Volcanic eruptions were, with most certainty, a deeply embedded social element of past life in the Barú region (Holmberg 2005; 2007a; 2009). While the most recent eruption (estimated to have occurred at some point between the 14th and 16th centuries AD) seems to have had a strong impact on the surrounding landscape, the eruptions that preceded it seemed to have had little physical impact on pre-Columbian occupation. Eruption was, however, a relatively frequent event over the longue durée that would have had a strong experiential impact on memory and oral history. I suggest that one result of this could have been the utilisation of volcanic materials in a purposeful appropriation of the telluric power of the volcanic landscape.

Nineteenth and early 20th-century ethnographic studies indicate that considerable valence was attributed to stones and rocks in the Chiriquí past. The Bribrí indigenous groups of the Talamanca region of Costa Rica and Panamá, for example, believed that power came from associations between the stones and animals (calculi), which allowed shamans (Awa) to use them for purification ceremonies, rain-magic, and healing the sick (Gabb 1913; Joyce 1916, 103). This form of culturally held 'value' attributed to the stones did not translate into the contemporary period, at least not for late 19th and early 20th-century grave looters or collectors. This, in effect, creates an archaeological opportunity: if stones provided cultural 'value' in the past when graves were constructed but not in the 19th and early 20th centuries when they were heavily looted, data can still be sought from the grave construction materials not removed from the cemetery areas.

Though they were certainly more interested in the objects held within the graves, antiquarian and early archaeological descriptions of Boquete area burials note the characteristic use of dacite slabs and basalt columns in pre-Columbian grave construction (Bateman 1860 ![]() ; Bollaert 1860

; Bollaert 1860 ![]() ; de Zeltner 1866

; de Zeltner 1866 ![]() ; Holmes 1887

; Holmes 1887 ![]() ; 1888; Wassén 1949

; 1888; Wassén 1949 ![]() ). These stones were not worked or altered significantly from their original forms once quarried.

). These stones were not worked or altered significantly from their original forms once quarried.

Figure 34: Boquete area grave construction schematised by Linné (1936, fig. 1)

Figure 35: Boquete area grave construction schematised by Wassén (1949, fig. 6, Grave 1)

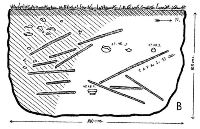

Figure 36: Boquete area grave schematic schematised by Wassén (1949, fig. 18B, Grave II)

Though most of the grave contexts I examined in fieldwork were looted, I did excavate one intact grave in the midst of three disturbed graves at the BE-16-KH KOT site (BE=Boquete; 16=the site number; KH=the initials of the excavator; letters were assigned to each 1 × 1m unit opened in alphabetical order; KOT signifies the name of the site used in the field, as it was on the Kotowa coffee farm]). The grave found in the KOT-J unit was intact while three adjacent graves (the combined units of KOT-A/I, KOT-F) were disturbed due to natural settling of the grave, the frequent seismic events in Boquete, the heavy equipment used in construction of the house foundation that uncovered the graves, and long-term avocational looting in the area [Schematic of BE-16-KH test units] . It is significant to note that the intact grave found in the KOT-J unit represents the first radiocarbon-dated grave in the Chiriquí area of Panamá, despite the many thousands of graves that have been opened since the late 19th century.

Figure 37: Construction and grave site at BE-16-KH KOT, looking west toward the Volcá Barú (13km distance)

The graves I excavated from this cemetery do not match any of the construction styles described in prior discussions of Chiriquí burials (de Zeltner 1967 [1866 ![]() ], 17-20; Holmes 1888; Joyce 1916, 107-9; Merritt 1860

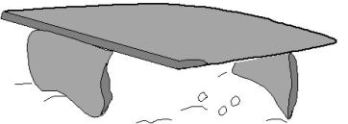

], 17-20; Holmes 1888; Joyce 1916, 107-9; Merritt 1860 ![]() ) and seem to represent a yet-undocumented style of grave construction. All were built using a carefully stacked wall of basalt columns created when lava flows cool and form crystalline structures. Dacite slabs, or flat volcanic capping stones, overlapped one another at an angle to create a roof.

) and seem to represent a yet-undocumented style of grave construction. All were built using a carefully stacked wall of basalt columns created when lava flows cool and form crystalline structures. Dacite slabs, or flat volcanic capping stones, overlapped one another at an angle to create a roof.

Figure 38: Photo of grave construction materials in situ at the BE-16-KH KOT site

Figure 39: Photo of grave construction materials in situ at the BE-16-KH KOT site

The graves lacked a stone floor and the burial cavity was lined with stone only on the two longest walls. Grave goods were found roughly 1m below the surface level, though exact depths were obfuscated as heavy machinery had stripped the surface of the entire construction area.

