Cite this as: Law, M. 2019 Beyond Extractive Practice: Bioarchaeology, Geoarchaeology and Human Palaeoecology for the People, Internet Archaeology 53. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.53.6

In his introduction to the volume Environmental Archaeology: Meaning and Purpose (hereafter Meaning and Purpose), Umberto Albarella (2001, 4) described 'a profound fracture existing between archaeologists dealing with the artefactual evidence and those engaged in the study of biological and geological remains', a fracture that effectively serves to marginalise the work done within what Ken Thomas (2001) later in the volume terms 'bioarchaeology, geoarcheology and human palaeoecology'. Albarella (2001, 4) sought contributions for Meaning and Purpose from 'a diverse group of contributors', with the hope that such diversity would help extend the debate about the role of environmental archaeology and allied sub-disciplines to 'all sectors of the archaeological community'.

A notable sector of the archaeological community was overlooked in Meaning and Purpose, however. None of the contributions spoke of avocational archaeologists who work, often in a voluntary capacity, outside of what we might think of as the established archaeological community: the academy, the commercial sector, statutory bodies and museums. Indeed, with the exception of the last sentence of Graeme Barker's discussion paper (Barker 2001, 313), the idea that environmental archaeology might have any value to the community in general is not considered.

This oversight is unfortunate, but understandable in the context of a debate among professional practitioners. To perpetuate the oversight, however, would be to do a disservice to significant contributors to archaeology in the UK, and to misrepresent the nature of archaeological practice at this point in 21st-century Britain. Research conducted by the Council for British Archaeology in 2010 found evidence that there are at least 2030 community groups in the country that 'interact with archaeological heritage in a wide variety of ways', and that this represents at least 215,000 individuals (Thomas 2010, 5), a figure that is likely to have grown in the intervening years (Neal 2015). Nationwide, projects by community groups are estimated to have contributed to over 20,000 research outputs (defined broadly to include websites and interpretation panels among others) between 2010 and 2015 (Historic England 2016).

The 2010 research did not examine the relationship between community archaeology groups and bioarchaeology, geoarchaeology or human paleoecology, beyond noting that two of the groups who responded to a survey stated that they would welcome training in 'specialist topics such as specific pottery analysis or environmental archaeology' (Thomas 2010, 55). Indeed, the relationship between professional specialists within the archaeological community and non-professional participants in community archaeology does not appear to have been explored in depth in literature, although a 2016 study into the value of the historic environment research carried out by community groups (Historic England 2016, 37) found that 20.3% of respondents (total respondents n=542) carried out 'other' original research, a category that included research-led conservation, ecological and palaeoenvironmental research. The CBA research does note a possible 'lack of awareness on the part of the professional archaeologist of the existing abilities of volunteers (many of whom bring with them skills from other disciplines)' (Thomas 2010, 5), a valuable point that serves to caution us against assuming that the expertise is all held on 'our' side of the equation. More recently, Orange and Perring (2017) have presented an overview of the range of ways in which commercial archaeological units in the UK interact with the public, ranging from informal conversations with members of the public passing a site to fully realised community engagement projects where non-professionals work alongside professional archaeologists.

This article seeks to make a modest contribution to recognising the importance of active relationships between (in Ken Thomas's terms) bioarchaeologists, geoarchaeologists and human palaeoecologists (the BGHP community?) and community archaeology groups. This importance not only relates to the quality and sustainability of the work carried out by community groups, but also to the quality and sustainability of work carried out by us, the 'specialists'. The results of two surveys, the first of community archaeology groups, and the second of self-identified environmental archaeologists, are presented, along with an agenda for future development of the relationship between specialists and community groups.

