Cite this as: Pickering, R. 2020 Visitor Erosion in Fragile Landscapes: Balancing conflicting agendas of access and conservation at properties in care in Scotland, Internet Archaeology 54. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.54.11

Historic Environment Scotland (HES) is the lead public body established to investigate, care for and promote Scotland's historic environment. A major function of HES is to manage the portfolio of Properties in Care (PICs) on behalf of Scottish Ministers.

Conserving, managing and providing access to these historic sites can be challenging. There is often a difficult balance to strike between conservation needs and encouraging access, between commercial needs and ensuring visitor safety, while protecting the cultural significance and preserving fragile remains. This article explores some of these challenges, focusing on two case studies where increasing visitor numbers are posing a threat to fragile archaeological landscapes and the practical measures that have been taken in recent years to address this. In both cases, the threat of erosion caused by visitors has led us to reassess how we protect and conserve these sites in the long term, how we choose to present them and provide access, and to reconsider how we define, promote, and prioritise the various elements of a site's cultural significance. Both examples raise difficult questions around successful long-term management and conservation of seemingly 'wild' and 'natural' landscapes in the face of increasing visitor numbers.

There are over 300 properties across Scotland that are managed by HES on behalf of Scottish Ministers. The portfolio represents over 5000 years of Scotland's history and prehistory. These are nationally and internationally significant monuments, most of which are legally protected as scheduled monuments or listed buildings, in addition to being in state care. The role of HES is to enhance knowledge and understanding of these sites, to share and celebrate them and provide access for all, and to conserve and protect them for future generations.

Our remit in relation to the PICs is defined by two main pieces of legislation: the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act (1979), which provides legal powers to secure public access arrangements for PICs and sets out the terms for ownership and guardianship of monuments in state care, and the Historic Environment Scotland Act (2014), which sets out the terms by which Scottish Ministers may delegate functions relating to the PICs. The majority of the PICs are free to access and many are open all year round, without restriction. Our policy (HES 2016) aims to make the PICs increasingly accessible, broadening the visitor demographic and encouraging all to engage with, enjoy, and benefit from the historic environment.

Holyrood Park is the largest and most varied of all of the PICS managed by HES. It is a unique landscape in an urban setting, a dramatic and rugged open space within the heart of the city of Edinburgh. The park covers around 259 hectares and is a varied terrain, with playing fields and sweeping grassy slopes around the perimeter, and hills, rocky crags, and lochs within. The remains of an extinct volcano stand at the centre, rising to 251m above sea level. Arthur's Seat and Salisbury Crags are both iconic landmarks, visible from miles around, and, although not part of it, form a dramatic setting for Edinburgh's World Heritage Site. Of all of the PICs, Holyrood Park exhibits the broadest range of heritage values and has exceptionally high levels of visitation and use. This makes it a great asset to HES' estate and to the city of Edinburgh. However, the site also poses many challenges in terms of management, conservation and visitor access.

Holyrood Park is significant for both its natural and cultural heritage, and is recognised and protected as such through a number of different statutory designations that inform its management. In addition to its status as a Royal Park and a PIC, it is legally protected as a Scheduled Monument. There are also two separate Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) that fall within the park: Arthur's Seat SSSI covers the whole of the park; the second SSSI covers Duddingston Loch. Its complex geology supports rich and diverse plant communities, with over 350 species identified, including over 60 species that are regionally or nationally rare. Duddingston Loch is the only natural freshwater loch in the city of Edinburgh and it provides a nutrient-rich habitat that supports a wide range of species, especially breeding water birds.

As a large open space within the capital city, Holyrood Park is an important recreational resource and has been recognised as such for over 150 years. It is viewed as a place to escape, to relax, to exercise in and explore, and is loved by locals and visitors alike. Many use the park daily, for exercise, commuting or dog-walking, and climbing to the top of Arthur's Seat is viewed as a 'must see' by tourists in the city.

