Cite this as: Griffiths, S., Edwards, B. and Reynolds, Ff. 2020 Public Archaeology: sharing best practice. Case studies from Wales, Internet Archaeology 55. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.55.1

The historic environment of Britain includes rich and diverse sites and landscapes, with materials and archives curated by a range of organisations. This project came about as a review of public archaeology across different historic environment sectors in Wales, in order to understand how public heritage best practices are developed across different regions. We are focusing here on public archaeology, as a form of public heritage discourse, which has the broad scope of practice and scholarship where archaeology meets the world. We discuss definitions of public archaeology below, and contrast public archaeology with community archaeology, which tends to draw a distinction between top down/bottom up approaches.

There are many stakeholders in public heritage – some of specific relevance to different national or regional concerns –including those working in museums, on archaeological excavations, in survey work, for national organisations, in local societies, and in many other settings. Public heritage work in Wales offers a specific series of concerns, including economic conditions, the post-industrial history of the country, the importance of Welsh language and Welsh medium delivery, the structure of cultural heritage and historic environment management in Wales, the issues of engaging diverse communities, as well as the country's geography and infrastructure. This project was designed to provide a forum to discuss and share best practice, identify specific concerns within public heritage in Wales and how best practice could be developed with reference to a range of relevant case studies.

The project used a series of structured interviews conducted with the Welsh Archaeological Trusts (Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust, Dyfed Archaeological Trust, Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust and Gwynedd Archaeological Trust) to assess the scope of public archaeology in Wales, and the results of a conference session held at the Theoretical Archaeology Group in Chester in 2018, to identify current practice in terms of activities, output and legacy in Wales. We also present a critical analysis of our own public archaeology research project undertaken as the 'Bryn Celli Ddu public archaeology landscape project'.

The management of the historic environment in Wales is unique in Britain. The regional trust system in Wales contrasts with the rest of Britain. In Wales, four Archaeological Trusts are supported by grant-aid funding from Cadw in order to undertake a number of roles, including maintaining Historic Environment Records, providing curatorial advice in advance of development, and to provide the context for facilitating and delivering public archaeology. This funding structure embeds a strong regional public service ethos that is at the core of the Trusts' charitable objectives. This is in contrast to the system of developer-led archaeology in England, for example, where professional archaeology units can understandably find it challenging to deliver public archaeology programmes in a developer-led context. This unique funding model can be identified as one of the most significant strengths of the management of the historic environment in Wales.

As well as the public archaeology work undertaken by the Trusts, numerous other organisations undertake projects with communities across Wales. This includes Cadw itself (for example as part of the Unloved Heritage? Project, see below), the university sector (for example Manchester Metropolitan University with Cadw at the Bryn Celli Ddu Public Archaeology Landscape Project, and the National Heritage Lottery funded work by Cardiff University at Caerau Hillfort), the museum sector (for example the National Museum at the Llanstadwell Chariot Burial in Pembrokeshire) and the role of the many smaller voluntary societies across Wales. These smaller societies include organisations such as the Cambrian Archaeological Association, with their active programme of lectures and visits. The context of public archaeology in Wales is therefore distinct from the practice in the rest of the United Kingdom.

In 2013, the Cadw Community Archaeology Framework defined a range of aims for community archaeology in Wales, including:

In the Framework, the aims of community archaeology were defined as:

This series of aims is notable for its ambition and wide-ranging scope. The portability of these aims is also notable; these could equally be applied internationally to many countries beyond Wales. Within these aims, the key phrases might be identified as 'involvement', 'achievable' and 'build capacity'.

Cadw defines the scope of community archaeology slightly more narrowly, as 'archaeology initiated and driven by communities' (Cadw 2013, 2). In the 2013 document, Cadw recognised public archaeology as a much broader concept. The deliberate use of this term 'community archaeology' was employed to emphasise the importance of communities in leading and conceiving projects themselves. Aside from this specific valorisation of community-led projects in the Cadw document, public archaeology definitions have been more open in other parts of the heritage sector. Moshenska (2017, 1) has defined public archaeology as practice and scholarship where archaeology meets the world. Our research suggests that the social context in which public archaeology work takes place is vitally important to practice, and suggests that public archaeology is:

Archaeology in the world: negotiated, contested, ethical, and diverse, but work that makes explicit reference to the context of practice

We think that a key, but subtle difference between public archaeology and community archaeology is that public archaeology involves more critical reflexive consideration of the politically context of archaeological practice. Public archaeology is undertaken in the world, as a form of engaged practice.

Since the 2013 document, the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 provides public archaeology programmes in Wales with a distinct opportunity to work better with people, communities and each other, to address and prevent problems. Most obviously public archaeology has the potential to address long-standing health and education inequalities, both for members of the public already engaged with archaeology through local societies, and with those of the public who would like to improve their well-being through becoming engaged in archaeology. In the future, public archaeology projects would be uniquely well placed to develop a response to local community concerns (as emphasised in the 2013 Cadw document), and to develop emphasis on future well-being (as outlined in the 2015 Act).

