms of vessel count, are more numerous than ledge-rimmed jars. Most examples of both mortarium types were built into the structure of kiln 1618. These mortaria were almost certainly locally produced (see Mortaria stamps). Like kiln 1618, pottery was inserted into the original structure of a kiln at Ellingham in Norfolk (Hartley and Gurney 1997). Both kilns show no obvious signs of repair. Hartley (1973, 143) suggests that this technique reduced the risk of kiln fracture upon initial firing. While the mortarium kiln at Ellingham, Norfolk, is 1.8m in diameter (Gurney and Rogerson 1997, 2), and that its capacity perhaps suited the wide design of its products, mortaria did not necessarily require large kilns. Mortaria were among the chief products from Colchester, yet were fired in kiln chambers sometimes only 1m across (Hull 1963, 158, 168). A high dome, rather than a wide chamber, facilitated the high temperatures required to fire the form. As both kiln 1223 and 1618 were 1.4m across, it remains feasible that mortaria could have been fired in either.

Wherever mortaria were fired, the high number of vessels in stoke-hole 1589 suggests that the kiln or kilns that produced them continued to do so after some of their products were used to construct kiln 1618. The number of vessels in 1223 is comparatively low. If mortaria were fired in this kiln, the chamber was infilled soon after it fell out of use, providing little opportunity for waste material to accumulate.

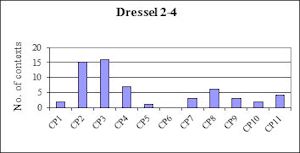

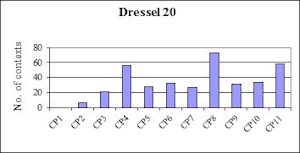

Kiln 1223 was probably built during the late 2nd century. Kiln 1618 was constructed in the late 2nd or early 3rd century AD and abandoned during the early 3rd century AD. The grey ware products in 1618 are not by themselves closely datable; ledge-rimmed jars date from the 2nd century at Chelmsford (Going 1987, 23), and production of the form up to the mid-3rd century AD is attested at Witham (Turner-Walker and Wallace 1999, 170). The forms G24 and G25 have wider date ranges, continuing into the 4th century AD at Colchester (Bidwell and Croom 1999, 479). Significantly, the G5 jar was the commonest jar form at Heybridge during Ceramic Phases 7-8 (AD 170-260).

The date of construction is best provided by the mortaria built into the structure of kiln 1618. Generally, hammerhead-rimmed D11 mortaria date to the second half of the 2nd century AD at Chelmsford and Colchester, continuing at both sites into the 3rd century AD (Going 1987, 21). K. Hartley places the production of the stamped mortaria from the kilns to the early part of the date range, AD 170-190 (see Mortaria stamps). However, construction of 1618 could be later, since unstamped mortaria were manufactured beyond this date. Early 3rd-century use is supported by the presence of folded H35 beakers and absence from the kilns of any pottery dating exclusively after this time.

The archaeomagnetic date range of AD 90-210 for the last firing of 1618 is too wide to be of any real value, but it nevertheless fits with early 3rd-century abandonment. In the absence of strong pottery dating, the archaeomagnetic date of AD 140-170 for 1223 is of greater use. Taken together, the dating evidence suggests that 1223 was abandoned before 1618, which may have been functioning into the 3rd century. Kiln 1223 may even have been built first, with 1618 being its replacement. However, 1223 remained open after disuse and continued to accumulate material until both kilns were effectively sealed. Both yielded very small amounts of non-kiln products, largely restricted to abraded body sherds, and including Nene Valley colour-coated and Hadham oxidised wares. Final closure of the entire complex is therefore likely to have occurred during the first half of the 3rd century.

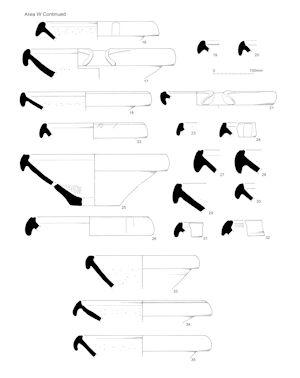

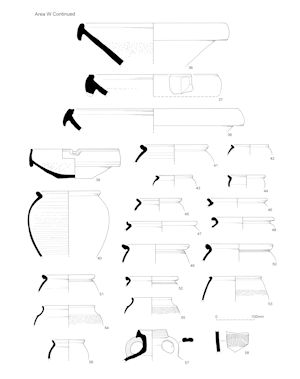

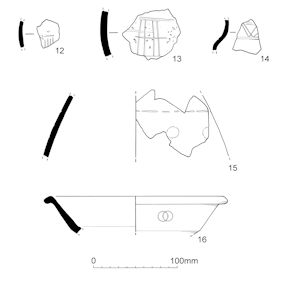

Kiln 14858 (Group 714) yielded 10,654g of pottery. Eighty-six per cent of this was spalled and overfired and has been identified as waste products. This waste material was present in three fabrics; black-surfaced ware, sandy grey ware and fine grey ware, of which sandy grey ware formed the largest proportion. Large quantities of waste pottery were also recovered from three nearby pits; 14655, 14744 and 14809. Since fabric, form and date of the pottery in these features were identical to waste pottery recovered from the kiln, it has been assumed that the source of all this material is the same. By weight, pit 14655 yielded over half of the total amount of kiln waste. Pit 14809 yielded the least, just 4% of the total.

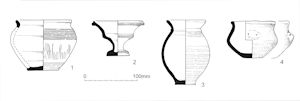

A limited range of forms was produced. Oval-bodied jars with undercut rims and plain-rimmed dishes predominated, but bead-and-flanged dishes, wide-mouthed bowl-jars, and bifid-rimmed jars were also manufactured. Notably, only bowl-jars and dishes were made in fine grey ware. The coarser black-surfaced and sandy grey ware fabrics were reserved for jars.

This moderately hard fabric has very dark grey to black (10YR 3/1) surfaces, red-brown (5YR 4/4) margins, and light to dark grey (10YR 6/1 to 4/1) core. Moderate white and red crushed flints, less than 3mm long, protrude through the surfaces. Inclusions of frequent tiny quartz grains; larger and sparser angular white and clear grains are visible macroscopically. Totals are 3030g from kiln 14858, 7226g from pit 14655, 1060g from pit 14744, and 462g from pit 14809.

Forms: Dishes B1 B6, bowl-jar E5, jar G24

The fabric has dark grey (10YR 4/1) surfaces, with some lighter grey (10YR 4/2) patches. The core is usually red-brown (5YR 4/2); some examples are grey throughout. Inclusions are as for BSW, except that surfaces and core are flintier. Totals are 5720g from kiln 14858, 7005g from pit 14655, 2225g from pit 14744, and 758g from pit 14809.