Holyrood Park is not just a green open space, but an ancient landscape, with evidence of human activity spanning from the Mesolithic to the present day. It is nationally significant for its history and archaeology. With the visible survival of features such as the cultivation terraces and four hill-forts, it offers a unique opportunity to experience and interpret such archaeological remains within an urban setting. Over 100 sites or features of archaeological interest have been recorded within the park (see the National Record for the Historic Environment; Alexander 1997a; Carruthers 2018).

The earliest traces of human activity are in the form of stray finds; a microlith and two arrowheads provide the sole evidence for the Mesolithic and Neolithic. From the Bronze Age onwards, there is evidence to suggest the land was settled and under cultivation – and that occupation and land use seems to have continued right through to the modern era. There is considerable evidence for agricultural activity in the landscape, with well-preserved sections of cultivation terraces on the eastern slopes of Arthur's Seat (some of which are likely to date from the Bronze Age) and rig-and-furrow of a later date (Figure 1). The cultivation terraces are among the best-preserved examples in southern Scotland and provide valuable evidence for prehistoric human activity in and around Edinburgh. There are also the remains of four Iron Age or early medieval hill-forts. Each is of different size, form and probable date of occupation; the best preserved is that on Dunsapie Crag.

From the founding of Holyrood Abbey in 1128, the park's history becomes intertwined with the abbey and the royal palace that subsequently grew up there. The land was divided between the monasteries of Holyrood and Kelso and was used extensively for cultivation and pasture. Lengths of earth and stone banks, swathes of rig and furrow and the remains of dams attest to the intensive use of the landscape. The most striking architectural remains in the park are that of St Anthony's Chapel, which stands on a rocky crag at the edge of the park, overlooking Holyrood Abbey. The chapel is associated with Kelso Abbey and is thought to date to at least the early 1400s, though evidence in the surrounding area and connections to a holy well suggest there may have been religious activity here from a much earlier date. In 1541 the land became a royal park; James V had a boundary wall constructed around the perimeter, elements of which survive today. In recent centuries, there is evidence for quarrying activity, rifle ranges, air-raid shelters, allotments and World War I practice trenches.

In the early 1800s, Holyrood Park was far from the calm, natural 'wilderness' we see today. It was surrounded by industry, with much of the park itself being actively quarried or used for agriculture. This began to change towards the mid-1800s as the government sought to address the excessive quarrying of Salisbury Crags by the Hereditary Keepers, the Earls of Haddington. By 1845, the Hereditary Keepers office had been bought back for the Crown and the Commissioner for Woods and Forests became responsible for management of the park. These changes signified a shift in attitudes towards the park, as it increasingly came to be seen as a place for recreation and leisure. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were responsible for many changes that essentially shaped the park as we know it today; five picturesque lodges were built around the edges of the park, the entrances were formalised and embellished, and a road was constructed to follow a circuit around the park. This was the start of the formal recognition of the park as a place of 'wildness' in the city and a place for the wider population to benefit from. These are still among the most valued aspects of the park today and are a key part of what makes it attractive and significant.

One of the biggest challenges faced in Holyrood Park is how to manage the impact of increasing visitor numbers. The park is a top visitor attraction in Edinburgh and one of the most visited sites in the estate. With the expansion of Edinburgh airport and favourable exchange rates, visitor numbers to the city have soared in recent years and this seems to be a continuing upward trend. There are over 3.5 million visitors to Edinburgh each year – many of whom are likely to visit the park – in addition to the probable hundreds of thousands of visits each year from residents. There have been no studies to calculate the exact number of visitors, but anecdotal annual estimates range from 0.5 to 5 million visits per year, with the exact figure most likely to be at the top end of this estimate.

Increased visitor footfall, and activities such as cycling and running, commercial dog-walking and organised training within the park is leading to the erosion of archaeologically sensitive areas (Figure 2). There is now a real risk of loss of significant archaeological deposits in certain areas.

