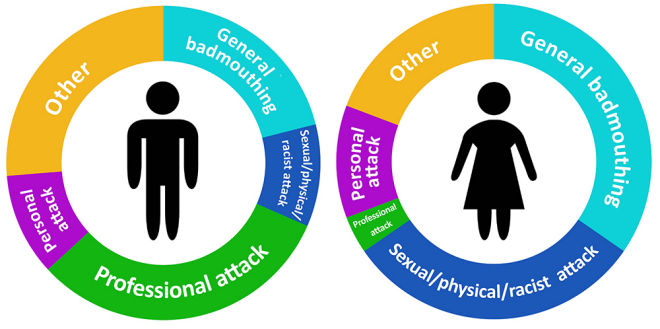

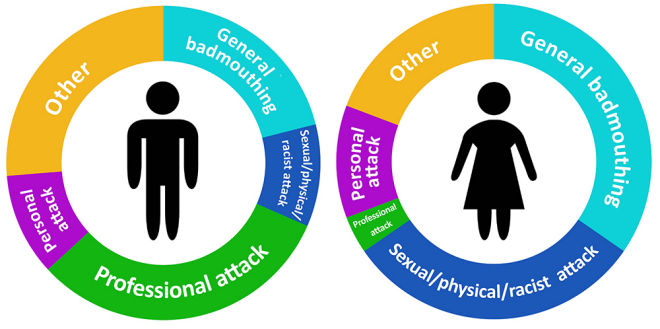

While quantitative reporting begins to chronicle basic patterns of behaviour within professional communities, rich qualitative data returned by a significant proportion of our survey respondents (130 of 397) provide an unsettling glimpse at the character and impact of web-based workplace communications. Of the subset of archaeology/heritage specialists who reported inappropriate or uncomfortable digital professional experiences, 82.1% provided long-hand detail. This detail was then coded into 24 categories according to the forms of abuse described, the types of reaction to such abuse which were reported, and related collateral impacts upon both the target and the perpetrator of the abuse. Respondents from the archaeological/heritage community discussed being victimised online in many manifestations, with the most common being general badmouthing and inappropriate comment (13 instances), followed by sexual, physical or racist threats and innuendo (10 instances), professional attacks directed at the respondent or on an institution/employer (7 instances), and personal attacks directed at the respondent (5 instances) (Figure 5). Men were most likely to report professional attacks directed at them or their associated institution (6 instances), whereas women were most likely to report sexual, physical or racist threats (8 instances) or general badmouthing and inappropriate comment (9 instances).

Long descriptive responses outlining the nature of these abuses make obvious their personal toll on the victim - psychologically, emotionally, and professionally. The vague character of the most commonly-reported category, 'bad-mouthing and inappropriateness,' conceals what is actually a plethora of different conflicts whose severity risks being minimised if we do not delve into the details. It is only through adopting a biographical approach, then, that the profundity of each incident emerges from the raw statistics. Respondents have been given pseudonyms, and are simultaneously identified by the automatically generated number assigned to their survey submission. For example, a male archaeologist, Mark (41), describes his experiences:

'The worst is the other professionals, and of those the worst was to receive copies of defamatory emails sent to developers by a fellow archaeologist that I have been acquainted with for over 30 years. They asserted that I was incompetent, inexperienced, untrained, unprofessional and so on'

A female archaeologist, Jane (40), explains how more open, exposed forms of social media have repeatedly been enrolled in undermining her:

'An ex student… posted trite/annoying comments on my Facebook wall, for example in one, making a joke about my having taken drugs. I asked him to stop, told him that I used my wall for social and professional purposes but he continued… Periodically I feel concerned about my Twitter account and I lock it down, but then I think “this is my life/my career”. If he [another persecutor, distinct from the ex-student] does ever cause trouble I'll have to deal with it.'

A female curator, Astrid (141), exposes the complex interplay between the personal and the professional that manifested through her experiences of harassment:

'The individual had been cautioned for breaches of legislation in my work role. Later he chose to try to contact me via LinkedIn (refused) and then trolls on Facebook posts on a forum of which we are mutual members. His identification of me was via the company policy that work email addresses be formed via name.surname@domain.com hence I was identifiable in my private life.'

