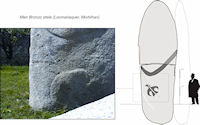

Figure 1: Men Bronzo stele (Morbihan, Brittany)

During the Neolithic, a great symbolic value was attached to quartz stones, particularly in funerary contexts (Cassen 2000a; Eogan 1974, 15, 40; Bergh 2002, 70). Quartz was used to enhance certain parts of the monuments but it was also integrated into carved compositions. Two examples from Ireland and Brittany show that linear quartz veins were regarded as a symbolic graphic form. The first example is a stele called Men Bronzo (Morbihan, Brittany), which dates to the Neolithic and has been recently been restored to an upright position (Cassen 2005). The stone is of orthogneiss and presents two veins of quartz (Fig. 1). A bird has been carved on one of them in order to make the quartz vein correspond to the flight path of the bird. Carvings and natural stone colours are combined here to make a symbolic representation.

The second example is from Athgreany stone circle, in Co. Wicklow, Ireland, where a quartz vein is also associated with a carving (Fig. 2). In this monument, a large boulder located 40m away from the stone circle has a vertical white quartz vein visible all around the stone. The stone is also carved with two deep lines that meet at right-angles on the top. One of these artificial lines has been carved all over the quartz vein. This natural white line was thus incorporated into a graphic representation and this shows that the feature was of interest for the monument builders, who probably gave it a symbolic function.

The geological nature of the stone was also taken into consideration in tomb building, particularly to complete the symmetry of the plan (see, for example, Fourknocks passage tomb) or to distinguish certain parts of the monument (O'Sullivan 2006). If there is a relationship between stone distribution and architecture, is there a connection between the spatial organisation of the structural stones and the spatial organisation of the carved motifs? At Knowth 13, the carvings on the kerb are clearly divided into two groups: serpentiforms on the left part and spirals on the right part (Fig. 3). Both motifs meet on the entrance stone: a serpentiform on the left and a spiral on the right. There is then an opposition of two groups of different signs from each side of the entrance to the tomb. Interestingly, a similar opposition can be seen in the kerbstone distribution. Two groups can be distinguished from each side of the entrance: on the left part there is a majority of dolerite, grit and sandstone while on the right there is a majority of limestone, agglomerate and slate. Parietal art and stone selection show here a similar spatial order. It seems that both media were used to express the same idea, the same principle of opposition.

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s) URL: http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue26/27/1.html

Last updated: Wed Jul 29 2009