Cite this as: Eres, Z. 2020 The Changing Policies on the Protection and Management of Archaeological Sites in Turkey: an overview, Internet Archaeology 54. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.54.13

The first efforts that the state in Turkey made for the protection of archaeological areas were the legal regulations launched in the mid-19th century. In the period of the Ottoman Empire, the Middle Eastern regions that formed part of the Ottoman territory, including Egypt, the Aegean coast and the Mediterranean region, had been home to many glamorous and high-profile archaeological sites, which proved very attractive to European archaeologists at the time, thus prompting them to request permission to conduct excavations in the field. Initially, legal regulations were issued on a project by project basis. In 1869, the first general legal regulation was made to manage the permissions. Modern conservation experts refer to this regulation as the first 'protection law' issued by the Ottoman State, focusing on permissions to carry out excavations, their management and control (Eres and Yalman 2013).

According to this law, the owner of the land on which the excavations were conducted could claim possession of the finds discovered during the operations. Although it was illegal to take such relics abroad, they could be bought and sold within domestic borders and the state held the principal right to buy them. However, if the Sultan gave special permission it was also possible to export the archaeological relics in particular cases (Eres and Yalman 2013; Karaduman 2004). A second law, enacted in 1874, had a broader outlook and listed the antiquities item by item with their qualities in detail. The most remarkable feature of this new law was that the relics discovered during excavations were divided between the state, the landowner and the manager of the excavation, giving one-third to each party. Owing to the fact that all the archaeologists working on the archaeological sites at the time were from Europe, this law made the legal export of antiquities into Europe possible, and was therefore revised in 1884 with a third law passed completely banning the export of antiquities abroad except by special permission of the Sultan.

These three initial laws passed by the Ottoman state identified only the archaeological remains as 'antiquities' and developed strategies for protection of these relics (Çal 1990; Madran 2002; Bahrani et al. 2011). Another law enacted in 1906 classified the pre-Ottoman and Ottoman monuments and the splendid residential buildings belonging to the period as antiquities as well. This fourth law, which by the standards of its time may be described as comprehensive, was utilised as the protection law as recently as 1973.

In the 19th century, an important decision taken in the field of antiquities regulation was the appointment of Osman Hamdi Bey as the director of Istanbul Archaeology Museum in 1881. Osman Hamdi Bey was one of the prominent figures of the era. His truly versatile profile as an artist and archaeologist was recognised and respected in the world of arts and sciences. He worked hard to enrich the Ottoman imperial museum with an expanded collection of antiquities, and launched the first Ottoman excavations (Shaw 2003; Eldem 2010; Özdoğan 2019). On the one hand, the museum made appeals to the far corners of the empire to send their antiquities to the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, while on the other, new archaeological excavations were organised, such as those at Mount Nemrut (1883) in South Eastern Anatolia, Sayda (1887) in today's Lebanon, and Lagina (1891) on the Aegean coast (Bahrani et al. 2011; Özdoğan 2019).

The initial efforts by the Ottoman state mentioned above are limited to the protection and the possible exhibition of 'archaeological antiquities', rather than 'archaeological sites' as a whole. In those times, the formation of Imperial museums to exhibit antiquities imported from different parts of the empire was considered a necessary part of the process of Westernisation, or, in other words, modernisation. In this sense, it might be difficult to claim that the Ottoman state was seriously concerned about exhibiting/presenting the antiquities to its own society. That said, an interesting point worth emphasising is that the 2nd Antiquities Regulation of 1874 included an item specifying that a special state officer would be appointed at some temples, which were defined as having 'perfect qualities'. Although this clause was not frequently practised, it reflects an awareness of the need for protection in situ. If we consider the fact that the 2nd Antiquities Regulation was prepared by the Museum Director Dr Anton Phillipp Dethier, this approach may be interpreted as a result of his sensitivity.

