The surviving oak furniture from the medieval and Elizabethan periods is either ecclesiastical or from the upper classes. There is a problem dating vernacular furniture because the same styles were used over a long period of time, and the craftsmen travelled from place to place. This makes it very difficult to ascribe a particular style to different regions. By comparing ecclesiastical furniture with, for example, chairs and stools, it has been possible to suggest regional characteristics from the late 16th century onwards (Elsdon 1981, 5). It has been found that the majority of distinctive vernacular furniture was produced roughly between 1620 and 1720 (ibid, 18).

There was a profusion of decorative motifs to cover long rails or friezes using lunettes, guilloche, gadrooning and arabesques (for definitions see Fleming and Honour 1977, 494; 359; 313; 29). Books of designs were printed, in particular by Hans Vredeman de Vries in Holland (1527-1604) and Johann Jakob Ebelmann in Germany (active 1598-1609). These designs were partly architectural, but were usually of flat patterns easily adapted to carved or inlaid decoration (ibid, 19).

Certain areas adopted particular motifs. Strapwork pattern was popular in Cheshire. The guilloche was used in Westmoreland. Lancashire and Cheshire craftsmen utilised the Celtic motifs of interlace and dragons seen on ancient crosses and in manuscripts (ibid, 19). During the mid-17th century, chairs made in Lancashire and Cheshire commonly have decorations of dragons, tulips, leaves and stylised flowers (Fig. 11) (Chinnery 1979, 481, Temple Newsam 1976). In Gloucestershire, the popular motifs are of leaves and flowers (Temple Newsam 1973, figs 5, 10, 16).

Figure 11 (a-d): Designs of dragons, tulips, leaves and floral

motifs on 17th-century Lancashire oak furniture in the Towneley

Hall Art Gallery and Museums, Burnley Borough Council

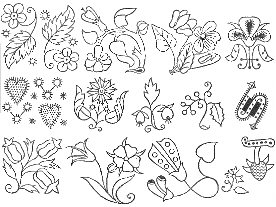

It is suggested that some of the floral motifs seen on Lancashire chairs of the mid-17th century are related to needlework designs (Temple Newsam 1973, figs 21 and 22). Embroidery for use in the home in the Stuart period (1603-1714) is characterised by simple and bold decorative effects. It is mostly of animals and plants. This contrasts with English professional embroidery which copied the continental style of intricate embroidered panels (Connoisseur Period Guides, Stuart Period, 1957, 126). It is only the domestic embroidery that is relevant to this discussion.

Various needlework pattern books were published in London in the early 17th century detailing naturalistic motifs, coiling stems and other related designs (ibid, 128, fig. 1, p.127).

Figure 12: Sheets of designs for needlework from 'A scholehouse for

the needle', published by Richard Shorleyker, London 1624 (after

The Connoisseur Period Guides 1957, 127)

© Internet Archaeology URL: http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue16/1/ch6.33.html

Last updated: Wed Mar 24 2004