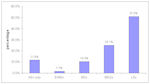

Figure 86: Chart showing proportion of PAS finds in south-east England categorised by broad period

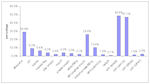

Figure 87: The artefact 'fingerprint' for south-east England

The EMC and PAS datasets for south-east England are closely comparable (Fig. 85), and are generally affected by the constraints in the area outlined in Section 2.4.2.5, although there is a line of coins recorded in the EMC that come from the Thames foreshore and from excavations within Greater London.

The pattern of early medieval finds is also comparable to the overall finds distribution (Fig. 26), with clustering in many of the same areas, including eastern Kent, most of the Sussex coastal zone, Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. Two differences are, however, apparent. Firstly, Romney Marsh and the stretch of the Sussex coastline immediately west of it are poorly represented by early medieval finds. Secondly, the Weald is virtually devoid of early medieval coins and other finds. Although there is a lower density of finds from this area during other periods, the complete absence of Anglo-Saxon finds must reflect the fact that this was a heavily forested area, with little human habitation, beyond forays for hunting. The extension of this empty zone to the Sussex coast is less expected, and may reflect environmental factors. However, the lack of coastal trading ports in this areas has already been noted, and the spread of finds and market activity into a rural hinterland may have been similarly controlled.

The absence of Anglo-Saxon finds from the area of the New Forest is not so obvious because the presence of the National Park here means that this is identified as an area of constraint. Nonetheless, it is probably a real gap relating to the presence of dense woodland here throughout the Anglo-Saxon period.

Figure 86: Chart showing proportion of PAS finds in south-east England categorised by broad period

Figure 87: The artefact 'fingerprint' for south-east England

When the PAS data is broken down by broad period sub-divisions (Fig. 86) we see quite a striking variation from the national pattern, with far fewer Middle Saxon finds and a greater number of Late Saxon finds, reflecting the growth of activity in this region under the protection of Wessex.

The artefact fingerprint (Fig. 87) also exhibits some differences from other regions. There is an even number of sceattas and pennies and very few stycas, as would be expected this far from Northumbria. There is a reasonable proportion of strap-ends but surprisingly few pins, which must reflect a regional difference in dress fashions and the display of cultural identity. By contrast, there is a large number of horse-related artefacts, especially stirrup-strap mounts. This may reflect the relative wealth of the region and the wider ownership of horses.

The coinage fingerprint (Fig. 88) shows a dramatic rise until 740, reflecting the preponderance of the silver sceatta coinage. This is followed by an equally dramatic decrease in coinage in the second half of the 8th century, and there is no second peak in the mid-9th century, as is seen in areas where the copper alloy styca coinage circulated. A gradual increase in coinage marks the first half of the 11th century.

In conclusion, south-east England in the case of the Weald of Kent and Sussex and a band of land extending to the coast and Romney Marsh provides the clearest example of the absence of early medieval finds indicating a real absence of settlement during the period. It also displays interesting variations in the proportions of a number of artefact categories that must reflect cultural differences within England.

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s)

URL: http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue25/2/3.3.5.2.html

Last updated: Tues Apr 21 2009