Figure 26: An excavated blackhouse at Airigh Mhuillin, South Uist. The byre area with drain is in the foreground whilst the domestic area separated by a partition would have been in the far end. (Symonds 1997)

1 Environmental and Research Background | 2 Post-medieval Buildings | 3 Earlier Vernacular Buildings | 4 Conclusions and Discussion

Descriptions of Hebridean buildings have tended to focus principally on their function (Burgess 1995; Walker and McGregor 1996; Holden et al. 2002). They have failed to address social and cultural aspects related to the organisation and use of space, both to structure, and to reflect, the culture of which they form a part. Clearly, the blackhouse was not only an area for what we might call domestic activities, such as sleeping and eating, but also provided an area for work, by both women and men, and, crucially, a venue for the important socialising necessary to the community. The physical manifestation of these relationships was always limited in the 19th-century Hebridean vernacular since people were relatively poor, although status was expressed subtly in various ways, such as through the display of crockery on the dresser.

Figure 26: An excavated blackhouse at Airigh Mhuillin, South Uist. The byre

area with drain is in the foreground whilst the domestic area separated by a

partition would have been in the far end. (Symonds 1997)

The principal and most obvious spatial distinction in the longhouse was between the byre area, given over to animals and often physically lower, and the upper, domestic, part of the building (Fig. 26). Earlier longhouses tended to have this bipartite division of space although by the late 19th century it became common to have three compartments, the additional room being a sleeping or best room. The manifestation of this division in later buildings included a masonry wall, replacing the timber partitions common in the late 19th century. Prior to this, formal partitions were uncommon in earlier periods since it was said to be bad luck to shut the cattle off from the fire (Thomas 1868, 157). Indeed, early descriptions refer to the division as 'simply a line of rough stones' (Mitchell 1880, 51), and excavation at 39 Arnol uncovered no evidence for a partition in the first, mid 19th-century, phase. In this case, the division was perhaps reflected by the positioning of the box-beds (Holden et al. 2002). Movable timber box-beds replaced an earlier tradition of incorporating stone-corbelled cells in the thickness of the wall as sleeping places. These crubs were described in the earlier buildings of St Kilda, before the rebuilding of the mid 19th century, and were also found in Lewis.

Cattle were the principal signifiers of the crofter's wealth, and, in a culture where pastoralism had been dominant for millennia, they were likely important symbols to the crofter, his family, and their guests (Kissling 1943, 83). This may explain why it was so important to allow the cattle to see the fire (Thomas 1868, 157), traditionally a purifying and sacrosanct symbol used, for example, in the Beltane feast (Martin 1703 cited Bray 1996 20; Prebble 1966).

Branigan and Foster (2002, 131) have argued that the blackhouses of Barra were anomalous in that they did not house the people and the animals. In excavation of five examples, they have found no evidence for cobbling or drains but, rather, have found what they have interpreted as separate byres. This may partly reflect a longstanding cultural difference between the Catholic people of Barra and the Protestant people of Lewis and Harris. However, a brief assessment of the results of their survey work at Ardveenish, Barra (Branigan and Foster 2000, 12-16), shows that there were at least five large longhouses with internal divisions. In another attempt to explain this difference in building size and use, Dodghson (1994, 64; 1996, 189) has suggested that there may be a distinction between those groups that relied on manure for fertiliser and those that relied on seaweed; the former would tend to keep cattle in the house, so that the manure could be easily collected, while the latter would rely more on horses for carting seaweed, perhaps only keeping the cattle in during particularly inclement weather, if at all.

The central fire was permanently lit; indeed, it was unlucky for it to become extinguished (Curwen 1938, 266; Parker Pearson and Richards 1994, 41). The initial ignition of the fire would take place even before the people had moved in to a new house, in order to dry the roof and floor, and drive insects from the thatch. An example at Calanais, Lewis was said not to have been allowed to go out for one hundred years (Curwen 1938, 266). It has also been argued that the fire formed an important part of the maintenance of the building, as it would keep the roof covering, and perhaps the wall infill, relatively dry, thereby increasing its longevity (Walker and McGregor 1996, 31). On Hebridean islands with little peat, such as Tiree, cow and horse dung, turf and seaweed were burnt, and the fires would not have been kept alight all the time (Fenton 1976, 193). Supplementary to the hearth's functional importance as a source of heat, the hearth was the focus of all activity in the household including the preparation of food, eating, evening work, and storytelling. A young member of the family at 42 Arnol described her house in a school essay in 1964:

'During winter, many neighbours come in each night. We form a circle round the fire and discuss many subjects... Very often, after tea, a cailleach [old woman] comes in for a ceilidh [gathering]. You know just to gossip. I remember a few years ago, when my uncle was home from Canada... what times we had, singing... and many other sources of entertainment!'