The terminology of archaeological practice is always controversial (see Driver 2001 and the response by Thomas 2001). This is no less the case with 'community archaeology' (see Thomas (2017) for a recent discussion of the definition of 'community archaeology'). In this article I am primarily interested in palaeoenvironmental work carried out with the direct input of avocational archaeologists, a situation encompassed by Type 1 and Type 2 of Gabe Moshenska's typology of public archaeology (Bonacchi and Moshenska 2015). Similarly, I have been somewhat capricious with the kind of 'bioarchaeology' that I am discussing, focusing on bioarchaeology as it relates to the environment and/or economy of a site, rather than work around burials and human osteoarchaeology. The survey focused on community groups and workers in the UK, and discussion is limited to a UK context.

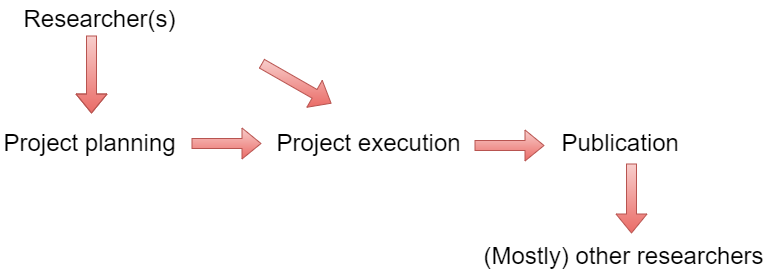

In addition to the relationship between BGHP specialists and community groups, the issue of how specialists interact with the communities inhabiting their study locations is of interest. To borrow the language of sustainability (e.g. Klein 2015), much specialist work could be described as linear and extractive, following the model in Figure 1, in which results are generally not directly fed back to local communities. In this model, samples are taken from the locale of interest, analysed by researchers who may be working at institutions some distance from the local community, and the results communicated via publication or (more often) in grey literature, but generally with other (professional) researchers as the intended audience rather than people living in or otherwise attached to the study locale.

This approach overlooks the duty, as outlined by Sir Mortimer Wheeler 70 years ago, of 'the archaeologist, as of the scientist, to reach and impress the public, and to mould his words in the common clay of its forthright understanding' (Wheeler 1956, 234). Wheeler saw this not just as a means to court funding, but also a 'moral necessity' (Wheeler 1956, 102). More concretely, the positive impacts (in terms of personal and community well-being) of engagement with the historic environment have been explored and highlighted by English Heritage (2000) and Neal (2015).

There is an increasing number of exceptions to this model, however, as public engagement and impact become normalised in archaeological work and in funders' expectations of academic research. Recent projects in the UK have highlighted the significance of BGHP work in archaeological context, especially via project websites. Commendable examples of this include Cambridge Archaeology Unit's excavations at Must Farm, or L-P: Archaeology's work at Prescot Street, London. However, projects like these remain the exception for BGHP work. Other projects, such as Big Heritage's Eco-Vikings or Cardiff University's Future Animals have engaged school groups with BGHP research and provoked discourse about modern lives in relation to the past. Arising from the latter project, the Association for Environmental Archaeology have produced a set of resources for public engagement events (Mulville and Law 2013).

Deeper engagement involves volunteers in the production of palaeoenvironmental knowledge, however, and in this context two projects from the University of Exeter, based in the Devon landscape, are of note. The first, established in conjunction with Devon County Council's historic environment service, was the Community Landscapes Project. This ran between 2001 and 2004, and investigated various sites in the county through documentary research, fieldwork and pollen analysis. Community involvement was at the heart of its design, with volunteers involved in documentary and GIS research, and coring and sub-sampling for pollen (a combination of health and safety concerns over harmful chemicals and the time required to master identification prevented volunteers from carrying out pollen analysis, although volunteers were able to look at pollen slides under the microscope) (Brown et al. 2004).

A subsequent project, 'Landscape archaeology and the community in Devon: an oral history approach', aimed to 'recentre members of the public, not simply as armchair consumers of archaeological knowledge, nor even as participants in the practice of scientific archaeological data collection, but as knowing agents in the construction, mediation and development of archaeological knowledge' (Riley et al. 2005, 15). The project used interviews with people who were working the land during the Second World War in order to augment archaeological knowledge of particular landscapes in Devon.