Founded in 1923, the Turkish Republic emphasised the importance of archaeology in order to better define the modern identity of the new state, differentiating it from the Empire of the past (Özdoğan 1998; 2019; Eres 2016). In Turkey, in addition to the new regulations made in the legal, institutional and economic realms, all of which bear the hallmark of being a revolution on its own, education and culture also went through a process of reform, because they were determined as the key elements for the sustainability of the new regime. In this sense, it may be stated that a 'cultural revolution' was also targeted during the formation of the Republican structure, and it has been underlined during the modernisation process of the society as a whole. In addition to the development of the Turkish language, there was renewed focus on the development of archaeology. Thanks to this approach, which was strengthened by Atatürk's personal interest in archaeology, French archaeologists were allowed to excavate in the ancient city of Teos in 1923. During this era, the establishment of foreign archaeological institutions was allowed. Permissions were given for many archaeological excavations led by foreign teams. Moreover, Turkish researchers were also urged to launch excavations in many different parts of Turkey.

In all these reformative processes, the main objective was to reveal various periods and different cultures, and demonstrate the significant role played by Anatolia in the formation of cultural history by the use of scientific data. In terms of historiography in the Turkish Republic, the presence and roots of the nation have both been defined with direct reference to the history of the Anatolian land. Instead of establishing a romantic cultural context for Central Asia, the history of Anatolia was adopted as a common past.

During the first years of the Republic, archaeological excavations were encouraged and organised with the aim of discovering the Hittite, Urartian, Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantium times (Özdoğan 2019). In 1934, Atatürk visited and was highly impressed by the Pergamon Asklepion ruins and asked the officers to turn it into a museum. The open-air museum was launched in 1936, constituting the first example of archaeological site-based museums in Turkey.

Another intriguing and pioneering project of the time was the urban archaeology work carried out in the aftermath of the selection of Ankara, located in the mid-Anatolian region, as the capital city of the newly founded nation-state instead of Istanbul, the former capital of the Empire. The new capital was founded on the southern part of the historic city of Ankara, which was originally situated on the outskirts of a hilltop castle, and was planned according to modern principles of urbanisation. Meanwhile, excavations were also being conducted on tumulus structures and Roman archaeological sites in the region. In the aftermath of these rescue excavations, which opened-up new horizons at that time, newly discovered Roman baths were taken into protection and excluded from lands being opened to development. These baths were subsequently exhibited as an open-air museum (Figure 1).

The Early Republican era is the time when the initial efforts and applications in the fields of archaeology, urban archaeology, their protection and exhibition to the public, were defined as planned governmental policy. To sum up, this period was the time when scientific research gained significance, whereby the roots of the cultural history of the country was emphasised and verified through archaeological excavations. In this period, both national and non-national researchers were encouraged to launch and develop scientific projects. However, owing to the nationwide and global economic recession of the time (the Great Depression) and a paucity of skilled professionals, there was a discrepancy between the archaeological conservation aims and what was actually achieved, in terms of both quality and quantity.

World War II began shortly after Atatürk's death. Although Turkey resisted involvement, the country also suffered owing to worldwide economic crises and shortage of resources. In the bipartite world system that followed the war, Turkey furthered ties with the USA in the 1950s. The country's economy developed in the context of strong ties and dependence on foreign resources, while the archaeology in the country exhibited a more parochial attitude towards current world news. Though a small number of national and foreign excavations were carried out, neither the archaeologists nor the relevant ministry (General Directorate of Antiquities and Museums of the Ministry of National Education) developed a vision or policy in terms of protecting, exhibiting and presenting these areas to the public (Özdoğan 2008; 2019; Eres 2016; Eres and Özdoğan 2018).

Perhaps the most remarkable project of the time was the work of protection and restoration that took place in the 1950s inspired by the Karatepe-Aslantaş excavations in the Adana Region. Through a series of work carried out by the head of the excavation, Halet Çambel, in co-operation with Central Institute of Restoration in Rome managed by Cesare Brandi, the results achieved were rather innovative by international standards (Eres and Özdoğan 2012; 2016; Eres 2016). Fragmented pieces of the stonework, bearing inscriptions and ornamentation, were brought back together and restored in situ. This was made possible by the construction of a protective roof, which was one of the first examples of its kind throughout the world (Schmidt 1988) (Figures 2 and 3). In addition to implementations aimed at protection and exhibition of archaeological remains in situ, there were significant and pioneering efforts to create public awareness in the local communities. This was achieved by providing the neighbouring villages with primary education and economic support by developing projects for raising the villagers' living standards, thus enabling the village communities to adopt sustainable models for conservation.

