Cite this as: Gruber, G. 2017 Contract Archaeology, Social Media and the Unintended Collaboration with the Public — Experiences from Motala, Sweden, Internet Archaeology 46. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.46.5

This article draws on a series of contract archaeology projects undertaken in the town of Motala, Sweden. It focuses particularly on a unique event that occurred as a result of the use of social media. In this context, social media here means Internet services or platforms, applications and technologies, such as blogs, message boards, podcasts, wikis, vlogs, etc., where the content is generated by the users of the services and enables people to interact with one another online. The purpose is communication, collaboration and/or sharing through text, pictures, audio and video (Cann et al. 2011, 7; Jeffrey 2012, 558). Within Swedish contract archaeology today, there is a lack of deeper knowledge about public communication and social media engagement. At the same time, archaeology is expected, in a qualitative way, to live up to political goals and embrace communication with the public in order to meet the demands of society.

The Motala project and the specific social media incident that is presented in this article are an example of how we, as contract archaeologists, collaborate with the public in our daily work, even though we are not always aware of this. Our interactions or collaborations might be unintentional and, often, unintended. Sometimes they are even unwanted and unwelcome.

With this article, I aim to illustrate how development-led archaeology generates a wide scope of meaningful uses of the past for a broad range of people, but also how our roles, as archaeologists, are changing as a consequence of the use of social media

In Sweden, as in other countries, contract archaeology is part of social planning and development. Ancient remains and monuments are protected for the future under the Swedish law on cultural heritage, (SFS 1988, 950, 2 Chap.). This legislation is based on a well-established notion of the aesthetic value and knowledge that is believed to be inherent in the heritage. This moral outlook has been developed alongside specific ideas of authenticity. The duty of present generations is to protect and preserve material objects, places and landscapes, so that they can be passed on to future generations, for their education and to create a sense of shared identity with a foundation in the past (Smith 2006; Smith and Waterton 2009).

Swedish contract archaeology is based on a tripartite relationship involving the County Administration Board, the developer and the excavating institution. The County Administrative Board settles conflicts between preservation and development by making it a condition for the developers to finance archaeological excavation in cases when they want to exploit land where there are ancient remains (KRFS 2015:1).

This process is often described in a linear manner, with three distinct steps involving archaeological documentation, scientific analysis and interpretation, and communication of results (Gruber 2010, 254). The general public is not an active part of this process. The public is seen as the receivers of the knowledge the archaeologists produce and communicate through, for example, guided tours, exhibitions, lectures, and texts (Svanberg and Wahlgren 2007; Arnberg and Gruber 2014).

In recent years, however, we have witnessed a shift in the official rhetoric when it comes to the public side of this practice. The National Heritage Board i.e. the national supervisory authority, has recently stated that contract archaeology must 'become more communicative and respond to society's demand for information, knowledge, and relevance. To achieve this requires a shift of focus from the intradisciplinary results to the public assignment in a broader perspective' (RAÄ 2012, 6).

On 1 January 2014, parts of the Swedish law on cultural heritage concerning public communication were rewritten. As a consequence of this, today, the County Administration Board can demand that the findings from archaeological investigations resulting from development must be communicated to the public (SFS 1988, 950, 2 Chap. 13). This means that developers can be made responsible for the cost of public activities in connection with projects in contract archaeology. In this context, the County Administration Board has an important public mission to implement the goals of Swedish cultural heritage policy, which is to promote people's participation, a sustainable and inclusive society, and a holistic outlook through which the cultural heritage is used and protected in the work of community development (see https://data.riksdagen.se/fil/95197548-21B8-42BF-80B8-8C96BFA0572C).

