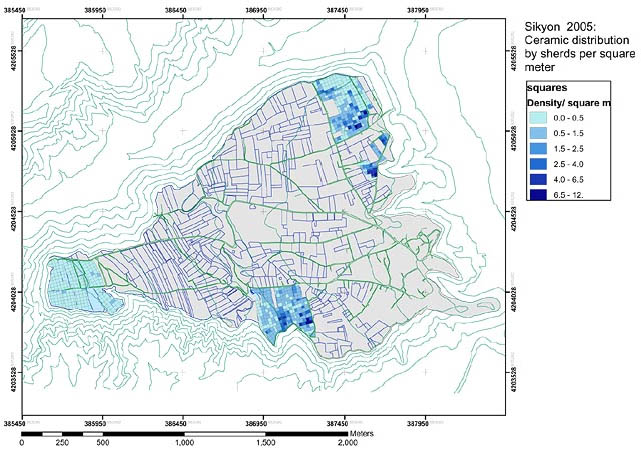

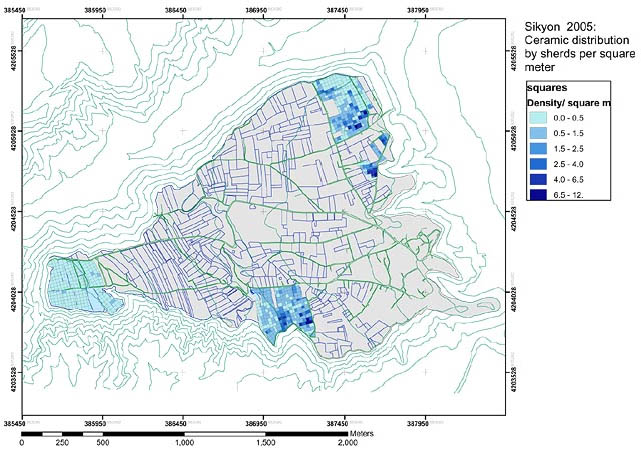

Figure 8: An example of the static maps previously used by the project members. This example shows the ceramic distribution by sherds per square metre.

The Sikyon project has many specific needs, some of which pertain to other archaeological projects regardless of type or location. One such need is for effective collaboration outside the project's data collection phase. Compounding this problem is the distribution of project members around the globe. Even though the project is a Greek one, many key members live and work in other parts of the world. The director works at the University of Thessaly in Volos, which is in the northern part of Greece, while the survey designers and supervisors live in York and Leicester, England. The database manager also lives in York, while the supervisors of the squares are both associated with universities in North America. The pottery specialists are similarly widespread, pursuing post-graduate degrees in the United States, Ireland and Greece, adding to this separation. In addition to the active members of the project, Greece has regional archaeological representatives of the government that are called Ephors. The Ephor for Corinthia, which is the region Sikyon is in, receives regular updates and progress reports for all archaeological work occurring in the area. This close relationship makes the Ephor a de facto member of the project.

All these disparate members demand a certain level of collaboration outside of Sikyon. At the current stage of the project, the pottery people are beginning to compile their notes and synthesise their findings. Other research members anxiously await their conclusions, as they will prove essential for a deeper understanding of the archaeological record. This process does not always happen while at Sikyon but it is essential that their interpretations get to the respective members as soon as they are available. In 2006, for instance, pottery reports were not ready by the time the season was finished. Modern telecommunications enable copies of the reports to be distributed simply and conveniently via the Internet once they have been finalised. However, the problems of multiple versions existing, as well as limited control over the reports, are potential issues with this type of distribution method. It would be preferable for the project to have a centralised repository for the pottery reports (as well as any other reports or related materials) that was available over the Internet to be viewed and/or downloaded as needed. As the reports are updated and new findings are made, one central collection can house the material and be updated incrementally. It also becomes possible to manage the different versions by preserving and updating all earlier copies through this central location. In this way the entire process is preserved and available for investigation.

After receipt of the pottery reports, the findings are integrated into the database and ultimately into the GIS. Without being spatially referenced the pottery data is less useful to the overall aims and objectives of the project. Including the diagnostic information about the pottery found in the squares paints a much clearer picture of potential land-use and habitation patterns on the plateau. While the pottery and roof tile counts from the various areas are helpful, a comprehensive spatial database of the pottery experts' findings is a far more effective tool in identifying temporal and usage information. The creation of the spatial database with detailed ceramic information relies on the active collaboration of various members around the world.

Due to the overarching spatial nature of the survey at Sikyon, complex maps are required to use and present the data. The key components of the Sikyon data set are the number of sherds found, what kind of diagnostic pieces and other finds were identified, and the presence of architectural features. In particular, though, is where these different types of data were located. A high amount of pottery and roof-tile sherds in a specific area will naturally suggest that there was ancient use of that particular area of the plateau. Knowing how many sherds were identified in what square provides a key component of the current research at Sikyon. In particular areas of the plateau there is an identifiable absence of pottery and roof tiles found on the topsoil. The immediate suspicion would be that there was no habitation in that particular area. However, other factors must be taken into account such as whether the squares are located near the edge of the plateau or what kind of modern vegetation and farming are current in the area. If a tract that produced very few sherds is adjacent to a tract that produced a very high amount, it could be assumed that the farming methods employed are responsible for the variation in sherd density. There is also the possibility of differing habitation patterns in either tract, and the coincidence of the modern tract boundaries following that pattern. The spatial referencing of the environmental data (land-use and soil conditions), geophysical findings, and ceramic analysis, along with the sherd counts, provide comprehensive information into the different areas of the plateau. By using all the information and methods at their disposal, the various members of the project can draw more complete conclusions about the ancient urban environment of Sikyon.

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s)

URL: http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue23/5/2.4.html

Last updated: Tue Mar 25 2008