Both the head and the body of Statue 55 have been heavily restored. Within the portrait, the entire left upper third of the head, the nose, the right ear and the neck have been replaced, while in the body, the left forearm, left hand, lower right forearm and hand and numerous damaged toga folds have been added and repaired.

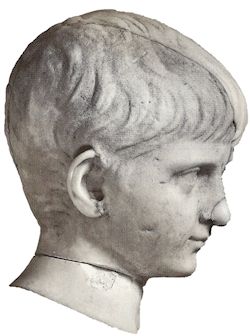

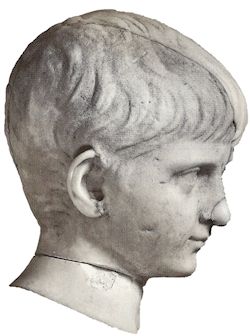

The alterations, additions and modifications to Statue 55 were, until recently, extremely easy to identify (Figure 2). In 1999, however, as part of a wider program of conservation throughout the Petworth collection, the sculpture underwent significant further restoration, the deterioration of 18th-century beeswax and rosin infill having discoloured and shrunk over time (Ingram 1999, 1). During restoration, areas of obvious shrinkage were built up with a mixture of onyx powder, marble flour, trass, beeswax and titanium white pigment applied in melted form using a heated spatula. The finished surface was finally covered with microcrystalline wax dusted with Bath stone dust and trass (Ingram 1999, 2).

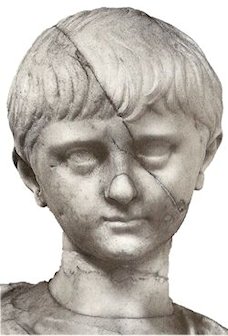

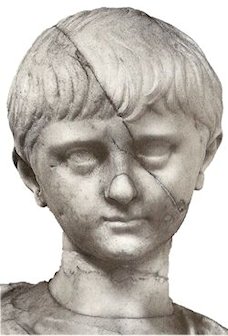

Since the conservation of Statue 55, it is no longer possible to identify where the ancient original ends and 18th century additions begin (Figure 3), something which, as we shall see, has significant ramifications with regard to the perception of identity. While the restoration of badly damaged artworks is eminently justifiable on purely aesthetic grounds, the smoothing over and undetectable infilling of breaks and gaps in the marble has had the unfortunate effect, from an archaeological and art history perspective, of masking the joins and blurring the distinction between ancient and modern, simultaneously fossilising and permanently legitimising aspects of the 18th-century restoration.

Working from pre-1999 photographs, taken by a variety of sources on behalf of the National Trust (including the extensive and detailed photographic survey of the collection conducted in 1987 by Raoul Laev and Gisela Dettloff-Geng: Raeder 2000), it is apparent that the head of Statue 55 had originally been dislocated from its neck with some force, traces of at least two chopping blows previously being visible on the upper right side of the neck, just below the ear and jaw (Raeder 2000, fig. 75). A further blow, possibly with an axe or small-bladed tool such as a chisel, appears to have struck the crown just above the right eye, further fragmenting the image and splitting the head in two, detaching the upper left side. A possible fourth blow may have struck the face just below the left eye on the cheek, creating a deep fracture formerly visible at this point across the bridge of the nose. Additional damage has been sustained to the right ear and tip of the nose, possibly in an unrelated later period of weathering or disturbance while further small-scale evidence of facial battering was formerly evident around the surviving right eye and cheek.

It is not known whether the majority of these recorded injuries to the face of Statue 55 relate to the type of post-mortem memory sanctions enacted upon certain imperial images in antiquity, or to the more radical forms of 18th-century conservation and restoration, whereby areas of damaged or excess marble were cut back in order to better facilitate the insertion of new repairs (Peter Stewart pers. comm. 2013). Sadly, no record was made as to the relative condition and survival of Statue 55, either at the time of its initial discovery, delivery to Petworth or at the point of its restoration.

It is worth pointing out, however, that no other portrait currently housed within the Petworth collection appears to have sustained equivalent levels of damage or abuse to both the head and face. This may suggest that either the individual originally represented in Statue 55 had been especially disliked or that the sculpture as a whole was particularly unlucky at the time of its downfall, interment or subsequent exhumation, suffering considerable amounts of surface trauma in the process.

The head has been substantially restored, probably during conservation work conducted in the later 18th century, the upper left third of the head, the tip of the nose and the right ear having all been replaced. The modern left eye is an exact mirror to the form and position of the right, creating a sense of facial symmetry that may not originally have been evident nor intended in the individual. Both of the new ears are relatively unobtrusive, being tucked back from the face and set very close to the line of the head.

