In the 25 years since the advent of PPG16 in England, the benefits and tribulations of grey literature as a data source for academics are well documented, namely the rapid rise of development-led works and the accompanying issues of accessing and collating the results (see Fulford and Holbrook 2011). As attitudes have begun to change, unpublished fieldwork outputs have been championed as valuable resources, providing insight into geographic areas outside the zones of traditional research interest (Vander Linden and Webley 2012). Thus, in England, a number of projects are taking advantage of the opportunity for national syntheses on a scale previously unimaginable, or achievable. However, there are potential weaknesses inherent in cultural collecting patterns based on modern development that are perhaps less well studied (see also Last 2012, 136). This is somewhat surprising, as national projects and sources such as AIP, OASIS and the Excavation Index have done much to compile and catalogue archaeological investigations and outputs (Evans 2013).

| Planning applications | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007-8 | 2010-11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East of England | 70978 | 76958 | 73973 | 44471 | 54898 | 66138 |

| East Midlands | 45214 | 35506 | 39340 | 45266 | 30489 | 42928 |

| London | 97870 | 104542 | 96977 | 89262 | 99394 | 114969 |

| North-East | 26523 | 28635 | 28118 | 26978 | 12000 | 20374 |

| North-West | 68610 | 83261 | 60398 | 49383 | 37211 | 48079 |

| South-East | 96246 | 109317 | 59340 | 60716 | 84839 | 82067 |

| South-West | 65832 | 41797 | 84309 | 83722 | 56394 | 88464 |

| West Midlands | 32392 | 39773 | 41352 | 21934 | 25915 | 27962 |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 59051 | 63098 | 62421 | 59249 | 53238 | 46973 |

| England Total | 562716 | 582887 | 546228 | 480981 | 454378 | 537954 |

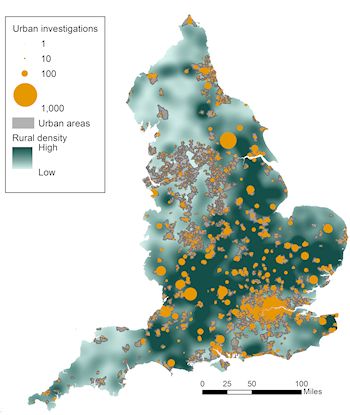

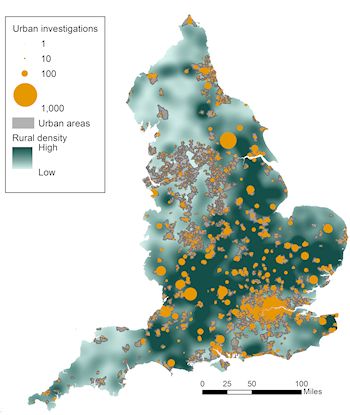

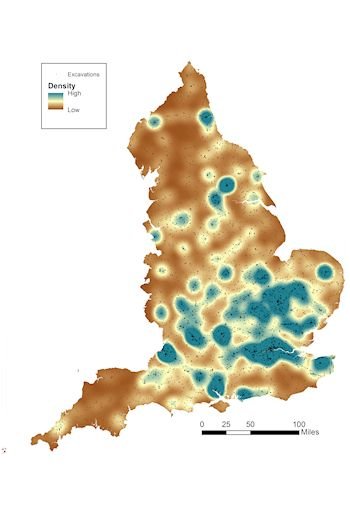

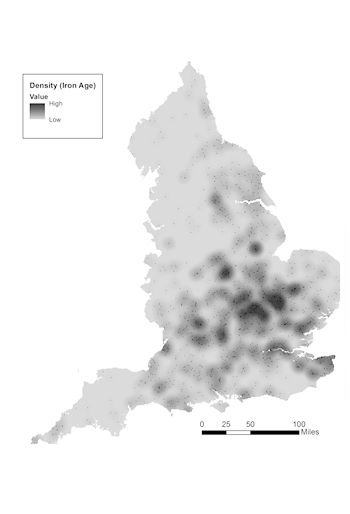

For example, a broad analysis of the available statistics shows that intrusive planning-led events undertaken since the advent of PPG16 have a marked unevenness in distribution (Figure 4). If these numbers are restricted to just excavations – as opposed to evaluations or watching briefs – the distribution is even more skewed towards a core zone in the south of the country (Figure 5). This pattern results from a combination of cultural and environmental factors underpinning the nature of modern development, and evident in the regional differences in modern planning applications and their potential impact on the historic environment (Table 1). This trend has been highlighted to some extent since the first analyses of development-led statistics (English Heritage 1995; Darvill and Russell 2002), but while noted in certain studies (Holbrook and Morton 2008; Morrison et al. 2014) analysis of the significance of these cultural collecting patterns has generally been lacking. This is arguably an important oversight, as the disparity in twenty years' worth of investigations has arguably created zones of core and periphery within the modern archaeological landscape. For example, if one wanted to examine 'Iron Age' sites encountered by commercial archaeology the resulting dataset shows a distinct geographical clustering (Figure 6). Thus, on a national scale the levels of data being produced, including unpublished reports, are a palimpsest of the modern planning landscape rather than an accurate depiction of the archaeological resource itself. Although patterns of bias are nothing new in archaeology, in the current climate of large-scale synthesis it is imperative that they are highlighted and factored into models of past settlement. Indeed, the most interesting questions may be what the data tell us about the limitations and our own roles in creating datasets of cultural disparity (see also Cooper and Green 2015).