An exacerbating factor in this is the increased wet weather and storm events as a result of climate change. Figures suggest that Scotland is on average seeing 21% more rainfall in recent years. Increased footfall leads to compaction of the soil; with heavier rainfall there is increased run-off and the compacted ground easily becomes saturated. This in turn results in topsoil being eroded and washed away. Visitors then avoid those areas where the ground is churned up, or paths have been eroded, leading to the widening of paths and new desire lines forming. The park's uneven terrain, steep slopes and friable volcanic rock make this especially problematic.

It is challenging to effectively communicate the sensitivity of this landscape. While it may appear bold, rugged and dramatic, many of the elements that make it culturally significant are easily overlooked and vulnerable to visitor impact. The archaeological remains are often not easily apparent and most visitors are unlikely to be aware of their significance. The cultivation terraces are an impressive landscape feature, especially when viewed in low, raking light (Figure 1), but we know frustratingly little about them and most visitors do not recognise them as archaeological features. The hill-forts and various earth and stone banks within the park are similarly easy to overlook, and again have not been scientifically investigated. Across much of the park there is high potential for the survival of significant buried archaeological deposits that could provide valuable evidence for settlement and use of the landscape from the Bronze Age through to the present day, but the nature and extent of such deposits is not currently known and may be at risk of erosion from visitor footfall.

HES shares, celebrates and encourages learning about both the cultural and natural significance of the park in a number of ways, through the Rangers Service (who provide outreach, education, volunteer opportunities, public talks and guided tours), fixed graphic interpretation panels at key locations, online and social media content, and a small exhibition in Holyrood Lodge. With such a huge number of visitors and a wide range of reasons for visits to the park, it can also be difficult to reach the right audiences. It is recognised than more could be done to promote this unique and significant historic landscape and that, in raising awareness, there are opportunities to promote better stewardship. However, there are limited staff resources in relation to the scale of the park and the number of visitors, making it difficult to be on hand to provide information about the significance and sensitivity of the park, other than through planned events such as guided walks, talks and tours. The addition of further fixed interpretation panels would not be a desirable approach to providing more information for visitors either, as this diminishes the sense of a wild and natural landscape.

The management regimes in place are aimed at encouraging access, while also trying to preserve and maintain the sense of a natural, wild and rugged landscape. The first formal management plan for the park was produced by Historic Scotland in 1993 and reviewed and updated in 2004. Though many of the objectives remain broadly the same, there are several factors – not least increasing visitor numbers and climate change – that mean the existing management plan is in need of considerable revision and updating to reflect the current situation. HES's Monument Conservation Unit and District Architects are responsible for conservation and management of the entire area within care. The day-to-day practical management of the park is the responsibility of HES' Ranger Service. They are also responsible for managing visitor safety, nature conservation, encouraging learning, engagement and education, managing public events, and running a volunteer programme.

There are a number of managed footpaths around and across the park. These are aimed at encouraging access, while guiding people away from sensitive or dangerous areas. The key routes provide access to the summit from the two main entrances; a route through the centre of the park, and one along the 'Radical Road' that runs below Salisbury Crags. There are difficult tensions to manage between increasing access, providing clear signage and safe routes, managing visitor flow, and protecting sensitive areas. There is a rolling programme of path maintenance on the main routes, aimed at addressing erosion issues, improving drainage, and encouraging safe access. The path maintenance itself tends to be carried out in phases by specialist contractors experienced in the management of sensitive upland landscapes (Figure 3). As far as possible, soil and stones for the path repairs are geologically matched. At present there is no strategic management in place to address visitor erosion issues beyond the maintained paths, other than encouraging visitors to keep to marked routes.

Though the park is recognised, at least within the heritage profession, for its rich cultural heritage, the archaeology is not understood in great detail. Yet in order to effectively promote understanding and appreciation of this historic landscape, we need to be able to understand it. A greater understanding of its cultural significance can also enable us to better manage the site and to protect it for future generations.

