Figure 1: Location of the Biferno valley survey and Forma Italiae survey.

Figure 1: Location of the Biferno valley survey and Forma Italiae survey.

The first case study concerns the Biferno valley in the Molise region of central Italy. The results of two surveys will be discussed: the Biferno valley survey (Barker 1995a; 1995b) and the Forma Italiae survey of the area around the Samnite/Roman town of Larinum (modern Larino) (De Felice 1994) (Figure 1). The former sampled c. 400km² across the entire river valley (c. 20%); the latter covered a c. 100km² block at 100%. The two surveys were independent; the fieldwork for the Forma Italiae was conducted intermittently between 1969 and 1989 (De Felice 1994, 11); the Biferno valley survey was completed between 1974 and 1978. The final publications appeared in consecutive years; neither project makes reference to the other. By contemporary standards, neither survey presents detailed metadata. Of particular interest is an area of spatial overlap between the two surveys which offers an opportunity to examine two independent archaeological surveys of the same landscape side-by-side.

Both surveys published detailed gazetteers in paper form; while it is straightforward to access data about individual sites, it is difficult to appreciate broader patterns and to evaluate the surveyors' interpretations. To this end, the data from both surveys were digitised. In addition, a range of environmental data was collected including a DEM, hydrology and soils.

The surveys present their data in distinct formats. The Biferno valley survey uses a systematic format with information divided into 'byte-sized' pieces making it relatively straightforward to normalise and model within a relational database (Table 1). The free-text format of the Forma Italiae gazetteer requires a more flexible approach that is sensitive enough to contain the maximum information without compromising the resulting database's analytical potential (Table 2).

Table 1: Example of a Biferno valley survey record (#A1) with expanded details of gazetteer codes

| Record A1 | Details |

|---|---|

| LOC: 20 B3 109045 | Located on map sheet 20; square B3; 109mm from left/east margin of map and 45mm from top/north |

| ENV: alt 475, top 1, asp 0, geo 1, lu 1 | 475m above sea level, on Basin Floor, with no Aspect (i.e. flat), on Alluvial soils; land under plough at time of survey |

| ARC: 4a | Small, light density scatter of artefacts |

| INT: sp (7/10, 13/14) | Sporadic (off-site?) scatter of generic Classical period and post-medieval/recent activity |

| Finds: ccw3, qf1, tl | 3 sherds of Classical coarseware; 1 quern fragment; unquantified amounts of tile |

Table 2: Example of a Forma Italiae (Larino) survey record (#42) with translation

| 42. Villa? In località Pezza Don Pietro, m. 120 a SO di una casa di campagna (q. 414), sia a destra che a sinistra della mulattiera diretta verso la Masseria Petrucci sono sparsi frammenti di tegole, di mattoni e ceramica comune di epoca romana. È probabile che l'area (m. 200 x 60), in considerazione delle particolare collocazione topografica e del tipo di materiale rivenuto, sia stata occupata da una villa. |

| 42. Villa? In the vicinity of Pezza Don Pietro, 120m south-west of the farmhouse (at spotheight 414m), on both the left and right of the track towards Masseria Petrucci, are scattered pieces of tile, brick and coarsewares of the Roman period. Considering the particular topographical location and the type of material recovered, it is probable that the area (200x60m) was occupied by a villa. |

The data were therefore entered into separate databases, but wherever possible using the same structures and terminologies (both surveys, for example, used the 'site' or 'findspot' as the basic unit of record). The process of data entry involved rigorous checks and the enforcement of referential integrity (e.g. material had to relate to a known site); this identified a number of errors which were not apparent in the paper gazetteers.

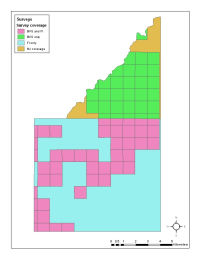

Figure 2: Larinum case study area. Spatial overlap of Biferno valley survey and Forma Italiae survey.

