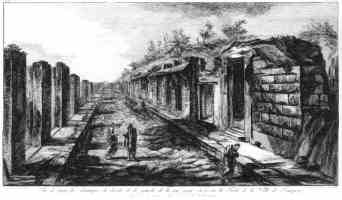

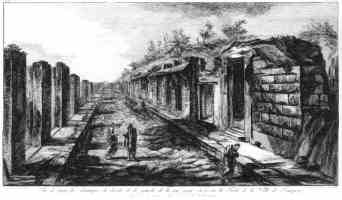

Figure 1: Francesco Piranesi's view of the via Consolare with the House of the Surgeon on the far right (after Fino 2006, 74)

Despite modern technical achievements, conveying daily Roman life to a non-specialist audience is not an invention of the computer age. Attempts to re-create Roman domestic life in Pompeii have been made in various forms since the site's rediscovery in the mid-18th century. From Piranesi's engravings of the ruins populated by the ghosts of the past (Figure 1) to colourful scenes of luxury from the likes of Domenico Morelli and Sir Laurence Alma-Tadema (Figure 2), the desire to be transported back in time through the medium of artistic vistas of antiquity has existed almost as long as the ruins themselves have been uncovered.

Figure 1: Francesco Piranesi's view of the via Consolare with the House of the Surgeon on the far right (after Fino 2006, 74)

The familiarity of the format works in their favour and they all benefit from the introduction of human characters and, in the later works, colour and the trappings of daily life. It is easy to see the difference this makes when viewing these works. Piranesi's engravings, devoid of colour and set in the ruins as they were in the late 18th century, are designed to highlight the eerie qualities of the site as it was then.

Figure 2: Confidences by Laurence Alma-Tadema (© National Museums Liverpool (Walker Art Gallery) used with permission)

Morelli and Alma-Tadema's vibrant slices of ancient life serve as a contrast, and benefit from colour, clutter and the sense of living, breathing beings going about their usual, and sometimes unusual, business. Morelli and Alma-Tadema's work also undoubtedly carries with it the trappings of Romanticism and illustrates the degree to which visualisations are not only windows into their ancient subjects but also products of the era of their creation. Somewhere between the two lie the creations of such artists as John Martin, James Hamilton and Karl Brjullov, who all depicted the destruction of the city in apocalyptic detail (Mori 2003). Here the focus is on the terrific forces unleashed by the volcano rather than either the town as it was in everyday life or the ruins that were uncovered so long afterward.

The different styles pictured here are an early example of an issue I will try to address in this article; anyone seeking to use Pompeii as the subject of their art has to decide which elements to include and which to exclude in order to achieve the desired effect. All speculative reconstruction has an artistic element as a result of these choices and the process behind deciding on what goes into an image or animation is similar to that followed by artists using less technological approaches than computer-generated 3-D models. More ancient detail in Piranesi's engravings would have changed their tone to one resembling Alma-Tadema's vibrant gaiety. Each artist has selected an approach and included the details they thought necessary to illustrate it, yet it is the gulf between the eerie qualities of the site as the tourist experiences it and the vibrant domesticity evidenced by archaeology that makes visual attempts at reconstruction so important to modern visitors.

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s)

URL: http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue23/3/intearly.html

Last updated: Tues Feb 5 2008