The results of the structured interviews were collated and synthesised, together with critical reflections on our own practice. When reading these collections a series of themes emerged in terms of strengths in public archaeology, and challenges in public archaeology practice.

We identified themes in terms of the practitioners of public archaeology, the diversity of activities and undertakings, the ethical context of practice in terms of working with members of the public, the ways in which in cross-agency collaborations occurred and networks existed for sharing best practice.

A common response from the structured interviews was that the members of staff who work on public archaeology projects are key to their successful delivery. Respondents identified essential personal qualities for public archaeologists as: communication skills, enthusiasm, charisma, character, gravitas, and people with personality. The best public archaeologists were identified as people who were able to communicate with non-specialist members of the public without talking down to them. In Wales this includes, in some areas, an essential ability to communicate bilingually in Welsh and English. In urban areas, the presence of diaspora populations highlighted the need for other language skills, including for example Polish. This has been evident in practice in post-industrial landscapes engaged with by members of the Unloved Heritage? Project. The best public archaeologists are people who engage with these projects and are committed to them 'beyond a tick box exercise for strategic project development'. In order to run public archaeology projects successfully, the range of skills required – beyond traditional archaeological specialisms – is striking, and includes project planning, marketing, blogging, social media, delivery and evaluation; excellent public archaeologists have highly specialised skills. This is evident from many case studies, but especially apparent, for example, in the integrated approach to schools delivery from the Tŷ Mawr Hut Circles, Holyhead delivered by Gwynedd Archaeological Trust.

In order to develop long-term, embedded, public archaeology traditions and legacies beyond individual projects, and develop audience engagement over time, good commitment to public archaeology include a range of archaeology and activities developed with members of the public. These are recognised to include a clear sense of obligation to members of the public beyond 'traditional' archaeological skills-based training such as drawing plans, taking record photographs and so on. This should include communication about the development of the project, including its publication and dissemination, and could include for example information about the wider practice of archaeological research in the developer-led and university sectors. This includes an obligation on the part of organisations conducting public archaeology projects to include members of the public in aspects of their 'soft' organisational culture, such as social activities and news briefings. Such approaches emphasised a 'person-centred' approach to training and engagement, within an overarching commitment to the ethical treatment of members of the public working on public archaeology projects.

Central to ethical practice is valuing members of the public, and members of the historic environment community. Most obviously, this includes a commitment to health and safety training, and good practices while undertaken public archaeology projects. However, best practice is recognised as going beyond this, and including commitments from organisations delivering public archaeology to ensure the well-being of members of the public, both in terms of their physical and mental health. This should include commitments to equality and diversity, and a consideration of barriers to participation that may exist in order to encourage access from different ethnic communities, different socio-economic backgrounds, and different language communities. Consideration should be made of how LGBTQ+ people are included. Projects should consider how they can open up access and work with people of different abilities to enable volunteer archaeologists. The impact of intersectional identities and the barriers to participation that accompany these identities should also be considered. Because all public archaeology projects will be distinct, the ways in which different communities are engaged in projects will be diverse, should be creative, and should be reviewed over project lifecycles. The long-term support evident in the St Patrick's Chapel Excavation, run by Dyfed Archaeological Trust was identified by volunteers and members of the public, as an example of this ethical, engaged practice.

There is a recognition that strong and far-reaching projects can be created by individual organisations, but many projects benefit from inter-agency partnerships. These offer the ability for diversity in practices, in audiences, and offer practical solutions in terms of adding value in skillsets of practitioners and open up the funding landscape. Benefits in terms of effective project management and evaluation were also recognised, as well as the potential for fertile ground for collaboration in project delivery. Over the last five years, the Welsh Trusts have collaborated with over 75 external partners in delivering public archaeology projects (excluding all schools and heritage agencies). These external partners can be classified as local organisations, national organisations, third sector organisations, government organisations and environmental organisations, as well as heritage and educational partners. We have especially benefited from this approach on the Bryn Celli Ddu project.

As well as identifying best practice, we were interested in identifying challenges in the provision and delivery of public archaeology best practice. Responses included a range of themes, some of which will be specific to Wales, but includes others that are relevant to the delivery of public archaeology in other national and international contexts.

Perhaps especially pertinent to the delivery of public archaeology programmes in Wales, are the nature of communities that may have found themselves excluded from public archaeology programmes. These include intersectional audiences that are deprived and located in rural areas. For these groups, a combination of exclusion from services (including public transport), and a background that does not relate to heritage, may mean people have been historically unlikely to engage with public archaeology programmes. As noted above, consideration of the impact of intersectional identities should be made in public archaeology practice.

