The 1993-95 excavations revealed a new form of Anglo-Scandinavian settlement, with a gated entranceway and rectangular enclosures which, it was believed, replaced the Anglian settlement to the south in the last quarter of the 9th century, following Halfdan's land seizure. The intensified metal-detector survey of the northern area has not only revealed the further area of Anglian activity discussed above, but has also greatly increased the number of Anglo-Scandinavian finds. Their spatial differentiation now suggests two distinct phases of Viking Age activity.

The additional Anglo-Scandinavian finds are spread over a wide area, encompassing and extending somewhat beyond both Anglian areas of activity, but the majority were found in the northern area (Figure 21). They are largely bullion-related finds such as weights and silver melts, but also include some imported dress accessories.

The seventeen weights are all of lead and the first eight, found around 25 years ago, were not recognised as weights, or plotted, although it was noted that they were found in the northern area. The nine weights found in more recent times were plotted and all come from near the periphery of the northern part of this distribution. The weights were recently published, where it was noted that they contribute 'important new evidence for the existence and use of Scandinavian weighing systems in Viking-Age England' (Haldenby and Kershaw 2014, 106). Most of the weights conform to the Scandinavian light øre; weight unit of 24.42g, being multiple or sub-units of this, with just one being related to the heavier Scandinavian 'Dublin' øre; unit of 26.6g.

Despite having been found 400m to the west, along the east-west trackway, three additional Viking weights have been included in the database, in view of their proximity to Cottam B. As a result of additional detecting a further eleven weights have now been recovered from this western area, although there are no other associated Anglo-Scandinavian finds and they must represent a specific and separate loss. They are similar in form and patina to those from the northern area, but comprise roughly equal numbers of the heavy and light weight standards.

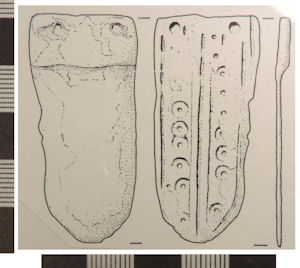

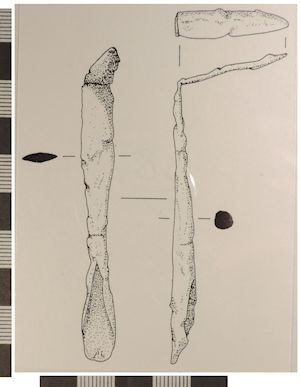

Further bullion-related finds include fragments of two balance beams, one from the northern area (Figure 22), the other from the south (Figure 23). A fragment of an Arabic silver coin, or dirham (Figure 24), may also have originated as bullion, although its late date, AD 928-9 (with arrival on site no earlier than the mid 930s), probably discounts a link with the other bullion-related finds that are thought to have been in use in the late 9th century. A silver sceat of Eadbert, c. 750 (Figure 25), perhaps obtained by the Vikings, even maybe at Cottam, is a good candidate for a piece of silver bullion, partly given its juxtaposition to the weights, well away from the other 8th-century coins in the Anglian occupation area to the south, but even more tellingly because of the presence of a deep test 'peck' mark, unique on such a coin, but characteristic of Viking silver testing of broad flan coinage. A large amorphous piece of silver melt has also been found, with one lobe characteristically hacked off, similar to many Viking ingots (Figure 26 - top left). A smaller piece of silver melt (Figure 26 - bottom right) similar to the latter, and a piece of beaten silver sheet (Figure 26 - top right) are also likely pieces of bullion, although neither is of classic Viking ingot form. Given the propensity of the Vikings for cutting up elaborate Anglian metalwork, sometimes for embedding in lead weights to personalise them (Blackburn 2011, 240), it is likely that what is believed to be an Anglian book mount fragment, roughly chopped along one edge, is another early Viking Age find possibly linked to the bullion economy (Figure 27). A further two crudely broken fragments of elaborately decorated 8th-century metalwork (Figures 28-29) may also have passed through Viking hands.