In an attempt to gauge the degree to which community archaeology groups are engaging with specialists in biological and geological remains, an online survey was conducted over the summer of 2015. The survey link was posted on the British Archaeological Jobs Resource Facebook group, and the Council for British Archaeology and Archaeology Scotland offered to share the link with members. One hundred community archaeology groups, listed on the BAJR directory, were emailed directly.

Results were underwhelming. A total of ten responses were received, one of which came from a commercial archaeology unit in northern Spain(!). Clearly, the results of this survey are not a representative sample of the >2030 community groups active in the country. Nonetheless, they are presented and discussed in brief below for their qualitative value.

Of the ten respondents, five said they had an active programme of excavation. Seven (UK) groups responded that they self-funded their own excavations, or made funding available for fieldwork. Three of the groups said that they do take sediment samples for analysis, one group saying that the director of the excavation decides what should be sampled, while another stated that two volunteers run a business processing archaeological samples, so they make the decisions. One respondent, whose group do not take samples, held the belief that there is no value sampling more recent contexts:

'At the moment we are not working on sites that date to before 1939, so not yet'

Four groups stated that they had worked with an expert in biological remains or soils and sediments, and three groups replied that a student had looked at samples from their fieldwork. Two groups that had not worked with specialists or students replied that it was not appropriate to do so due to the recent date of the material they were excavating. Another stated that they did not have sufficient knowledge or funding to pay for the analysis. Five groups said that in principle they would be interested in co-creating a research plan for a site of interest with a specialist.

Seven of the groups said that they had an active programme of talks and workshops, although only one said that an expert in biological or geological remains had spoken. One group stated that they had not had such a speaker because they don't know one. Another group replied that:

'As the vast majority of our members are more interested in local history we do not think there would be sufficient interest'

Although a small sample, the responses do give some encouraging signs of enthusiasm. Two recurrent problems appear, however. The first is a lack of access to specialists, or funding to commission them. A second is evidenced in comments that apparently exclude bioarchaeology, geoarchaeology and human palaeoecology from local history, or suggest that they are not appropriate lines of enquiry for more recent contexts. These are both areas in which we the specialists can work harder, by actively engaging with community groups.

To evaluate how actively specialists do engage with community groups, a second survey was carried out. This survey, of UK-based specialists in biological and geological remains, ran in the first two weeks of December 2015. It was advertised solely on the Association for Environmental Archaeology's JISCmail list, and attracted 48 responses. Fifteen respondents described themselves as zooarchaeologists, 14 as archaeobotanists, 9 as geoarchaeologists, and 3 as palynologists. Individual respondents described themselves as specialists in phytoliths, molluscs and sclerochronology. A total of 33 of the respondents were not members of a community archaeology group, although 32 had given a talk about their specialism to a community group. Almost half (23) had visited a volunteer-led excavation to give advice about their specialism, although only 7 of those were paid to do so.

Thirty-two respondents had undertaken specialist work on behalf of a community archaeology group; 11 of them were paid for this work. Twenty-two respondents had delivered training in their specialism to a community archaeology group; 8 of them were paid for this. Only 8 respondents had been involved, as specialists, in planning a volunteer-led excavation. All 48 respondents would, in principle, like to work with community archaeology groups.

Respondents identified time, money and workload as common barriers preventing their participation in community archaeology, while one noted that there is:

'Lack of interest in geoarchaeology, [and a] fear of complexity'

When asked about advantages of working with community groups, respondents listed good PR, the opportunity to acquire additional data, and to learn more about local archaeology. One respondent praised the enthusiasm of volunteers:

'Satisfaction of working with people actually interested in the subject as opposed to most undergraduates.'

Another noted that they could act as a positive role model:

'As a wheelchair user I hope to encourage people with disabilities to take part in archaeology, it doesn't have to be a barrier.'

