Seren Griffiths

Faculty of Humanities, Languages and Social Science, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK. S.Griffiths@mmu.ac.uk

Cite this as: Griffiths, S. (2015) Peer Comment, Internet Archaeology 39. http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.39.3.com1

The paper by Tong et al. provides a timely assessment of the role that vlogging can play in research excavations, as a form of public archaeology. I was particularly struck by three points.

Firstly, the paper rightfully emphasises the importance of digital media as aspects of public archaeological programmes, which incorporate a range of media. Archaeologists, as inherently interested in the multi-media remnants of the past, should be the first to recognise the multiplicity of approaches both for allowing people to find us, and as a means to get our message across. By this I don't just mean media as ways of satisfying the intrinsic impact statements that are associated within university archaeology, or for project publicity within commercial archaeology. I mean the message that we should all be pitching. That archaeology is a good and estimable thing in itself; as people form attachments to their national collections of fine art or natural history, so too they have a right to be engaged with the historic environment, and we should be unashamed to promote this as an intrinsically good thing.

Secondly, the paper emphasised the importance of having a concept of the design and aims of the digital engagement strategy in advance. Having visited the Bristol University Berkeley Castle project, I am aware of how involved and resource-heavy digital public archaeology work can be. I was impressed by the emphasis on this in a much smaller scale excavation (with, one presumes, proportionally smaller resources) at Project Eliseg. As this paper notes, arguably the success associated with digital public archaeology is directly proportional to a time-on-task approach, for a small team this presents a raft of logistical issues.

Thirdly, I was struck by one of the observations in the open review by Ben Marwick. Marwick states that part of one of the vlogs was unclear to him and others "… especially by viewers who are not familiar with popular depictions of archaeological fieldwork on British television." This for me emphasised one of the immediate challenges in a post-and-respond world, where an offensive comment or ill-thought out remark can result in an individual's censure by a global audience. The challenges and strengths of the web are one and the same. As archaeologists, the audience that we are used to engaging with on open days, in local societies, in lecture theatres, in museums and so on, are not the audiences our vlogs will (we hope) garner. There are risks with a potentially global audience — that we offend through clashes of culture, and that our intentions are misconceived. How then to play, to point and to dig live on the world wide web? As archaeologists we might be expected to be particularly concerned with cross-cultural differences. One of the best aspects of international archaeological conferences is the common understandings achieved (despite different languages) through the lingua franca of archaeology. Differences in practice and research emphasis for example can be acknowledged, but the wider discourse is about doing better collectively, or enjoying other people's discoveries, successes and findings. I think because of the almost inevitable problems of communication on an international platform, we have to accept errors in translation, and try and do our best to be responsible, thoughtful and engaged archaeologists, and move on. Part of this includes asking people to come and work with us on all aspects of archaeological research from project planning, through to fieldwork, and post excavation analysis. Public archaeology does not begin and end with the trowel edge. But part of this also includes actively taking our message out of universities, commercial archaeological units and museums, and out of the narrow confines of field practice. Part of this means taking our message to as many folk as will hear us. To my mind vlogs provide one of a range of ways in which we can do this.

Capturing Biographical Trajectories of Early Medieval Sculpture, Eliseg in Context

Mark A. Hall

History Officer, Perth Museum and Art Gallery, Scotland, UK. mahall@pkc.gov.uk

Cite this as: Hall, M.A. (2015) Peer Comment: Capturing Biographical Trajectories of Early Medieval Sculpture, Eliseg in Context, Internet Archaeology 39. http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.39.3.com2

I am pleased to have the opportunity to comment on Tong et al.'s thoughtful piece of reflection on the vlogging aspect of the archaeological re-evaluation of the Pillar of Eliseg. It impresses in its honesty and its refusal to shy-away from the problems that the vlogging brought into the open, particularly in terms of resourcing and output sustainability, community engagement issues and perhaps undue sensitivity around human remains issues (something that the public likes to and are entitled to engage with, and with due sensitivity). The paper is fully aware of these issues and I would like to focus not on these, nor on the wider vlogging context so cogently assessed by Ben Marwick's review of the paper, but on the underpinning aspect of the cultural biography of, in particular, medieval monuments and objects: the stuff of human lives and how it changes and is changed by the entanglements with individuals and communities (Hoskins 1998; Gosden and Marshall 1999; Hodder 2013).

The Eliseg vlogs certainly deserve recognition for their contribution to the biography of their subject. In a way that traditional academic publication of fieldwork rarely achieves, the video and other blogging around archaeological projects captures both the fluidity of meaning-making and the diversity of understandings by archaeologists, visitors and communities and also by artists engaged to provide alternative access routes for those communities and visitors. The Eliseg Project is relatively recent but even since then there has been a huge increase in the number of video blogs in archaeology, covering not just fieldwork but lectures, conferences and community involvement (see for example Doug's Archaeology for a selection).