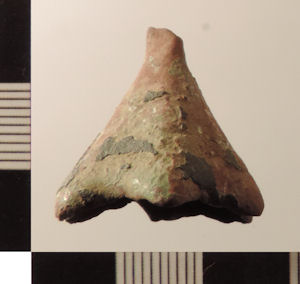

The broad distribution of these bullion-related finds is shared by four quite distinct dress accessories, each of which has continental or Scandinavian parallels. They comprise two Borre-style strap-ends with moulded interlace (Figures 30-31), one silvered and with ring-chain ornament, and each decorated on the reverse with a peripheral groove (whereas Anglo-Saxon examples have plain reverses); part of an ansate brooch with a flaring trilobite terminal (Figure 32); and a broad ribbed strap-end with ring-and-dot decoration (Figure 33). Each of these types of dress accessory had come into use by the mid- to late 9th century, with a strap-end with interlace from Fishergate, York (Rogers 1993, 1351-2), and ansate brooches and ribbed strap-ends from Kaupang, Norway (Skre 2011, 71, 76). Furthermore, in addition to a pair of bullion-related finds just two Anglo-Scandinavian dress accessories were found on the nearby Anglian site at Cowlam: a Norse bell and a ribbed strap-end with ring-and-dot decoration (Richards 2011b; 2013). These dress accessories are small in number but their rarity, and the fact each type is known from other 9th-century sites, gives added significance to the very different distribution they share with the bullion finds, compared to what is seen as the later, second phase, Viking material discussed below.

It is also notable that three out of the four dress accessories from this first Viking phase are broken, including both strap-ends with interlace. This is mirrored among the large assemblage of 133 Anglo-Saxon strap-ends found at the site of the winter camp of the Viking Great Army at Torksey, Lincolnshire, which appear to have been collected as scrap metal to be melted down (Hadley and Richards 2016b). The bullion finds and the dress accessories can all be seen as imports, perhaps the exchange system paraphernalia and accoutrements of an invading Viking force, the dispersed nature of the finds suggesting it was not at this stage intent upon establishing a focused settlement. Rather, the distribution is perhaps more consistent with a transitory presence, as also seen at the winter camps (Hadley and Richards 2016a; 2016b), by a faction of the Viking Great Army sometime in the mid 870s, engaged in stripping items of value from the former Anglian settlement.

The date of abandonment of the Anglian enclosure was always underpinned by a roughly broken fragment of a silver penny of Aethelberht of Wessex, 858 to c. 862/4 (Figure 34), found in the upper fill of a pit that also contained a human skull (Richards 1999a, 36). Single broad Anglo-Saxon pennies are very rarely provenanced in Northumbria, with only seven examples from the Wolds in total, although over twenty are known from Torksey (Abramson in prep; Hadley and Richards 2016b). The initial tentative suggestion (Pirie 1999) that it represented long-distance trade, following the decline of the styca, was always at odds with the insular nature of the other Anglian finds. In the context of the other hack metalwork this example can now be plausibly explained as having been brought to Cottam by a member of the mobile Viking army, presumably from previous activity in southern England. The coin and other bullion finds, not least the silver melt and the test-pecked sceat, perhaps obtained by dint of having been a 9th-century heirloom, along with the 'hacked' book mount, are particularly suggestive of Viking activity. A fragment of a silver penny of Burgred of Mercia (852-74) recently discovered at Yapham in the East Riding of Yorkshire has also been interpreted as having been brought north as a result of activity associated with the Viking Great Army (Griffiths 2015, 53). In the early 10th-century Viking cemetery at Cumwhitton (Cumbria) a styca of Eanred (810-41) was found in Grave 5, and is also interpreted as a curated object (Paterson et al. 2014, 113, 154). At Cottam two iron spearheads (Figures 35-36) are unusual finds for a settlement and may also relate to a visit by a part of the Great Army. The socket of one is silvered and inlaid with silver wire, and is of a type frequently found in Scandinavia (e.g. Roesdahl 1982, 136-7; Williams et al. 2013, 106-11). It is not possible to say how long this phase of activity lasted but, as with the winter camps, our refined chronology may be allowing us to capture a group of material that was deposited in no more than a single event within a year, possibly around the seizure of York in 866-7 or subsequent years, or as a result of the land partition in 876.

In the second phase of Anglo-Scandinavian activity the finds area occupies a fraction of that of the first phase and is denser than this and broadly coterminous with the northern spread of Anglian finds. The great majority of later Anglo-Scandinavian finds come from within or immediately around the area of the Anglo-Scandinavian farmstead with its imposing gated entrance, identified in the 1995 excavation, which is now thought to represent this second, 'Anglo-Scandinavian' settlement phase (Figure 37).