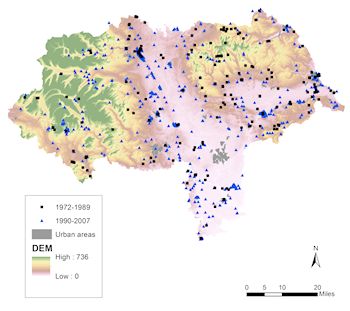

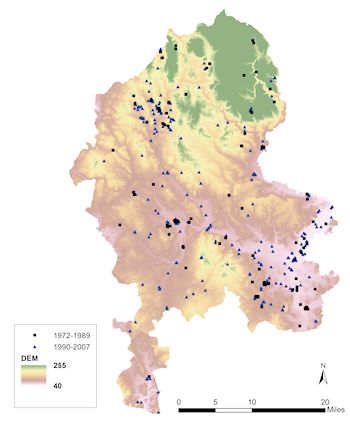

It may be argued that despite these national statistical discrepancies the advent of developer-engendered works still represents a distinct cultural break at a more local level. For example, looking at just two English counties – Staffordshire and North Yorkshire, respectively representing quiet and busy archaeological areas – it is evident that the advent of PPG16 represents a clear statistical leap from previous decades (Figures 7 and 8). However, it may also be observed that although the trend is for more investigations, these are increasingly geographically clustered around areas with higher levels of development, communication routes or areas of aggregate extraction; a consequence of the inexorable nature of threat and curatorial knowledge (Roskams and Whyman 2007; Powlesland 2011). Such criticisms of development or rescue-led archaeology are, of course, not new – since the first rescue excavations many authors have highlighted the uneven distribution of funds, and projects (Fowler 1977; Biddle 1994). However, the primary challenge over the last few decades has been one of collation and broad categorisation, and although some detailed work has been undertaken primarily through the Assessment of Assessments and AIP, there has been a distinct lack of follow-up on this work by the wider discipline as a whole (cf. Darvill et al. 1995; Darvill and Russell 2002). While we rightly celebrate an increased capacity to collate and synthesise, an increased predictability in where investigations have been, and are going to be, undertaken presents an interesting theoretical dilemma regarding the inherent entropy of the unpublished reports generated by so many projects; that is, the value of data in contrast to the whole (Justeson 1973, 132). As more of the same types of sites in the same areas are being excavated, does the information collected within fieldwork reports present new knowledge, or just more data?

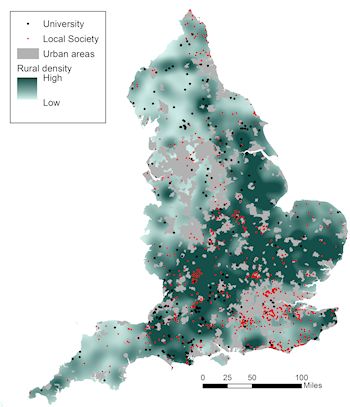

As an aside, it is interesting to note the extent to which this distribution compares to those intrusive events undertaken outside of the planning system, such as 'research' excavations by universities and local societies and other community groups or researchers. Although to a large extent these mirror the broad southern-centric patterns of investigation, there are notable divergences, particularly with the concentration of academic excavations in the central-south-west region (Dorset and Wiltshire) and the significant clusters of works undertaken by local groups in the areas to the south of London (Figure 9). For this admittedly very broad picture it seems that what may very loosely be termed cultures of 'research' and 'mitigation' (see Fitzpatrick 2012) have become physically disparate. It is notable that while the number of works being undertaken by these groups is significantly smaller, they are not insubstantial. In particular, community groups are responsible for a perhaps surprising volume of work (over 1000 intrusive investigations for the period 1990-2010 according to the Excavation Index). Of course the relative size of these investigations should be taken into account; multi-period large-scale works versus short bursts of work by relatively small numbers of people. Issues of scale and significance apart, there are clearly significant important levels of work produced outside of contract archaeology (see also Holbrook and Morton 2008). Conversely, it may be suggested that whereas rescue/development-led works were once highlighted as a counter-balance to the monument-based biases of previous research, it seems that the activities of modern community-based research groups may present a geographical alternative to commercial archaeology. However, as previous studies have shown, it is these groups rather than contracting units that are under-represented in the collections of HERs and national databases of AIP and OASIS (Brookes and Pearce 2003; Evans 2013). The real 'grey literature', elusive and ephemeral, may well be that written and produced outside the control of the two cultures of academia and development.