Motala is a town in the county of Östergötland, in south-east central Sweden, and has approximately 42,000 inhabitants. The town received its charter in 1881 and is located where Lake Vättern flows into the River Motala Ström and Göta Canal. The canal was built at the start of the 19th century to link the Baltic with the sea to the west. The construction of the canal brought a need for engineering works, and the company Motala Verkstad was founded. In the 20th century, larger companies such as Luxor and Electrolux established factories in the town. Motala acquired the character of an industrial town and became part of the growth of modern Sweden. Today, many of the industries have closed, with increased unemployment as a result. In the policy documents of the municipality, it can be seen that the politicians are now focusing on strategies to create jobs, on city branding and on building local identities (Arnberg and Gruber 2014, 164).

In 1995, the Swedish Transport Administration decided to increase the railway capacity through the town with a second track and new bridges over the river and the canal. During the planning process, a previously unknown Mesolithic settlement site was discovered (Figure 1).

The contract archaeology fieldwork was carried out between the years 1999–2003 and 2009–2013. The excavations were comprehensive and consisted of several large archaeological projects on both sides of the River Motala Ström. The work was carried out by the Swedish National Heritage Board, Contract Archaeology Service (as of 1 January 2015 The Archaeologists, National Historical Museums, Sweden) and the Cultural Heritage Foundation.

One of the dominating narratives that we communicated to the public was based on the idea of the site as a large Mesolithic settlement complex — a focal point in the landscape. This derives from the key position of the site viewed from geographical, communication, and resource-centred perspectives. This interpretation is also linked to the finds of thousands of stone tools, decorated bones and antler artefacts, as well as traces of dwellings, specialised craftsmanship, fishing equipment, ritual depositions and several burials (Hallgren 2011; Hallgren and Fornander 2014; Molin et al. 2014).

The archaeological projects have been accompanied by ambitious work on public communication, commissioned by the County Administrative Board (Figure 2). The work has mainly followed a broadcast model, that is, a one-to-many concept of communication. For the purpose of informing and educating the public, we have used a wide range of activities. There was also a wish to legitimise the archaeological work that was conducted on behalf of the citizens and financed by public funds. The channels of communication we used can be divided into five subgroups, each containing a number of different methods: personal meetings, printed material, presentations, news media and Internet/social media (Arnberg and Gruber 2014, 165f).

Over the past decades, the development of digital and web-based technologies has created a multitude of interfaces; this has changed the flow of information between people, communities and institutions. In 2015, 93 per cent of Sweden's population had access to the internet and over 95 per cent of the inhabitants aged 8-55 used it. Seventy-seven per cent of Internet users had visited social networks and 70 per cent had used Facebook (Findahl and Davidsson 2015, 40ff).

For those within the cultural heritage sector, digital techniques and social networks have changed the dynamics of encounters with the public. In Sweden, this development coincides with a long-standing and lively discussion concerning the meanings, values and societal relevance of archaeology and cultural heritage (e.g. Burström 1999; Karlsson and Nilsson 2001; Högberg 2003; Pettersson 2003; Svanberg and Wahlgren 2007; Gill 2008; Gruber 2010). It also coincides with a shift in Swedish heritage policy that has attributed greater importance to diversity, democratic participation and economic interests, and reduced the focus on national identity (Beckman 2005).

The use of new digital technologies has long been influenced by technocratic enterprises, particularly within the GLAM sector (Galleries, Libraries, Archives, Museums). The aim has been mainly to digitise and standardise archival data and other source material, in order to make it more user-friendly. Digitisation can be said to have worked towards the democratic goals of heritage politics, since it invites citizens to interpret cultural heritage that has become digitally available (Axelsson 2015, 9).

In recent years, a change has occurred in the use of digital media among cultural heritage institutions, consisting of a shift from didactic aims to a focus on participation and exchange of knowledge. Earlier, digital methods were mainly regarded as tools aiding heritage professionals in their cataloguing work. Today, they are attributed much more value for outward looking communications (Axelsson 2015, 12). The public is thus no longer seen as users only, but also as participants and creators. Ultimately, this change could subvert established hierarchical relationships between institutions and individuals; the boundaries between these two groups are becoming porous and generate a 'shared' authority (Adair et al 2011; Jeffrey 2012, 557).