The biographical approach to material culture foregrounds the whole trajectory of an object's story as part of an emphasis of an object or monument's continuing relevance and impact. In doing so it can be seen as suggesting a continuous relevance for a particular object or monument. Such an assumed background of continuing relevance can have the effect of washing over the often frequent lacunae in the story of an object or monument. It is very difficult to write engagingly about banality and seeming lack of interest, revealing outcomes that certainly do not fit with the criteria of social engagement that underpins much funding of humanities research. Tong et al. do the subject a great service in making these issues transparent.

On a personal level, I have had a relationship with the Pillar of Eliseg since my teenage years. Born and raised in Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, it was common practice for the Hall family, like so many Potteries families, to take our holidays in North Wales (generally alternating with Blackpool on the Lancashire coast). One of the principal routes we took into North Wales was via Llangollen and the Horseshoe Pass. This gave me an early and enduring engagement with the Pillar and also the adjacent Valle Crucis Abbey and the near-by Dinas Bran castle. The Pillar, it seemed to me, exuded an enigma that both appealed and frustrated (and was entangled with influences including costume/historical film epics and reading The Lord of the Rings) and which set me on a path that I am still exploring. In post-university adulthood my interest in the Pillar was affirmed by the realisation of its significance as an early medieval monument redolent of Welsh identity and demonstrative of the value of text as material culture. At a perhaps sub-conscious level the Pillar became a fixed point in my interior landscape of Britain, and one by which I measured my understanding of other monuments, including my own, initial collaborative application of cultural biography to Pictish monumental sculpture, with the survey of the Crieff Burgh Cross (Hall et al. 2000, including a direct comparison with Eliseg to shed light on Crieff's lost inscribed panel, by Katherine Forsyth). The Pillar's continuing relevance is maintained by its social trajectory, which makes it such a compelling example of a monument with a biography (Edwards 2009) or trajectory (Hahn and Weiss 2013). With this back history then it was something of a major revelation for me that both the vlogging element of the Project and the wider Project itself revealed an apparent disinterest, even apathy, on the part of some of the local community in response to learning about the investigation of the Pillar and its mound. This is certainly in marked contrast to, for example, the work done around the Hilton of Cadboll cross-slab, Easter Ross, Scotland (Jones 2004; Foster and Jones 2008, 205-284). In some ways comparing Project Eliseg with the Hilton of Cadboll project is unfair, because with the latter project a key element was Jones's detailed engagement with the local community to tease out the intricacies of their social and political entanglement with the Hilton of Cadboll cross-slab. The vlogging aspect of Project Eliseg did not set out to carry out such a detailed investigation but did include a useful interview with Suzanne Evans about the results of her undergraduate dissertation exploring local engagement issues (Table 1, Vlog day 4).

Although the project lacked the resources to pursue this (and so left unmined a deeper strata on the articulation of memory) and was a little hampered by its own, understandable decision not to get visitors to contribute to the vlogging, nevertheless it did eloquently demonstrate that there was more to do in this area. It needs no leap of imagination to realise that a follow-on vlogging project centred on the community and how its perceptions may have changed in the wake of Project Eliseg recommends itself. The evident opportunities for drama around the Pillar's biographical episodes readily cries out as a key strand to any such future vlogging, bringing together local schools, adults and the archaeological team.

Project Eliseg and its vlogging has succinctly revealed something of the reality of those dis-continuous lacunae in the biographical trajectories of monuments and through exposing — that is bringing into a wider light — such a lacuna, confirmed that archaeology can open dialogues with and within communities that have the potential to help renew and revitalise a community's story-telling about itself through its past explored today. This is no easy task: both Project Eliseg and the Hilton of Cadboll project demonstrate that communities can be distrustful of the motives of archaeologists coming into re-shape fixtures in their landscapes. When a community appears to disengage from such activity, as was expressed during Project Eliseg, there is clearly an element of rejecting such change, a sharp contrast with, for example, the high level of community engagement attained by the Lyminge Archaeological Project, Kent, England and captured by its project blogs. Project Eliseg's vlogging laid down some commendable, thoughtful groundwork that informs the Pillar's, and so the community's, biography and plants some fruitful seeds for others to nurture.

References

Edwards, N. 2009 'Rethinking the Pillar of Eliseg', The Antiquaries Journal 89, 143-77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003581509000018

Foster, S.M. and Jones S. 2008 'Recovering the biography of the Hilton of Cadboll cross-slab' in H. James, I. Henderson, S. Foster and S. Jones (eds) A Fragmented Masterpiece. Recovering the Biography of the Hilton of Cadboll Pictish Cross-slab, Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 205-284.

Gosden, C. and Marshall, Y. 1999 'The cultural biography of objects' in Y. Marshall and C. Gosden (eds) The Cultural Biography of Objects, World Archaeology 31(2) (Oct 1999), 169-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1999.9980439

Hall, M. A., Forsyth, K., Henderson, I., Scott, I., Trench-Jellicoe, R. and Watson, A. 2000 'Of makings and meanings: towards a cultural biography of the Crieff Burgh Cross, Strathearn Perthshire', Tayside and Fife Archaeological Journal 6, 154-88.

Hahn, H. P. and Weiss, H. 2013 'Biographies, travels and itineraries of things' in Hahn, H. P. and Weiss, H. (eds) Mobility, Meaning and the Transformations of Things, Oxford: Oxbow Books. 1-14.