Forms: Dishes B1 B6, bowl-jar E5, jars G24 G42 G (bifid rim)

Smooth surfaces, sometimes burnished. Surface colour as GRS; some very dark grey, almost black surface patches, presumably the result of firing. Light grey (10YR 6/1 to 5/1) core. Inclusions as for GRS. Totals are 428g from kiln 14858, 905g from pit 14655, 100g from pit 14744, and 18g from pit 14809.

Forms: Dishes B1 B6, bowl-jar E5

B1

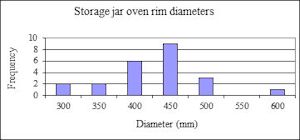

Plain-rimmed dish with flat base. Rim is slightly bulbous and inturned. Burnishing in narrow bands on external and internal surfaces. Diameters range from 120 to 240mm. Gillam (1976, 76) suggested that this type was possibly used as a lid in conjunction with the flanged B6, forming a set akin to a casserole. The frequent appearance of both forms within kiln 14858 and associated pits, and the fact that diameters of both forms seemingly correlate lends some credence to this suggestion. Indeed, some of the more complete B1 dishes fitted the B6 dishes rather well.

B6

Bead-and-flanged dish with tapered, slightly convex sides and flat base, corresponding closely to Chelmsford form B6.2. There is variation in the shape of the flange, which is usually downturned, and can be fat and short or thin and extended. The flange is less frequently upturned. In many instances, the flange had broken off, probably during firing. Burnished bands decorate most vessels, never completely covering the external and internal surfaces. Diameter range 180 to 240mm.

E5

Round-bodied, wide-mouthed vessel with bead rim. Products correspond to Chelmsford forms E5.3 and E5.4. The former has a typical diameter of 140mm; the latter is larger with a diameter range of 200 to 240mm. Decoration is restricted to shoulder grooves and a single burnished wavy line, though this is by no means present on all vessels. The form was commonly produced elsewhere, including Moulsham Street, Chelmsford (Going 1987, fig. 35.7-9), Ivy Chimneys, Witham (Turner-Walker and Wallace 1999, fig. 113.8-9), and Mucking (Rodwell 1973, type K). This vessel type was also present in the Crescent Road kiln 'waste assemblage' (Wickenden 1986, fig. 17.39-40).

G24

Jar with oval body, undercut bead-rim, and slightly stepped shoulders. Diameter range 140-260mm. The product closely resembles Chelmsford form G24.2. There are no decorative details, but products are typically coarser and flintier than dishes or bowl-jars, and no example appears in fine grey ware. The form was produced at Ivy Chimneys, Witham (Turner-Walker and Wallace 1999, fig. 113.16), Moulsham Street, Chelmsford (Going 1987, fig. 35.10), Orsett (Rodwell 1974, fig. 8.61), and Mucking (Jones and Rodwell 1973, type J), among other sites.

G42

Short-necked 'storage jar' with wide, rounded body and thick bead rim. Examples have 'wheat-ear' stabbed shoulder decoration, and diameters of 200 and 240mm. Exact parallels are lacking, but similar vessels were produced at, for example, Mucking (Rodwell 1973, type S), Moulsham Street, Chelmsford (Going 1987, fig. 35.18) and Inworth (Going 1987, fig. 41.23).

G (bifid rim)

Jar with bifid rim and short neck. Though non-joining, the two rim sherds from separate pits are likely to form part of a single vessel. Despite this very low incidence, local production is very likely. Its fabric is identical to sandy grey ware recovered from kiln 14858, the rim sherds are spalled, and there are no close parallels.

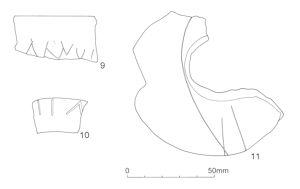

| Number | Context | Feature | Fabric code | Form |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14564 | 14655 | BSW | Dish B1 |

| 2 | 14564 | 14655 | BSW | Dish B1 with post-firing graffito |

| 3 | 14743 | 14744 | GRS | Dish B1 |

| 4 | 14564 | 14655 | GRF | Dish B6 |

| 5 | 14564 | 14655 | GRF | Dish B6 |

| 6 | 14564 | 14655 | BSW | Dish B6 |

| 7 | 14564 | 14655 | BSW | Dish B6 |

| 8 | 14564 | 14655 | GRF | Dish B6 |

| 9 | 14564 | 14655 | GRS | Bowl-jar E5.4 |

| 10 | 14564 | 14655 | GRS | Bowl-jar E5.4 |

| 11 | 14743 | 14744 | GRS | Bowl-jar E5.3 |

| 12 | 14564 | 14655 | GRS | Jar G24.2 |

| 13 | 14743 | 14744 | GRS | Jar G24.2 |

| 14 | 14743 | 14744 | GRS | Jar G24.2 |

| 15 | 14564 | 14655 | GRS | Jar G42 |

| 16 | 14564 | 14655 | GRS | Jar with bifid rim |

| Kiln 14858 | Pit 14655 | Pit 14744 | Pit 14809 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVE | % EVE | EVE | % EVE | EVE | % EVE | EVE | % EVE | Total | |

| B1 | 0.61 | 19 | 2.03 | 31 | 1.53 | 33 | 0.05 | 4 | 4.22 |

| B6 | 0.57 | 18 | 1.82 | 27 | 1.12 | 24 | 0.45 | 38 | 3.96 |

| E5 | 0.28 | 9 | 0.76 | 11 | 0.82 | 17 | 0.34 | 29 | 2.20 |

| G24 | 1.70 | 54 | 1.70 | 26 | 0.78 | 16 | 0.34 | 29 | 4.52 |

| G42 | - | - | 0.11 | 2 | 0.28 | 6 | - | - | 0.39 |

| G (bifid) | - | - | 0.22 | 3 | 0.17 | 4 | - | - | 0.39 |

| Total | 3.16 | 6.64 | 4.70 | 1.18 | 15.68 | ||||

| Kiln 14858 | Pit 14655 | Pit 14744 | Pit 14809 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dishes | 10 | 37 | 29 | 3 | 79 |

| Bowl-jars | 2 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 16 |

| Jars | 11 | 12 | 7 | 1 | 31 |

| Total | 23 | 54 | 43 | 6 | 126 |

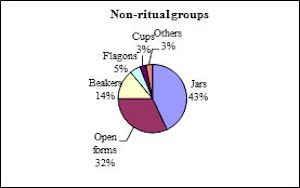

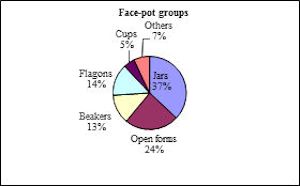

Measured by EVE, dishes were the most prolific class, followed by jars and then bowl-jars. The order of vessel frequency is retained when the minimum vessel number is calculated. It can be seen that, of the dishes, the B1 type is slightly more numerous than the B6, and the G24 jar far outnumbers other jar forms. Notably, G24 jars were the most frequently produced form at the Moulsham Street kilns, Chelmsford (Going 1987, 74), followed by B1 and then B6 dishes. As at Orsett (Cheer 1998, 99) and Chelmsford, B1-type dishes are better represented than B6-type dishes, although the difference at Heybridge is perhaps negligible. There is no obvious reason for this difference, except to suggest that plain-rimmed dishes were simply in greater demand than bead-and-flanged dishes. It might also be suggested that B6 dishes were always made to pair B1 dishes, but additional B1 dishes were produced for lone use. Bowl-jars never rivalled jars and dishes in terms of the quantity of production. This appears to be the case, not only here, but also at Chelmsford (Going 1987, 74) and Mucking (Rodwell 1973, 36-7). The relative popularity of all these products must derive from functional differences. Jars and dishes perhaps had multiple functions, for example, cooking, storage and tableware. Consequently, more vessels were required to fulfil these roles, and replace vessels that broke through constant use. Bowl-jars possibly served singular and less intense functions, perhaps confined to the dinner table, and therefore lasted longer.