Many volunteer archaeologists or groups that engage with public archaeology programmes are highly self-motivated consumers of heritage programmes. Some respondents identified a tension between maintaining this traditional audience, while broadening the reach to non-traditional audiences. Some of the traditional audience may have very specific ideas about 'what archaeology is', and developing understanding in tandem with new technologies and practices may present a challenge in some projects. Seeking to maintain long-term success in engagement, while innovating in delivery media and practices, is key to the fine art of public archaeology. Increasingly, recognising that traditional practices may present barriers to engagement is an important part of public archaeology programme design. Facilitating engagement by enabled members of the public may require consideration in project designs, or be represented by delivery across different media in some projects, or may take the form of widening understanding among members of the public about what archaeology entails.

Continuing consideration needs to be made of the best use of resources in order to facilitate public archaeology practice. Three key issues associated with resources were identified by public archaeology specialists. These were:

Identifying revenue streams will remain a constant issue in the delivery of public archaeology projects. A more specific issue with public archaeology is the delivery of these practices within the developer-led field, where the value of public archaeology projects may be contested in individual cases; equally, large developments with obligations to schemes such as the 'Considerate Constructors' programme maybe especially committed to public engagement. Both issues with identifying revenue streams and delivering public engagement in a 'tender-based' system indicate tensions in terms of what wider culture value is associated with public archaeology. While traditionally public archaeology might have been seen as a 'bolt on', the growing recognition that public archaeology is an essential part of archaeological practice should mean that public engagement is ring-fenced as a central part of tender-based delivery.

Managing success and over subscription for public archaeology projects can be a very real challenge in practice, and one that may occur in surprising or unexpected ways that may have been difficult to anticipate as part of the project design. Arguably, project planning should include mechanisms to document and evaluate success, including over subscription, and analyses of these sources could provide a data-led basis to argue for new income streams. These reviews could comfortably sit within the overall ethical considerations of managing volunteer expectations and managing the end of projects.

Finally, informants identified the importance of undertaking public archaeology research that was directly related to robust research questions, with specific reference to the Wales research frameworks. There may be issues in terms of 'doing public archaeology', or 'doing engagement' as means in themselves, without thinking more robustly about the research context in which projects take place; in every project there should be a balance between methods, outcomes, and engagement.

As a result of these structured interviews, and our own work undertaking public archaeology in Wales (Griffiths et al. 2015a; 2015b; Hijazi et al. 2019), we suggest that there are a series of common themes in best practice. We have differentiated these as the values inherent in public archaeology best practice (Figure 1). We have also identified some themes in mechanisms that could help support public archaeology best practice (Figure 2).

In terms of values, best practices examples are responsive. This includes being responsive to individuals in terms of their health and safety, training, and ethical treatment. It includes ensuring that volunteer archaeologists or members of the public are briefed about what they are doing, how they will do it, why it is important, what it will produce, how these data or evidences or other outputs will be used, what will happen at the end of the project, and what will be the project legacy. This responsiveness includes taking into account the needs or interests and concerns of the group engaged with the public archaeology in terms of project design, delivery, management, and project dissemination and legacy. The best public archaeology projects are also responsive to specific places, environments, or materials with which they work. Specific and nuanced projects, designed to attend to the potentiality of individual case studies, often provide the most elegant solutions, as do projects that respond to the changing conditions of practice over the course of the project's lifecycle.

The second common value that we have identified in best practice in public archaeology projects is the importance of relationships. We suggest that all projects need to develop out of relationships between members of the public, and the inter-agency specialists working on the project, that develop over time. There may not be a formal direct relationship with time-depth of relationships and measures of project successes, but anecdotally, aspects of projects that were identified as successful were produced after lead-in time, or those that used pre-existing or established networks. Projects that were identified as successful used these relationships in co-creative ways; sometimes this could include co-creation in project design or management, or revised aims and approaches as part of the iterative process of project delivery, or in terms of the production of project outputs. In this sense, co-creation is related to project success by also being responsive. By undertaking projects that are people-centred, the most effective projects inculcate a supportive ethos, which emphasises team-working in all aspects. Stimulating and engaging projects are capable of leveraging a wide-ranging network of relationships, including different groups of members of the public, ranges of external specialists including educational professionals, museum professionals, local and national government workers, artists and creatives, university specialists, and many others. While this article has focused on the work of the Trusts, there are a huge range of other participants in delivering public archaeology in Wales. As noted above, this includes the university sector, the museum sector, and the many smaller voluntary societies across Wales. Our own work at Bryn Celli Ddu, has focused on collaboration across these sectors, working with Cadw, the local museum Oriel Môn, Manchester Metropolitan University, Gwynedd Archaeological Trust, the Young Archaeologists Club, the Anglesey Archaeology Association, and external specialists including Dr Alison Sheridan (National Museum Scotland), Prof. Tim Darvill (Bournemouth University), Prof. Mike Parker Pearson (University College London), and Dr Bernie Tiddeman (Aberystwyth University). It has been the focus of UK Research and Innovation funding through both the Arts and Humanities Research Council and Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council.