At that time, the archaeological site at Karatepe-Aslantaş was situated in a remote area, completely off the beaten track and away from tourist attractions. In this context, it is noteworthy that the focus was on societal benefits and not on tourism. Furthermore, during the 1970s, anastylosis works gradually began at ancient archaeological sites along Turkey's Aegean and Mediterranean coasts (Schmidt 1993). The restoration of the Library of Ephesus Celsus arguably reflects the most outstanding example in the archaeological history of Turkey, leaving a memorable mark on society's relationship with archaeology (Figure 4). On the other hand, the re-erection of Sardes gymnasium in the late 1960s, with an insensitive reconstruction, has been widely criticised (Figures 5 and 6). In summary, during this period, archaeologists as the directors of the excavations carried out anastylosis or reconstructions at many archaeological sites, which led to selected monuments to stand out among the ancient ruins. It may be incorrect to state that anastylosis of certain monuments had the sole aim of exhibiting selected monuments to the general public. These projects also provided archaeologists with opportunities for experimental processes through which they gained experience, developed new perspectives and broadened their horizons. However, during this period, there was no approach to develop conservation and exhibition strategies for an archaeological site as a whole unit. However, in areas such as Ephesus, which have been excavated for more than a century and where the magnificent marble roads in the city were exposed, these roads were considered as self-excursion routes. Another remarkable intervention from this period relates to the Roman baths, discovered during archaeological excavations at the ancient site of Side. The walls of this structure were covered with a reinforced concrete vault and, thus, the bath was turned into a museum (Atik 2011) (Figure 7). There is no doubt that this operation may be considered a harsh intervention of restorative work.

This period may be generally defined as a time when some conservation and exhibition projects were initiated by the valuable efforts of archaeologists themselves. However, the actual governmental institution that has responsibility for such protective measures, namely the General Directorate of Antiquities and Museums, focused its energy and motivation towards more legal and executive regulations. An important step taken in this period was the introduction of the concept of 'registration of antiquities', with a special law enacted in 1973. The historic monuments, ancient ruins and archaeological sites that were indirectly protected at the time, were now to be protected under this new legislation.

However, the system, which has no field organisation and tries to maintain protective efforts simply by allocating human resources that consist solely of museum officers, could not play a sufficient role to protect heritage. The exhibition of archaeological sites and their presentation to the public were also regarded as having secondary importance compared to the larger umbrella of tourism, which began to grow in the 1970s. In this period, issues such as community and cultural heritage, or the creation of public awareness, were not on the agenda of the governmental institutions responsible for the protection of archaeological heritage.

The 1980 coup d'état in Turkey has led to rooted changes in the governmental and societal structure of the country. In a very short time, Turkey adopted a rather neoliberal economic system, in which global capital gained utmost importance. With this radical change, everything began to evolve in a different manner and pace. The renewal of all forms of infrastructure in Turkey, with support granted by foreign countries, foreign intervention and co-operation in the foundation of technical systems in the fields of banking, stock market and the economy, the rapid growth in the construction sector changed both the economic system and the general appearance of the country as a whole. This period may well be described as a highly innovative one, which has raised living standards with the construction of highways, bridges, dams and increasing urbanisation. However, it was also a time when historic environments and all types of cultural heritage were largely destroyed.

On the one hand, a new law entitled 'Conservation of Cultural and Natural Property' was issued in 1983, in accordance with similar laws in other parts of the world. On the other hand, an intensive development plan was launched, which eventually led to the destruction of cultural heritage across the country. This law was based on protecting the 'registered' cultural heritage only. However, since the Ministry of Culture and Tourism has not registered all the cultural monuments across Turkey, many historic buildings and settlements had no legal protection (Eres and Yalman 2013; Eres and Özdoğan 2018).

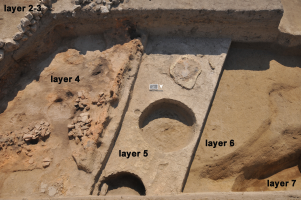

All in all, the total effect of this era on archaeological sites was destructive. Turkey is situated on land that spreads across 800 thousand square metres and both the Anatolian and Thracian areas embody many archaeological sites of various types. Large ancient ruins, prehistoric mounds, tumuli, flat (single-layered) settlements and caves require a wide range of protective measures. Mound settlements in particular, with diameters of 2km and heights of 50m, bear millennia of archaeological-rich urban formation layers, dating back to early periods (Figure 8).