Hodder, I. 2013 Entangled An Archaeology of Relationships Between Humans and Things, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hoskins, J. 1998 Biographical Objects How Objects Tell the Stories of Peoples Lives, London: Routledge.

James, H., Henderson, I., Foster, S. and Jones, S. 2008 A Fragmented Masterpiece: Recovering the Biography of the Hilton of Cadboll Pictish Cross-slab, Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

Jones, S. 2004 Early Medieval Sculpture and the Production of Meaning, Value and Place: The Case of Hilton of Cadboll, Edinburgh: Historic Scotland.

Films, digs and death: a review of the Project Eliseg videos

Ben Marwick

Department of Anthropology, University of Washington, USA. bmarwick@uw.edu

Cite this as: Marwick, B. (2015) Peer Comment: Films, digs and death: a review of the Project Eliseg videos, Internet Archaeology 39. http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.39.3.com3

In this review I evaluate the article by Tong et al. on the use of video of archaeological fieldwork during the Project Eliseg excavations. To understand the context of this study, I briefly survey how video is discussed by archaeologists in blog posts, conference presentations and scholarly articles. I then assess the aims, structure, content and technique of the videos produced by Project Eliseg. Finally, I analyse the strengths and weaknesses of their use of video using a model of public engagement.

1. Uses of Video in Archaeology

To situate the Project Eliseg video project in the context of past uses of video by archaeologists, I used distant reading methods (Jockers 2013; 2014; Moretti 2013) to examine three different venues where archaeologists discuss their work. The three venues include blog posts on the Day of Archaeology blog from 2012 and 2013 (601 blog posts, 186,927 words), abstracts of the last ten years of meetings of the Society of American Archaeology (18,441 abstracts, 1,636,634 words), and the full text of five scholarly archaeology journals hosted on JSTOR (World Archaeology, American Antiquity, Journal of Archaeological Research, Journal of World Prehistory, Journal of Field Archaeology, 5688 articles, 16,358,383 words). These three datasets represent a much wider range of archaeologists and their work than a traditional literature review and allow insights into archaeological activities that are infrequently represented in the scholarly literature. The R code and data to reproduce the results presented here are openly available online. Since a full exploration of this rich dataset is beyond the scope of this review, the open availability of the code and data allows anyone to explore further without any restrictions.

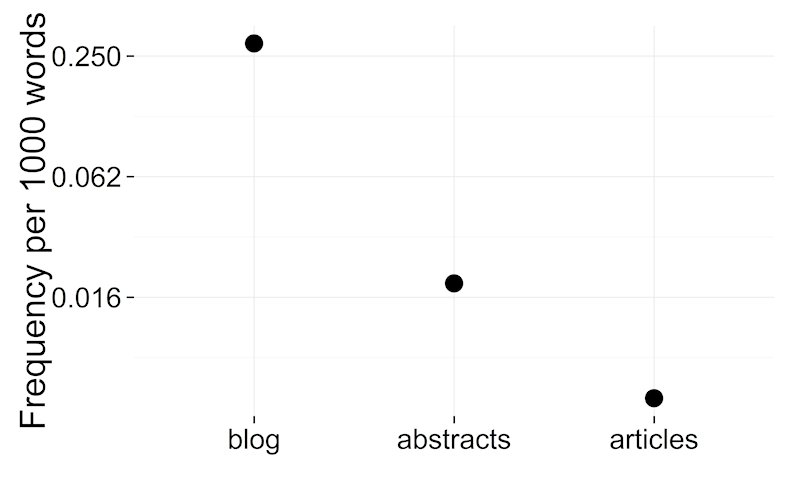

These three corpora are located along a spectrum from informal, public-facing writings on the day of archaeology blog, to short-lived but more professionally focused writing in the conference abstracts, to the enduring scholarly literature written for a specialist audience. In Figure 1 we see that the relative frequency of the word 'video' is substantially higher in the blog posts compared to conference abstracts and journal articles. Looking at words that are strongly correlated with 'video', in Table 1, we see that the blog posts are mostly concerned with practical details of field activities while the abstracts are mostly about professional film and television productions. The highly correlated words in the journal articles are difficult to interpret, probably because most of them are garbled from imperfect optical character recognition of PDF files. To work around this, a k-means clustering method on the journal articles containing the word 'video' revealed four clusters of 38 articles. Two of the clusters contain articles about the use of video for imaging and data collection. The topic of the third cluster is unclear, and the fourth cluster, with only four articles, relates to community heritage management topics. The general impression here is that discussions of video by archaeologists most frequently occur in informal, public-facing writing such as the Day of Archaeology blog, and when they occur in that corpus they are often about fieldwork. At the other end of the spectrum, in the scholarly literature video is mostly discussed as a data collection method, and rarely as a mode of public outreach. These data indicate that the scholarly report on the Project Eliseg video project is unusual and a rare type of contribution to professional archaeological literature.