We suggest that wide-ranging collaborative approaches represent significant potential for public archaeology generally. Specifically, local societies may provide an untapped means to respond to local community concerns and may provide points around which community-led projects could be developed to greatly enhance public archaeology; the kinds of community focus that the 2013 Cadw document identified. The local societies, and the potential 'citizen scientists' these societies include, have been used effectively in previous public archaeology projects in Wales such as HeritageTogether (Griffiths et al. 2015a), and more broadly in digital public archaeology projects such as MicroPasts (Bonacchi et al. 2014) and project ACCORD (Jones et al. 2018). Making use of these existing local society networks to undertake citizen science crowd-sourced work in the historic environment, as part of a research-led project, with national agency support could provide a unique mechanism to respond to the specific historic environment concerns in Wales.

We believe that success can also be promoted by the final value we have identified as important in public archaeology, that of creativity. Ironically, this value can often be overlooked in formal project management and documentation. Fun and playful practices are essential to both the media and messages of public archaeology projects.

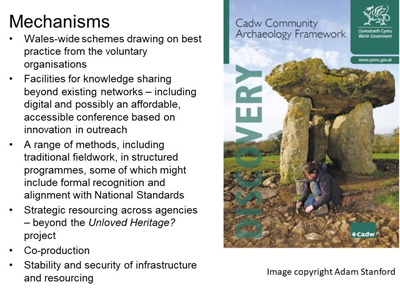

Our research suggests that there are certain mechanisms that should support public archaeology in practice. These could include Wales-wide or other national schemes that draw on best practice from voluntary organisations to provide expertise in public engagement and working with members of the public. In terms of sharing best practice, further facilities for knowledge sharing beyond existing networks, should include digital dissemination, or affordable, accessible knowledge-sharing events to disseminate innovation in outreach. Networked, strategic resourcing for engagement – beyond the Unloved Heritage? project – should develop projects through shared expertise and resourcing. The best examples of public archaeology include a range of methods and traditional fieldwork; in structured programmes, there should therefore be opportunities for sharing schemes or adaptation of existing schemes.

From the point of view of participants, formal recognition of public archaeology programmes or an alignment with National Standards could incentivise public engagement with these programmes.

In order to achieve long-term public archaeology mechanisms, stability and security of infrastructure and resourcing beyond annual funding cycles would be highly desirable. More creative approaches to inter-organisational funding applications – including for example Wales-wide Heritage Lottery Fund applications using the Unloved Heritage? project model – could provide a means to achieve this stability.

Recently, in assessing the heritage sector more widely, Jones and Leech (2015) identified the importance of 'social value' in assessing the importance of assets to a community. Jones (2017, 22) has recently defined 'social value' in the historic environment as '…a collective attachment to place that embodies meanings and values that are important to a community or communities…'. This definition is useful in thinking through concepts of value beyond '…expert-driven…' assessments of significance (Jones 2017, 22). However, in this definition, emphasis still privileges an attachment to specific sites or landscapes, rather than a 'multi-sited' approach to understanding community attachments (cf. Marcus 1995), especially in a digital age (Griffiths et al. 2015a). Further, in terms of public archaeology practice, an emphasis on processes and media, and the distributed network of relationships that create public archaeology, may be as important as the locations of practice. In Byrne's (2008) terms we can think of public archaeology as a form of 'intangible heritage practice', that creates cultural heritage value because of the relationships between a community – whether focused on a locality or forming around a site or network of sites (cf. Harrison 2010, 243).

We argue that best practice is created through such networks of relationships and intangible practices, and especially those that are allowed to develop over time, that emphasise benefits to participants, creativity and participant enjoyment, and that work with a network of partners and organisations. Places where public archaeology is undertaken clearly have value as the nexus of activities, but a recognition of the value of the responsive, creative, relationships that facilitate public archaeology are as important as discourses on the conservation and curation of places in the historic environment. In this context, the importance of the fluid, case-specific and emerging relationships that different people have with the historic environment must be emphasised (Hijazi et al. 2019). In these senses, it may be better to think about locations in the historic environment as significant places in which value is created and understood in the context of a multi-sited approach to practice (Marcus 1995). Indeed, in a digitally distributed, international world, geographical proximity to a particular place may not be the most essential criteria in assessing why people determine places to have social value. We suggest that in public archaeology, the importance of a multi-sited approach (which could include digital work) has been significantly under-estimated. This theme is reflected in our informants' identifications of work such as the Unloved Heritage? and Saving Treasure, Telling Stories projects. These projects actively engage in multi-sited work as part of their creative responses, and have a structure that inherently emphasises multi-agency networks in their approaches. Responsive, creative, relationships to place may include digital work as the ultimate expression of multi-sited public archaeological practice (Griffiths et al. 2015a).

While therefore place-based public archaeology work can act as '…locus for value production and negotiation' (Jones 2017, 32), we would go further. Because the best public archaeology practices creates social value in the historic environment through networks of individuals, communities, and professional and volunteer practitioners, the effective curation of the historic environment requires funding, time and resources to support the inclusive relationships that make public archaeology. Even further, there is the wider political context of the production of other forms of social value in Wales, beyond archaeology. For example, the Wales Government's national strategy of Prosperity for All, which emphasises the social value attached to healthy and active lifestyles. Public archaeology has significant potential to support these themes, both in terms of physical fitness and the effective pathways to good mental health that have been explored in other public archaeology projects (see discussion in Hijazi et al. 2019). Integrating national policy themes of healthy and active lifestyles would provide another means for public archaeology to generate social value beyond an appreciation of the historic environment, and could be productively explored in the future if such projects could be effectively resourced.