As noted above, the arrival of the Vikings and their early activity on site could well be related to the demise of the Anglian settlement and could then have merged into the Anglo-Scandinavian settlement phase, so that the complete transition may have been quite rapid, sometime in the mid-870s. As with Anglian finds and those from the transitory Viking phase, many more relating to the Anglo-Scandinavian farmstead are now available for study. However, as is seen elsewhere, their numbers do not approach 9th-century Anglian finds numbers but, compared to these, they are more varied in type and are not dominated by pins, strap-ends or coins. Numbers of plate head pins, one of the main surviving collared pin forms, are quite high but they may not have remained in fashion for long, soon fading from use as was the case with the other pin forms and the strap-ends. The demise of these dress accessories in the late 9th century is borne out by the predominately 10th-century site of Coppergate as this produced relatively few identifiable collared pins and no Thomas class A strap-ends (Mainman and Rogers 2000, 2568-70, 2576-83).

The finds from the Anglo-Scandinavian farmstead and the northern Anglian finds are interspersed and some generic forms, such as knives and sandstone hones, and some copper-alloy finds, such as a needle, cannot be assigned to one or other phase at this stage. The hooked tags are also found in similar numbers in southern and northern areas and some of those from the north may be Anglo-Scandinavian dress accessories, since the type is also found on other 10th-century sites such as Coppergate (Mainman and Rogers 2000, 2576) and Stamford Bridge (Haldenby and Richards in prep.).

Many finds are recognisably Anglo-Scandinavian and these are often dress accessories of new form and decorative style, found mainly in the northern area. Among these are the thirteen plate head pins and the five pins with rising curved faces. The three Norse bells (Figures 38-40) have been studied (Schoenfelder and Richards 2011) and since several dozen are known from the Danelaw but none from Scandinavia; they are thought to be colonial Viking innovations, of likely decorative use. The two lead disc brooches (Figures 41-42) are similarly thought to be of local inspiration and manufacture, several coming from Coppergate (Mainman and Rogers 2000, 2571-4). However, the three strap-ends with multiple animal heads are found in Scandinavia and other 9th-century English sites (Haldenby and Richards in prep). Only the Jellinge design on the copper-alloy disc brooch is a recognisably Viking art style from this period (Figure 43). The strap guide (Figure 44) is included owing to the presence of parallels from Coppergate (Mainman and Rogers 2000, 2568); also to be included are three buckles, two with zoomorphic protruding leading edge (Figures 45-47); the five lead spindle-whorls (Figure 48a-e) and the two rings in sheet copper-alloy with ring-and-dot decoration (Figures 49-50). A number of similar lead spindle-whorls are known from the Viking winter camp at Torksey (Hadley and Richards 2016a; 2016b). The schist honestones, along with the Torksey-ware sherds, are also thought to belong to this second Anglo-Scandinavian settlement phase.

Compared to the Anglian finds, much plainer decoration is seen on much of this new material, the Trewhiddle style no longer being abundant, seemingly replaced by ring-and-dot or pellets and lines, such as those on the lead disc brooches, or by animal heads, as seen at the terminals of many Anglian strap-ends, but here simply repeated along the length of the strap-end. Vestiges of inlay on one of the buckles appear to represent a late example of Trewhiddle decoration. The Jellinge-style brooch stands out as an elaborately ornamented piece, and may well not be of local manufacture, a similar example having been found during the High Street excavations in Dublin (Ó'Ríordáin 1971, fig. 21c).

The increased use of ring-and-dot ornament at Cottam B in the Anglo-Scandinavian period is illustrated by the fact that 38 finds from the northern area display ring-and-dot ornament or an abbreviated version, comprising either drilled dots or raised pellets. This contrasts with the southern area where there are only 11 objects with ring-and-dot (Figures 51-52). (Pins with polyhedral heads are excluded from the calculations since they are present in the northern and southern areas, and they are believed to be earlier.) The extension of ring-and-dot decoration from these pins to other forms of metalwork possibly occurred because it was easier to create than the more elaborate animal ornament. It seems to be a distinctive feature of the hybrid Anglo-Scandinavian culture in the region, although the increase in popularity of ring-and-dot ornament in the 10th century has also been observed elsewhere, such as at the settlement at Yarnton (Allen and Dodd 2004, 280).

The only definite late 10th-century find remains the half-coin of Aethelred (AD c. 1000) (Figure 53) found several years ago, and there is an absence of later 10th/11th-century decorative styles or dress accessories, such as pins with lozenge-shaped heads and 'D'-shaped buckles with stylised animal heads biting the pin bar ends. Hence the conclusion remains that the settlement was abandoned around the second quarter of the 10th century, with the transfer of subsequent settlement to the sites of the medieval villages of Cowlam and Cottam (Richards 2013).

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.