| blog | abstracts | articles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| word | correlation | word | correlation | word | correlation |

| quarter | 0.56 | anemone | 0.32 | subfiles | 0.45 |

| sections | 0.56 | barbareño | 0.32 | subfile | 0.45 |

| acres | 0.56 | cinematographer | 0.32 | hnousie | 0.45 |

| alberta | 0.56 | erlend | 0.32 | ccxntrol | 0.45 |

| artefacts | 0.56 | filmmaking | 0.32 | anel | 0.45 |

| bifacial | 0.56 | monterrey | 0.32 | naidway | 0.45 |

| Bites | 0.56 | runnerup | 0.32 | orionoftg | 0.45 |

| bonnet | 0.56 | ygnaciode | 0.32 | tirte | 0.45 |

| boulders | 0.56 | film | 0.31 | commorl | 0.45 |

| clothes | 0.56 | television | 0.27 | photograph | 0.45 |

| consulting | 0.56 | covert | 0.24 | mappingand | 0.45 |

| difficult | 0.56 | streaming | 0.24 | ramtek | 0.45 |

| edmonton | 0.56 | atomicage | 0.22 | north-east | 0.45 |

| extends | 0.56 | audio | 0.22 | lcatiomn | 0.45 |

| eyeprotection | 0.56 | bren | 0.22 | stepenoff | 0.45 |

| Eyes | 0.56 | cafés | 0.22 | arget | 0.45 |

| find | 0.56 | detonations | 0.22 | conditioras | 0.45 |

| gaiters | 0.56 | dinnerware | 0.22 | fromx | 0.45 |

| gauge | 0.56 | documentaries | 0.22 | clonamon | 0.45 |

| harness | 0.56 | ernestine | 0.22 | tachpong | 0.45 |

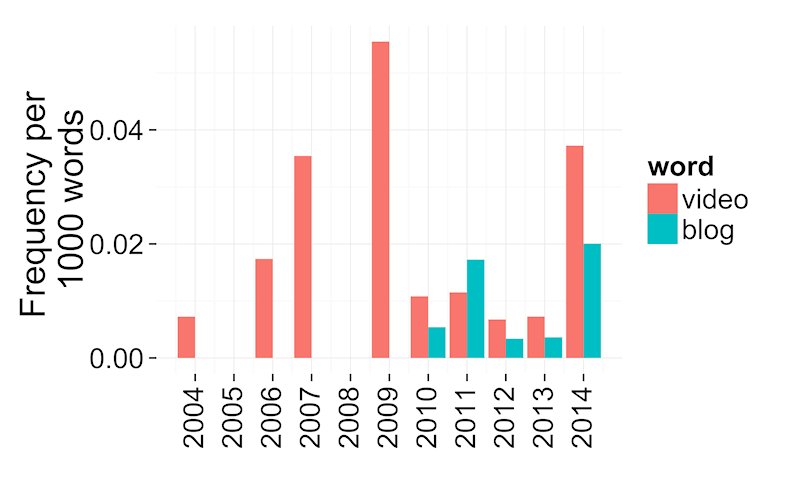

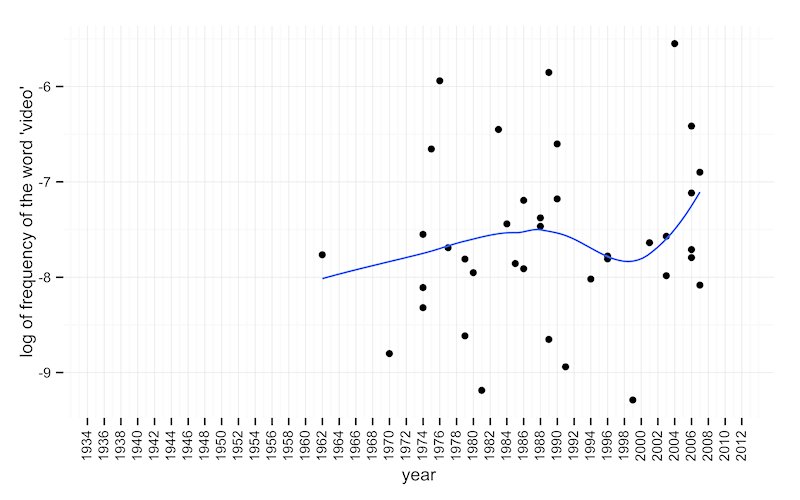

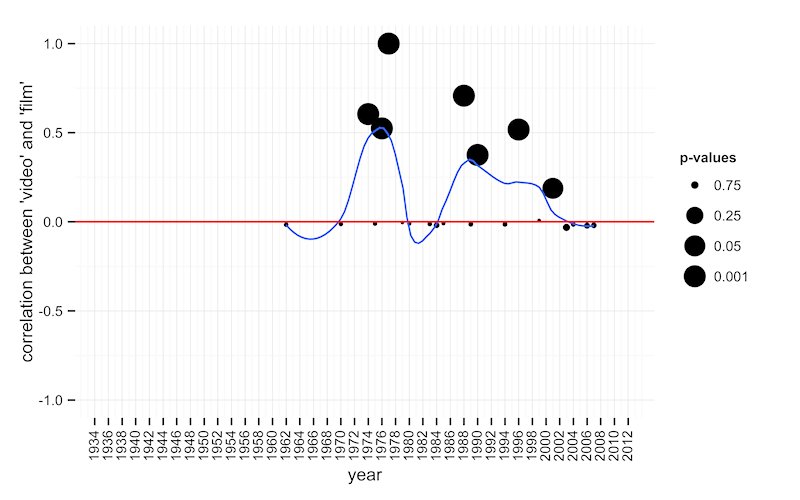

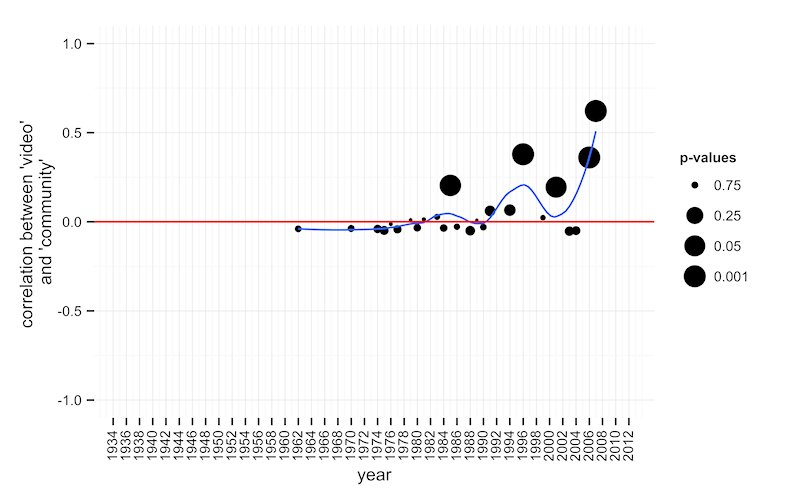

We can get a chronological perspective on discussions of video from the SAA abstracts and the journal articles. In Figure 2 we see that video has been mentioned since 2004, when the PDF files of abstracts first became available, and peak in 2009 when there was a session titled 'It must be true, I saw it in a video', which aimed to examine popular online video and television series to discover and evaluate the messages about archaeology that they transmit to the public. By comparison, blogging only appears in the abstracts for the first time in 2010. In 2014 video was discussed as a tool for data collection during fieldwork, as a technology for archiving field data, and as a method for communication, both to the public via websites and to the professional audience via videos shown during the conference presentations. Among the scholarly articles we see the first mentions of video in the early 1960s, with a slight upward trend towards the present (Figure 3). In Figures 4 and 5 we get an impression of how scholarly discussion of video has changed through time, as the correlation with 'film' decreases while the correlation with 'community' increases over time. This suggests that while scholarly discussions such as that by Tong et al. on the use of film to engage with the wider community are uncommon, they may be becoming increasingly relevant and valued in scholarly publication.

2. The Aims, the Structure, Content and Technique of the Videos

