Cite this as: Russell, O., Daffern, N., Hancox, E. and Nash, A. 2018 Putting the Palaeolithic into Worcestershire's HER: An evidence base for development management, Internet Archaeology 47. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.47.3

English Historic Environment Records (HERs) contain a wealth of data, but entry of this data into the record has been haphazard over the last c.50 years since their creation (originally as Sites and Monuments Records) and there are big gaps in knowledge. This can make evidencing the need for mitigation through planning more challenging. In areas, or for periods, where there are no known heritage assets, a strong case needs to be made to look for potential sites. In order to make that case, areas of potential need to be targeted and evidenced. A number of projects have been undertaken nationally to address this bias and start to synthesise the vast amount of data held within HERs to provide a more contextual approach. In Worcestershire a particular area of concern was the lack of knowledge regarding the early prehistory of the area. It was felt that there was a clear need to pull together the existing artefactual and environmental evidence and reassess it in order to provide a better understanding of existing knowledge and a framework for future mitigation advice.

Worcestershire, like the majority of the West Midlands, is not considered a focal point for the study of Palaeolithic archaeological remains, with much of the focus occurring in the east and south-east of the country through projects such as the Ancient Human Occupation of Britain project. Brown (2011, 28) notes that "Remarkably little geological dating has been undertaken in the Middle Severn Valley in comparison to its left-bank tributary the Worcestershire Avon and other systems such as the Thames and the Trent". However despite this somewhat bleak overview, discoveries of Palaeolithic artefactual and palaeoenvironmental remains within the county and the wider West Midlands over the last 30+ years have shown that the area has the potential to be productive and assist in national and international research aims for the period.

Worcestershire benefits not only from the existence of two extant river systems, whose terrace sequences are well-preserved and have demonstrated the presence of both artefactual and palaeoenvironmental remains (Jackson and Dalwood 2007), but also the remains of pre-Anglian river systems that have the potential for the preservation of palaeoenvironmental, and possibly artefactual, data from a key period in the Palaeolithic of Britain (Barclay et al. 1992, Coope et al. 2002, Shotton et al. 1993).

A Historic England (formerly English Heritage) funded project (Putting the Palaeolithic into Worcestershire's HER) was undertaken by Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service in 2013/14 and aimed to begin to address the limited understanding of Worcestershire's Palaeolithic, and to incorporate the results within the Historic Environment Record in a way in which it could be interpreted and used by non-specialists. The impetus for the Worcestershire project was the Shotton Project, which was an English Heritage-funded project in 2003 run by the University of Birmingham to promote the Palaeolithic in the Midlands to a wide range of archaeological and non-archaeological stakeholders. The project was named after Professor Fred Shotton, a geologist, natural historian and Fellow of the Royal Society. As an unfunded addition to the Shotton project, Worcestershire HER staff had worked with Quaternary scientists and archaeologists to classify the river terraces into dated groups, making the geology more accessible to non-specialists (Buteux et al. 2005, 42-50). In addition some new sites were added onto the HER (Lang et al. 2008). This was recognised as a simple but effective approach to make Palaeolithic data accessible to a non-specialist audience, but lack of funds meant that a comprehensive and systematic catalogue of all Palaeolithic material from the county could not be undertaken, nor any assessment of existing material by a Palaeolithic specialist. The 2013/14 Putting the Palaeolithic into Worcestershire's HER project aimed to address this.

One of the key aims of the project was to create an effective evidence base for targeting and justifying archaeological interventions through the planning system, where previously it has been difficult to present a cogent argument in the context of the National Planning Policy Framework (Russell and Daffern 2014).

The initial stage of the project was a literature review covering a wide variety of journals, publications and online resources, making use of keyword search functionality on websites to pick up potentially relevant sites. In addition to the 'standard' archaeological sources, Quaternary science and geological literature was reviewed as this is frequently overlooked by archaeologists and the datasets are rarely deposited with Historic Environment Records. Alongside this, local and national museums were asked to provide a list of Palaeolithic material in their collections. The results of the literature review and the catalogue of known material provided a basis for stages two and three of the project. It is likely that the catalogue of lithics is incomplete, as many museum collections have never been assessed by a specialist and misidentifications are highly probable. Together, however, the review and the catalogue provide a good indication of potential and give a clearer idea of work that could be undertaken in the future.

The second stage of the project was the re-assessment of artefacts within museum collections carried out by Dr Andrew Shaw (2013). In addition to smaller collections held in local museums, the key assemblage was the Whitehead collection held at the British Museum. Paul Whitehead is a natural historian who has worked in Worcestershire and neighbouring counties over the last c.40 years. He is responsible for finding around 90% of the Palaeolithic material in the county, the majority of which comes from observing the workings at just two quarries. A total of 304 lithic objects were examined, of which over 79% were of Palaeolithic date, increasing the number of firmly dated Palaeolithic artefacts within the Historic Environment Record from less than 10 to 261. In addition, Whitehead's catalogue of faunal remains was also incorporated into the HER. As a result, Worcestershire HER now has records of over 2000 Pleistocene faunal remains rather than a handful.