A comprehensive GPS survey of the park was completed in 1997 by the (then) Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (now part of HES). Prior to that a number of smaller scale surveys and interventions had taken place, although with extremely limited research aims and focused scientific investigation (see Alexander 1997b; Stevenson 1949; RCAHMS 1999). The probable prehistoric settlement, hill-forts, cultivation terraces, linear banks, and rectilinear enclosures are all of unknown date, and the precise function of the latter features is also unknown. While areas of the park have been mapped out according to their likely archaeological sensitivity, in many areas the archaeological potential and degree of sensitivity is not well understood. Given these gaps in our knowledge and the increasing threat of visitor erosion, since 2016 we have focused upon improving our understanding of the park's archaeology and its significance before these remains are potentially lost.

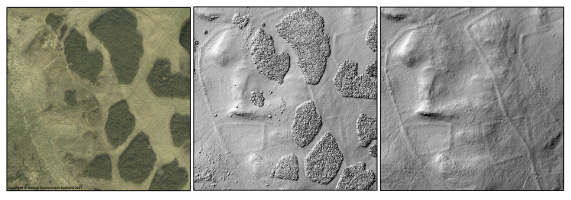

In March 2017 an airborne laser scan (ALS, also known as LiDAR) was commissioned, conducted by Blom Aerofilms, with the aim of producing a highly accurate and detailed baseline survey showing the topography of the landscape, along with high-resolution aerial imagery. This method of survey was chosen as it can detect very subtle topographic features. Another huge advantage of using ALS is that the post-processing of the data allowed us to 'remove' the dense gorse and other vegetation that covers large areas of the park, essentially allowing us to see any features that may otherwise be obscured by vegetation. This negates the need for walk-over survey, reaches inaccessible areas, saves time and costs, and has safety benefits for surveying staff.

The survey identified stretches of enclosures, earthwork banks, boundaries and cultivation terraces that are not visible or accessible on the ground owing to erosion or vegetation growth (Figures 4 and 6). New features were also identified, including the remains of World War I practice trenches dug by soldiers as a training exercise before they travelled to the front lines. The survey data has provided us with an incredibly detailed snapshot in time, allowing us to map out all upstanding archaeological features as accurately as possible, and to identify areas for concern in terms of erosion or vegetation cover (Figures 5 and 6). However, it does only provide a baseline survey and the cost of ALS at present is too prohibitive to allow regular repeat surveys for condition monitoring.

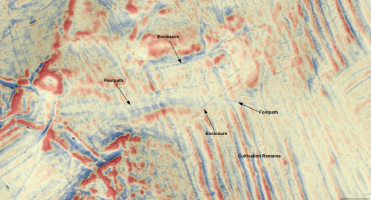

Following on from the ALS survey we commissioned CFA Archaeology Ltd to conduct a cultural heritage condition survey. The first stage involved a desk-based assessment, with analysis of all previous survey work, followed by fieldwork aimed at identifying all upstanding archaeological features visible on the ground and producing a rapid assessment of their condition, using a standardised methodology and recording form (Carruthers 2018; methodology developed from Dunwell and Trout 1999; Rimmington 2004). Where erosion or other damage was identified as impacting upon cultural heritage assets, the location and extent was recorded using handheld GPS. CFA Archaeology were able to overlay plans of the maintained footpaths and desire lines using the ALS data and the results of their desk-based assessment and field visits to evaluate areas of relative archaeological potential and their condition (Figure 7); these data can then inform how we manage areas that are most at risk. As with the ALS survey, it is the intention that the results of this project will inform a new management plan in the near future.

The condition survey identified visitor footfall as a significant factor in the erosion of archaeological features in the park and the greatest threat to their survival. Visitor footfall is having three key effects:

Visitor erosion has been recognised as an issue on the eastern slopes of Arthur's Seat since at least the 1970s, and was again flagged as an issue in the Cultural Heritage Survey of 1996 (Alexander 1997a) – though at that time erosion was localised and small scale. The recent survey (Carruthers 2018) indicated that erosion from visitor footfall has grown steadily worse in recent years, with many new desire lines criss-crossing the park. In some extreme cases, erosion is now so severe that the underlying bedrock has become exposed. The worst affected areas are around the fort on Arthur's Seat, the cultivation terraces on the eastern slopes of Arthur's Seat, St Anthony's Well, Samson's Ribs fort, and various enclosures and earthwork boundaries on Whinny Hill (Figures 8 and 9 show worsening conditions).