The 30 videos created by or for Project Eliseg represent an excellent effort to go beyond the common methods of public engagement and create an enduring, engaging and visceral record of the field work. The videos complement a diverse outreach platform that includes site visits by school groups, museum displays and talks, media articles, longform blog posts and micro-blogging via Twitter. Such a comprehensive outreach strategy is remarkable and an excellent model for projects of any scale. The substantive archaeological goal of the fieldwork is to investigate the life-history of a medieval stone monument located on a mound in Denbighshire, Wales. The excavations were focused on identifying activity at three specific periods: testing for possible prehistoric origins of the monument, identifying early medieval reuse of the monument in mortuary and commemorative contexts, and identifying traces antiquarian excavations.

The excavation was filmed for two specific reasons. First, to communicate the details of the fieldwork to people who are unable to travel to the location and visit the excavation in person, and second, to capture the field workers' initial and changing interpretations of the archaeological evidence during the moments they encounter it. It is not clear at what point the value of the second aim is extracted. Is the value generated by focusing one's thoughts to speak coherently to a camera, or is the value generated by reviewing the field work video during the post-excavation analysis phase? Perhaps both are implied, but there is no clear strategy for how the videos will be used as an interpretative aid beyond the moment of their creation. Tong et al note that 'Perhaps the greatest benefit was to summarise the end of each field season', suggesting that the process of self-reflection leading up to speaking to the camera was especially valued. This also raises the question whether the post-excavation analysis activities will similarly be recorded by video, which is not addressed here.

The twin purposes of creating the videos indicate two distinct intended audiences: an audience of interested members of the public with little or no specialised knowledge of archaeology, and an audience of archaeologists, perhaps even the same archaeologists who are conducting the excavations. Most of the videos are clearly directed at the public audience, but the videos sometimes switch between these two audiences uneasily. On the one hand, there is some engaging and entertaining general details about the field work that is well suited for public consumption in the Season 3: day 5 video (indeed, this reviewer had hoped that Tong would be in front of the camera more often in the later videos). Similarly, in Season 3: day 9 there is a well-constructed commentary by Kirton on the recording of a cist. This video is confidently narrated and leads the non-expert viewer at a comfortable pace, clearly illustrating the technique of quarter-sectioning and describing the finds of cremated bone and the context of these finds. In the Season 3: day 11 and 12 videos, Robinson similarly gives an accessible description of cist excavation, taking care to define technical terms, with his narration elegantly accompanied by illustrative still images and video.