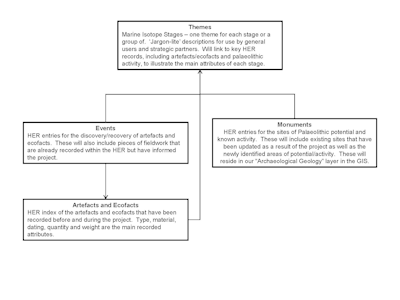

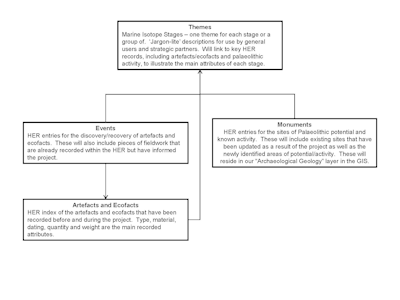

The third stage of the project was creating and mapping records within the HER (Figure 1). Firstly, the artefactual and faunal material were spatially located within the GIS and given linked records in the HER database. The second task was to enable this data to be used strategically by mapping areas of Palaeolithic potential. This was achieved by using polygons from the British Geological Survey (BGS) data which were overlaid with the enhanced HER entries (Figure 2a and 2b) and merged into one polygon per member/deposit. Using this method, the project created 21 areas of Palaeolithic potential, each of which has an entry within the HER's Geology layer. For each geological area of potential, evidence was added to the database record, including the deposit dating obtained during the Shotton project and a list of artefactual and ecofactual material discovered within the deposit previously.

Marine Isotope Stages were used for the dating of the project results. It was felt essential to incorporate Marine Isotope Stages as this chronological framework is widely used in Quaternary Science publications and the majority of the geological, climatic and environmental data, in which the archaeological record sits, is presented in this format. This is particularly apparent in the recent works of Penkman et al. (2011) and McMillan et al. (2011) whose aminostratigraphic and lithostratigraphic frameworks for the British Quaternary are presented in Marine Isotope Stages. The dates for the MIS boundaries in the Worcestershire HER are those that are shown in Lisiecki and Raymo (2005).

By using Marine Isotope Stages, a better context for activity can be achieved. For example, the middle Palaeolithic, a range of c.150,000 years, is grouped together and seemingly gives the impression of constancy when in reality the period is characterised by vast climatic and environmental variations including the Wolstonian stage glaciations and the Ipswichian interglacial. The climatic and environmental context would appear to be a better chronological framework than that of slight, heavily-debated morphological variations in artefacts which may reflect short trends.

Within the scope of the project, and because of the lack of more refined dating techniques, most records are broadly dated to MIS ranges which reflect the more traditional (Upper, Middle and Lower) tripartite dating. This means that broadly dated material is still represented without making assumptions as to which stage it belongs, yet ensures that the HER is 'future proofed' allowing for refinements in dating and easy incorporation of new datasets from Quaternary Science sources. Each MIS has its own 'Theme' record within the HER (Figure 1), which details the national and regional conditions at that time and what faunal remains are to be expected from each stage. These act as extended Scope Notes for each MIS and have been created as plain English descriptions of each period.

The polygonised areas of potential, with supporting evidence, form the basis of the Palaeolithic Toolkit. This is to advise local planning authorities and archaeological contractors of the potential Pleistocene deposits in Worcestershire, in order for the impact of development on them to be considered and form part of the mitigation strategy where appropriate. The toolkit and report are available online (Russell and Daffern 2014).

Palaeolithic archaeology and Pleistocene remains are particularly at risk due to their very nature. They are most frequently encountered within sand and gravel quarries yet often overlooked on these sites when there is no provision made for 'deep archaeology'. The remains are not found because they are not looked for and they are not looked for because they are not found (Buteux et al. 2005). This is a particular issue in areas like the West Midlands where the evidence is more sparse than, for example, the south-east of England, and therefore it is harder to justify the expense of looking for it.

The mapping of areas of Palaeolithic/Pleistocene potential via this project has enhanced the evidence base in a way that allows it to inform the placing and working of aggregate extraction sites and increase the awareness of Palaeolithic archaeology without the need to carry out extensive, and costly, fieldwork investigations on all potential and existing sand and gravel quarry sites. The areas of Palaeolithic/Pleistocene potential can also be used to inform local planning policies. In the time since completion of this project, the results have been used to inform Worcestershire's Emerging Minerals Local Plan. In the first phase of identifying potential future aggregate sites, all the options were assessed against the GIS data of Palaeolithic potential. This allowed identification of those deposits which could be impacted at the earliest opportunity, thereby giving minerals planners the ability to make more informed decisions.