Organisations within Swedish contract archaeology have been presenting excavations and reports on websites for a long time. Social media such as blogs, Facebook, Flickr and Twitter have only lately become commonly used, particularly as a supplement to the traditional forms of public communication during fieldwork. These are seen as tools that can fulfil several purposes e.g. establishing new relations, promoting dialogue, and sharing knowledge (E-delegationen 2010; Larsson 2013). In contract archaeology, this was characterised (Gruber 2013) as a way to:

In our work as contract archaeologists we create a large amount of pictures and narratives that are linked to sites, the past and our own practical work. Many people are interested in reading about this work and follow us over time. They also want to take part and discuss matters. Contract archaeology is in part slow work, conducted in several stages (see above) and published in a variety of ways (reports, scientific articles, popular science articles, etc.). For many people, the moment of discovery, when an artefact is unearthed, is fascinating, adding to the attractiveness of archaeology and the past. The situational dimensions of archaeology are thus well suited for the feeds of social media.

One purpose of using social media in the Motala projects was to increase opportunities for the public to follow our work (Table 1). Regardless of where people happened to be located, our aim was to give an insight into the excavations and the emotions these generated.

Through the work with social media our aim was to:

| Activities | Number | Years |

|---|---|---|

| Digital newsletters | 25 | 2000-2003 |

| Homepage, updated | 10+ | 2000-2016 |

| Blog, posts | 211 | 2009-2016 |

| Facebook, posts | 804 | 2011-2016 |

| YouTube, video clips | 14 | 2011-2016 |

| Podcast, episodes | 9 | 2013 |

| Total | 1073+ |

The content of the posts published by the Motala project in social media mostly concerned a handful of traditional themes such as: finds and artefacts; features; interpretations of features and the past; the cultural heritage of the area; cultural heritage work from a broader perspective in society; fieldwork and methods; moments and events occurring during the course of the work; announcements of events; links to other sites with similar activities and/or similar archaeological remains.

In 2009, when the project entered its second phase, we started to write a blog. The purpose was to write about our work and the project, while creating an opportunity for dialogue with the public. We soon realised that no dialogue was forthcoming, at least not via our blog. Discussions, instead, occurred on other websites and media, and we will return to these later in this article. Consequently, in 2011 we opened a Facebook account, considering Facebook a quicker way than the blog to share the pictures and narratives that we produced. Facebook was also better suited to convey the manifold feelings and emotions evoked by the fieldwork.

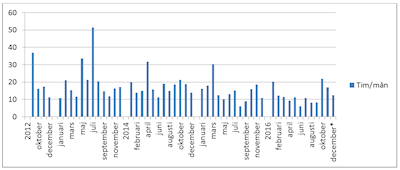

Furthermore, in the same year, we started to produce simple film clips that we posted on YouTube. Most of these were around 3-5 minutes long and the filming was completed at a relatively amateur level. However, we did also employ a professional film producer who created an 18-minute long documentary. In the case of Facebook posts, pictures and texts disappear in the continuous feed of events, and comments and dialogue were at their height when we undertook our own posts. In contrast, we have noted that our film clips on YouTube are constantly finding a new audience. Between September 2012 and December 2016, the 14 film clips from the Motala project were viewed for an overall duration of 866 hours (36 days around the clock) and an average of 16.6 hours per month (Figure 3).

Social media are steered by a sense of the here and now and immediacy. This is quite contrary to how archaeologists usually create and communicate narratives. Social media can challenge our usual way of acting and below I will give an account of a specific incident. In many ways, this is an extreme example, but it can contribute to highlighting the way contract archaeology creates broader values in society than those traditionally associated with the practice of our work.

In 2010, we found a tool made from red deer antler (Figure 4). The use wear on the tip of the tool showed that it had been used for pressure flaking and retouching flint. Finding a 7,000-year-old tool made of antler is in itself a sensation. But it was the shape of the handle that created amazement and great amusement on the part of the excavation team. In our eyes, it simply looked like a penis!