Previous documents detailing public engagement in Wales (Cadw 2013) identified key aspects of community archaeology. Our research leads us to a better definition of 'public archaeology' as 'archaeology in the world: negotiated, contested, ethical, and diverse, but work that makes explicit reference to the context of practice'. In surveying the landscape of public archaeology since the publication of the Cadw 2013 Framework, through a series of structured interviews with public archaeologists and our own fieldwork (Hijazi et al. 2019), we have identified strengths, challenges and opportunities for the future delivery of public archaeology. We present a series of case studies in the appendix that detail examples of best practice identified by specialists in public archaeology in the four Welsh Trusts, and our own experience of the Bryn Celli Ddu public archaeology landscape project.

Based on this research, and our experience of working in public archaeology (Griffiths et al. 2015a; 2015b; Hijazi et al. 2019), we suggest that there are consistent values in good public archaeology projects. Good projects are responsive – to individuals; to groups' interests, needs and concerns – and to places, materials and landscapes. Best practice projects privilege relationships that developed over a time-depth; that are co-creative; that are supportive; that are people-centred; and that adapt wide-ranging networks. Central is the importance of creative projects; those that are creative in the media they use; in the messages that are adopted; and in their practices. Importantly, because public archaeology creates social value, effective curation of the historic environment requires support of inclusive public archaeology.

This research was conducted before the current, terrible Coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis. The dreadful death toll will have huge impacts for individuals and communities across the world. The crisis is also having immediate, economic impacts on people working in the historic environment. Professional archaeologists, heritage consultants, and public heritage specialists are being furloughed. Museum and university funding will be more uncertain. The future funding landscape will become much more difficult. In the context of the horrible aftermath of this virus, the future of public engagement with the historic environment may seem trite but, we believe its importance is actually very significant. We have defined public archaeology as 'archaeology in the world: negotiated, contested, ethical, and diverse, but work that makes explicit reference to the context of practice'.

The value of public archaeology, as a form of heritage discourse, is as much about the kinds of societies that we wish to create in the present as it is about seeking to better understand the past. Public engagement with the historic environment reminds us of the enduring qualities of creativity and ingenuity that represent some of the best aspects of humanity from time immemorial. Of course, aspects of the historic environment can also demonstrate some of the worst human traits, including subjugation and violence. As we have noted above, public engagement in the historic environment can directly address well-being and health issues as outlined in the Welsh Government's national strategy of Prosperity for All. But, in times like these, when we face crises and unprecedented uncertainty, the historic environment also matters because it provides us with a connection to human societies across time.

The historic environment represents all of our common human inheritance, and provides us with a connections to human societies that have gone before. It reminds us of the enduring, essential qualities of being human. In this sense, heritage is transcendental.

Public heritage, and the relationships that people make doing it, matter, now as much as ever.

As part of the data collection exercise, the Welsh Trusts were asked to propose a case study in best practice in public archaeology. These demonstrate the importance of responsive, creative projects that privilege the development of relationships with a range of stakeholders in the delivery of public archaeology. They also highlight the diversity of practices, the range of audiences engaged in public archaeology, and especially the importance of playful and fun approaches.

The Unloved Heritage? (unlovedheritage.wales) project is a Cadw-funded undertaking, run by the Trusts in collaboration with the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. The project was conceived and developed by Cadw who sought funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund (then the Heritage Lottery Fund). Following a development year, and a successful funding application, this three-year programme is led by Cadw under the project management of Polly Groom.

The CPAT Community Archaeologist, Dr Penny Foreman, proposed the project as an example of best practice, on behalf of Cadw, the Trusts, and the Royal Commission. Seven projects are being undertaken by the six delivery partners – two by Cadw, one by each of the four archaeological trusts and one by The Royal Commission. The project began in September 2017, and will continue into 2020, with project legacy running beyond. The project is about engaging, enthusing and inspiring young people throughout Wales to get involved with their local heritage. The project aims to provide opportunities for young people to lead heritage interpretation projects on areas of Welsh historic environment that are overlooked, underfunded, under-appreciated and unloved, and includes many different creative and field-based projects. At the programme's core is the innovative approach to the leadership of the different projects; the individual projects are led by the young participants with the partner organisations in a supporting, and not a leading role. This innovative approach directly responds to the core concept of community archaeology as defined in the 2013 Cadw community archaeology framework document, that projects are conceived of and led by the communities themselves.

Unloved Heritage? is exceptionally wide-ranging in the creative media and methods employed, and ambitious in its scope. The project highlights Welsh heritage in innovative ways that appeals to wider, under-represented audiences, and showcases areas of Welsh heritage that have previously been disregarded.