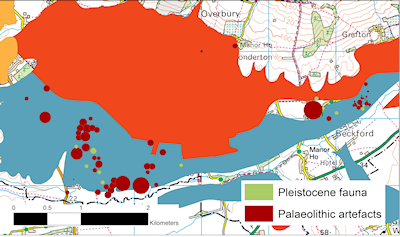

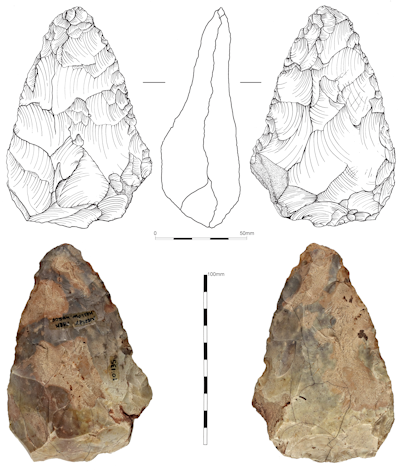

The reassessment of the artefactual data (Shaw 2013) demonstrated the value of reassessing existing collections, with new information coming to light and a number of interesting conclusions being drawn. Significantly, this reassessment has potentially identified the first Early Middle Palaeolithic artefact from the West Midlands (Moseley Park). Shaw notes that this has the potential to be important, as it is the first in the West Midlands to have clearly been assigned to this period, whilst its good condition suggests it may have come from a relatively undisturbed context (Figure 3).

It is important to note that while aggregate extraction sites have traditionally been the focus for Pleistocene/Palaeolithic deposits, the results of the project are also used when assessing more standard developments. The project has resulted in an increase of knowledge relating to the depths of deposits, which is invaluable in determining if fieldwork is required as a result of proposed development. In many instances, deposits of Pleistocene date can be 8-10 metres or more below ground and as such, most developments are unlikely to impact. However, the project has shown that some deposits such as those at Eckington are closer to the surface. It is therefore necessary to apply a pragmatic approach on a site-by-site basis.

The discovery of a Pleistocene vertebrate assemblage further down the River Severn in Gloucester, demonstrates clearly that there are occasions when small developments (in this case 37m x 32m) with relatively shallow foundations can impact on significant Pleistocene deposits. The remains from this particular site included the presence of hippopotamus, indicating a need to rethink the dating of the terrace deposit (Schreve 2009). It had been assigned a MIS7/6 (243,000 to 125,000 years ago), but hippopotamus suggests MIS5e (125,000-110,000 years ago) material must be present.

Both the faunal and the artefactual material recovered in Worcestershire suggest similar issues with the terrace dating further up the Severn. Assessment and integration of Whitehead's notebooks are required to fully understand the implications of the initial findings, but there are now deposits identified that have potential to allow us to better understand the Severn terraces and their dating, as well as providing further artefactual evidence. These deposits can be targeted through development management and assessed. Mapping the stratigraphy of exposures in quarries and identifying areas that would benefit from techniques such as Optical Luminescence Dating (OSL) will start to address the questions and fully understand the potential.

The project has demonstrated how revisiting and analysing existing data and collections can be used successfully to inform strategic decision making. It has realised the potential of the 'hidden' resources that sit within our archives, grey literature and museum collections, in particular, the wealth of information from private collections which, without being formally recorded and included within HERs, remain invisible to the planning process.

Its ongoing use in archaeological planning advice has demonstrated the need for a more tailored and knowledgeable approach to the employment of the correct fieldwork techniques. Archaeological curators are not necessarily specialists in Quaternary science or geoarchaeology, therefore, it is necessary to empower them by ensuring access to specialist knowledge and/or CPD in these areas in a format that is readily accessible and in non-specialist language. This will enable archaeological curators to provide a more tailored and knowledgeable approach, ensuring cost-effectiveness for developers and providing more detailed information that can be used to further underpin the process.

Putting the Palaeolithic in Worcestershire's HER is one of several strategic regional projects which have collected and analysed datasets from HERs. Two examples of this are the Roman Rural Settlement Project and the Analysing change in the English Landscape Project (EngLaID), both of which requested data from all HERs nationally. Projects such as these look at the data as a whole, and regions without comprehensive datasets can easily be underrepresented. Through HER enhancement provided by this and other such projects, local and regional archaeological knowledge can contribute to national research frameworks and questions.

Following on from the project funded by Historic England, Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service, Museums Worcestershire and The Hive have subsequently obtained funding, chiefly from The National Lottery and Arts Council England, to run exhibitions and events celebrating the County's collections and conducting further research into this period http://www.iceageworcestershire.com

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.