It is clear that visitor erosion is at an all-time high and is posing a severe risk to the archaeological remains, as well as having a detrimental impact upon the aesthetic of the park. The results of the condition survey will be used to push for new management strategies for the park – both surveys have already informed recent footpath and vegetation management. However, there is a need for a high-level and holistic management plan for the whole park that has a much wider scope than solely visitor access and footpath management. Given the complexity of the site and challenges with diminishing budgets, this is not a straightforward task. A new management plan would need to balance varied and competing needs of visitor experience, natural and archaeological conservation, and the local community, as well as taking into account consideration of economic factors and traffic management.

Case studies of other sites facing similar challenges have shown that interpretation and promotion of good stewardship can go a long way towards modifying visitor behaviour and reducing the impact of visitor erosion (Carter and Grimwade 1997; Millar 1989; McGlade 2016). Work has begun to promote the park and to raise awareness of its history, significance and sensitivity among visitors and locals alike. A new information hub was opened in 2018, re-using one of the Victorian lodges. This contains a small exhibition, explaining the significance of the park's history and wildlife, and encouraging visitors to treat the site with respect. In addition, a new leaflet is in development that outlines the main footpaths and encourages visitors to keep to newly marked routes, complemented by the addition of new signage that has been carefully designed and located so as to have maximum impact for visitors, with minimal impact upon the park's landscape. A new guidebook and audio-guide smartphone app are also in development, both of which discuss the sensitivities of the landscape and conservation work, in addition to the park's archaeology, history and natural heritage.

Discussions have begun around how to develop a campaign to promote good stewardship of the park through the use of the web, social media, and improved marketing. Anecdotal evidence suggests that engagement with local stakeholders and user groups in other parks – working with local running clubs or climbing groups for example – has resulted in notable improvements, with many visitors being likely to change their behaviour in order to reduce their impact upon sensitive areas (Martin Gray, Ranger and Visitor Services Manager, pers. comm.). The park has such a large range of stakeholders and user groups – and is such a prominent part of the city – that any future management plans will need to engage with these various stakeholders in order to be successful.

There are difficult decisions to be made regarding visitor access and acceptable loss in terms of the archaeological remains within the park. There is a need to promote core path routes and reduce access across more sensitive areas of the site. However, restricting or reducing access is far from a simple solution and it would be difficult to monitor and manage with the current resources available.

In light of the severe on-going erosion in certain areas of high archaeological potential, archaeological investigation was carried out in September 2019 focused on some of the most at risk areas. Consent was obtained for small-scale rescue excavations to determine the nature of the archaeological deposits and to gain a better understanding of the degree of impact visitor erosion is having upon these remains. The investigation also aimed to gain sufficient data through radiocarbon or OSL dating and soil micromorphology to improve our understanding of the origin, development and use of the agricultural terraces and enclosures on Arthur's Seat, before this information is lost. In addition to this, between March 2018 and summer 2019, palaeoenvironmental analysis of a loch core from Dunsapie Loch took place with the aim of furthering our understanding of the park's vegetational history and the nature of agricultural activity on the eastern slopes of Arthur's Seat. The work has been funded and managed by HES, with the specialist fieldwork and analysis undertaken by the University of Stirling.

The Ring of Brodgar is a massive henge and stone circle on mainland Orkney, situated on gently sloping ground at one end of an isthmus between two lochs. It forms part of the Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site. At the opposite end of the isthmus is the Stones of Stenness henge and standing stones, and between and around these monuments are numerous other prehistoric sites, including the massive Neolithic ceremonial centre at the Ness of Brodgar, Barnhouse settlement, and Maeshowe chambered tomb. Each of these sites, with the exception of the Ness of Brodgar, which is currently under excavation, is protected as a scheduled monument. In addition to the impressive densely packed archaeological remains, much of the land around the Ring of Brodgar is owned and managed by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) as a nature reserve.