The activities and methods involved have included a wide variety of skills-building sessions, training schemes, and creative outputs. The project emphasises youth-led activities and project design including excavation, unmanned aerial vehicle photography, art installations, and Virtual Reality app design. Because all activities are designed to enable young people to explore the heritage world around them and to tell the stories of their explorations, the project benefits young people by providing empowering experiences and allowing them to become ambassadors for heritage, archaeology, and creative arts. These stories will provide a powerful legacy; a body of increased archaeological and heritage knowledge to interpret local heritage sites.

Unloved Heritage? comprises seven regional projects, delivered by partner heritage organisations across Wales. Each of the seven projects is developed out of consultation, and is responsive to the archaeology and social circumstances of the region. Each project uses creative activities designed to explore the heritage world around young people and to tell the stories of their explorations.

The strengths of the project include that it is entirely youth-led. By engaging young people in the project's 'soft skills' – such as project design and management, and personal development targets – as well as archaeological skills, the project gives young people empowering experiences and allows them to become ambassadors for heritage, archaeology, and creative arts. As a result, the project showcases areas of Welsh heritage that have previously been disregarded in creative and unusual ways. The creative and wide-ranging methods directly contribute to the project's successes; giving young people creative freedom, working with a very broad range of key stakeholders, and thereby accessing sites and resources that were previously 'off limits', the willingness of traditional organisations to employ new methodologies, the inclusion of traditional alongside new approaches, and the inclusion of young people of all backgrounds without prejudice or judgement.

The project was enabled by collaboration across a range of organisations. This was facilitated by the partnerships and close working relationship between the four Welsh Archaeological Trusts. Working nationally, the willingness of Cadw to partner and provide expert assistance and site access was essential to facilitating the project, as was the expertise of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales in facilitating access to archives, training, and the People's Collection.

The DAT case study in best practice, which was proposed by Trust Director Ken Murphy, was the St Patrick's Chapel Excavation (http://www.dyfedarchaeology.org.uk/under projects/Pembrokeshire/St Patrick's Chapel, Whitesands), at Whitesands Bay, Pembrokeshire. The excavation has partners in the University of Sheffield and the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority, and was also facilitated by Cadw grant aid.

The work comprised the excavation in seasons 2014-15 of an early medieval cemetery, which was subject to destruction by coastal erosion exacerbated by climate change. The excavation was accompanied by public engagement on the excavations, and guided tours. Volunteer archaeologists worked with professional archaeologists to excavate almost 100 burials and other important archaeological deposits. The location of the site and the exceptional nature of the archaeology meant that it attracted large numbers of visitors, and guided tours were given throughout the course of the excavation. Reports on the excavation, a film of the 2015 work and other information are available on the Trust's website.

Ninety-one volunteers gave 4210 hours of their time over the three seasons, and 6800 visitors attended guided tours over the three seasons. These guided tours provided one of the main strengths of the project in public archaeology terms. One member of staff (supported by volunteers) was dedicated to providing tours to visitors; without this staffing, undertaking the excavation in such a public place would have been impossible.

The variety of activities associated with this fieldwork meant that enabled visitors could participate using a wide range of skills. The importance of the site, and its role in addressing key research aims, in terms of early medieval Wales, was key to the value lots of visitors placed on the experience. The tangible importance of the site was effectively translated to members of the public and key to members of the public's understanding of the value of the project.

The main strengths of the project were the very high quality of the archaeology, located in a beautiful and well-visited location; the importance of the research was apparent to members of the public. Feedback from members of the public demonstrated this: 'Dyfed Archaeological Trust are to be commended on their talks & access for the public. Our visits here have been a real highlight'. Impacts included tangible changes in people's lives including: that the '…excavation really has broadened my understanding of archaeological recording and excavation techniques…The excavation has…piqued my interest in this period of Welsh archaeology, so much so that I intend to study it at Cardiff University'. The project therefore allowed members of the public to access research outputs, and derive benefits in terms of education, as well as undertaking enjoyable experiences.

The main reason for the project success was having experienced, knowledgeable and dedicated staff who were used to working with volunteers on site, and who were able to deal with and manage the very complex archaeology. The large number of guided tours provided to visitors and local people was one of the main strengths of the project.

However, this success was, at the same time, one of the chief challenges of the project; the unusual and important nature of the site meant that there were large numbers of potential volunteers, and the excavation was over-subscribed. Here, managing success was perhaps the most significant challenge, as volunteer places were over-subscribed, rationing had to be imposed. However, volunteers kept returning as they were enjoying participating on the excavation, making things a little difficult to manage.