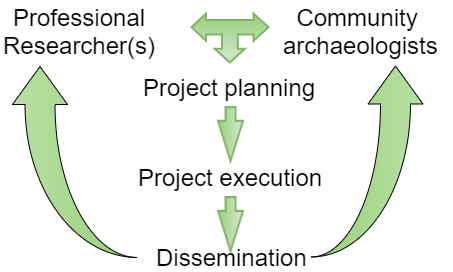

The surveys reveal a broadly positive attitude towards community participation from specialists, and for specialist involvement from community groups (and one Spanish commercial unit!). Harvesting this positivity presents an opportunity to move beyond the extractive, linear way of working identified above to a more circular, reciprocal (to once again borrow the language of sustainability) practice that involves members of local communities (Figure 2).

Some simple actions contribute to an agenda for circularity and reciprocity:

Such a circular, reciprocal approach may also be beneficial for the sustainability of specialist practice. Close liaison with community groups creates demand for specialist services, which may lead to commissions for contract work. Communities also contain potential future specialists. Both the 2010-11 Survey of Archaeological Specialists (Aitchison 2011) and the 2016 Archaeological Market Survey (Aitchison 2016) reveal that a shortage of specialists is a matter of concern among archaeologists, although respondents to the 2016-17 Survey of Archaeological Specialists were less concerned about loss of specialists. Nonetheless, 13.5% of all specialists were planning to stop work within five years (Aitchison 2017). As one of the respondents to the community archaeology survey noted:

'Individuals come from a wide background. Most of the volunteers I work with are retired professionals, from GPs to Professors.'

It may well be that there are already specialist skills within community groups. Even if there aren't, there may be potential future specialists. As an example, the South Somerset Archaeological Research Group is a community group that emerged from the Arts and Humanities Research Board (as was) and funded South Cadbury Environs Group, led by Bristol and Oxford Universities in the early 2000s. Local volunteers took part in the fieldwork, which included geophysical survey (magnetometry and resistivity). Building on training received during the project, members of the community group subsequently established GeoFlo, an archaeological services company specialising in geophysics and sample flotation.

Public engagement with bioarchaeology, geoarchaeology and human palaeoecology also holds relevance to modern society. Many of our areas of research provide time depth and context to 'wicked problems' (sensu Rittel and Webber 1973), such as climate change, biological conservation, sustainable resource use and human migration (see, for example, Guttmann-Bond 2010). As Martin Bell (2004, 509) has noted:

'Green concerns are about current and future trends. However understanding them requires knowledge of what has happened in the past.'

Participation in data collection and interpretation may influence understanding of these issues, and impact other areas of life. In a discussion of the problem of talking about climate change with groups that are not engaged, or are negatively engaged, with the issue, Corner and Clarke (2017) formulated five principles for public engagement on which new initiatives and campaigns can be built. Of these, one principle seems particularly appropriate to our area of work. This is:

Principle 3: Tell new stories to shift climate change from a scientific to a social reality (Corner and Clarke 2017, vi).

Archaeologists are often particularly good at constructing social stories out of data and relating our findings to lived experience. The ability to extrapolate from community-collected data about the past to historical context for modern day 'wicked problems', and emphasising the local significance, is potentially one of the greatest areas of relevance of our specialisms to the modern world.

Surveying a small number of community groups and specialists has revealed positivity towards the idea of cooperation between the two groups, and that there is already some interaction underway. However, it has also revealed that some community groups are not sure who to contact for help with palaeoecological aspects of their work, and a lack of understanding exists regarding the relevance of specialist work to more recent periods and local history in general. There is already a range of public engagement work being done across the BGHP community; however, greater collaboration is desirable. This could be beneficial to the sustainability of archaeological specialisms in general, by generating more work and more data, by raising the profile of specialisms, and by increasing the potential number of future specialists. Further, wider engagement with the creation and interpretation of specialist data may impact understanding of 'wicked problems' in modern society, by providing an additional level of locally relevant historical context.

Cite this as: Law, M. 2019 Beyond Extractive Practice: Bioarchaeology, Geoarchaeology and Human Palaeoecology for the People, Internet Archaeology 53. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.53.6

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.