In rural areas, while many large-scale projects such as highways and dams were being constructed (Özdoğan 2013), the unregistered archaeological sites in the region were flooded with water or were made available for construction. In addition, the urban areas were similarly being made available for construction without enough investigation into the possible presence of any underground archaeological ruins; the urban areas were uncontrollably damaged by construction despite the historical ruins and mounds, which eventually led to a high degree of damage to the archaeological layers that existed below the ground (Özdoğan 2013).

The 1990s was a period when European Council and ICOMOS began to prepare specialised charters to protect different types of cultural heritage. In terms of archaeology, the ICOMOS charter for the Protection and Management of the Archaeological Heritage (PDF), launched in 1990, forms the basis of the text of the European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage (1992, Valletta Convention). Other important steps taken on the way to protect the archaeological heritage are the ICOMOS International Cultural Tourism Charter: Managing at Places of Heritage Significance in 1999 (PDF) and the Cultural Routes Programme of the Council of Europe in 1987 (Eres and Özdoğan 2018).

In terms of archaeology, Turkey has incorporated the Valletta Convention into its legal system, having signed it in 1999, which bears ultimate importance due to its having legal binding force. Nevertheless, the legal rules may not always be put into practice, and not everyone goes by the book. For a long time, Turkey has only carried out archaeological research within public projects funded by international investment communities or the World Bank, due to the demands made by these investors or funders. For instance, the dam projects of the Euphrates River along the Turkish border, natural gas projects that extend to all corners of Anatolia and the subway projects in Istanbul, were instances where such regulations were put into practice and archaeological excavations took place beforehand (Özdoğan 2013; Karul 2013). However, all across the country, many other infrastructure projects were permitted and implemented without any detailed investigation of the archaeological heritage. That is why we are not completely aware of how many archaeological monuments or deposits were destroyed.

Extensive archaeological excavations were held in advance of the developments, having been encouraged and even recommended by the international system in many instances, including the subway construction in the downtown area of Istanbul. These efforts have made it possible to reach new archaeological discoveries that would change both the urban and regional history. In many districts of Istanbul (Üsküdar, Sirkeci, Cağaloğlu, Yenikapı, Beşiktaş, Haydarpaşa, etc.) rescue excavations have revealed extensive archaeological areas of thousands of square metres and up to 20 to 30m in depth (Karamani Pekin 2007; Kocabaş 2010; Başgelen 2016). These excavations in Turkey, within the framework of the Valletta Convention, are successful operations. Nevertheless, such efforts are still not sufficient in terms of achieving the right kind of exhibition and presentation of the findings to the public. The display of cultural assets unearthed by rescue excavations in urban areas and their presentation to the public is still at a preliminary stage in Turkey. On the other hand, during the last decade, attempts to exhibit and present archaeological sites have dramatically increased, and many projects have been developed. The study presented in the rest of this article deals with the conservation and presentation projects of archaeological sites located in rural areas and the changes in attitude of both the State and archaeologists in present-day Turkey, both in terms of conservation of archaeological sites and their presentation to the public, and in terms of societal expectations.

The above-mentioned review of the protection of archaeological heritage in Turkey has clearly indicated that the processes in this field are mainly dominated by decisions taken by the State. The central government has a voice in all archaeological sites, accompanied by heavy bureaucratic regulations imposed by governmental institutions, including the regulation of excavations and auditing the sites. The second authority holding power over archaeological sites is made up of excavation directors. The Conservation of Cultural and Natural Property law enacted in 1973, and amended in 1983, largely covered the regulation of excavations and, with the special permission granted by the Board of Ministers, archaeologists who received permissions were given the official title 'excavation director'. With this entitlement, the directors held the right to manage excavations, protect the sites in the way they would like to, and issue scientific publications. In practice, until the early 2000s, archaeologists undertook excavation, research and conservation projects in the context of their own approach. The above-mentioned examples at Karatepe-Aslantaş, Hattusha, Çayönü, and Side were developed by the individual efforts of conscientious archaeologists who were responsible for the excavations. Between the 1950s and early 1990s, the regulations issued by the Ministry of Culture primarily covered the restoration of monumental buildings and the protection of historic urban settlements. What is actually expected from the 'Protection of Cultural Property Boards', which have been formed by the Ministry, is the registration of cultural properties and historic urban settlements, in order to protect them under the law. The Protection of Cultural Property Boards are also supposed to grant the permissions for restoration projects of monumental buildings and to regulate the city development plans of urban conservation areas. Thus, until the 2000s, there were practices that were handled only by archaeologists who were sensitive to issues such as conservation, exhibition and presentation to the public, and were mostly independent of the bureaucracy of the Protection of Cultural Property Board.