The GGAT case study in best practice was the 'Lost Treasure of Swansea Bay', which was one of six projects in different areas of Wales funded by the National Museum of Wales under the umbrella of Saving Treasures, Telling Stories, using Heritage Lottery Fund money. The Lost Treasure of Swansea Bay project was active from September 2016 to April 2017. The project aimed to enable Welsh museums to acquire objects discovered by metal detectorists for their collections, and work with detector groups and local communities to engage with and enjoy the material heritage on their doorstep. Its overall scope was to connect people, objects and places. The Lost Treasures of Swansea Bay was the first of these projects, and was based around a small collection of finds (none classed as treasure trove) retrieved from Swansea Bay by a local metal detectorist. Many of the finds were of Bronze Age date, but the collection also included Roman brooches and medieval pilgrim badges. The project took the form of a number of beachcombing and finds handling sessions. These were initially aimed primarily at local people, but also included visits and participation in one of the walks from a men's community group from an economically disadvantaged area of Merthyr Tydfil, with whom GGAT were working on another public archaeology project with Swansea Museum. Although the main focus was on Swansea Bay, walks were also arranged at Whitford Burrows and Oxwich beach in Gower (which provided analogous sites with physical conditions that would have been similar to the Bronze Age landscape of Swansea Bay). This made the submerged landscape come alive to participants. A visit was also made to Penrhys in the Rhondda, an important pilgrimage centre in the Middle Ages revived by the Catholic church in the 20th century, to put the pilgrim badges in context. Other projects included experimental archaeology workshops making fish-traps, Roman food and clothing, pilgrimages and their archaeology, creating reconstruction illustrations and making replica items, including a Bronze Age spearhead and flint dagger. The emphasis was on engaging with groups who do not normally visit museums or take part in heritage-related activities. The sessions proved the opportunity for members of the public to learn to recognise a wide range of finds. The workshops were designed to put these objects in context: how they were made and used, how they relate to items and activities today, and to impart craft skills.

One of the main strengths of the project was that it was able to benefit from the existing public archaeology network that GGAT had established. This provided the skills base to deliver a wide range of activities, but also provided links between groups that widened the range of communities, including from Communities First areas of economic deprivation, and members of men's and women's community groups from different areas.

The main strengths of the project's legacy were the cross-fertilisation that took place between metal detectorists and the traditional heritage community, forging strong connections between local groups, and the boost to the development of the iThink humanities unit of the new school curriculum, subsequently developed between the partners and Olchfa School in Swansea.

The forms by which the project was delivered were key to its success; it included lots of practical activities and site visits. The finds were also very evocative: Bronze Age weapons from the submerged landscape in Swansea Bay, Roman jewellery and medieval pilgrim badges. The stories they generated were therefore particularly engaging.

The project took place in an uncertain funding environment and at the same time as restructuring in the museum, all of which presented challenges to the project delivery. The support from Cadw for Regional Outreach allowed the development of long-term relationships and was essential for negotiating this funding uncertainty, and providing project legacy.

Dan Amore, Community Archaeologist at GAT, detailed an example of best practice in public archaeology in the Tŷ Mawr Hut Circles, Holyhead project with Ysgol Cybi. The project took place over two days in August 2018 and included a series of visits to the Iron Age site as part of the school's Celts project, undertaken by years three and four. The visits involved an introduction to archaeology, and a walkover survey; each pupil was to 'be an archaeologist' for their session. These activities developed navigation skills, and participation in archaeological recording techniques and fieldwork. The project supported the pupil's Celts theme by introducing pupils to an archaeological site and situating it in the wider historic environment. This included creating experiential-rich understandings of the past, exploring what life might have been like when the site was in use.

One hundred and fifteen year 3 and 4 Ysgol Cybi pupils were included in the educational sessions. GAT designed sessions for each class (20–25 pupils each), and the content and timetable were agreed with the head teacher prior to delivery. Before the school visits, GAT staff visited the site as part of the planning process for the sessions, and also conducted a risk assessment. PowerPoint presentations, a kit list and timetable were distributed to the school teaching staff prior to the site-visits. These days comprised a two-hour session on site per class. Each class was divided into five groups, with a member of GAT or school staff leading each group.

One of the major strengths of the project was the 'hands on' learning it provided. There was an 'excitement factor' in the project; this resulted from a trip, outdoor learning, and use of specialist 'grown up' equipment (including tape measures, clipboards, digital SLR cameras, ranging poles, and photo scales). The immersive learning environment helped the children understand their Celts project and the site in the wider historic environment context. It provided a breadth of activities that engaged pupils for the whole session. The outdoor exercise exploring the roundhouses provided an especially fun series of experiences. By teaching the pupils in age-cohorts the learning experience was tailored to the students' needs.

One of the keys to the project's success was the degree of planning with the school; this and the pre-site visit ensured that the event ran smoothly. The combined expertise of the school and GAT staff were essential; the GAT team were experienced in working with this age group, which meant that they could convey ideas, and produce study aids at the correct level of complexity. By undertaking class activities, and smaller group activities there was a sense of dynamism in the learning environment. At the site, each group could record their own hut circle, and this gave the children a sense of engagement and ownership of their learning.

