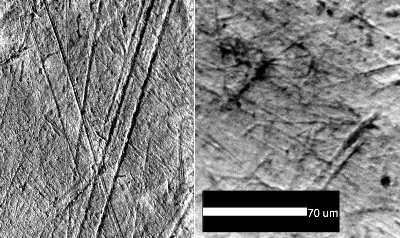

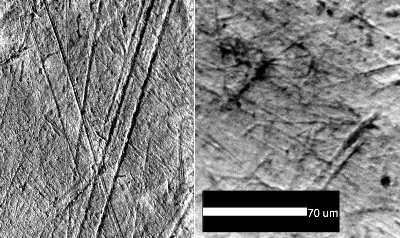

Figure 1: Typical fields of microwear from Aveline's Hole (left) and Oronsay (right)

A number of different proxy methods can be used to investigate what people ate in the past. In the case of the Mesolithic populations of Europe, excavations of sites such as shell middens and settlements provide direct, although limited, evidence for the use of a number of different plant, animal and marine food sources (e.g. Hamilton et al. 1985; Grigson and Mellars 1987; Mithen et al. 2001). Furthermore, analysis of human skeletal material can also provide valuable insight into overall diet among Mesolithic populations, most profitably in the form of dental pathology (diseases of the teeth; i.e. caries, calculus, antemortem tooth loss etc.) (Meiklejohn and Zvelebil 1991) and stable isotope analysis of bone collagen (e.g. Richards and Mellars 1998 ; Schulting and Richards 2001 ). Dental microwear analysis investigates the abrasive content of individual food items, eaten near the time of death, by quantifying microscopic wear features on tooth enamel surfaces. It thus provides insight into different aspects of diet than those evidenced by archaeological, palaeopathological or isotope data and also facilitates a proxy measure of dietary variability when a number of individuals are analyzed from the same site. Dental microwear features form rapidly, so the technique is therefore a proxy measure of short-term diet (Teaford and Lytle 1996).

Figure 1: Typical fields of microwear from Aveline's Hole (left) and Oronsay (right)

Dental microwear manifests as sharply defined pits and scratches on enamel surfaces. Figure 1 shows typical fields of dental microwear from Aveline's Hole and Oronsay respectively. These microwear features form in a distribution of sizes from 0.1µm to 0.5mm across their minor axis (i.e. their width). Therefore, a scanning electron microscope or other instrument capable of resolving such small features is required if microwear is to be measured for quantitative analysis. It is reasonably certain that such microwear features are the direct result of tooth-on-food contact. King et al. (1999) showed experimentally that various taphonomic processes can alter observed dental microwear textures by removing small features. Their experiments also showed that certain burial conditions can damage enamel surfaces, although the damage was visually different from dental microwear. In fact, dental microwear features are only observed on the contact facets where teeth oppose, suggesting it is highly unlikely that they are formed by any taphonomic process.

© Internet Archaeology

URL: http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue22/1/background.html

Last updated: Tues Oct 2 2007