The 2005 Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (Faro Convention) and 2008 ICOMOS Charter on the Interpretation and Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites are two international regulations that essentially cover the issues of protection and exhibition of cultural heritage to the general public. In terms of archaeological heritage, this issue was addressed by many different types of regulation since the 1956 'UNESCO Recommendation on International Principles Applicable to Archaeological Excavations', and only since 2000 have new regulations formed the main framework to provide the appropriate protection for archaeological heritage. In fact, in the 1950s in Turkey, the approach developed by Halet Çambel was a good example that illustrated a multi-dimensional and holistic attitude towards protection, and might be listed as a pioneer effort in terms of its early date. However, it took a long time for Turkish archaeologists and state officials to take this approach as a model for both domestic and foreign excavations. For a very long time, Karatepe-Aslantaş open-air museum was regarded solely as a one-off project resulting from the enthusiasm of a single archaeologist. However, Peter Neve was impressed and he launched a project to protect and exhibit the Hittite city of Hattushas in the late 1970s (Figure 9) (Neve 1998). Thanks to these efforts, this site was included on the World Heritage List in 1985. Subsequently, Mehmet Özdoğan, a student of Çambel, developed a protection and exhibition model in the early 1990s at Çayönü, in south-eastern Anatolia, and in the late 1990s at Aşağı Pınar and Kanlıgeçit in Eastern Thrace (Özdoğan 1999; 2006; Eres 2016) (Figures 10-13). As a matter of fact, in the 2000s, archaeologists coming from various schools of education started to develop conservation and exhibition projects in different parts of the country. The approach to preserving archaeological sites and their proper display to the public eventually became widespread in different regions of the country, launched by various scientists and experts.

An important point to emphasise is that the conservation work maintained in proto-historic or prehistoric sites in Turkey (mentioned above) and the work implemented at the ancient sites belonging to Hellenistic-Roman culture bear significant differences (Eres and Özdoğan 2018). In the multi-layered archaeological sites, most of which are in the form of mounds, and in those sites that show no above-ground indications of ancient ruins, archaeological deposits are uncovered during excavations. It is very difficult to preserve the architectural remains in such archaeological areas, where we may find multi-layered forms of stone, adobe or wattle-and-daub architecture (Figure 14). What is more difficult is to ensure that the visitor can correctly perceive the archaeological site. Therefore, the experts working on such places try to find solutions specific to the site they are working on, by taking its opportunities and weaknesses into consideration. In situ presentation of architectural remains under a protective roof; the sealing of the remains under soil and the construction of their models on top; the presentation of a single period or selected periods for the multi-layered archaeological sites; reconstructions created within or near the site, are just some of the methods used to achieve this (Eres and Özdoğan 2012; Eres 2016).

On the other hand, when we consider ancient sites where Hellenistic-Roman cultural heritage has been discovered, the situation is rather different. First of all, these sites embody ruins that are visible and in situ. At the sites where archaeologists run the excavations, ruins made of marble or other types of stone are revealed and these types of ruins may well be preserved in outdoor conditions with ease. They do not require any type of special project development. At these sites, what is especially challenging for archaeologists is how to display ceiling mosaics and wall frescoes, both of which are difficult to preserve in outdoor conditions. Archaeologists who desired to create a more comprehensible and visual space for the visitors, opted for techniques such as anastylosis, just as they have always done since the beginning of the 1800s (Schmidt 1993; Jokilehto 2002). These types of work have been gradually initiated by excavation directors since the 1960s during the excavations along the Aegean and Mediterranean coasts of Turkey (Eres 2016).

