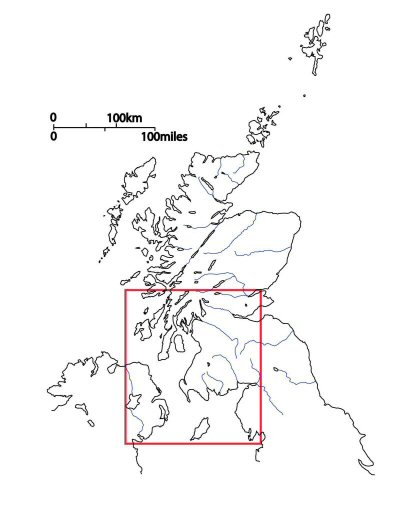

Figure 1: The limits of the study area

Since Richard Bradley's famous observation that "successful farmers have social relations with one another, while hunter-gatherers have ecological relations with hazelnuts" (Bradley 1984, 11), prehistoric hunter-gatherer studies have seen a growing call for a fundamental revision of the main tenets of their study. Indeed in recent years a concerted body of more theoretically interpretive approaches has arisen which has sought to use the growing evidence for the Mesolithic to construct and explore new, richer and more detailed interpretations of the period (e.g. see contributions in Conneller and Warren 2006; also Cobb 2005, 2007, forthcoming a, forthcoming b, forthcoming c; Cobb and Price 2005; Finlay 2000, 2003a, 2003b; Kador 2005, forthcoming; Little 2005; Price 2005, 2007; Young 2000).

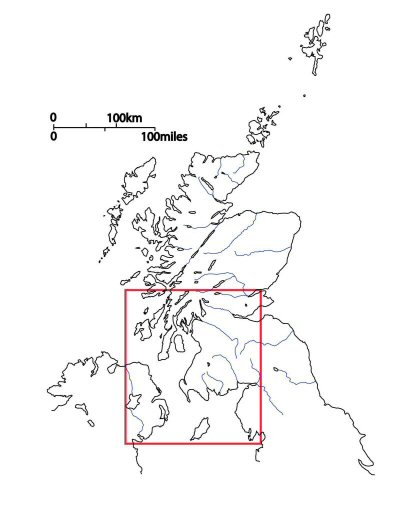

Figure 1: The limits of the study area

My own doctoral research arises from exactly these concerns, and as such in this paper I seek to outline some of the key issues at the heart of this research and the particular problems I see within the study area that this concentrates upon; the northern Irish Sea basin (Figure 1). I will explore how the historic consideration of the Mesolithic in this area, as with the Mesolithic elsewhere, has concentrated largely on interpreting only the environmental and economic elements of prehistoric hunter-gatherer populations, and I will examine how this has led to a series of problematic interpretations. I will also discuss how research agendas in the northern Irish Sea basin have been explicitly driven by modern geo-political boundaries, and I will highlight how this too has led to a potentially limited view of the period in the area. In turn I will illustrate the problematic implications that these two factors have had for the formation of interpretations of the transition from hunting and gathering to farming.

However this is not simply a paper of pure critique and deconstruction, and drawing upon my ongoing research I will discuss the variety of ways I have attempted to address these problematic areas. Consequently I will suggest that we can not only begin to develop new, socially situated interpretations of the Mesolithic period in the northern Irish Sea basin, but that such new approaches can have a fundamental impact upon how we may come to interpret the transition to farming in the area.

An earlier version of this paper was originally delivered at the "Gathering our Thoughts" symposium at the University of York in September 2006, and like the paper presented there, this article represents a reflexive and ongoing dialogue regarding the nature of my doctoral enquiries. As such it is important to stress from the outset that much of this work is subject to change and development and that this paper represents only a summary of my work to date. Many of the notions and case studies it alludes to have been discussed in more detail in press elsewhere (e.g. Cobb 2007, forthcoming a, forthcoming b, forthcoming c), and ultimately the most full discussion of the ideas here will be in my completed doctoral thesis.

© Internet Archaeology

URL: http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue22/6/intro.html

Last updated: Tues Oct 2 2007