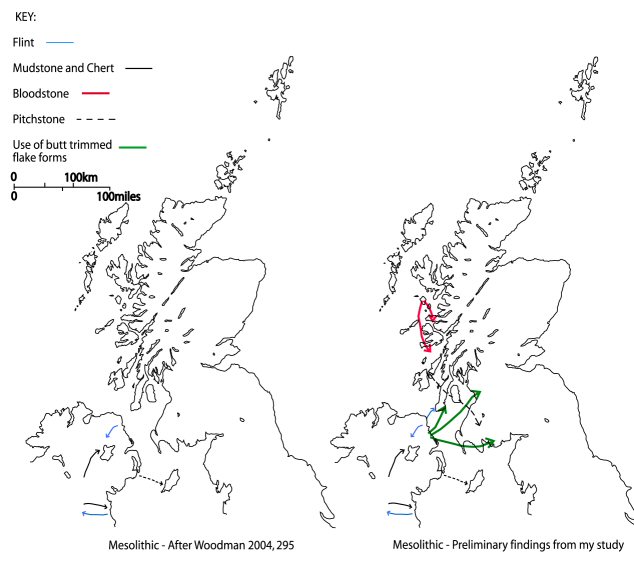

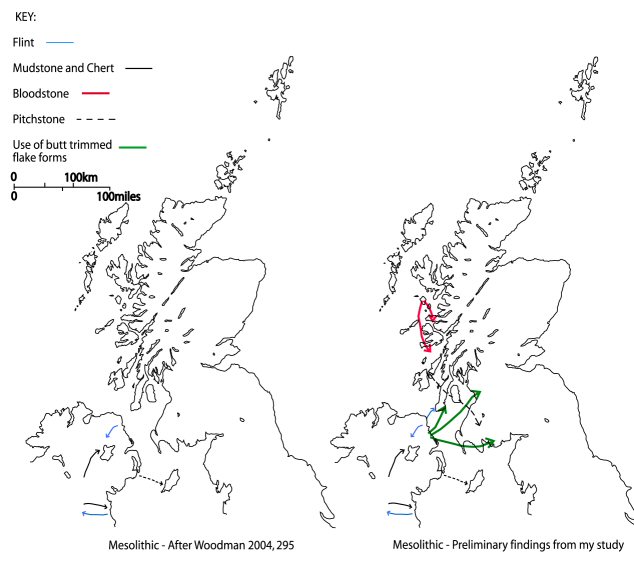

Figure 6: A traditional account of the movement of goods around the area in the Mesolithic (left) (After Woodman 2004, 295) compared to a revised version from the preliminary results of the study (right).

Although this study is still ongoing, the correlation of the information to date has revealed a series of potentially significant trends. In particular it seems the notion that Mesolithic populations in the northern Irish Sea basin were as regionally insular requires a serious reassessment. As discussed, a central tenet of this argument has been the regional differentiation in lithic styles prevalent in the Mesolithic record over the area. Yet by exploring the potential of Mesolithic material culture to fulfil more than simply functional or economic roles we can begin to suggest that an interpretation of such regional differentiation as an indicator for insularity may be an overly simplistic reading of the material. In contrast, as early as the 1980s, a series of discussions have shown that material culture styles have the potential to demonstrate identities, group affiliations and more (reviewed in Conkey 2006). Indeed as Hodder's ethnoarchaeological work in the Lake Baringo area of Kenya illustrated, distinct differences in material culture styles arose amongst groups who were in regular contact but who sought to differentiate group identity by using such different styles (Hodder 1982). The significance of such alternative explanations for differentiation in lithic styles are striking when compared with preliminary results from the study which highlights that there was at least some movement of raw materials and some similarities in lithic styles around the northern Irish Sea basin (Figure 6).

Figure 6: A traditional account of the movement of goods around the area in the Mesolithic (left) (After Woodman 2004, 295) compared to a revised version from the preliminary results of the study (right).

A particularly interesting example is that of the few typically Irish later Mesolithic butt trimmed possible Bann Flake tool forms that have been found in Scotland in Dumfries and Galloway, Ayrshire, and in a small concentration on the Kintyre Peninsula (Cummings and Robinson 2006, 18; Davidson 1948; Lacaille 1945; McCallien and Lacaille 1941; Saville, 1999). Those on the Kintyre Peninsula are particularly interesting and I have argued elsewhere (Cobb 2007) that the presence of these tools is highly significant for a number of reasons. Firstly, the presence of Bann Flake forms represents a clear contrast in practices, but additionally they also represent a clear contrast in the type of social relations elicited by their use. As Finlay has suggested, microliths are composite parts of potentially multiply authored tools and thus through their multiple authorship engender multiply authored identities (Finlay 2003a). In contrast large blade and flake forms such Bann Flakes do not demand multiple authorship in the social relations they elicit, and neither do practices of caching (Finlay 2003a, 2003b). For these tools then to appear in a concentration of sites in Scotland is highly significant. Indeed I have argued that by taking materials from Antrim, and practices and tool types from Antrim and situating them in locations that visually disavow Antrim, these examples used deliberate juxtaposition and contrast (between the materials, practices and ways of being and understanding of the world in two different places) to enable such materials to mutate, transform, and produce new identities and understandings of the world (Cobb 2007). As such the presence of Bann Flake like forms in Scotland may represent more than just a challenge to arguments of regional insularity. Instead it suggests that the deliberate use and situation of these forms in the Scottish landscape enabled those who used them to retain important, multiply authored aspects of personal identity - by re-aligning and enhancing the importance of their ownership of materials and place, by their abstraction from one location and their literal, and visually metaphorical reinsertion, conversion and mutation into another.

© Internet Archaeology

URL: http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue22/6/discussion.html

Last updated: Tues Oct 2 2007