The coiffure, as it appears in the surviving right side of the head, is distinctly Julio-Claudian in form, with well-defined, comma-shaped locks of hair curling behind the ears and down onto the neck where it is combed forwards towards the face. Slight sideburns flick out over the right ear and towards the cheek below the eye. The damaged fringe, as it survives, is low across the forehead and comprises thick strands of hair arranged in parallel curls curving right to left, possibly from an original central parting. It is unfortunate that the upper left side of the face, and the forehead in particular, has been lost, for it is now impossible to re-create the nature of the fringe and coiffure accurately, usually such a prominent badge of identity within the Julio-Claudian family.

The post-1763 restoration has, furthermore, regrettably generated an overtly late 18th-century hairstyle for the replacement left section of the head, with a delicate and decidedly un-Roman, two-layered boyish 'flick' over the inner edge of the right eye. This is a hairdressing effect that does not appear within any portrait of the 1st or 2nd century AD and, with the break between ancient and modern now lost following the 1999 conservation work, compromises the overall integrity of the piece, successfully blurring identity in the process. Interestingly, elaborate bi- and tripartite tufts occur with some frequency within restorations produced by the workshop of 18th-century Italian restorer Bartolomeo Cavaceppi (Fejfer 1997, 4-5), and it is possible that the artistic touches evident here in the hairstyle of Statue 55 are the result of just such a personal quirk.

Where it survives, in the antique, right-hand side portion of the head, the hairstyle of Statue 55 appears similar to the established 'Turin type' (Giroire and Roger 2007, 80), a distinctive coiffure that occurs in the later portrait images of the Emperor Claudius and the earliest ones of his immediate successor, Nero. The Turin-type fringe comprises a delicate triangular fork in the hair, just above the nose or the inner edge of the right eye, the area of portraiture missing from the statue today.

The face of Statue 55 has been extensively cleaned, possibly using a fine chisel, the hair, where it survives, being far more heavily weathered and abraded than areas of exposed skin. Original facial features, evident in the right eye and mouth, are well defined with a small and well-rounded chin. The generally unformed nature of the features, most notably the rounded cheeks and lack of muscle tone, demonstrates that the individual portrayed was in his youth, possibly aged somewhere between ten and fourteen. The mouth is small and fleshy, further emphasising the relatively young age of the subject, lips set in what appears to be a slight pout. The surviving eye is lightly sunken, under a low-arched brow.

The present downward, almost modest, cast of the head and eyes is most unlike the bulk of recorded Roman portraiture, especially those pieces that represent orators, magistrates and other public servants, which usually possess a slightly backward tilt, eyes confidently set over and above the heads of an audience. The 18th-century resetting of the head, originally dislocated just below the level of the jaw, may be a significant contributory factor in the current downward position especially if, as seems likely, the surviving fragment has been repositioned at too acute an angle. The forward-tilting head also seems to be a characteristic feature in certain restorations produced within the Cavaceppi workshop (Fejfer 1997, 4).

In the body, the neck is an entirely new creation, as are the left forearm and hand and the lower half of the right forearm and hand, the two large toes and a number of the more prominent toga folds. Although the body and the surviving portion of head are of slightly different types of Carrerra Marble, it is worth establishing that both pieces are chronologically consistent in style. The surviving area of the face and coiffure indicates manufacture in the latter years of the Julio-Claudian principate while the toga, with its realistic, well-executed drapery, broad folds and delicate pleats, seems to belong to the mid- to second half of the 1st century AD (Giroire and Roger 2007, 80-1, 139) rather than with the narrow and stiffly rendered togas representative of the early 2nd century AD. Both head and body are, furthermore, also in proportion, the chest, arms and feet of the figure belonging to a young adult, broadly consistent with the age of the head, rather than to a more mature individual.

The bodily stance of Statue 55, in declamatory pose, weight on the right leg, arms out with volumen (scroll) in the right hand and capsa (storage case) at the feet, is one adopted by a Roman magistrate or orator, possibly suggesting the responsibilities of adulthood that the young man is about to undertake. It is worth remembering, however, that the left forearm and hand and the lower half of the right forearm with the hand holding the scroll as we see them today are late 18th-century additions, as the original piece may have been missing its arms when first delivered to Petworth (Raeder 2000, 203). The position of the figure, right foot pointed out towards an audience, when combined with both the nature of toga folds and, more importantly, the storage case placed behind (and to one side of) the right leg, suggests, however, that the body of this individual had originally been set in the traditional pose adopted by a Roman magistrate addressing a crowd, and so the restoration, while difficult to fully substantiate, is probably broadly accurate. The absence of a bulla (or pouch to protect the wearer from physical or spiritual harm) around the neck of Statue 55 indicates that the individual represented had reached maturity and is undoubtedly intended to be seen wearing his pure white toga virilis or toga of manhood (Edmondson 2008, 26).