The 5-year tourism development plan (1973-77) introduced the creation of mass tourism within the country, which was identified as one of the biggest sources of GNP (gross national product). That is why, in the aftermath of 1980, when the country became influenced by a more neoliberal economy and global system, mass tourism also became orientated towards beach holidays. Along the Aegean and Mediterranean coasts, which have always been the main centre for beach tourism, the Celsius Library of Ephesus and other column rows situated along royal roads at ancient sites were presented to tourists as the 'cultural sauce' of their seaside holiday (Eres and Özdoğan 2018).

Until the beginning of the 2000s, the beach-orientated emphasis of mass tourism led tourism authorities to believe that the erection of ancient buildings by using anastylosis was sufficient for the presentation of archaeological ruins to the tourists and the general public, and this implementation was usually initiated by the directors of excavations. The royal marble roads usually paved the way for the tourists inside the ruins, and the rows of columns and temple façades were considered an adequate reflection of the glamour of ancient Hellenistic-Roman times. In the archaeological sites, there was no holistic approach to preserve and exhibit the ancient city as a whole. In this sense, the model developed by the Sagalassos excavation team in early 1990s and the modern approach that they adopted led to a rather elaborate implementation of anastylosis specific to this site (Waelkens et al. 2006).

Rooted changes that took place in the State's approach to the preservation and presentation of archaeological sites in Turkey began in 2000. As we have seen, prior to that, the main concern of the State was to regulate archaeological excavations and to make the necessary legal and executive arrangements in order to prevent the illegal exportation of archaeological objects. However, as the new millennium began, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism added the restoration of archaeological heritage to its official programme, and within a very short time, they began to allocate funds for the restoration of archaeological heritage by assigning the appropriate contractors, using the method of bidding. This was the first time that, independent of the directors of excavations, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism developed restoration works at archaeological sites. In these types of restoration project, the excavation directors were sometimes consulted during the restoration work. However, the decisions regarding what type of intervention would be made at any given site were now taken by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

This change in the State's approach basically derived from the need and desire to open up new areas for tourism in Turkey, and to integrate the concept of cultural tourism into seaside tourism, which had become one of the essential forces of the Turkish economy. The general opinion was that the more they applied techniques to re-erect monuments through the method of anastylosis, the more the sites would become attractive for tourists. In 2004, new legal regulations made it possible to fund the preservation of cultural heritage through nationwide real-estate profits, which overcame the difficulty in funding and budgetary constraints for such projects. In 2010, further legal regulation made it obligatory to get approval from the Protection of Cultural Property Board for the initiation of any kind of architectural projects that involved restoration work at certain archaeological sites. As a result, there was a transformation in the processes, whereby the architects who won the bid to run projects now formed teams of construction engineers, material experts, etc., and managed the projects by special permission from the State. Although this approach may seem to be more professional, because there were insufficient architects in the country proficient in running conservation projects, many projects were managed by unskilled staff, with a 'doing the best we can' type of approach.

In the conservation projects defined by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, numerous technical experts from a variety of disciplines play a role in a given project, which may be based on detailed technical analyses (related to material, deterioration, etc.). Although a number of these projects pose technical problems, some of them prove to have applied sympathetic and qualified restoration work. However, in terms of the archaeological conservation practices of the Ministry, the main issue to be discussed is the theoretical dimension of the project. The erection of a monumental ruin in any archaeological site by the use of a reconstruction technique that exceeds the rules of anastylosis and leads to controversies does not meet the archaeological principles listed in the Venice Charter (PDF). The monumental structures that were completed with no holistic approach but by making 'predictions' ultimately create an artificial aspect to the archaeological site. In the last few years, the State, as well as some academics, prefer to re-erect the archaeological buildings even though insufficient of the structure survives for a proper anastylosis (Figures 15–17).

