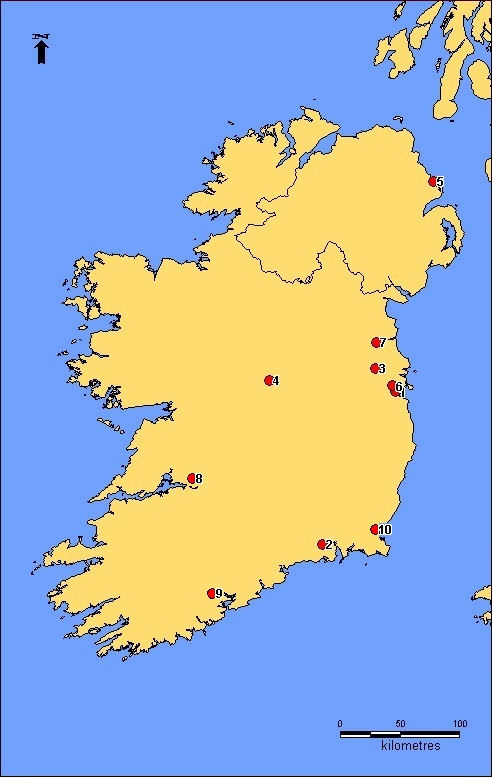

Though our knowledge of combs from England's Irish Sea coast is minimal, the situation in Ireland itself is rather more satisfactory. The large corpus from Dublin awaits publication, but a number of combs held by the Royal Irish Academy have been catalogued by Wilde (1861), and the Irish corpus excavated prior to the last third of the 20th century was helpfully synthesised by Dunlevy (1969; 1988). More recently, large numbers of excavations have taken place ahead of development across Ireland. Combs are thus known from a number of ringforts and rural sites (including duns, crannogs, cashels, raths and souterrains, e.g. Dun Ailinne; Newtonlow, Moynagh Lough; Slugarry; Ballyegan; Cormac's Chapel; Colp Cross; Ballyvass), churches, cemeteries and monastic settlements (Mount Offaly, Cabinteely; Clonmacnoise; Insichaltra; Templedriney; Lurgoe; Ardfert) , urban excavations (Waterford; Wexford; Dublin; Cork; Trim; Galway; Belfast), castles (Rock of Dunamase; Athenry) and multi-period sites (Ninch, Laytown; Killegland, Ashebourne). It is not possible to discuss these finds in detail here, but key sites are discussed in O'Sullivan et al. 2008, and the Irish comb corpus itself will be synthesised in detail elsewhere.

However, some general comments on the Irish collection are appropriate. Combs include representatives of Types 1b, 1c, 10, and 11, as well as 5, 6, 7, 8a, 8b, 8c, 13, and 14b. As discussed above, the status of Type 12 is rather ambiguous, but it certainly does not seem to have been important in pre-Viking or Viking-Age Ireland. Interestingly, Type 9 seems to be poorly represented; none of Dunlevy's descriptions or illustrations fit the type, while the majority of combs in the Irish collections have iron or bone rivets (I. Riddler pers. comm.).

When this collection is broken down chronologically, a number of interesting patterns become apparent. Settlement in Early Christian Ireland is characterised by a number of distinctive site types, including the range of structures often collectively referred to as ringforts (Stout 1997). However, it is another form of site - the crannog - that arguably provides the greatest insight into comb use in the pre-Viking period, and it is germane to briefly discuss the collections from some key examples.

Though Ireland has a long (if punctuated) history of crannog construction and use, the high point seems to have been between the 6th and 11th centuries (see Baillie 1985 and Lynn 1983; c.f. Crone 2000; O'Sullivan et al. 2008, 80-1), and their comb collections tend to comprise fragments of Types 1b, 1c, and 11. Good examples are known from Ardakillin (Dunlevy 1988, 376, 384, 386, 393), Ballinderry No. 1 (Hencken 1936) and No. 2 (Hencken 1942), and Lough Gara (Campbell 2001, 287; Dunlevy 1988, 382, 389; Fredengren 2002, fig. 63). In contrast, Type 12 combs appear to be unknown (see above). At the site of the royal crannog at Lagore, preservation was very good, and a relatively large number of combs survive, including examples of Types 1b and 1c, while Type 11 is particularly well represented. There is also one possible example of a Type 13 comb with double connecting plates. There are, however, only a few (Dunlevy lists nine) examples of Types 5-8 at Lagore (Edwards 1990, 84-85, fig. 37; Hencken 1950).

As for the Viking Age and medieval periods, the most well-recorded and understood material comes from urban excavation, chiefly from Cork (Cleary and Hurley 2003; Cleary et al. 1997), Limerick (Nenk et al. 1991, no. 357), Waterford (Hurley and Scully 1997), Wexford (Bourke 1990; 1995) and, in greatest numbers of all, Dublin (O'Riordáin 1976; Simpson 2000; Walsh 1997). Irish rural settlement in the Viking-Age is much less well studied (see Wallace 1992, 35). It thus serves us well to consider the comb corpus from Ireland on a general level, before focusing in more detail on the material from some of the key urban sites.

Taking Ireland as a whole, Dunlevy lists fifteen examples of Type 5, from sites such as the High Street, Dublin, and the crannogs at Lagore and Strokestown. Few of these combs come from dateable contexts, but one from the High Street was found in a 10th-century level (Dunlevy 1988, 363). One might note the absence of references to combs in accounts of the cemeteries at Islandbridge and Kilmainham (O'Brien 1998), as well as in Harrison's (2001) discussion of Irish furnished burials, though this might relate to antiquarian methods of collection and curation. Nonetheless, combs are rare finds in Ireland's Viking-Age graves, notwithstanding exceptions at Larne (Fanning 1970) and Finglas (Sikora 2010, 406, fig. 38.3).

Ireland's largest collection of combs from the Viking Age onwards comes from Dublin. Well-dated Viking-Age combs from elsewhere in Ireland are relatively scarce, and Dunlevy (1988, 364) has noted the rarity of class F2 short (Type 6) combs outside of Dublin. One might expect Ireland's other early medieval towns to provide some useful material. However, while the last 25 years have uncovered important evidence of medieval urban development at Cork (particularly in the area around South Main Street), Waterford (particularly along Peter St), and Wexford (Bride Street), as well as Limerick (St John's Castle), there remains an absence of evidence for activity prior to the late 11th century. Results from Limerick are yet to be published in detail, while at the time of writing, the earliest excavated layers at Cork appear to date no earlier than the late 11th century (see Hurley 2010, 154). At Wexford, combs and other artefacts are known from structures that may date back to the 1000s, though the latter half of the 11th century or the 12th seems most likely. Neither have early Viking-Age deposits been identified at Waterford, though we await full publication of the settlement at nearby Woodstown, where part of the sequence appears to pre-date the earliest phases excavated at Waterford itself. Nonetheless, in Waterford city, excavation of late 11th- to 13th-century levels has yielded 81 combs. These combs showed a remarkable homogeneity, with 52 combs fitting well into Type 8c, and another 20 sharing some characteristics with both this type and Type 7. There were also four double-sided Type 13 combs, including some with straight and biconvex endplates (Hurley and Scully 1997, fig. 17:1 no. 15, fig. 17:2, no. 21). Publication of sites recently excavated ahead of commercial development is keenly awaited, as is the important collection from Knowth. While we await publication of so many key sites, it would be imprudent to attempt to synthesise published data as it stands, and the approach taken here is, via a case study, simply to review the material in print relating to key early excavations in Dublin.

The comments facility has now been turned off.

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s)

University of York legal statements | Terms and Conditions

| File last updated: Tue Sep 20 2011