As such a central feature, the hearth was the place where the oral traditions in song and prose were passed from generation to generation and this can be seen as the antecedent to the current popularity of traditional music. The reverence with which the fire was treated is reflected in the Gaelic translation as aingeal or ainneal, the same as the word for angel (Kissling 1943, 85; http://www.ceantar.org/Dicts/MB2/index.html.) In the evening, before bed, the fire would be partially smothered in a ceremony combining elements of Christian and pre-Christian symbolism, recorded by Carmichael in 1899:

'The embers were evenly spread on the hearth...and formed into a circle. The circle is then divided into three equal sections, a small boss being left in the middle. A peat is laid between each section, each peat touching the boss, which forms a common centre. The first peat is laid down in the name of the God of life, the second the God of peace, the third the God of grace. The circle is then covered over with ashes sufficient to subdue but not extinguish the fire...When the smooring [smothering] operation is complete the woman closes her eyes, stretches her hand, and softly intones in one of the many formulae current for these occasions.' (Carmichael 1928 Vol. 1, 234 cited Kissling 1943, 85)

Spare rooms were unknown and the guests or family members would commonly be accommodated in the barn or byre. This suggests that it is disingenuous to argue that complex and rigid social structures are expressed through what are relatively small spaces in the blackhouse. Rather, it seems that the use of space was multi-functional and open to all members of the household. In contrast to this, early photographs appear to show the mother or father of the household in a seat by the fire – perhaps the most important place (Fig. 27). The single central fire might tend to introduce equality to social interaction, particularly when all ages and genders were sharing social space; although this may have been counteracted by the use of straight benches as seating. Indeed, Thomas mentions specifically that men occupied the bench on one side of the fire and women the bench on the other (1868, 156), a fact reiterated by Childe (1931, 183; 1946, 32) and Kissling (1943, 86). This left/right distinction was counter-balanced by a front/back division on other social occasions (Parker Pearson and Richards 1994, 45). However, it has been argued that the status of the guest was defined in the position offered around the central fireplace, and by its proximity to the most distinguished position directly behind the hearth and facing the entrance (Clarke and Sharples 1985, 70).

Figure 27: Interior of a blackhouse in South Uist, 1934 (Russell 2002, 63).

Photograph by Werner Kissling

Further references to the use of space include the avoidance of windows in the west wall, 'because the sluagh pass by night, and might throw darts within', and the avoidance of throwing water out the doorway after nightfall because the dead 'come to warm themselves there in the smoke' (Murray 1936, 49)

Many work tasks were continued inside the longhouse around the fire. In the summer, however, women would often work outside the house for the better light. There are many illustrations of spinning and knitting, for example, going on outside. Spinning wheels were movable, but larger weaving looms were often permanently set on plinths in the blackhouse, or sometimes in abandoned out-buildings in the early 20th century. Work often continued inside after dark and one lady referred to her preference for the long winter nights of waulking (fulling) cloth, because so much fun could be had by the fire (Mary Martin cited in School of Scottish Studies 1968).

A further element of spatial organisation that may have affected architecture is sun-wise motion, specifically known as deiseal in Gaelic. In 1860 Carmichael recorded the 'consecration' of the cloth after waulking had finished.

'When the women have waulked the cloth, they roll up their web and place it on end in the centre of the frame. They then turn it slowly and deliberately sunwise along the frame saying, with each turn of the web: This is not second clothing, this is not thigged, this is not the property of cleric or priest.' (Carmichael 1994, 600 cited Symonds 1999, 121)

In another example, Margaret Fay Shaw recorded a procession at Hogmanay:

'When they reached the house they walked around it sunwise, chanting Hogmanay ballads or duin.. The torch bearer passed his brand of smouldering sheepskin round the head of the wife..., and then she produced the three round bannocks which the leader of the boys carefully put in his bag and then gave her one in return.' (Fay Shaw 1986, 14)

Other examples of 'sun-wise' movement recorded by Carmichael include the watering of corn, harvesting and the hand grinding of meal (cited Symonds 1999, 121). Excavation in South Uist recorded a stack base that had been laid in a sun-wise motion, and was dated by a Brylcreem tub and oral history to the 1960s, suggesting the importance of sun-wise movement was still respected well into the 20th century (Symonds 1999, 122). Dodghson (1988) has suggested that medieval farming communities in the east and north-east of Scotland may also have incorporated the relation of sun-wise motion to fertility and good luck in their townships. Further detailed analysis of blackhouses may suggest that construction, maintenance and use were influenced by this concept.

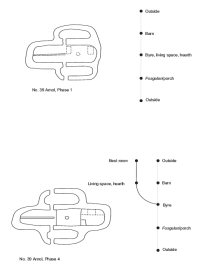

Attempts to understand spatial patterns in the longhouses using access analysis show the buildings to be very limited in their formal hierarchy. This methodology, based on the gamma analysis of Hillier and Hanson (1984), has been applied to Atlantic Iron Age buildings in the Northern Isles (Foster 1986; 1989), and is most clearly explained by Grenville (1997, 17) as an attempt to measure 'the ease of access to and circulation around [and within] a building'. When applied to 39 and 42 Arnol the method produces limited results, although it does show how the introduction of the third private room, coupled with the formalised partitioning of the byre and living area, introduces a considerable degree of complexity to an initially simple and direct layout (Fig. 28). Both the dearth of formal partitions in earlier buildings and the inability of access analysis to address cultural practice mean I have not used this method to analyse earlier structures.

Figure 28: Sketch showing access analysis applied to phases 1 and 4, 39

Arnol, Lewis. Drawn by the author from plans after Holden et al. (2002)

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s)

University of York legal statements | Terms and Conditions

| File last updated: Tues Feb 28 2006