This functional division may also explain why fine grey ware was the least common of the three kiln fabrics (Table 26).

| Fabric | EVE | Weight (g) |

|---|---|---|

| GRS | 9.92 | 15708 |

| BSW | 6.06 | 11778 |

| GRF | 2.79 | 1451 |

The amount of kiln waste recovered from kiln 14858 was very low compared to the 40 EVE, or so, collected from the kilns at Moulsham Street, Chelmsford and 20 EVE from Inworth. The overall quantity is, of course, higher, but the figure remains comparatively low. Indeed, rim circumferences were rarely more than half-complete. As in Area W, the pottery recovered here, and particularly from the kiln, seems to represent little more than the 'sweepings-up' of already broken and discarded waste material.

The similarities between the waste pottery collected from kiln 14858 and its associated pits and the pottery produced at Inworth and Chelmsford merit comment. These production sites can be linked on the basis of the crushed flint temper that the potters used, and more or less identical forms, suggesting a single potting tradition. While itinerant potters might link two manufacturing sites of comparable date, it is harder to apply to a tradition lasting almost 100 years. The mechanisms that introduced flint-tempered pottery are unknown, though strong cultural and economic links within the region doubtless had their parts to play.

These products, presumably fired in kiln 14858, were manufactured sometime during the late 3rd century or the first half of the 4th century AD. Production probably ceased before the mid-4th century AD. These assertions are made on the basis of the fabrics and range of forms produced. The sandy grey and black-surfaced fabrics represented here were tempered with crushed flint, and could be regarded as forming part of the tradition of flint-tempered fabrics in Essex. Flint-tempered pottery was recovered from the Moulsham Street kiln in Chelmsford (Going 1987, 74-8), and the much flintier Rettendon-type fabric produced at Inworth (Going 1987, 83), Sandon (Drury 1976), and Rettendon itself (Tildesley 1971). Going (1987, 89) provided a late 3rd to mid-4th century AD date for the production of these fabrics, which he viewed as forming an interconnected workshop industry.

Some of these sites also offer parallels to the range of forms represented at Elms Farm. Potters working at the Moulsham Street kiln site included all six forms, except the bifid-rimmed jar, in their repertoire. A late 3rd or 4th century kiln assemblage from Orsett (Rodwell 1974, 32) included B1 and B6 dishes, E5 bowl-jars and G24 jars. The parallels from Inworth are less exact, though most of the six vessel types are broadly represented. The B6 dish is perhaps the key to providing a date. While B1, E5 and G24 jars were produced prior to the late 3rd century, B6 dishes were only made after c. AD 260 (Going 1987, 15). Notably, the form is absent from the kiln assemblage from Ivy Chimneys, which dates no later than the mid-3rd century AD (Turner-Walker and Wallace 1999, 170).

While a late 3rd century, or later, date for pottery production is reasonably certain, the date of abandonment is less clear. Pit 14655 produced typically later 4th century pottery, including late shell-tempered ware, and a coin of Valentinian II (AD 388-392), but these could well be intrusive. The pottery, particularly, is very abraded. That production ceased before the mid-4th century is suggested more strongly by the presence in the same feature of a G24 jar in Rettendon ware and a Nene Valley colour-coated bowl with painted decoration from pit 14744. The latter is of a type that declined after the mid-4th century (Perrin 1999, 104). Both imply that waste products were deposited any time up to, but no later than, the mid-4th century AD. Notably, the kiln itself yielded nothing of exclusive mid-4th century date or later.

The archaeomagnetic dating is inconclusive, but does not necessarily contradict the pottery dating. Two dates for the last firing of the kiln are offered; AD 150-210 and AD 270-400.

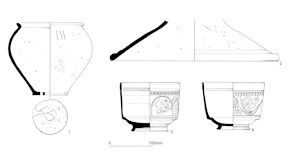

Kiln 10906 (Group 672) yielded 6346g of pottery, none of which could be positively identified as waste products. There were, however, a number of larger body sherds and diagnostic fine grey ware rim sherds in good condition among the small and abraded sherds, and are feasibly kiln products for these reasons. A total of 2113g was recovered from second kiln 11423 (Group 693). Again, no products were identified by form, although the kiln contained groups of spalled or heat-damaged sandy grey ware sherds. This small collection, amounting to 240g or 11% of the total, has been tentatively identified as kiln waste.

A micaceous fabric with dark grey (5Y 5/1 to 4/1) surfaces and darker grey (2.5Y 4/0) or grey brown (2.5Y 4/2) core. Fine clay matrix with well-sorted white quartz, resulting in a speckled appearance. Occasional larger quartz grains, visible macroscopically. Surfaces have patchy burnish.

Forms: Dish B2, bowl-jar E2, jar G (pedestal base)

A micaceous and slightly gritty fabric. Surface colours vary in shades of grey (10YR 6/1 to 4/1). Inclusions of white and clear quartz grains, and very occasional flint. No forms identified.

Three vessel types, all in fine grey ware, were identified as possible products of kiln 10906; a shallow bead-rimmed dish (B2), a ledge-rimmed neckless globular jar (E2), and a jar with a frilled pedestal base resembling Cam 207. Single examples of each were recovered.

Whether fired in the kiln or not, they suggest that the structure was abandoned probably in the first half of the 3rd century AD. Pedestalled jars were manufactured in Essex during this time, for example at Grays (Rodwell 1983, 34) and Mucking (Pollard 1983, 135), while the E2 bowl-jar dates from the late 2nd century onwards (Going 1987, 21). The dish provides a mid-3rd century ceiling. This form was produced up to or a little beyond this date at Ivy Chimneys (Turner-Walker and Wallace 1999, 170) and Orsett (Cheer 1998, 101), but was absent from late 3rd century-plus kiln assemblages at Chelmsford or Inworth (Going 1987, 78, 88). Much of the pottery recovered from the kiln deposits more strongly suggests early to mid-3rd century abandonment, and includes an H35 folded beaker and a D3 mortarium.