The Ring of Brodgar is open to the public all year round, at all times. HES manages a footpath leading up to and around the monument. There is also a circular walk around the RSPB reserve, passing by the lochs either side (Figure 10). Visitors are encouraged to keep to the footpaths, and to use the two prehistoric causeways over the ditch to enter the Ring (on entry a fence directs them towards the northernmost entrance). There are no surfaced paths around the Ring at present and, until recently, visitors have been able to walk within and around the monument freely, to experience the standing stones without any restrictions (Figure 11 and 12). Though the site is managed as a visitor attraction, with signage, fencing and maintained pathways around the site, it is viewed as a wild and natural landscape and there is a desire to retain this aesthetic. The RSPB aim to conserve the grassland, heather and wildflower meadows in which the Ring of Brodgar is situated, but increasing visitor pressure also impacts upon this habitat and the many bird species that live here.

| Name of Property | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ring of Brodgar | 100,000 | 110,000 | 120,000 | 131,160 | 144,646 |

The islands have always been popular with visitors in search of history and nature – for both academics and tourists alike – but visitor numbers have risen steadily over recent years, leading to increased pressure at many of HES' PICs as heritage tourism becomes increasingly popular. The inscription of the Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site in 1999 has resulted in increased investment in visitor infrastructure and marketing, and research has been a key factor in this increase. The discovery, promotion and media coverage of the on-going excavations at the internationally significant Neolithic site at the Ness of Brodgar has also attracted increasing visitors. The rise in the number of cruise ships has been particularly significant, with huge numbers of visitors arriving on the mainland and visiting multiple sites on coach tours – especially between June and September (Tables 1 and 2).

| Period | Daily average | Monthly average | Busiest days (all recorded in August / early September) | Total visitors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 2018 – August 2018 | 936 | 28,491 | 3500 – 4100 | 100,159 |

| August 2018 – January 2019 | 484 | 14,723 | 2600 – 3100 | 73,526 |

As with Holyrood Park, increasing visitor numbers, combined with climate change – with fluctuating longer dry spells, combined with wetter summers and increased storm events – has led to compaction of the soil, waterlogging and erosion of the turf and topsoil. If left to continue to deteriorate, not only would such erosion impact upon the aesthetic and the visitor experience, it would also pose a threat to the archaeological remains themselves, potentially undermining the remaining standing stones or pushing visitors into archaeologically sensitive areas.

Erosion repair was initially carried out on an ad-hoc basis, with turf and topsoil imported and laid into erosion hollows, as and when required. A programme of path monitoring began in 2002, with a photographic record produced every two years that allowed us to identify the worst-affected areas of erosion and patterns of wear. It became evident that small-scale turf repair was not a successful or sustainable management solution. Concerns were also raised that the gradual accretion of layers of turf and topsoil could alter the appearance of the monument, potentially distorting or confusing its profile.

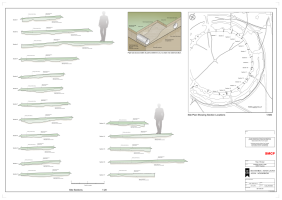

In 2011-2012 work began on a new programme of path repairs, as part of a longer term approach to managing the significant increase of visitor numbers. In 2012 a series of evaluation trenches were excavated around the eastern section of the inner ring and across the south-eastern causeway to determine the location, character, and depth of the modern accumulation of deposits; excavation continued until the earlier ground surface was exposed. Following this, the modern turf and topsoil deposits were carefully removed and a new raised turf path was created, with an inbuilt drainage system below. The design was based on a similar footpath developed for Stonehenge (Figures 13 and 14). An initial pilot section was completed in 2013, with a further stretch completed by 2015 – a year that put the new drainage to the test, with 137mm of rainfall in May and 90mm in June compared to the usual monthly average of 46mm. The extension of this approach around the whole of the inner ring continued between 2015 and 2017, until all prior turf repairs had been removed and replaced by the new raised and drained path. All of the work was conducted under archaeological evaluation and monitoring to ensure that no underlying archaeological deposits were disturbed.