The challenges in this ambitious project derived from working with large numbers of children outdoors. The weather on the delivery days was very hot, and ensuring the safety of the children was paramount. The sessions were very tiring for the staff involved, and required considerable investment of resources in terms of preparation time, resources and logistics.

This creative project was enabled by a close working relationship between staff in GAT and the school. The school afforded the GAT outreach team considerable freedom in planning the project. This was of direct benefit to the project, allowing experienced professional heritage educators creative freedom in project planning. The opportunity to align the school project with a specific, local archaeological site, and undertake the learning outdoors, using specialist archaeological equipment, and with professional archaeologists, provided a unique immersive experience. The Gwynedd Archaeological Trust Historic Environment Record was invaluable for the Outreach Team researching the experience.

Since 2015, the Bryn Celli Ddu passage tomb on Anglesey has become the centre of a public archaeology landscape project, a partnership between Cadw, the historic environment service for the Welsh Government and Manchester Metropolitan University. The project focuses on the surrounding landscape around the main monument of Bryn Celli Ddu passage tomb, following its excavation by archaeologists in the 1920s. Bryn Celli Ddu is a monument of international importance; it is one of only a few passage tombs in Wales, and demonstrates links to practices in Orkney and elsewhere in Europe, in Ireland, France and Portugal. However, despite this international importance, the monument was not as widely known or robustly understood as it deserved. Our reason for wanting to carry out the project is to raise awareness of Bryn Celli Ddu in order to better manage and protect the site through greater community involvement. The project runs in June and July each year, and aims to work with local audiences (targeting local residents from north-west Wales), local schools, the local Young Archaeologist Club and university students, to carry out a variety of site and community-based activities including an excavation, lectures, museum exhibitions, open day events, public and schools outreach. The project has grown in recent years to include a 'Festival of Archaeology' working with stakeholders from across the region, and international visiting specialists (for example delivering the public lecture series). The project has included research into the innovative use of digital technology for public engagement funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, and artists in residences.

Visitor numbers at the open day were 716 in 2016, 700 in 2017, 650 in 2018, and in 2019 a total of 1993 visitors came to Bryn Celli Ddu, making this a standout event at a rural unstaffed Cadw monument. In 2019, the education programme included visits from seven local primary schools totalling 182 primary school children, c. 20 Young Archaeology Club participants, and 10 local volunteers. The school outreach programme was tailored to fit the particular learning needs and interests of the school group. Six out of seven schools were Welsh language schools and these visits were conducted in Welsh. A prehistoric handling collection and a number of art activities were developed through discussion with teachers (designed for Key Stage II). Session activities ranged from short talks, storytelling, art activities, handling of replica artefacts, pottery workshops and question and answer sessions. All school groups were also taken on a tour of the monument and the excavation. In 2018 and 2019, the project worked with Oriel Môn to co-produce exhibitions and a public lecture series from international specialists. In 2019, 133 people attended an at-capacity lecture by Professor Mike Parker Pearson, University College London, on 'Stonehenge and Wales'. Members of the project team led three archaeological group walks around the site and landscape as part of a programme of walks. Other events include a stargazing, a sun-rise event, local society talks throughout the year, and a treasure trail. The 2019 press release was really well received among broadcast, online and print media and was shared across 25 platforms, with some publications sharing the story multiple times. This amounted to a huge coverage with 6.96 million 'opportunities to see'.

The strengths of this project derive from its cross-institution network. Working between the national and local government sector, the university sector, the museum sector, and in combination with heritage organisations including Gwynedd Archaeological Trust and the Young Archaeologists, means that this project benefits from the support of wide-ranging expertise and sources.

The successes are indicated by positive feedback from members of the public (see for example Reynolds 2019), and the ability of the project to undertake public archaeology that addresses important research and curatorial objectives.

We would like to thank all of the Welsh Archaeological Trusts (Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust (CPAT), Dyfed Archaeological Trust (DAT), Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust (GGAT), and Gwynedd Archaeological Trust (GAT), but especially Andrew Davidson, Dan Amor, Dr Edith Evans, Ken Murphy, Paul Belford, and Dr Penny Foreman. We would also like to acknowledge the help in our public archaeology work of Gwilym Hughes, and Ian Halfpenny at Cadw; Matt Venables, the Marques of Anglesey, Trefor Lloyd; Kris Hughes and all at the Anglesey Druid Order/Urdd Derwyddon Môn; Dr Tosh Warwick and Helen Darby at Manchester Metropolitan University; Ian Jones and all at Oriel Môn; Jon Swogger; Prof. Jonathon Roberts, Dr Bernie Tidderman, Dr Helen Miles and all on the HeritageTogether project; Prof. Mike Parker Pearson, Dr Alison Sheridan, Dr Kenny Brophy, Prof. Tim Darvill and Dr Steve Burrow; all our volunteers and students over the years; and, most importantly, all the members of the public who have worked with us. This research was made possible by support from Manchester Metropolitan University by the AHRC-funded 'HeritageTogether' project and the AHRC-funded 'Experiencing the Lost and Invisible' project.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.