On the other hand, in the Season 3: day 14 video there is a regrettably short dismissal of the interpretation of a bone pin as a high-status object by Williams. Williams presumes that his viewers may have been misled by unnamed popular television programs to understand the bone pin as a status symbol, an interpretation he rejects without explanation. While this might be a valuable record of the interpretative process for later review by the team, the viewer among the general public is left wondering what the preferred alternative explanation actually is, and an opportunity for a positive and constructive engagement with public understanding of archaeology seems to have been missed. Williams has a complex screen presence, his narrations of the field work are the most substantial and lengthy, and his delivery is highly animated, engaging and well suited for public consumption. One element of his complexity is his use of humour, which is occasionally problematic because although this was intended as a gently mocking reference to popular television programs about archaeology, it may be mistaken for professorial condescension, especially by viewers who are not familiar with popular depictions of archaeological fieldwork on British television. The challenges and risks of using humour in public speaking are well documented, and self-effacing humour, infrequently used by Williams, is regarded as the safest strategy because it creates conversational rapport, makes the speaker seem more approachable, and has no implied superiority of the speaker over the audience (Attardo 2014).

One of the challenges in fulfilling these dual purposes of making the videos is the rapid pace of production. A distinctive characteristic of vlogging, compared to other forms of video capture and production such as documentary making, is that videos are recorded, produced and released on a regular and short schedule. In this case nearly all the videos were captured, edited and uploaded to YouTube within a day. This represents a substantial investment of time, and a remarkable accomplishment for the project videographer, an undergraduate archaeology student who was also working on the project as an archaeologist. This rapid production gives a feeling of real-time reporting and is an impressive fulfilment of the goals of shortening the distance between the excavation location and anyone who wants to learn more about the fieldwork. A wide variety of cinematic techniques are employed in the videos, including subtitles, overlays and annotations, pans, zooms, and varied scene composition and transitions. The effective use of these techniques adds visual interest and appeal to the videos and keeps the viewer engaged. The quality of sound recording is impressive given the basic equipment used and the challenging conditions of high winds and road noise.

A universal limitation of any video is the difficulty of searching for content within a clip. In this case a brief description of each video helps to orient the viewer, but the notes are very brief indeed, and the automatically generated captions on YouTube are comically inaccurate, so the contents of the videos are effectively unsearchable. This could be overcome by a more detailed description for each video, which was presumably prevented by time constraints. The structure of the videos varies widely, with most videos opening with a short introduction, but some do not, and most lack a satisfying conclusion. Given the rapid production schedule, these structural inconsistencies are understandable, but it is worth making a constructive observation that effective video is like effective writing, in that it has an obvious structure, audience and purpose (Hampe 2007). A recurring video structure of a clear introduction, main body (perhaps including something like 'artefact of the day') and clear conclusion would have given more unity to the video collection, and helped generate engagement and recurring viewers.

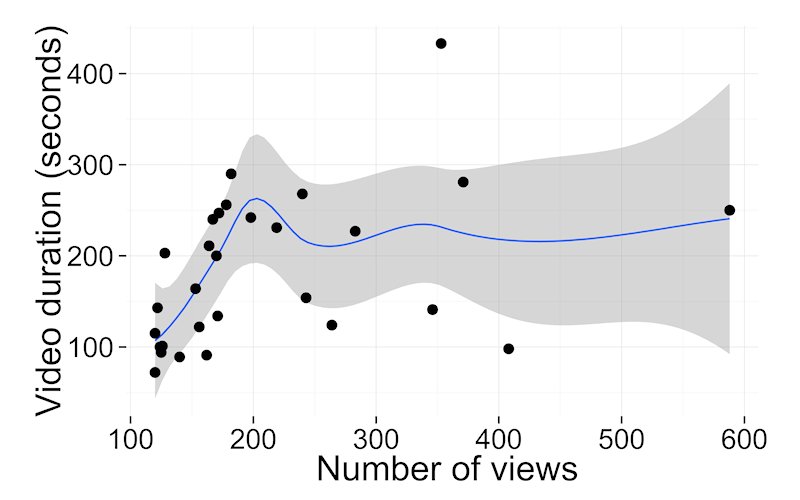

The authors offer a balanced assessment of the reach and engagement that the videos achieved, noting the mixed reactions recorded during ethnographic interviews with local residents to the videos, and the low level of engagement (comments, likes and shares) on the videos on the YouTube website. At the time of writing there were a total of 8,799 views of the entire video collection. Interpreting this value is difficult because YouTube are notoriously secretive about how the views are counted (there is no way to tell the difference between one person watching a video 100 times or if a hundred people are watching the first five seconds of the same single video). In any case, the median view count of 172 supports the claim that the videos were a 'a moderate success' in reaching an audience in a different way to an in-person site visit (there is no information about whether site visitors were not also viewers of the videos). The authors note the wide distribution of view counts on YouTube, with the 35 minute 'Season Two, Pillar of Eliseg Archaeological Excavation' end-of-season video being viewed ten times more than most of the daily videos that are less than five minutes long. While the video analytics have limited interpretative potential and suggest relatively low engagement, there is an interesting relationship between view count and video duration. In Figure 6 we see a positive correlation between view count and video duration, but only up to videos around 250 seconds long (roughly four minutes). For videos longer than four minutes, the relationship disappears, suggesting the constructive observation that this might be the optimum duration for a daily video log of an activity like excavation. These data are consistent with previous findings (Biel and Gatica-Perez 2011; Biel et al. 2011) that four minutes is an ideal time for video blogs.