Once the inner ring path was fully established, a new management regime and programme of monitoring was enacted to reduce further impact from visitor erosion. The inner ring was partially or fully closed for periods between 2015 and 2017 to allow the new path to rest and the turf to establish itself. A new route around the outer ring was signposted and additional guidance was provided by HES Rangers Services. However, closing the inner ring shifted the problem of erosion on to the outer path, leading to further damage that now needs to be addressed.

Sections of the path are now closed off, left to rest, re-seeded, fertilised and aerated on rotation as and when required. Path routes are shifted depending on predicted visitor numbers, weather conditions and turf conditions, in an attempt to diffuse the impact of visitor footfall around the Ring. On days where multiple coach groups are expected, the most sensitive areas of the site are closed and this is clearly communicated to visitors, along with the reasoning behind this (Figure 15). As much of the pressure comes from cruise-liner groups, visitor numbers can much more easily be anticipated and managed at this site, unlike visitors to Holyrood Park.

Such a management regime requires additional staff to monitor visitor numbers and conditions, enact and enforce changing path routes, carry out maintenance, and communicate with visitors. Increasing staff presence at a time of decreasing budgets, for a site that is free to access, is not without its challenges. As of spring 2019, four additional full-time assistant rangers are now in post during the busiest months (May, June, July and August), and one part-time ranger (June–August), to ensure that there is a constant staff presence on-site during the daytime. Devolving the day-to-day management of the site and supporting local decision making, rather than this being determined remotely from head office, has also had a positive impact. People counters installed in 2018 allow us to capture more accurate data on visitor numbers and patterns in visitor flow, which will also help to inform longer term management plans for the site.

In addition to these measures, HES is supporting a collaborative doctoral award in partnership with the University of Stirling, which will develop non-invasive techniques for monitoring and mapping soil moisture in archaeological landscapes. The project will focus on footpaths and visitor footfall interactions at several Scottish World Heritage Sites, including the Ring of Brodgar, to establish the extent to which visitor footfall impacts upon soil moisture, with the aim of using these methodologies to monitor and manage this site and others more effectively in the future (Hazel Ramage, pers. comm.).

Prior to completion of the new turf path and management regime, concerns had been raised by the local community about the degree of visitor erosion at the Ring of Brodgar. The strong sense of stewardship and pride in the historic environment among the Orcadian community has allowed us to work with interested parties to spread the message of good stewardship and improve understanding of the need for such conservation measures.

Alongside the path maintenance, closing, repair and re-opening there has been a great deal of careful communication about what is being done and why. Following the success of the pilot phase of path repairs between 2012 and 2015, a community meeting was held at nearby Stenness village, to discuss HES' work at the site and listen to concerns from the local community. While there was considerable discussion around the pros and cons of the current situation, there was general acknowledgement that such work was required. More recently, HES has contacted all of the relevant stakeholders informing them of the new path management regime, especially making tour operators aware that the inner path will be closed on days where there are high visitor numbers or heavy rainfall, to ensure its protection.

Increased staff presence makes it easier to get this message across and to monitor visitor flow: long-term conservation of the monument is a key part of site tours by the Rangers, who work closely with the local community, travel trade, and tour operators. New signage has been added to the site to clearly indicate when and where routes are closed and to explain why. HES has also shared posts on social media platforms, promoting the message of good stewardship and explaining the conservation work and changes in access at the site. It is a message that seems to be working; locals and visitors alike understand the significance of the site and the need to make these changes to ensure its long-term protection.

