Jesse W. Stephen

Department of Anthropology, University of Hawai’i at Manoa, USA. jstephen@hawaii.edu

Cite this as: Stephen, J.W. (2015) Peer Comment, Internet Archaeology, (39). http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.39.10.com1

The contrast between blogging and traditional publishing brings to mind a similar dynamic between digital photographs and their analog antecedents. Media — both words and images — are increasingly accessible, astoundingly proliferate, intrinsically mutable, and sometimes (refreshingly and/or alarmingly) ephemeral. Ifantidis' photo essay alludes to complexities of depiction, scale, marginality, and processes of production and consumption in archaeological photography, yet also presents a counter-intuitive case for physical permanence and clarity of scale with two instances of his past and future works. I offer further commentary on the topics at hand by contributing two images and one video, which further address agency, objects, and architecture in archaeology, respectively.

Steven P. Ashby

Department of Archaeology, University of York, UK. steve.ashby@york.ac.uk

Cite this as: Ashby, S.P. (2015) Peer Comment, Internet Archaeology, (39). http://dx.doi.org/10.11141/ia.39.10.com2

The author here is clearly responding to a number of themes, and I would like to reply to these themes in kind, using 'not for publication' images relating to my own work.

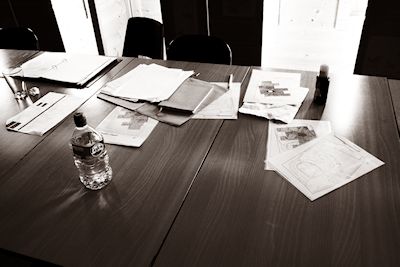

First, a key theme in the article is documentation of the 'moments between' in archaeological practice - the elements of fieldwork, labwork and so on that frequently go unrecorded, and are thus written out of the published record, replaced with more traditional images, whether of formal, objectified record (the photo-trowelled section), or more informal documentation of human involvement (the staged group photograph). No doubt such images have always been made, but are only being rendered visible through the web and social media. It will be interesting to see if this mini-revolution acts back onto the printed medium as in Archaeographies (Ifantidis 2013).

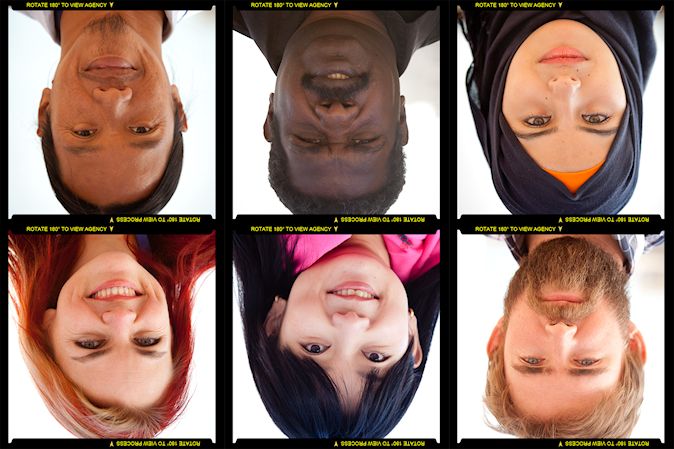

Second, Ifantidis draws our attention to the removal of the photographer's authority, and the tension between the public and the personal. This is tied to a related issue, that of the faced/faceless subject, and Ifantidis' work is notable for its deliberate inclusion of hands, yet the removal of faces. For all its cliché, I continue to find the disembodied hand powerful; an artefact in hand evokes that relationship between object and individual: the biography of material, manufacture, manipulation. But I don’t use the face.

Third, the issue of photograph as objective record. The question of scale and context are of course significant, and related: the presence of a scalebar in artefact photography does more than simply provide a sense of scale, it provides a scholarly and professional context for the image, as does the background in which the object is recorded. It is fun to play with these conventions, questioning (though not necessarily denying) their utility in various contexts.

It is nothing new to note the complicity of the photographer in maintaining the fallacy of objectivity in the creation of record (Shanks 1997). As all photographs are made and not taken (Adams 1980), and particularly now that images are so easily manipulated, we should increasingly call this practice into question. One suspects that any number of objective 'record' shots have had their brightness or contrast tweaked for the sake of clarifying a stratigraphic relationship, boosting impact, or simply tidying up. But at what point does post-processing become 'overdone'? Is it appropriate to take images in the other direction, to retreat from the pristine?

My thanks to Colleen Morgan for discussion and inspiration on these themes.