3. A Model of Public Engagement

Implicit in any strategy of public engagement is a model of how the public understand archaeology, and to interpret the use of video by Project Eliseg I turn to a tripartite model of archaeological understanding based on Abbott's (2004) updating of Charles Morris' (1946) classic theory of semiotic relations (Marwick et al. 2013). The three components are syntactic archaeology, semantic archaeology and pragmatic archaeology. Syntactic archaeology refers to the presentation of archaeology as a set of abstract arguments about prehistoric human life with little tractable value to the public, perhaps uncharitably described by the public as an ivory tower game. Semantic archaeology is a more positive understanding of archaeology as a transposing activity, where a question about the past is moved into the common-sense world of the immediate where it becomes immediately comprehensible. Pragmatic archaeology is archaeology that results in intervention on a current issue of public importance. Because archaeological research rarely encounters a narrow neck of causality (Abbott 2004, 9), the public rarely understand archaeology as a pragmatic activity.

The Project Eliseg videos convey to the public the understanding of syntactic and semantic archaeology. The focus on excavation technique in many of the videos establishes the team as diligent and careful, but represents syntactic archaeology because of the prominence of technical details of the archaeological process. On the other hand, the focus on the cists at the site and the discussion of funerary behaviours and antiquarian excavations in many of the videos conveys a semantic understanding of archaeology. The prehistoric treatment of the dead, and the antiquarian fascination with this are themes prominent in Williams' contributions to the videos, and help to transpose the details of the archaeological record to tractable issues about how the dead were treated and the social meaning of the monument. Tong et al. note that the videos discussing the mortuary contexts were among the most viewed, demonstrating the intensity of public engagement with semantic archaeological understanding.

A pragmatic understanding of archaeology did not appear to be successfully conveyed, with Tong et al. describing apparent indifference from local residents towards the excavation. The authors find evidence that 'death sells' in their videos focused on mortuary dimension having high view counts, but that they were limited in their ability to engage with this theme owing to ethical concerns and the conditions of their Ministry of Justice licence that prevented human remains from appearing on the videos. Given the prominence of death as a research theme for Project Eliseg, a few options for how the videos might have conveyed a more pragmatic understanding of archaeology might be constructively suggested. For example, an interesting addition would have been brief video interviews of the archaeologists reflecting on their personal views on death and treatment of dead bodies, in light of the cists and antiquarian disturbance at the pillar. Going further, visitors to the site might have been filmed in discussion with archaeologists talking about their reactions to seeing how dead people were treated in the past, and invited to make comparisons with modern mortuary practices and places (e.g. active cemeteries). Drawing on connections between observations of the archaeology, which might be unfamiliar to many visitors, and personal reflections on themes relating to death, which is a universal experience, could have been a productive method for engaging the public and potentially changing their thinking about themselves or the landscape of the pillar.

4. Summary

Tong et al. have provided a revealing and balanced report on their use of video for Project Eliseg. They note the 'happenstance' origins of the video project, and this shows in the inconsistent structure of the videos and their honest assessment of their uncertain success with fulfilling the goals of the video project. As they note, their video blog project is one of the first to be reported from an archaeological excavation, so the combination of their videos and their report will become essential source materials for others using this method of documenting their work and communicating with the public. They have shown that archaeologists can self-produce video blogs with relatively simple equipment and under typical field conditions. In this review I have established the rarity of this type of work, critically examined the aims, structure, content and technique of the videos, and made some constructive observations to benefit future archaeological videographers.

Bibliography

Abbott, A.D. 2004 Methods of Discovery: Heuristics for the social sciences, New York: WW Norton and Co.

Attardo, S. (ed) 2014 Encyclopedia of Humor Studies, Chicago: SAGE Publications. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483346175

Biel, J.I. and Gatica-Perez, D. 2011 'Vlogsense: Conversational behavior and social attention in YouTube', ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and Applications (TOMCCAP) 7(1), 33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2037676.2037690

Biel, J.I., Aran, O. and Gatica-Perez, D. 2011 'You Are Known by How You Vlog: Personality Impressions and Nonverbal Behavior in YouTube', Available https://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM11/paper/viewFile/2796/3220

Jockers, M.L. 2013 Macroanalysis: Digital methods and literary history, University of Illinois Press.

Jockers, M.L. 2014 Text Analysis with R for Students of Literature. Quantitative Methods in the Humanities and Social Sciences, Springer.