Kiln 11423 could well have been broadly contemporary with 10906. Pottery, including BB2, recovered from packing deposits date construction to the second half of the 2nd century AD, while bead-rimmed dishes from disuse deposits suggest that the kiln was abandoned by the mid-3rd century AD. This accords well with the archaeomagnetic date of AD 225-250 for its last firing.

A combination of stratigraphy, artefactual evidence and archaeomagnetic dating fixes the maximum lifespans of the kilns and places them within a chronological sequence. However, establishing the actual length of time that the kilns were in use, the scale of production and the organisation of the work are altogether more challenging and are beset with problems of interpretation, but it is these answers that provide insights into the part that pottery production played in the economy of Heybridge and the daily lives of its inhabitants.

A sense of scale is achieved by estimating the kiln output. Using the assumed wastage rate of 5-10% (Cheer 1998, 99), the approximate total weights of products from the kilns in Areas W, L and N is 300 to 600kg, 290 to 580kg, and 2.5 to 3kg. respectively.

| Wastage rate at 5% (g) | Wastage rate at 10% (g) | |

|---|---|---|

| Area L | 578740 | 289370 |

| Area W (BUFM) | 315620 | 157810 |

| Area W (GRS) | 297860 | 148930 |

| Area N | 4800 | 2400 |

Together, these are well below the total attained at Orsett 'Cock', but still must be regarded as conservative estimates. As Cheer noted (1998, 99), the total quantity of waste pottery available from a site is an unknown factor. In any case, these figures are based on the total amount of recovered kiln products, which potentially represent any number of firings. Clearly, the output from a single firing cannot be estimated reliably, as the resultant waste material cannot be isolated. While a greater volume of kiln products were recovered from Orsett, the Heybridge kilns may have had fewer firings, but produced more pottery.

Kiln size, too, does not necessarily reflect cumulative output, though has some bearing on the maximum loads held by each kiln in a single firing. All but one of the Elms Farm kilns measured between 1.3 and 1.5m in diameter. This compares favourably to some Mucking (Jones and Rodwell 1973, fig. 2) and Orsett 'Cock' kilns (G.A. Carter 1998, 62-70), which were between 1.0 and 1.6m wide. These yielded far larger quantities and more diverse ranges of pottery than was present at Heybridge, though all these kilns may have had similar capacities. However, without the evidence of the superstructure, the exact capacities remain unknown. Measurements, listed in the archive, for twenty-four regional kilns have provided a figure of 1.3m for their average diameter.

Far more problematic is linking the pottery to the use of the kilns. While spoiled pottery can be recognised by its condition (e.g. overfired, misshapen or blown), it cannot be ascertained whether pottery recovered from the backfills of kilns were actually fired in those kilns. The presence of sherds that are clearly not local, such as Nene Valley and Hadham wares serves to remind us that the kilns, once abandoned, are, to some extent, merely ordinary receptacles for rubbish. In addition, the waste pottery recovered from a kiln is more likely to relate to its last firing, rather than reflect its entire use. While quantification of kiln products takes us towards an estimate of the scale of pottery production, it cannot so usefully indicate the life span of any kiln or the number of firings undertaken.

Instead, the life span of a kiln may be better established by identifying rebuild and repair. Taking Fulford's suggestion of one rebuild per season (1975a, 22), the absence of visible signs of repair or rebuild in all but two of the kilns suggests that they each had a life-span of no more than a single potting season. Kiln 11423 showed at least one episode of repair, suggesting continued use into a second season. The mortaria built into kiln 1618 may also be evidence of repair. The flue walls of kiln 11423 in Area N had also been repaired at least once. Identifying repair, however, is problematic, as it becomes visible only when parts of the previous structure remain extant. The original structure would leave little trace if it were replaced in one go. In addition, parts of the structure may have needed repair on a regular basis, so that, by the end of the first season, the kiln had already undergone structural changes.

A single or short period of use may help to explain the somewhat limited repertoire suggested by the Area W and L waste pottery. Potters were likely to have set up a kiln and produced pottery knowing that they would be able to sell it. What was produced during the initial period of use perhaps represented the immediate satisfaction of the market. Expansion of the repertoire came when potters became more familiar with the demands of the market or felt confident enough to introduce new shapes. Both suggest an element of longer-term production and, in the case of the latter, financial security. A narrow range of forms, then, does not necessarily suggest small-scale production, but rather an intensive and short production period.

On the current evidence, then, pottery was manufactured at Heybridge on a seemingly intermittent basis between the late 2nd and first half of the 4th century (Figure 321). However, given the view that the kilns could have been functioning for longer, the possibility that production was continuous between these dates and beyond cannot be dismissed. In addition, it is by no means unreasonable to suggest that there remain other, as yet undiscovered, kilns at Heybridge located away from the settlement and nearer to abundant fuel sources, such as woodland.

The concept of the itinerant potter is one that provides a convenient (if unconvincing) explanation for sporadic production. A potter could relocate, set up a kiln and satisfy the immediate demand before moving on. But as long as pottery was used, there was a demand for it. An itinerant potter would need to return to a location on a regular basis, perhaps every year. Competition between potters might complicate matters, with rival potters also setting up kilns. If anything, given this model, we should expect makers' marks on coarse pottery in order to differentiate products, and the presence of many more kilns. The effort required finding suitable locations with good clay and fuel sources, setting up a kiln and preparing the clay before actually making pots should not be underestimated. Once the infrastructure was in place, the potter might well be reluctant to shut-up shop, move on and start afresh. It should be noted that the kilns in Areas L and N appear to be located in domestic plots or small-holdings and were perhaps operated by the occupants/owners of these plots. An alternative model, therefore, proposes that a potter was permanently resident in the settlement, operating his kiln on a seasonal basis or during the time that was available for potting. The potter might supply other settlements by transporting the goods himself or using the services of a middleman. Opinion now tends to favour this model, based as it is on ethnographic parallels (Cheer 1998, 101). The close proximity of some kilns to domestic plots also supports the model, although such locations may be the exception rather than the rule.

What constitutes the 'potting season' also deserves some attention. Presumably, if potters were farmers engaging in agriculture as well as tending livestock, a potting season was equal to the number of months spent away from farming-related activities. Periods available for potting extended across the year, but these may have been short. Heated drying sheds would certainly be required for winter and spring production, as these months could scarcely have been advantageous to the potter, who would not be able to dry pots in wet and cold weather or easily collect dry fuel. Seasonal manufacture, predominantly during the drier and warmer months, provides the best explanation for the evidence at Elms Farm. It implies production of a surplus; potters must produce enough vessels to meet an all-year round demand. Furthermore, this suggests intensive production, which would not necessarily benefit from the uncertainties of the market, and perhaps even discourage potters from testing the market and extending their repertoires.

In summary, despite the ambiguities of the evidence, the kilns at Heybridge were probably in service for a short time, perhaps for one or two seasons only. While the impact of these kilns was restricted, pottery production is likely to have played an integral part in the local economy throughout the Late Iron Age and Roman periods. It has been argued elsewhere that most coarse wares had a probable local origin (Atkinson and Preston 2015), and the absence of kilns does not necessarily mean that no local production took place. It is evident that a single potter, even working for part of the year only, could have supplied the settlement at Heybridge, which perhaps had a population of no more than 400 people (probably nearer 200) at any one time. Greene (1993, 44) has suggested that four potters working for a period of ten years supplied all the pottery required for a legionary fortress in which the population at any given time would have certainly numbered in the thousands. Assuming a working life of 20 to 25 years, over a period of 150 years - roughly the period that the kiln evidence encompasses - we should expect just six potters to have been active (or eighteen potters to cover the entire Late Iron Age and Roman occupation). Assuming that the best place to locate a kiln is in a sheltered place with access to fuel and water, it is unlikely that excavation of a settlement itself, rather than its hinterland, would reveal many kilns. Indeed, like Area W kilns 1223 and 1618, further structures were probably located just beyond the settlement edge.

The potters themselves, perhaps settlement residents, were probably 'part-time', undertaking the work during slack periods of the farming calendar. If so, local production cannot properly be termed an industry. Unlike pottery manufacture at Heybridge, large production centres, such as those in the Nene Valley and at Colchester, were organised on more industrial lines, implying permanent production, wider distribution, and a full-time 'professional' workforce responding to and influencing the market.

Cite this as: Biddulph, E. and Compton, J. 2015 Vessel function and use, in M. Atkinson and S.J. Preston Heybridge: A Late Iron Age and Roman Settlement, Excavations at Elms Farm 1993-5, Internet Archaeology 40. http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.40.1.biddulph2

Beyond issues of chronology and supply, the extensive pottery assemblage has great potential for the study of its functional aspects, providing insights into the lifestyles of the people, and their varied use of, and attitudes towards, ceramic vessels. Pottery was clearly a very significant and versatile resource, evidenced by its sheer amount and variety. The studies presented below provide an idea of the multifarious applications of pottery in daily life.

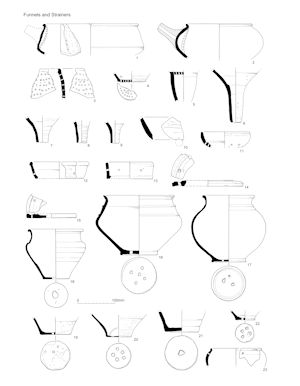

Changes in vessel shapes reflect changing uses of pottery. In some cases, changes in vessel function, and therefore the daily habits of pottery users, can be traced through time. This is exemplified here by the study of dishes and platters. We should nevertheless be wary of assigning functions to vessels on the simplistic criterion of shape alone, and acknowledge that particular types may have had varied uses. The studies of use-wear on samian vessels and of storage jar ovens clearly demonstrate this.

The functions of some vessel types tend to be fixed in the literature and the large dataset allowed many conservative notions and labels to be challenged. Amphoras are a familiar aspect of site assemblages, but rarely considered in terms of their continuing use beyond the role as transport containers. Perforated vessels are dismissed as cheese presses or colanders, or, more recently, as being 'ritually killed'. Closer analysis reveals a far wider variety of uses. Pots may have been invested with symbolism - graffiti may have been added, the form itself might have been special (e.g. face vessels), or the vessels were deliberately placed within significant deposits. Such treatment reflects attitudes towards vessels, which, in some cases, were likely to pertain to religious and sacred practices. Further discussion of these aspects is made in the sections relating to burials and structured deposits (both in and outside the temple precinct).

The studies presented focus on aspects that provided the clearest results. The very large ceramic assemblage, however, offers the potential for a wider range of studies that could not be attempted in the time available, such as investigating associations between vessel types and other artefacts. Other aspects were considered, but dismissed due to poor-quality data and lack of clear patterning; for instance, defining the relationship between lids and lid-seated jars. In contrast, some of the successful studies opened up further avenues of inquiry that could not be pursued owing to project constraints. Subsequent work using correspondence analysis on parts of the pottery data (Biddulph 2005; Pitts 2005) has highlighted the potential for further study, especially with regard to associations between vessel classes and feature types. The pottery resource provides many more possibilities for future research.

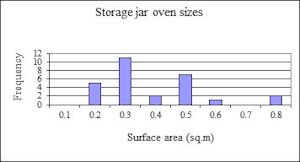

The starting point for this study was Going's statement, with regard to Chelmsford, that, 'later Roman dish forms (incipient flange-rimmed, fully flange-rimmed and deep plain-rimmed dishes) do not fulfil the same function as platters, which as a class are quite absent' (1987, 13). This idea derives from Going's observation that 'most dish forms, particularly from late Roman contexts, are comparatively small and deep', as compared to platters and earlier dishes (Going 1987, 14). The extensive pottery assemblage from Elms Farm allows us to test two basic ideas. First, that dishes and platters did not serve quite the same functions, and second, that later Roman dishes (that is, those dated mid-3rd century onwards), became smaller and deeper, probably as a result of changes in function. Samian data were excluded from the study, mainly because of its relatively short date span at Elms Farm.

| Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Phase 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean diameter (mm) | 300 | 275 | 316 |

| S.D. | 55 | 69 | - |

| Number of examples | 18 | 16 | 1 |

Differences between platters and dishes were examined using the variables of diameter and depth. Tables 28 and 29 give the mean diameters of platters over time, based on a sample of 175 platters. Just one continental platter record belonged to Ceramic Phase 1, and so was amalgamated with Phase 2. Similarly, the single Ceramic Phase 6 local platter record was amalgamated with Phase 5. The results suggest that continental platters were consistently wider than locally produced types. The mean diameter of local platters was remarkably consistent through time, although it is significant that in Phase 5, when local platters were narrowest, the standard deviation was low. There is a narrower range of diameters at this time, suggesting that the size of platters was further standardised.

| Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Phase 4 | Phase 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean diameter (mm) | 225 | 225 | 226 | 192 |

| S.D. | 50 | 49 | 54 | 25 |

| Number of examples | 21 | 60 | 33 | 27 |

Next, the depths of sixty-eight platters were measured (using archive drawings) and the observations separated into ceramic phases. Means and standard deviations were calculated (Table 30).

| Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Phase 4 | Phase 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean depth (mm) | 22.6 | 24.7 | 25 | 34.6 |

| S.D. | 7.8 | 6.0 | 6.3 | 8.0 |

| Number of examples | 23 | 21 | 11 | 13 |

It would appear, then, that platters became deeper over time. To ensure that one or two extreme values, or outliers, did not cause the difference between Phase 4 and 5 means and the relatively large Phase 5 standard deviation, two outliers (a 10mm deep platter from Phase 4 and a 49mm deep platter from Phase 5) were excluded. If anything, this confirmed the apparent difference. The Ceramic Phase 4 mean rose to 26.5mm, while the Phase 5 mean stayed firm at 34.6mm and this standard deviation was reduced to 5.8mm.

Comparing the diameters of continental platters and grog-tempered platters, it is apparent that the imported platters are wider than locally produced varieties, and it is this difference that accounts for the large means in Ceramic Phases 2 and 3. The overall mean diameter of continental platters from the original sample of 175 vessels is 289mm; that of grog-tempered varieties is 217mm. It is also clear that grog-tempered platters were not full copies of continental prototypes, certainly in terms of size (Table 31).

| Continental prototype | Grog-tempered copy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Form | Mean diameter (mm) | Form | Mean diameter (mm) |

| Cam 1 | 286 | Cam 21 | 228 |

| Cam 2 | 283 | Cam 22 | 241 |

While local potters copied some elements of shape, the difference in diameter suggests that they may have been unable, or perhaps unwilling, to reproduce full-sized platters. The skills and equipment required to produce fine, wide, shallow platters were perhaps not sufficiently advanced during the Late Iron Age in southern Britain. The production of comparatively small vessels, while approaching the right shape, may have been the limit of the technical abilities of local potters. Rigby noted that potters local to Verulamium produced versions of imported platters, but manufacturing techniques meant that production was comparatively small scale and the forms less standardised than their continental prototypes (1989, 152). The diameters of the local platters from Heybridge suggest that production was just as standardised, at least in terms of size.

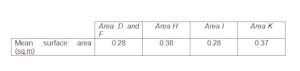

To facilitate comparison dishes were examined, again using the variables of diameter and depth. It should be noted that not all of the 825 available vessels were from closely dated contexts. In such cases, the ceramic phase nearest to the middle of the date range was selected. Thus, a dish from a context dated mid-2nd to mid-3rd century was assigned to Phase 7 (AD 270-310). The mean diameter and standard deviation for each phase was calculated (Table 32).

| Phase 4 | Phase 5 | Phase 6 | Phase 7 | Phase 8 | Phase 9 | Phase 10 | Phase 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean diameter (mm) | 211 | 200 | 200 | 214 | 226 | 215 | 219 | 196 |

| S.D. | 43 | 34 | 51 | 44 | 47 | 45 | 50 | 40 |

| Number of examples | 7 | 21 | 34 | 139 | 164 | 156 | 75 | 229 |

While both the means and diameter ranges vary to some extent, the figures do not suggest an overall and sustained change in vessel diameters. To investigate whether dishes became deeper over time, all dishes with a complete profile were measured (the internal height of the vessel from the point where the vessel wall meets the base to the rim). There were no records assigned to Ceramic Phase 4, while Phases 5 and 6 contained just three and five observations respectively and so were amalgamated. The means and standard deviations were calculated (Table 33).

| Phase 5/6 | Phase 7 | Phase 8 | Phase 9 | Phase 10 | Phase 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean depth (mm) | 43.8 | 42.0 | 38.4 | 45.0 | 49.5 | 42.6 |

| S.D. | 9.9 | 8.5 | 13.7 | 17.6 | 18.0 | 13.9 |

| Number of examples | 8 | 21 | 18 | 21 | 17 | 28 |

It would appear that dishes were made deeper in Ceramic Phases 9 and 10 (later 3rd to mid-4th century), occurring at a time when flanged dishes had replaced bead-rimmed dishes at Heybridge (see Pottery supply). However, it should be noted that the standard deviation is highest also for these phases. In other words, the differences between the extreme values and the arithmetic mean are at their largest. As just one or two outliers may cause such differences, the extreme values in Phases 9 and 10 (one in each) were excluded. The mean and standard deviation for Ceramic Phase 9, at 42.8mm and 14.6mm respectively, thus resembled those for Phases 5-8. Phase 10, however, was largely unchanged. Such an apparent difference is likely to be statistically insignificant. Admittedly, there was a greater occurrence of deep dishes (that is, over 60mm deep) in Ceramic Phase 10 than in any other, but the majority of dishes in this phase were, in fact, under 40mm deep. There is, therefore, no conclusive evidence to suggest that dishes became smaller or deeper over time.

In summary, local platters, while becoming deeper over time, were reasonably similar to dishes in diameter. It is a commonly held assumption that size is one determinant of how a vessel might have been used; others include context, practicalities, and individualistic interpretation (Willis 1998, 113). Considering these, a model may be proposed; large vessels enjoyed communal use, while smaller vessels were more suitable for individual portions. At their widest, then, platters (mainly continental varieties) were probably placed in the centre of the dinner table, from which the participants of the meal took, or were served, their food. Over time, diners tended to eat from 'individual'-sized platters, with food perhaps being served from large bowls, such as the wide-mouthed C28-C33 types, and even samian bowl forms (see samian use-wear). The bowl was a relatively minor form during the Late Iron Age (Ceramic Phases 1-3), but became as common an open form at Heybridge as platters during the Early Roman period (Phases 4 and 5) (see Pottery supply). It is speculation as to why platters became deeper, but may perhaps indicate a reversion to native-style foods.

As a vessel class, the bowl declined in popularity from the mid-2nd century (Ceramic Phase 6) to be seemingly replaced by deep dishes, particularly the B4 bead-rimmed dish. While it is clear that dishes did not radically alter in depth over time, the large standard deviations reveal that there is a spread of values in each phase. Put simply, potters made both shallow and deep dishes throughout the Roman period. It should be noted, incidentally, that there was no 'standard' shallow or deep measurement - observations in each phase do not fall neatly into two distinct groupings - and some dishes might have been used equally for both eating and serving.

Generally, local platters had similar diameters to dishes of all periods, but were shallower, though the difference in millimetres is perhaps negligible in practical terms. Thus, the evidence suggests that platters served a similar function to dishes. The development of samian vessels appears to be analogous. Willis (1998, 113) noted that samian dishes eventually replaced samian platters, but, while shape changed, the capacities of both vessel types were similar, suggesting that there was no change to their basic functions.

The range of platters and dishes at Elms Farm perhaps allows us to trace evolving functions, beginning with the direct transference of Gallic (and ultimately Roman) uses, through to native adaptation, and concluding with dishes, and a set of functions, culturally distinct from the original uses of continental platters. Roman literature can perhaps provide an impression of these original uses of continental platters, in which it seems that social and aesthetic considerations were as important, if not more so, than practical reasons in the development of vessels. The Younger Pliny (3.1) describes a 'simple' meal of several courses. The multi-coursed dinner is alluded to in another letter (5.6). In both, the emphasis would appear to be on choice for the diner and munificence on the part of the provider. Wide, shallow, platters were ideal table vessels, in which the food was presented and admired before being served. Thus, at Heybridge, the specific and restricted social context of which continental platters were a part became devolved with the probable immediate production of platters in local wares, incorporating a more individualistic and prolific use of the form, but perpetuating continental styles of dining. These uses continued with the development of dishes.