The very moment we found this tool, discussion began whether we should go public with it or not. However, we did not feel that a regular press release was the right approach. This object was potential dynamite, and our knowledge about phallus-symbolism or fertility cults in a Mesolithic context was limited. Was it a phallus at all?

At the same time, it was a fascinating object; we wanted to show it to the people who followed the excavation in various ways. Perhaps somebody could help us understand the design of the object. There was also a time aspect to keep in mind, since the news about the find rapidly started to trickle out through the private use of social media by the excavation team members. So we posted a short text and some photos of the object on the project's blog. After all, the blog did not have that many followers, and we assumed that most of them would be our friends or fellow archaeologists. In our mind, this was a more low-key channel of communication.

Some Google searches gave us more material for the blog post. On one website, we found a story about a sculpted and polished phallus found in a German cave. According to the website, a professor from Tübingen University speculated whether this find had been used as a 'prehistoric sex toy'. So in our blog post we jokingly asked whether we had found Scandinavia's oldest dildo. This blog has been closed since 1 January 2015 (the reasons for this give rise to questions about web-based technology and sustainability. To save space, this is not discussed in the article). This was a provocative angle, but considering the intention of the blog was to mirror the atmosphere of chuckles and giggles the explicit form of the artefact evoked among the excavation team, it was an illustrative post.

The blog post was published on 15 July at 11.26 am. On the same day, at 2.38 pm, a Swedish colleague picked up our story and presented the find on his English-language blog, Aardvarchaeology, under the heading 'Stone Age dildo found in Sweden'.

A couple of days later my mobile phone rang. The editor of the website, LiveScience, was on the other end. She phoned me from NYC and wanted to ask questions about the dildo. In the following interview, I tried to steer the conversation away from the sex angle and instead emphasised aspects such as the function of the tool. I talked vividly about the Mesolithic site and its location in the landscape, describing how it was situated close to the River Motala Ström, and how the preservation conditions were exceptional, resulting in an unusually large amount of early Stone Age organic material. On 20 July, LiveScience.com published a text with the heading 'Stone Age Carving: Ancient Dildo?'.

The story was then taken up by major American media companies. Fox News published it on their website with the heading 'Stone Age Carving or Ancient Sex Toy?', referring both to the Aardvarchaeology blog and the LiveScience interview. CBS News published a photo of the tool in the section 'Techtalk'. They used a picture taken from our blog, without retouching it. Therefore, the Swedish text 'Det är inte längden som räknas' ('Size doesn't matter') appears on their website.

From the US, the story spread over the world and returned to Swedish newspapers. Two narratives dominated now. One was about the Stone Age artefact, sex and sensation. The other one focused on the media hype. A Swedish tabloid hunted down the two blog post writers just to ask the classic question, 'How do you feel?', in reference to the find. A photographer confronted one of them outside the front door of her house. In the Sunday edition of the newspaper a short interview appeared including an information box showing her civil state, number of children, place of residence and income (Aftonbladet 2010).

In Swedish news media, the story exploded over a couple of days and then quickly disappeared. On the internet, the story rolled on, in a large number of websites. Some of them were of the shabbier character. The comment fields were filled with sexist remarks and opinions in all imaginable, and not always flattering, directions.

If we stop here, it is clear that as the editor of the project's blog, I could be accused of being naïve for not thinking about the explosive force of the word dildo. In the context of this article, though, the dildo story is a useful prism for discussions about contract archaeology, social media and public communication.

The excavation in Motala was characterised by heavy layers of clay and gyttja combined with laboriously monotonous wet sieving. On the other hand, there was always the possibility of finding objects of organic material with a quality of preservation otherwise only described in literature and in museum exhibitions. As mentioned above, our use of social media was not only to communicate the discovery of finds and archaeological contexts but also a way to give insights to a broader public of our daily fieldwork. This time the blog post was about a strangely shaped object.

