The pendant was found within context 317, a brown-green fine detrital mud containing a high proportion of organic material within the matrix. The contexts are currently being dated and modelled using Bayesian statistics by Alex Bayliss (Historic England) but at present it is possible to say that these sediments formed at around 9000 cal BC. The pendant was deposited into shallow water, at least half a metre deep and approximately 10m from the lake shore. Reeds, sedges and a suite of aquatic plants were all growing in the immediate area, forming a species-rich swamp environment.

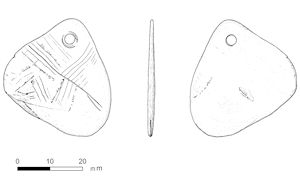

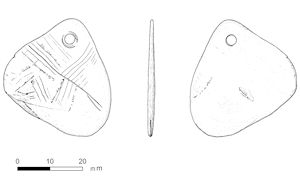

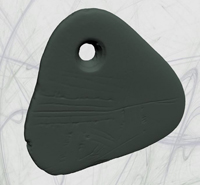

The pendant is sub-triangular in shape, measuring about 31mm by 35mm and 3mm thick (Figure 4). ED-XRF (energy-dispersive x-ray fluorescence) analysis was carried out to confirm whether it was made of shale (Rowley and Needham 2015). Element concentrations were measured using an Olympus Delta Portable ED-XRF Analyzer. The elemental composition data was compared with that published in Rowe et al. (2012) and can be demonstrated to be consistent with the composition of shale.

Unfortunately, the artefact sustained damage from trowelling towards the base of the engraved surface. These marks appear as light scratches and are easy to differentiate from the fine engraved lines. The stone is fragile with the potential to laminate, hence much care has been taken when handling it, and powder free nitrile gloves were worn to avoid contamination in advance of residue analysis.

There is a perforation in one of the vertices that has been made by drilling through from the engraved side of the pendant. The engravings appear on one side only and the lines are very faint: the smallest lines are hard to distinguish from one another with the naked eye. The artwork uses the incision method which is the most common and least specialised of Early Mesolithic artwork, the other types being pricking and drilling to create dots (Clark 1936). Most of the lines can be classified as linear and in Clark's terminology barbed lines of 'type C', i.e. lines that come off another line at right angles (Clark 1936, 169).

On the reverse side to the engraving there is a nick caused by a missing flake of shale in the central region, shown clearly from the scan of the artefact (Figure 5). This may have happened accidentally or intentionally, presumably by something hard striking this surface before it was deposited in the lake.

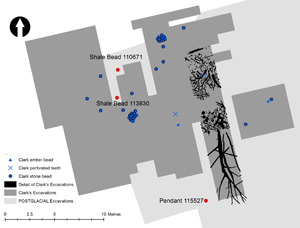

This artefact is being termed a 'pendant' because the perforation is not central, implying that it may have been suspended and worn as a necklace. The other perforated shale objects at the site were defined as 'beads' by Clark since the perforations are more or less central, the only exception being the 'celtiform bead' (Clark 1954, 165) which could in fact also be classified as a pendant (Figure 6). It is unclear how the shale beads from Star Carr were worn: whether they were items of jewellery or perhaps appliqués (Cristiani et al. 2014a; Langley and O'Connor 2015). Further use-wear analysis on these other beads is planned, and will aim to address this question. Of the three pieces of amber found, one was classified as a pendant; this piece has two holes at the top (Figure 7) (images of most of the finds from the original excavations by Clark can be found in the Archaeology Data Service Star Carr Archives Project: (Clark 1954; Milner et al. 2013a).

In the 2015 excavation, two further shale beads were discovered that are typical of the majority of beads found by Clark. What is noteworthy is that these beads were not found in the same context as most of the other archaeological material that Clark excavated. Instead they were recovered from the wood peat that dates to approximately 100 years later than the phase to which the engraved pendant and the headdresses belong. Although Clark (1954, 19) plotted the spatial distribution of many of the artefacts from his excavations in his monograph (see Figure 8), the depths were not recorded and the archive appears to have been destroyed (Milner et al. 2013a). From our current understanding of the stratigraphy and typology of the artefacts, it is likely that the small shale beads are later in date than the engraved shale pendant. It is always possible that the amber pendant and celtiform shale pendant were contemporary with the engraved pendant; however, as there is no contextual information for those finds, this hypothesis will remain unresolved.