Because dishes did not radically alter in size over time, they continued to serve the same functions until the end of the Roman period. This does not rule out the possibility that dishes acquired functions around the mid-3rd century, resulting in shape changes. The rapid typological development to which dishes were subject is critical to this argument. The dish acquired a flange by the mid-3rd century to accommodate functional changes (e.g. to support a B1 dish inverted to form a lid for cooking). By the end of the 3rd century, the incipient bead-and-flanged B5 was largely superseded by the fully bead-and-flanged B6. The mid- to late 3rd century was, then, a period in which the design of the dish was perfected to suit its new purpose. The changing assemblage composition from Ceramic Phase 8 (AD 210-260) to Ceramic Phase 11 (AD 260-410) supports this hypothesis. From the mid-3rd century, two form types, the plain-rimmed B1 and B3, became more frequent, while two new form types, the bead-and-flanged B5 and B6, were introduced. In addition, the only identifiably new jar type was a storage vessel, as opposed to a cooking vessel (see Pottery supply). Ceramic Phase 10 (AD 310-360) marks a sharp rise in the number of dishes, with the number of jars remaining steady from Phase 9. More dishes were required to meet their additional role. As if to underscore these observations, and revealing the increasing importance of dishes during this time, pottery manufacturing waste assemblages from kiln 14858, dated late 3rd to first half of the 4th century (see Pottery production above), comprise 58% dishes (both B1 and B6) by EVE, compared to 38% jars.

It is entirely possible that this new role was kitchen-based. Studying the black burnished wares from northern Britain, Gillam posited that plain-rimmed dishes were used in conjunction with flanged dishes to form 'casserole-sets' (1976, 70). Comparing the mean rim diameters of B1 and B6 dishes from Heybridge provides some statistical affirmation that these dishes, plain- and flanged-rimmed, respectively, were indeed used together. B1 dishes dated mid-3rd century onwards have an average diameter of 197mm; that of B6 dishes is 204mm. Some small difference between them is to be expected since the measurements from B6 dishes are taken from the tip of the flange on one side to that on the other. The rim diameter of the B1 dish needs only to extend beyond the bead of the B6 dish. Examples of the likely use of pairs of dishes in sets are demonstrated figuratively in Gillam (1976, fig. 6.89-91)

In this study, the development and function of platters and dishes have been examined. While there are undoubtedly size differences between the two vessel classes, it is probable that they effectively served the same functions. It is more certain that dishes did not radically alter over time, but acquired, rather than changed, functions. Future studies could examine whether flanged dishes were consistently deeper than plain-rimmed dishes during the later 3rd and 4th centuries. If so, this would link shape and size and strengthen the belief that flanged dishes were made for a specific purpose. Examination of signs of cooking, for example burning and residues, might also prove instructive.

As well as the examination of form itself, the study of use-wear upon ceramic vessels is informative as to vessel function. Colour-coated vessels provide the best evidence of use-wear. Breaks in the slip caused by abrasive processes accompanying cooking, consumption and other activities can be clearly seen. Intensive use of a vessel eventually removes the slip. Where the same regular process is applied to a vessel, a wear pattern will emerge. Identification of wear patterns is therefore crucial for assigning functions to specific vessel types. For the purpose of this study, samian vessels were examined. The range of samian vessel classes is sufficiently wide to reveal information about a variety of household settings. In contrast, other colour-coated vessels found at Elms Farm, for example those manufactured at Colchester and in the Nene Valley, mainly comprise beakers, which tend to show use-wear, if any, less clearly. However, analysis of this sort remains possible by using a wider range of products from these industries not available at Heybridge. Wear patterns were noted in too few vessels to be able to gain spatial or chronological insights. This is not to say that processes that caused the patterns were very infrequently practised at Heybridge, but rather that few vessels could be sufficiently reconstructed to identify patterns sufficiently. Practices were likely to have been more widespread than the small number of vessels studied here suggests. Perhaps the most common sort of wear to affect samian vessels was that on the underside of foot-rings and the top of rims. However, this is deemed to be incidental, as it reveals little about vessel function per se.

Two cup forms, f27 and f33, were particularly strong in wear-pattern evidence, with many examples displaying very consistent patterns. That noted on f27 cups is similar to the wear seen on bowls, see below. In Figure 340, the wear pattern can be seen to be circular, and the stamp is almost entirely worn away. A more developed pattern, probably achieved through prolonged or more intensive use, is seen in Figure 341. Here, the wear extends to the lower wall, forming an even boundary around it. Again, the base interior retains very little slip.

Form 33 cups tend to have a ring of wear at the junction of the base and wall. In Figure 342, the centre of the base can be seen to be unworn, but the base is very worn at the edge. A thin ring of slip is retained in the basal angle, but a second wear-ring is present at the bottom of the wall. Just as with f27 cups, a progression can be observed (Figure 343). Prolonged or intensive use generally results in a thicker wear-ring radiating towards the centre of the base. The corner between the base and wall, too, has become worn.

The remarkable aspect about both forms is their exclusive wear patterns. Very few f27 cups that displayed use-wear had patterns other than those described above. Similarly, f33 cups either showed no wear at all or a wear-ring at the junction of the base and wall. This suggests f33 cups were used differently from f27s. The pattern on the f27 bears some similarity to that on certain bowls, such as f38, and thus some functions might also have been shared. Products placed into f27 cups seem likely to have required further processing. In the kitchen, spices or herbs might have been placed inside and ground. In the dining room, the cup may have contained foodstuffs, such as curds, yoghurt or a sauce, requiring the use of a spoon. This does not preclude f27 cups from being used as drinking vessels, so long as the liquids that the cups contained required no processing from which wear would result. Stirring would not concentrate the wear in the centre of the vessel, nor result in a pattern extending across the entire base.

There are two possible causes of the very distinctive ring-effect wear pattern observed in f33 cups. Perhaps the least likely cause is residual traces of wine in unwashed cups. The acidic properties of the liquid might, over time, have eaten away at the surfaces. This explanation is not wholly convincing, since the damage consistently occurs in the wrong places - just above the junction of the base and the wall, but not within it. However, experimental work might be usefully undertaken to assess the effects of residual wine, say, on pottery surfaces. More likely is the suggestion that the f33 was repeatedly subjected to a single process, such as stirring. The unworn ring in the corner of the base and wall suggests that the stirring implements could not meet the corner, perhaps because they tended to have slightly bulbous use-ends. A spoon, naturally, comes to mind, but stirring rods, which have narrower rounded ends not unlike spoons, were probably more usual. The need to stir indicates that the liquid required processing within the cup. Beverages may have been sweetened with honey (perhaps implying a hot drink), or ingredients added to the cup to create something akin to a modern cocktail. The regular occurrence of the wear-ring in the f33 cup suggests that the form was indelibly associated with a specific function at Heybridge, just as a modern wine glass, or whisky tumbler, is defined by shape and tends to contain only certain selected beverages.