The dacite slabs in KOT-A/I combined unit, KOT-F unit, and KOT-J unit were each angled with a 315°-320° azimuth [View dacite in digital archive]. As I had seen illustrations of Chiriquí graves lined with flat capping stones (Barillas 1982; Linné 1936; Wassén 1949) I assumed upon excavation of the first grave that this angle was the result of settling or disruption. The uniformity of the angle and the integrity of the intact KOT-J unit grave construction, however, lend credence to the angle as an intentional design. Though no illustration was provided, this slanted roof does match an ethnographic description of Bribrí graves offered by early 20th-century observer Thomas Joyce (1916, 105), who describes their construction as being 'in the form of a penthouse' in opposition to the flat grave caps favoured by another indigenous group, the Cabeçar.

The uppermost end of the angled dacite slab of the intact KOT-F unit grave was supported with large, unworked stones similar to those available in any Boquete stream bed. Many small stone chips were used as chinking stones in between the larger stones. Burial cavities of roughly 0.5 × 2m were excavated into the hard yellow clay and ash substrate. Grave goods were found throughout the burial cavity, but tended to be closer to the lower edge of the angled dacite slab. Radiocarbon samples from the grave in the KOT-F unit date it to roughly AD 1300 (ß 204731: 680 ± 40 BP; ß 204732: 600 ± 40 BP).

Figure 44: Cache of KOT-F grave goods in situ

Figure 45: Ceramic sherd found near the KOT-F grave

Figure 46: Ceramic whistle found near the KOT-F grave

Figure 47: Zoomorphic ceramic vessel found near the KOT-F grave

A total of ten complete or nearly complete ceramic vessels were associated with the grave in the KOT-F unit [Grave goods from the intact grave at BE-16-KH]. This seems to be a fairly well-provisioned grave relative to Barú area standards. While Swedish archaeologist Sigvald Linné (1936, 97) stated that a prolific Czech-born looter, Louis Hartman, found as many as 30 vessels in a single grave in exceptional cases, a representative of the Gothenburg Ethnographical Museum, Henry Wassén (1949, 241, ![]() ) noted an average of only two ceramic vessels per grave and a significant percentage (38%) of graves with no ceramic vessels at all in his sample of 117 graves.

) noted an average of only two ceramic vessels per grave and a significant percentage (38%) of graves with no ceramic vessels at all in his sample of 117 graves.

The notorious 19th-century grave exploiter, J.A. McNeil, correctly believed that dacite slabs and basalt columns used in grave construction were transported great distances from their original quarry area (Holmes 1887, 7, ![]() ; 1888, 20). The source of basalt columns in the Boquete area is well known, as it is a local landmark adjacent to the municipal water source, while the assumed source for the dacite slabs was provided by geologist Robert Terry to Swedish archaeologist Henry Wassén (1949

; 1888, 20). The source of basalt columns in the Boquete area is well known, as it is a local landmark adjacent to the municipal water source, while the assumed source for the dacite slabs was provided by geologist Robert Terry to Swedish archaeologist Henry Wassén (1949 ![]() ).

).

Figure 48: Map of the quarry locations for the basalt columns and dacite slabs in relation to the BE-16-KH KOT cemetery with least-cost paths (by slope)

Figures 49-51: The basalt column quarry site in Boquete, Panamá

As local boulders and cobbles from nearby stream beds are readily accessible to the cemetery and require comparatively little effort for transport, the decision to quarry and transport these distinctively shaped volcanic stones over far longer distances shows the grave diggers attributed a form of 'value' to them that did not continue into the present, or at least not to the period of the 19th-century 'gold rush'.

The comments facility has now been turned off.

| The portability of Nature is extremely interesting. In Iceland we tend to think about volcanic ash only as a dating method (tephrochonology) or as a hindrance (with the recent eruption of Eyjafjallajokul). What is interesting in connection with Karen's work here is the other uses of volcanoes, and in particular their telluric properties.

In one way or another, through long term geological processes, the products of volcanic activity end their way as important sources for both the material and spiritual in contemporary life; the rare materials that are in our phones and computers; the raw materials for our houses etc. There is therefore no reason why the products of more recently active volcanoes can not have a similar significance in the lives of those in the historic or more recent pasts. There is also a tendency to view volcanic activity in a negative way, as a destroyer of crops, grazing areas for livestock, and the radical transformation of habitable land into desert. While these negative associations are very real they are also over played, and the positive aspects of volcanic activity are rarely represented. Volcanoes have value, and this is not only about power, but also in their symbolic meanings and in their practical uses. Volcanoes are not just time machines or negativities that impinge on society, but provide plenty of positives and opportunities for contemporary society and in our understanding of the complex myriad of relationships between humans and their non-human partners in the past. | Oscar Aldred |

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s)

University of York legal statements | Terms and Conditions

| File last updated: Mon Oct 11 2010