Figure 10: Iconoclasm at Fowlis Easter: the broken faces of a medieval ambry. In most contexts, the ambry itself would not have survived iconoclasm. In this case the faces appear to have been intentionally removed, and later replaced.

Second Commandment: 'Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth (Exodus 20).' Discussed by Calvin (1975 [1536], 19-21).

The physicality of iconoclasm is often overlooked in favour of its ideological significance. In early attacks the Church's most treasured objects were removed in frenzies of destruction; statues defaced, relics smashed, images burned, fittings torn out (Fig. 10; Aston 2003). However, even organised iconoclasm was destructive. After a series of attacks it still took almost a year to adapt St Giles, Edinburgh, for Reformed worship (Spicer 2003, 34). Workers toiled to eradicate the medieval; beating, cutting, smashing, peeling, the rhythm of their movements, the sounds of destruction and construction filling the air for months on end. After much hammering and sawing, new seats and stools replaced the medieval multi-focal array, focusing worship around an imposing pulpit. On small rectangular churches large transecting extensions were built, one brick at a time, giving rise to the distinctive T-plan kirk (Figs 11 and 12; Hay 1957, 18-35). Nothing was to detract from the Word. Everything had to be repainted. At St Giles, Edinburgh, the words 'this is ye place appoyntit for publik repentance' were even painted onto a pillar (Spicer 2003, 34).

Figure 10: Iconoclasm at Fowlis Easter: the broken faces of a medieval ambry. In most contexts, the ambry itself would not have survived iconoclasm. In this case the faces appear to have been intentionally removed, and later replaced.

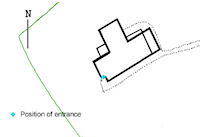

Figure 11: Plan of T-plan church at Eckford, Scottish Borders. A very common kirk type, in the T-plan, unlike in a medieval church, there is only one focal point occupied by the pulpit and the penitent at its foot (jougs attached to the exterior of this church, D8).

Figure 12: Interior views at Spott T-plan church focusing upon the pulpit. (jougs attached to the exterior of this church, D9).

Today some see iconoclasm as a move towards drabness (Yates 2008, 64); others towards the supremacy of the word over other communicative forms such as art (Todd 2002, 328-9); still others identify cases of the incorporation of secular art into the church, seeing it as a move, ultimately, towards secularism (Hay 1957, 215). The common denominator is that, in variable ways, all testify to the eradication of the medieval world's sensual religious mnemonic devices and a restructuring of the visual world (Spyer 2006, 127). Kirk session records and rare survivals show, however, that this restructuring was not rapid. Even in the 1640s elders across the country were finding forbidden images and crucifixes in homes and kirks, including those of ardent Protestants (Todd 2002, 330-1; Aston 2003, 20). The Gray family of Fowlis Easter were among the first high-ranking Scots to be outward proponents of the Reformation. Yet as late as 1616 they were being regularly chastised by the Synod for failure to paint over the medieval art that adorned their rood loft (Fig. 13; Dalgetty 1933, 22, 69). This testifies to a broad spectrum of experiences of reform, from those of zealous iconoclasts, to Protestants with secret pictures and crucifixes, to those who did not accept reformed doctrine at all.

When considering the changing mnemonic devices of reform, scholarship inevitably focuses upon the physical presence or absence of features: memory itself is frequently overlooked (e.g. Hay 1957; Aston 2003; Spicer 2003). Churches could be littered with broken bits of their medieval antecedents (Fig. 10); however, even in their absence people still knew what lay under painted walls. Worshipping in a whitewashed church, from a historical perspective, may seem to give primacy to the Word (Aston 2003), but this overlooks the fact powerful memories endured for generations. Those who saw themselves as having zealously repainted for the Lord had to worship with heretics who sneaked images home; equally, those who tried to save a precious legacy continued to worship with the heretics who tore it down. The white church, under the watchful eye of the pulpit, rather than offer a foretaste of heaven, may have been more akin to a foretaste of hell. To the early reformed Scot, the destruction of iconoclasm could be interpreted as a metaphor, or even a portent, for the impending end of the world. Rebuilding over the old may have erased it. Alternatively, however, it may have served as a reminder of the thin barrier between salvation and oblivion and hinted at the polluting power of sin which could underlie even the most outwardly innocuous exterior; a neighbour, a friend, even a spouse.

Complex, contested and multi-faceted, the early reformed kirk was more than a neutral backdrop to discipline culture: it was an integral part of both the everyday and the spectacle elements of performing discipline. Bucer's vision of church discipline was that its purpose was to educate penitents about their sinfulness and thus to increase the penitent's gratitude to God (Burnett 1991, 453-5). In order to experience gratitude, the sinner had to know what they were being saved from; they had to understand the consequences of sin and damnation. In this respect, even without the art of the medieval, the kirk itself could have been a part of the powerful arsenal of ecclesiastical discipline. With uneasily white walls that obscured a now forbidden past, words, and material culture, a cohesive message could be conveyed, both to the penitent and to the community, of the perils of sin and the need to repent.

Choose your own | Repentance Stool | The Body of Shame | A Changing World

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s)

University of York legal statements | Terms and Conditions

| File last updated: Thu May 26 2011