Once the attributes of these sites had been entered into databases, their grid references were derived in order that the two surveys could be intersected spatially and 'duplicate' records identified. Figure 2 illustrates the area of spatial overlap between the surveys. In order to identify which Forma Italiae findspots lay in close proximity to Biferno valley survey findspots, the latter were buffered (i.e. an area defined with a 150m radius around each findspot). These buffer areas were then overlaid onto the Forma Italiae findspots and those which fell within these 150m buffers were isolated for further consideration. This process identified 20 (out of 79, i.e. 23.5%) Biferno valley survey records with one or more Forma Italiae records within 150 metres; in total, 31 (out of 128, i.e. 19.5%) Forma Italiae records (excluding urban material) were found to lie within 150 metres of a Biferno valley survey findspot.

The attributes of each potential duplicate pair or group were then compared. In those cases where records clearly referred to the same archaeological feature, cross-references were created. The remaining examples were visualised in relation to slope (derived from the DEM) in order to assist interpretation. For example, thin, low-density ('sporadic') scatters found directly below large sites on steep slopes were considered likely to represent either an extension of the site or erosion of it. Cross-references were therefore created between these archaeological features. Where doubt remained over the relationship between records, they were kept separate. As a result of this process, it appears that the two surveys document the surface archaeology in different ways. The Forma Italiae survey uses approximately 50% more records to define the same features as the Biferno valley survey. In other words, on average, what the Biferno valley survey would record as 10 findspots, the Forma Italiae survey would record as 15. Recognition of this process of 'lumping' or 'splitting' is clearly significant if surveyors wish to undertake quantitative comparisons of site numbers and densities between surveys and regions.

Within the area walked by both surveys, how can we account for the fact that less than 25% of findspots were the same? If we assume that the archaeological record remained unchanged (a significant assumption, see below), then the differences are to be explained by the diverse aims and methods of the two surveys and the field conditions they experienced. The Forma Italiae represents a comprehensive catalogue of all archaeological evidence for Cultural Resource Management purposes compiled over many years; in contrast, the Biferno valley survey adopted a larger regional focus and aimed for an internally consistent sample through a briefer series of field seasons. A priori, it might be assumed that the Forma Italiae data would create a more comprehensive 'baseline' which the Biferno valley survey was only able to sample as part of its wider regional approach. However, this is not the case; there are 97 findspots not recorded by the Biferno valley survey and 59 findspots not recorded by the Forma Italiae. In other words, two different surveys, working independently, were able to identify a common group of findspots (recorded as 20 findspots by the Biferno valley survey, and as 31 findspots by the Forma Italiae), plus larger numbers unidentified by the other survey. One likely explanation is variable accessibility to fields and changing surface visibility within them. Despite the spatial overlap of the surveys, the surveyors may have encountered very different conditions within and between years (Ammerman 1985).

Another consideration is that the nature of the archaeological record itself may have changed. For example, the rapid erosion of surface material was noted at several sites identified and then revisited by the Biferno valley survey between 1974 and 1978 (Lloyd and Barker 1981, 290); it is possible that the nature of surface archaeology changed even more considerably over the extended duration of the Forma Italiae survey. This issue also raises a broader question of whether a definitive map should be the goal of (comparative) survey. Two surveys of the same region are likely to record different results. How then is it possible to make a definitive map, marking each site as a dot? A longer-term goal must be to use GIS to develop new ways of representing ancient landscapes at a variety of scales; not a single, definitive atlas, but a range of alternatives (Mattingly and Witcher 2004).

I have discussed the detail of data preparation at length in order to emphasise that this stage is not simply a preliminary step but integral to data analysis. Such detailed data handling facilitates important impressionistic understanding about the character of datasets. In other words, this is part of the process of source criticism. The generation of contextual metadata through an appreciation of data characteristics can subsequently inform more formal analysis. For example, through modelling and inputting data, it became clear that the Biferno valley survey contained its results within a limited number of interpretive categories; in contrast, the Forma Italiae was more flexible, though often reluctant to apply any interpretation at all. Similarly, it was noted that the Forma Italiae recorded more findspots overall, but this should be balanced against its tendency to use more records to document the same phenomena as the Biferno valley survey. Hence, data preparation can generate insight into the characteristics of datasets. Such work should be seen as an inherent part of a GIS approach to legacy survey data.

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s)

URL: http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue24/2/3.1.html

Last updated: Mon Jun 30 2008