The very moment we posted the find on our blog, we also lost control over words and pictures. The story immediately took on a life of its own, which highlights fundamental aspects of power and boundaries. As archaeologists in the cultural heritage sector, we are, both as individuals and as institutions, ascribed a high level of credibility and authority. We facilitate public access to archaeological information by using academic skills and knowledge. This has been described as an interaction 'which involves trust on behalf of the public and within the discipline, public deference to the archaeologist's accumulated knowledge base and skill set, the public performance of the professional's archaeological experience, and the public acceptance of institutional affiliation as an embodiment of that expertise' (Richardson 2014, 250).

Our way of communicating with the public can be described as a performance in front of an audience, or society. In this context, the concept of Front stage and Back stage can be useful to describe and understand what happens in the relationship between the roles that we (as archaeologists) play at a given moment and the various audiences these roles involve. Front stage, our acting is open for judgement from those who observe the performance and encounter the narratives. Back stage, in contrast, is a place where we can discuss, examine and develop the archaeological practice/performance without revealing ourselves to the audience, or public. Back stage also allows us to express aspects about the profession and criticise the contract archaeology system in ways that would be impossible or perhaps even unacceptable to the public (Goffman 1959).

In the field of rhetoric, digital technologies and social media are often understood as a means of increasing the transparency between archaeologists/institutions and the public, between front stage and back stage. It is a way to lower the barriers and open up a discipline to which few outside the profession have access. In our project too, this was the main reason for using social media. However, the question is whether new technologies really do break down boundaries between what can or cannot be expressed, or whether they just lead to new lines of division being drawn. In our case, it is obvious that there is still a line and, with the aim of being transparent, we crossed it. We published an internal joke loaded with aspects of sexuality and sensation and the irony hit back (Figure 5).

Narrative structures about the past are never an expression of individuality. Instead, they are part of a broader, well-established grammar that governs how narratives are shaped and communicated. This means that the stories we created as part of the excavations in Motala have no meaning in themselves. They only take on meanings in encounters with others. In these interactions, every individual has personal frames of reference that affect the interpretation (Dicks 2000, 75).

In the encounter with social media, our use of one small word resulted in vigorous reactions that triggered all sorts of sentiments. Everyone who came across the story related to and handled the content according to their own presuppositions, morals and/or interests. Some people saw the humour and laughed at the situation and at us. Others took a more critical approach. Two students of journalism at Stockholm University questioned our way of managing the blog in an essay on archaeology in news media (Hedman and Helles 2011). Others again were openly angry and accused us of being careless in the way we presented Mesolithic finds. A man from Norway told me off on the phone, because a Norwegian tabloid had published a simplistic, stereotyped article about phalluses as a result of our blog. Prehistoric phallus symbolism happened to be his special field of research. We were debilitated by the situation and embarrassed that our names were associated with this story. Naively, we even hoped that maybe the whole thing would blow over and disappear if we just stopped talking about it. Some embraced the story and made use of it in their own way (Figure 5).

If we look at the dildo experience in a broader perspective, it is obvious that just through our physical presence as archaeologists, doing archaeology, at the site in Motala, a multitude of narratives were established. Many of our statements on social media, but also on guided tours, in lectures, in newspaper interviews, etc., concerning specific finds, the archaeological site, the Stone Age as a prehistoric period and so on were additionally transformed into new stories and were included in other networks of narratives. Among these, we find down-to-earth themes, but also themes touching reverential, macabre, or violent aspects of the past. For instance, the website Cracked.com mentioned a ritual deposition of human skulls, which was discovered at an archaeological excavation of an ancient small lake adjacent to River Motala Ström in 2009 (Hallgren 2011). This was listed as one of The 7 Most Terrifying Archaeological Discoveries: '…some ancient society probably butchered 11 people in a stone hut at the bottom of a lake bed, and then put the pieces of one dead person's skull inside the brain space of another person, like the world's most godawfully horrifying nesting doll'.