Hampe, B. 2007 Making Documentary Films and Videos: A practical guide to planning, filming, and editing documentaries, Macmillan.

Marwick, B., Shoocongdej, R., Thongcharoenchaikit, C., Chaisuwan, B., Khowkhiew, C. and Kwak S. 2013 'Hierarchies of engagement and understanding: community engagement during archaeological excavations at Khao Toh Chong rockshelter, Krabi, Thailand' in S. O'Connor (ed) Transcending the Culture-Nature Divide in Cultural Heritage, Terra Australis, ANU E-Press.

Moretti, F. 2013 Distant Reading, Verso.

Morgan, C. and Eve, S. 2012 'DIY and digital archaeology: what are you doing to participate?', World Archaeology 44(4), 521-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2012.741810

Morris, C. 1946 Signs, Language and Behavior, Oxford: Prentice-Hall. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/14607-000

Katy Meyers Emery

Department of Anthropology, Michigan State University, USA. meyersk6@msu.edu

Cite this as: Meyers Emery, K. (2015) Peer Comment, Internet Archaeology 39, http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.39.3.com4

The physical aspect of archaeological fieldwork makes it well suited to the use of video. It can be applicable across a wide variety of audiences whether commercial, such as that done by Time Team, the dissemination and demonstration of methods for academic purposes, or community outreach. Video provides viewers with a hands-on view, provides transparency to the methods and can visibly show the value of the work being completed. Alternatively, blogs are increasingly being used as a supplementary form of sharing information during fieldwork for both community and academic use. They provide an accessible and quickly updated form of outreach, which can be tailored to a specific audience. The combination of both the accessible style, informality and rapid updates of blogs and the visual appeal and access to the archaeological viewpoint through film is a unique method of engaging with the public and the discipline that rightly deserves more exploration.

Tong et al. provide a significant case study in using daily vlogging (video blogging) as an alternative method of recording reflections and updates on fieldwork for the public and archaeologists. As they mention in their article, public engagement was important from the start of Project Eliseg, and they employed a number of tactics to reach out to the public, including the use of vlogging. I especially appreciate their focus on trying to get the local community involved in the excavation and create a deeper connection between them and the monument.

As noted by the authors, vlogs provide a number of benefits over other types of media, including the ability to better convey and highlight interpretations, demonstrate the enthusiasm of the archaeologists, provide interim interpretations and background information, as well as provide an outlet for students to practice their public speaking. In addition to this, I would add that the Project Eliseg blogs also offered transparency to the public through the provision of rationale and interim interpretations. The excavation of local monuments, especially those associated with potential mortuary aspects, can be highly controversial. By providing video interpretations and imagery, the local public can be assured that the project is being completed in a respectful manner that benefits them by adding to the importance and impact of the monument. Another benefit is that videos capture the landscape in a manner that photos and words cannot. Having visited the site in 2013, I can attest to the natural beauty and enormity of the landscape surrounding the Pillar of Eliseg, and how seeing the monument in situ can help better understand its significance.

Another important aspect of providing vlogs in addition to other forms of social media, is that it ensures accessibility to the site. No single form of outreach is going to be accessible to everyone, so it is crucial that we provide multiple forms of engagement through both digital and analog methods. Videos provide direct accessibility into the site, and create more of a connection between viewer and archaeologist than can be achieved with words alone. The enthusiasm of the archaeologists working on Project Eliseg is clearly seen in the video in a manner that isn't as easily gleaned from the text versions. Further, videos may be more accessible to younger audiences who may not be able to travel to the site or don't have the reading level or interest in textual interpretations.

The authors note that one of the major attractions of the project was the potential for human remains and the finding of the cist-grave. However, they also argue that this was deemed a failure for the inability to produce "attractive ancestors" that would appeal more to the public. From my own experience as a mortuary archaeology blogger, I can attest to the public attraction to human remains and funerary sites. However, the inability to find whole skeletal remains at this project isn't a downside- it shows the true nature of archaeological work and provides a counterpoint to the more popular conceptions of what it means to unearth a grave and study human remains. It is important that we don't shift our priorities to focus on what the public perceives that a burial should be (or as they as primarily portrayed in movies and television)- rather, we should be transparent about the types of materials we usually get and how this varies from popular media and conceptions. I don't see this as a failure of the project- but rather a benefit. We should be using the public appeal for mortuary archaeology as a way to draw people into conversations about the reality of working with these types of sites.

Project Eliseg, with both its successes and missteps in vlogging, provides an important baseline, which future projects can reference when looking for methods to communicate with the broader public. There is still much work to be done in this area, and alternative methods of communicating with the public need to be explored further. Given the opportunity, I would have asked the authors to speculate upon how the team of Project Eliseg would proceed in the future with vlogging, and what advice they would have for those who intend to do this type of informal, daily video blogging.

Video offers an alternative to traditional forms of communication, and a potentially more engaging digital method of disseminating daily logs and interpretations from the field. Vlogging can provide a supplementary form of communication and public engagement that may be more appealing and allow better connections with new and different audiences.