Wear patterns were noted in four forms, namely f37, f38, f44 and Curle 11, and affected mainly Central Gaulish pieces. Three distinct patterns were observed. Figure 344 shows the base of an f38 bowl with multiple linear scratch marks. These extend internally across the base and part-way up the vessel wall, stopping approximately at a point level with the flange. The scratches are short and have no set orientation. The stamp is slightly worn, but is otherwise not scratched. It is likely that a sharp pointed implement caused these scratches, probably a knife. The size and shape of the bowl would not allow extended cuts to be made, so items placed within the vessel were probably small. Assuming that the vessel enjoyed domestic use, the scratches may well have been made in the kitchen, with the vessel being used during the preparation of ingredients and when cutting small items, such as fruit. Alternatively, the vessel might have been placed on the dinner table and used by an individual diner in the same manner as a plate.

A second type of wear again affects an f38 bowl (not shown). Internal wear is restricted to the centre of the base. A circular pattern has formed, with the stamp almost completely worn away. Figure 346 shows an example of a developed form of this pattern. The wear extends to the lower part of the wall, with the base almost entirely devoid of slip. This sort of pattern was also noted on f37, f44 (Figure 347) and Curle 11 bowl types.

These use patterns are generally heavy, but the condition of the vessels where the slip remains is good. This suggests an intense, but directed usage of such vessels. In addition, a very even boundary between slip and wear can often be seen on the lower part of vessel walls, suggesting repeated processes and exclusivity of function. Again, use in the kitchen may be suggested, with vessels perhaps serving as mixing bowls or mortars. The vessel in Figure 346, with its more developed pattern, may have been used for longer, or more intensively.

Preservation of samian mortaria at Elms Farm was poor. Although many mortaria sherds were recovered, no vessel was complete enough for wear patterns to be fully identified. Sherds are worn to various degrees, but nearly always on the interior surface, and range from barely used to heavily worn. In well-used examples, wear generally extends towards the top of the interior surface level to the base of the collar, forming an even boundary around the vessel (Figure 348). The interior surface is often devoid of slip, and the trituration grits, when present, are often smooth with use. Figure 349 shows a Nene Valley colour-coated ware copy of samian mortarium f45. As with examples of its prototype, the wear extends to a level just below the collar. The interior surface has not been entirely utilised, however; the centre of the vessel is less worn than the side, and usage seems to have been concentrated in an area of the vessel wall towards the spout. This is consistent with its possible use as a mixing bowl. When mixing ingredients, such as flour and water, modern experience reveals that there is a tendency to tilt the bowl. In any case, the restricted pattern suggests repeated action of a single process.

Although no particular patterns were observed in this class, the wear on one vessel was unusual, and warranted further attention. This incomplete vessel comprised a Central Gaulish f31 base. Apart from the wear patterns, the base is in good condition with reasonably fresh surfaces. A ring of 'kiln grit' is present on the interior or top surface, indicating that some of this surface was virtually unused. There are three areas of wear evident. First, the underside of the foot-ring is worn, with very little slip remaining. The slip on the sides of the foot-ring is still present and in good condition. Secondly, a roughly circular pattern of wear is present on the underside of the base, within the foot-ring (Figure 350). The zone of wear almost meets the junction of the inner side of the foot-ring, while a ring of slip is present centrally within the prominent 'kick'. A third wear pattern can be seen on the interior surface of the base (Figure 351). Two opposing triangular patches of wear are present, maximum height 35mm, base lengths 25mm and 15mm. The apices of both patches almost meet in the centre of the base, extending out towards the outer edge. In the centre, at the peak of the 'kick' and covering the middle of a stamp of Priscinus (see Samian section) is a very small wear circle, 7mm in diameter.

The underside of the base has been used intensively. The good condition of the inner surface and the abraded foot-ring suggest that the vessel was used conventionally for only a short time prior to its possible deliberate breakage and rough trimming to remove the vessel sides. That the modified vessel rested on the peak of its internal kick is clearly shown by the resulting wear. The cause of the wear on the underside remains unknown, but its sub-circular pattern suggests circular movement on the part of the user. The triangular patterns on the inner surface support this explanation. These very specific patches suggest a rocking or swivel action, as if the piece had been fixed, restricting movement to a short turn clockwise and anti-clockwise. This is a very unusual pattern, for which no explanation is immediately apparent.

These wear patterns inform us that samian vessels were functional at Heybridge. Against the conventional view that samian was valued and looked after (cf. Willis 1998, 86), the wear-marks reveal that some vessels were not rarely seen heirlooms - delicately handled or brought out on special occasions - but served robust and mundane functions. Bowls and cups were not the exclusive preserve of the dinner table, but were used also for preparation and could become just as worn as mortaria. Members of ostensibly the same vessel class did not necessarily serve the same functions and were undoubtedly employed in a variety of household contexts. However, the wear patterns on all of the vessels in this study resulted from repeated processes, suggesting that these vessels served singular purposes. A bowl used for mixing was, by and large, always used for mixing, its function fixed by custom and practice.

There are a number of implications to be drawn from these observations. Some fine wares, and perhaps all, are likely to have been treated no more carefully than coarse wares. Distinctions between fabrics made through a microscope or hand lens do not necessarily reflect the functional or practical distinctions of a past society. Modern experiences, too, result in differing perceptions of ancient use. The f27 cup, for example, is a drinking vessel according to British archaeologists, but a 'sauce-dish' on the continental mainland (e.g. Schucany 2000, 123). Such labels are modern constructs, and without the evidence of wear-patterns or, better still, residues, assigning actual, as opposed to perceived, functions to vessel types is problematic.

It should not be taken for granted that all cups were used for drinking and bowls for eating. Potentially, the range of functions that vessels might have served and the social contexts in which the vessels could be employed can be increased. This can affect the interpretation of, say, burial assemblages. The function of a suite of accessory vessels recovered from a cremation burial cannot be pre-assigned. A suite comprising the seemingly standard flagon, cup and bowl should not be automatically given simplistic eating/drinking interpretations, but instead a range of activities may be represented.

With one exception, samian has formed the basis of this study. However, all colour-coated fabrics can be easily studied for use-wear. Clearly, the more complete the vessel, the more identifiable a pattern becomes. Wear on fabrics that were not originally slipped cannot be observed so clearly, but inferences drawn from the samian might also apply to copies of samian prototypes manufactured in non-slipped fabrics. As a matter of course, any signs of use on these copies should be noted to ascertain whether function, as well as form, was being copied. Experiments involving a range of processes and conditions could be undertaken to replicate wear patterns. Ultimately, a study incorporating a much wider dataset than that present at Heybridge is required in order to establish whether the trends established here are mirrored elsewhere.

Relatively large numbers of graffiti were noted during pottery recording. All fabric and vessel types are represented, although the preferred vessel classes seem to be dishes, beakers and jars. Graffiti can be loosely divided into two types, literate and non-literate, and both can be applied either before or after firing. Graffiti incised after firing, however, appear to be the most numerous. Archive drawings were produced, as a matter of course, for all graffiti and other marks noted on the coarse pottery. The samian was isolated from the pottery assemblage before recording work commenced on the coarse pottery, and the identification of graffiti on samian sherds was carried out by Brenda Dickinson. Archive drawings, therefore, were not produced for these.