Sometimes these stories are based on our identification with people of the past, other times the narratives emphasised exoticism. Some narrative figures stressed continuity, while others pointed out change and progress. The stories are both parallel and contrasting in character. As archaeologists, we need not necessarily like all these narratives. We might even have to take a stance against them for ethical, democratic, professional, or personal reasons (Aronsson 2004; Arnberg and Gruber 2014).

In global as well as local perspectives, the narratives gain meaning through the ways in which the public choose to use them. In the local context, for example, different actors used the stories of the Mesolithic site in situations that were significant for them. The past as well as archaeology became tools to solve the problems they were dealing with. For instance, the town of Motala has been associated with post-industrial trauma. In the light of this, we saw how the town politicians used the Stone Age remains as a way to brand the city of Motala and promote local identity (Motala C-Media 2012):

Motala is a historic place. We know that people have lived here since the Stone Age. We who are living and working here now are not surprised — Motala has a high quality factor.

In heritage processes, our role as archaeologists varies between being of central importance and having a lesser part to play. In the global media landscape where information flows across multiple web-based platforms, institutional contexts, national borders, and so on, it is less important who actually publishes a text or a photo. In the media convergence, meaningful stories about the past, or about specific places, are used in identity processes by individuals as well as by communities (Axelsson 2015, 13; Marty 2014). This is not new knowledge per se. Nevertheless, in the context of Swedish contract archaeology and in relation to public communication and the use of social media, this is an important experience that should be considered.

One important question that has been raised is whether our use of social media actually creates interactions with new individuals and groups in society or just increases the frequency with which existing audiences engage with archaeology (Bonacchi 2012, xv).

Even if both Facebook and YouTube supply simple statistics about users' gender, age and location, we unfortunately do not have any qualitative information about the people who have interacted with us through social media, which makes this question difficult to answer.

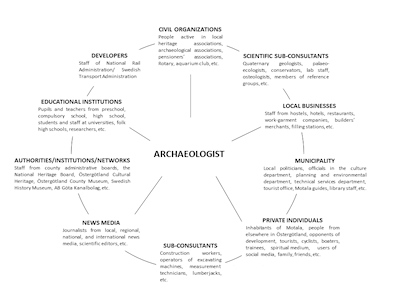

A method of analysing our audience is to survey those who have been in direct contact with the archaeological project. Figure 6 shows that a large number of people are involved in creating narratives about the site in Motala, far more than the three actors who are linked directly to the management system of contract archaeology (the county administration board, the developer and the archaeologists). It is obvious that the so-called general public cannot be understood as a homogeneous mass with uniform interests and goals when they encounter archaeology. Instead, the umbrella term covers a wide range of individuals, communities and institutions that are related to, for instance, the public, the civil or private sectors of society.

While Figure 6 demonstrates a large number of both actors and encounters, it is obvious that these hardly represent the whole population of Motala. There are gaps in our relations with the public, despite a great number of public activities. In other words, the question still remains of how we can develop methods that include, engage and empower groups in society who are not reached by the established activities.

Despite the increasing demands on the management of contract archaeology to broaden public participation and better satisfy society's increased expectations, still very little of this features in our everyday work. Both authorities and archaeologists have found it difficult to develop qualitative methods that aim beyond the scholarly framework (Arnberg and Gruber 2014).

The use of social media as part of public communication in the Motala projects highlights some fundamental questions concerning public empowerment, how narratives are created and how the past is used in meaningful ways. This case also shows that the shift in contract archaeology to include participatory or collaborative practices is already in progress even though we are, perhaps, not really aware of it. This shift does not bring lower levels of heritage interpretation skills and the dumbing down of contents, but, rather, it requires up-skilling and learning how archaeology can be communicated through digital and web-based technologies. It is a mental shift in the way that we understand communication.

If our goal is to address society's various interests in archaeology, it is essential that we develop a greater awareness of the wider range of communication pathways that can be opened up by social media to unlock the public values of heritage.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.