In any type of archaeological site, the development of a holistic project that covers the entire site, planning for preservation and presentation should include short-, middle-and long-term goals. The conservation work should be gradually developed by taking the unique features of each piece into consideration. More importantly, the excavation work on an archaeological area should be done with the ultimate purpose of emphasising the importance, meaning and value of that settlement in cultural history, achieving new findings and revealing new types of information. The main incentive for initiating such work should be, above all, scientific. Planning excavations solely for the purpose of presenting beautiful and attractive monuments to the public purely for economic reasons would not be the right step to take. In this sense, in some excavations managed by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, all the projects to open up new archaeological ruins in order to make the site more 'visible' and attractive to more visitors will become problematic in the long term. Although the visitors will leave the site with good impressions, the site will also have serious preservation problems in the medium term. In conclusion, the anastylosis projects that are based on intensive excavations and reconstructions aimed at increasing tourist demand by creating aesthetic impressions will culminate in various problems that require the attention and decision-making of the experts as new issues arise in the future.

Having said that, when we consider the actions of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, especially since 2010, it may be noted that the expropriation of large ancient ruins and their removal from private ownership has been a positive step towards the creation of a more reasonable protection plan. In this way, the burden is lifted from individuals who possess a property or land within the borders of an archaeological site, and the tension between the State and the local community is eliminated. The government has begun to give more importance to large-scale planning, and projects are prepared with the title 'Landscaping Plans', covering the archaeological site as a whole. A tourist route is being designed in every detail and the tourist information centres at the entrance to the sites provide all the information a visitor needs. At larger historic sites, plans are being made to establish a museum at or near the site, so that the site is directly exhibited. Although these exhibition and protection processes still pose a range of problems, it is highly significant that the Ministry of Culture and Tourism has been making a range of efforts with the objective of protecting, exhibiting and presenting archaeological and heritage areas (Eres 2016).

There is no doubt that, in order to avoid irreversible damage that may occur to archaeological sites, international regulations should be considered and an independent auditing system should be followed, inspected and reported by international experts in the field – perhaps with an infrastructure based on NGOs. Interestingly, such a system gradually began to form through the media. In recent years, media coverage has been highly effective in highlighting incorrect and unqualified restorative works. Therefore, when a controversial restoration attracts media attention, those responsible for the project have even tried to organise scientific symposiums in order to explain their objectives.

As for the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, an important change that they have undergone in terms of archaeological heritage is participation within UNESCO's World Heritage List. Having signed the convention in 1983, Turkey has begun to take part in the World Heritage List with various elements of cultural heritage since 1985. In those years when the government was reluctant to engage in detailed protective measures, such as having a site management plan, Turkey succeeded in making its archaeological work become part of the List. Between 1985 and 1998, five out of nine sites are defined as archaeological areas, all of which were reported to have been excavated by foreign teams. Archaeological sites in the World Heritage List during this period include: Hattusha, Mount Nemrut, Hierapolis, Xanthos and Letoon, and Troia. In addition, the 'Göreme National Park and the Rock Sites of Cappadocia' and 'Historic Areas of Istanbul' World Heritage sites also contain archaeological sites. A common feature of these sites is that their outstanding international universal value in cultural history is in no small part a result of long-term excavations, research and publication. The introduction of site management into Turkey's legal system and the increase in necessary staff have taken a long time. In 2005, however, the required regulations were adopted to make site management obligatory for archaeological sites. Nevertheless, the low number of proficient experts has prevented the consistent implementation of these processes in all regions of the country.

Since 2010, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism has regarded the integration of national cultural heritage into the World Heritage List as a matter of prestige, also viewing the profit made in this respect as an important revenue source for the national income. Today, eleven out of eighteen World Heritage Sites in Turkey comprise archaeological sites.

All the efforts made by different agents for the improved interpretation, exhibition and presentation of archaeological sites are undoubtedly precious for the protection of historic heritage in the long run. The protection of an archaeological site cannot be maintained just with the legal and executive authority of the state. In today's world, it would be unrealistic to believe that a protection programme that does not involve the participation of related vocational organisations, local administrations and a considerable part of society would be permanent and 'sustainable'. In this sense, the Faro Convention (2005) and ICOMOS Charter on the Interpretation and Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites (2008) are the international regulations that aim to embody cultural assets for the community and identify the ethical codes. However, the protection, preservation and presentation of an archaeological site need to be scientifically informed from the outset.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.