Management issues have not been confined to the inner and outer paths around the Ring of Brodgar. As visitor numbers have increased, people have spread out into the wider landscape, beyond these paths. This is generally encouraged, as it diffuses the impact of visitor footfall and allows visitors to explore more of the historic and natural landscape. However, some parts of the site have been quite severely impacted on, such as the satellite cairns around the stone circle. South Knowe – a low-lying prehistoric burial mound to the south of the Ring of Brodgar – is often climbed by visitors, oblivious to the mound's sensitivity or significance, in order to gain a better vantage point of the landscape (Figure 16). The larger, steeper sided mound of Salt Knowe is also suffering from similar threats as well as rabbit damage. These elements of the site serve as a reminder that visitor impact, conservation and management requirements must be addressed across the whole landscape and not simply confined to the immediate vicinity of the Ring of Brodgar itself.

A steady increase in visitor numbers across many of our sites in recent years has resulted in increased pressure upon these monuments and in several cases this is having a negative and potentially destructive impact upon sensitive archaeological remains. The rising visitor numbers is part of a wider trend, as Scotland has become an increasingly popular tourist destination. Certain PICs have seen visitor numbers soar after being used as filming locations on popular TV series (e.g. Outlander) or in major films (Mary Queen of Scots, Outlaw King). Both sites in this article have at least in part seen an increase in visitor numbers owing to World Heritage Site status too. At both sites, increasing visitor footfall is leading to soil compaction and erosion, exacerbated by increasing wet weather as a result of climate change. Significant changes in the management of these sites are needed if we are to successfully reduce this impact and preserve these archaeological landscapes.

Though both the Ring of Brodgar and Holyrood Park are facing similar issues as a result of increasing visitor pressure, they are not directly comparable. The Ring of Brodgar is a much smaller site and its significance as an archaeological site is more easily understood, and its social and economic value and significance is acknowledged by HES and the local community. It is also a simpler site in terms of managing visitor access, as most visitors arrive by coach, bus or car, and there are a limited number of access points and routes. The recent conservation work and changes to the management of visitor flow and access at the Ring of Brodgar has seen notable improvements to date, but it still remains to be seen if this approach is sustainable in the long term.

Holyrood Park is a significantly larger and more complex site, and the issues of visitor erosion draw us into other discussions around value and significance. Increasing visitor numbers may be threatening the archaeological remains of the park, but the majority of visitors are unaware of this significance. To most visitors, the open green space and wildlife is more widely recognised and appreciated than the site's history and archaeology. One could take this further and even argue that the social or recreational value of the park has a greater contribution towards its significance than the evidential value of the archaeological remains. However, as a nationally scheduled monument, we have a legal responsibility to protect and conserve this site.

Both examples highlight the tension between meeting visitor needs, maintaining the character of the monument, and ensuring long-term protection of sensitive archaeological remains. It can be particularly challenging to manage this impact at sites that are free to access and in open, natural, landscapes – especially at a site as extensive and varied as Holyrood Park. Improving or reinforcing path networks and increasing signage could limit the impact of visitor erosion. But limiting access, adding infrastructure, or introducing more permanent and robust path networks would also 'erode' cultural significance, by undermining the wild and natural sense of these sites, or diminishing visitor experience. There is a delicate balance to strike, and difficult decisions may need to be made in the future regarding the level of visitor access versus the long-term conservation of such properties.

There is much we can learn from examples at other heritage sites, such as Hadrian's Wall, where many similar issues are faced and there is the same need for sensitive conservation measures to protect the archaeological remains without detracting from the natural landscape. It is evident that there is a need for robust management plans, combined with stakeholder and community engagement. Promoting a message of good stewardship and educating visitors about the significance and sensitivity of the site through interpretation has proven successful at the Ring of Brodgar, and at other heritage sites around the world, and is an approach that could be implemented to greater effect at Holyrood Park.

I would like to thank the EAC board for inviting us to present this topic, and to all attendees for the useful discussion and thought-provoking sessions. I would also like to thank my colleagues and others who assisted with the development of this article, especially to Richard Strachan, Martin Gray, Stephen Watt, Karen Williamson, Judith Anderson, Stefan Sagrott and CFA Archaeology for their input.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.