And male archaeologist Joseph (390) explains his repeated online abuse:

'I received aggressive comments on my research blogging and engagement work on other websites. Propaganda about me and my work was published online (then syndicated to newspapers). A threat of surveillance was made on another website. I and my supervisors received e-mails as part of a (fortunately non-starter) campaign to have me censured for my research. I received a threat that I would be detained by the police the next time I entered the country in an e-mail.'

Many of these cases serve to illustrate wider patterns within our dataset, primarily the multiple incidents of harassment that many respondents described, accompanied by the spread and feedback of such incidents between online and offline worlds. Even where professional boundaries were more obviously asserted, for instance in working arenas such as academic conferences, they were repeatedly reported by respondents as easily manipulated and torn down via digital social media like Twitter. As male archaeology student Tim (130) recounts:

'At a conference I attended people were tweeting about the presentations and presenters in a way which (to my mind) would have seemed unprofessional and inappropriate were they using any other public/broadcast medium. Comments relating to the competence and vocabulary of speakers were tweeted and could be read by any of the conference attendees who were following the conference hashtag. I felt that at best this behaviour was naive and at worst it amounted to bullying. I don't know what the tweeters hoped to achieve through leaving these messages.'

Such abuse is not specific to online communication, but it is amplified by the digital platform. Indeed, the advantages of this platform are precisely the same as its disadvantages in the sense that it increases exposure and creates opportunities for known and unknown parties to come together in a form of collective, concerted action (whose intent may be positive or negative or mixed).

The gendered nature of many of these communications is attested to in various reports, with female respondents noting higher degrees of sexual harassment than their male colleagues. For example, female museum worker Mary (150) chronicles her experiences:

'I was asked overly personal questions about my sexuality and private life by a male colleague who I do not regard as more than an acquaintance. He asked a lot about my (then) girlfriend, whether I'd ever been with a man, what I liked in a woman (arse, tits or legs).'

Sofie, a female heritage management worker (351), describes 'messages filled with sexual innuendo from men'; while Richelle, a female archaeologist (291), speaks of her experience of: 'one incident, most distressing: [a male] wanting to get more personal, professing feelings for me.'

This kind of incident also appears in our dataset in relation to respondents' accounts of the experiences of their fellow professionals. Detailing her colleagues' exposure to abuse through the web, female archaeologist Dawn (20) notes that:

'All cases were women academics, contacted re their scicomm/more public activities, and comments they were uncomfortable with were universally of the “I'd do her” variety.'

Joseph encapsulates the experiences of his colleagues and friends in the profession as:

'Sexist comments, sexual harassment (perverted statements, fantasies).'

But others are clear about the more broad-based nature of online abuse and hint at the fact that certain forums perhaps facilitate or accommodate such behaviour. Female archaeologist Jacqui (381) describes it as:

'People being unnecessarily personal, attacking and negative. I don't post on the BAJR [British Archaeological Jobs & Resources] forums for exactly this reason.'

Another archaeologist, Greg (50), sums up what is evidently the spectrum of problematic behaviours manifesting in web-based media, saying it is:

'A range, from informal communications from students, to intrusive and inappropriately sexual communications from peers. The inherent ambiguity in some digital media added to the difficulty and confusion in many cases, as they blur the personal and professional, the public and private… in many cases this was just old fashioned crude abuse in new formats.'

The results of our qualitative enquiry hint at the extent and form of digital abuse in archaeology and heritage work. While many catalogued its different manifestations, and intimated at its impacts on personal safety and professional identity, others were reflective about its detrimental emotional ramifications. For female archaeologist Orla (4), the communications she was subjected to:

'made me feel inferior, that my view was not important, should not be shared, that I didn't have the right to share my own work online.'

Taken together, the accounts of archaeology and heritage practitioners correlate with our larger dataset, suggesting a series of trends in online work-related engagements. These include the fact that: