Cite this as: Ilves, K. and Marila, M. 2021 Finnish Maritime Archaeology through its Publications, Internet Archaeology 56. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.56.17

In Finland, 1963 was a landmark year for maritime archaeology. With the implementation of the Antiquities Act, all ships that had sunk more than 100 years ago were brought under legal protection for the first time in the history of Finnish heritage management. The implementation of the act marked the beginning of a gradual increase in the number of maritime archaeological research projects – a phenomenon characteristic of the whole Baltic Sea area since the early 1960s (Cederlund 1983; 1995; Mäss 1991; Schlichtherle and Kramer 1996; Barstad 2002; Ilves 2008; Pydyn 2008; Weski 2008; Pranckėnaitė 2010; Bass 2011).

With over half a century of established, executed, and legally defined practice in Finland (see Marila and Ilves 2021), we set out to analyse Finnish maritime archaeology through its publications in order to gain a critical insight into the trends in maritime archaeological research in the country. This is the first systematic study of research trends within Finnish maritime archaeology. The analysis is based on a bibliography of more than 600 works focusing on the country's maritime archaeology in the widest sense. The bibliography compiled (Table 1) is the first of its kind, too, as no such listing has existed until now.

Between the early 1960s and the mid-1990s, general bibliographies of Finnish maritime literature were published (Finnish Maritime Literature 1963–1996). However, although the six volumes in the series included both original and translated literature published in Finland and on a wide range of maritime topics, only the first four volumes listed maritime archaeological literature and, owing to narrow thematic and disciplinary definitions, to a limited extent. Similarly, general bibliographies have been compiled for all archaeological literature published in Finland. The first Finnish archaeological bibliography was published by A.M. Tallgren (1916) and lists 1700 works produced prior to 1914. Understandably, there is no maritime archaeological literature to be found in this bibliography. To our knowledge, the most recent archaeological bibliography was compiled by Ella Kivikoski (1983) and lists about 1000 works published between 1971–1980, including some maritime archaeological literature.

As the first extensive maritime archaeological bibliography, ours cannot be seen as perfect and complete either. While compiling the bibliography, we were in many cases basing our assessment on the titles of the publications. In such cases, we cannot be entirely certain about the contents of the work and, obviously, publications with titles not referring to anything maritime archaeological may have escaped our study. Furthermore, due to the COVID-19 outbreak, several potentially relevant publications remained inaccessible and unavailable during this study. Therefore, the compiled bibliography is not exhaustive for the years covered, and should be considered more as a starting point for subsequent work. Nevertheless, thanks to the large amount of data obtained, the list is certainly enough to catch the general trends, providing a reasonable representation of the discipline in Finland.

This is to say that every bibliography produced has its own conceptual approach. We aimed for diversity, but also comprehensive coverage. This approach enables us to explore the development of Finnish maritime archaeology in terms of its focus and content, both in academic and public arenas, nationally as well as internationally. One of the main aims of our study is to evaluate the scientific activities and pinpoint the strengths and weaknesses of the knowledge production processes in the field of maritime archaeology in Finland. Our bibliography serves as a tool for determining the status of research, as well as possible gaps in knowledge, and it has potential to become important for the development of new research fields. Below, we first describe the methodology of compilation. Discerned patterns are then explored, and a summary of statistics presented. Our findings are thereafter analysed through a discussion on the general development of the field, on research concentrations and available research material, and on the development of higher education in maritime archaeology in Finland.

Hundreds of thousands of articles are published annually around the world, as the publication of research, regardless of the field or discipline, is an expectation if not direct requirement in the sciences and the humanities. Today, the prospect of compiling a worldwide bibliography of even small disciplines such as maritime archaeology would be impossible. In addition to the sheer amount of published literature, another challenge concerns the definition of maritime archaeology. Although the field can hardly be seen as new (Catsambis et al. 2011), it is still defining itself (Bass 2011, 4). We define maritime archaeology in the widest sense as archaeology that aims to understand humankind and its history with the help of material and non-material remains connected to water. Thereby our definition suggests that maritime archaeology is more than submerged sites and nautical source material, which we nevertheless acknowledge as the main pillars of the discipline. Our encompassing definition of maritime archaeology is also reflected by the bibliography, and entailed various demarcation challenges in the compilation. For instance, drawing a line between maritime archaeological and maritime historical work can be arbitrary. We have excluded publications that are clearly maritime ethnological, as well as works that deal with recent maritime history. At the same time, we included maritime historical publications that draw from maritime archaeological source material. Similarly, it is difficult to say whether a publication about coastal Stone Age people's relationships with land and sea is maritime archaeological or not. Anything that deals with the outcomes of shore displacement processes could quickly turn into maritime archaeology. Thus, we have included research on maritime cultures, archipelagos, and coastal areas if they appeared to contextualise themselves as part of maritime archaeological research traditions and, for instance, reference the concept of maritime cultural landscape (Westerdahl 1992). This also means that we see the process of maritime archaeological knowledge production as a historically and geographically specific and definable communal practice, and that the evaluation of the process hinges on an understanding of when, where, by whom, and for what purposes that knowledge was produced (e.g. Roberts et al. 2020).

In compiling the bibliography, we first issued a call for lists of publications to the Finnish maritime archaeological community by personally contacting researchers and professionals in archaeology and heritage management. We also reached out to amateur archaeologists and hobby divers through the Finnish Maritime Archaeological Society. Parallel to this, and in addition to internet searches on Google Scholar, searches for references were done on available national reference databases, such as the University of Helsinki library database Helka, and the National Library of Finland metadata resources Melinda and Juuli. In those databases, as well as on the internet, we searched for a host of relevant terms in Finnish, Swedish and English, starting with the different forms and combinations of the terms 'Finnish', 'archaeology', 'maritime archaeology', 'wreck' and 'underwater'. We also searched the databases using the names of relevant maritime archaeological publication series as well as the names of Finnish maritime archaeologists and known sites. In addition to internet, publication, and reference database searches, general archaeological periodicals and series, such as those published by the Finnish Archaeological Society, were browsed for maritime archaeological articles either by accessing digitised collections or physically in libraries, such as those at the University of Helsinki and the Finnish Heritage Agency (hereafter FHA). We also searched international publications such as conference proceedings, monographs, and journals for research by Finnish and non-Finnish maritime archaeologists dealing with Finnish material. Furthermore, to a certain extent, lists of references in published maritime archaeological research were manually checked to identify further works.

We included in the bibliography scientific publications, such as monographs, journal articles, book chapters, report series and theses with a clearly communicated maritime archaeological focus and research material located in Finland. In contrast to many other overarching studies in Finland, we also included research on the Åland Islands, an autonomous, monolingually Swedish-speaking part of Finland where Finnish, Swedish, and Sami are official languages. Publications by Finnish maritime archaeologists dealing with materials outside Finland were not included in the bibliography, while publications on Finnish sites and materials published by non-Finnish researchers were included. In many cases, English or Swedish translations were available for works originally published in Finnish. If the same work was published in two or more languages, generally only the Finnish version was included, although there are exceptions to this rule if the same work was published in different venues. In some cases, where Finnish material makes up a part of the research material or area, we have also included research that covers large collections of materials or geographic areas outside Finland. In these cases, research by Finnish and non-Finnish researchers alike was included.

We also included popular scientific monographs and articles, but excluded biographies, interviews, book reviews, museum exhibition reviews, newspaper stories, conference abstracts and reports. Historiographical research on the history of maritime archaeology and the related field of underwater cultural heritage management, including contributions by or reporting those of hobby divers, have been included to the greatest possible degree. One important excluded body of material relates to unpublished archaeological fieldwork reports, mainly from surveys done for the purposes of heritage management and protection. The majority of reports on fieldwork done in mainland Finland have recently been made available electronically at https://www.kyppi.fi by the FHA, while recent reports on investigations done on Åland remain undigitised. We also excluded non-archaeological and non-heritological publications dealing purely with legislative issues, even if related to wrecks, but included publications related to the legislation, management and protection of underwater cultural heritage in general. We excluded non-scientific and sporadic internet publications such as blog entries, as well as electronic audio and video recording publications. Similarly, although in recent years an important channel for public outreach, we did not include writings on social media.

Due to the relatively recent professionalisation and small scale of maritime archaeology in Finland, the definition of Finnish research material or research area is rather unproblematic. The geographical borders of Finland have stayed the same since the late 1940s, and even if most sunken ships found in Finnish waters were not originally Finnish, under the Antiquities Act, they belong to the state. In this respect, it is relevant to note that the autonomous Åland Islands have their own antiquities law and the Åland Parliament has the right to pass legislation on cultural heritage. However, also on Åland, all ships that sunk more than 100 years ago, as well as other underwater remains, are legally protected. Also worthy of reflection is the number of people active in the field of maritime archaeology in Finland, which has remained practically unchanged since the late 1960s when the professionalisation of the discipline begins (Marila and Ilves 2021, 334).

The compiled bibliography of Finnish maritime archaeology includes 621 works in total, written in Finnish, Swedish, English, and German (Table 1). The first publication in our bibliography dates to 1942 and the last year and the end date of inclusion is 2020.

Complete bibliography of 621 scientific and popular works in Finnish maritime archaeology published between 1942–2020. [Download as XLSX | CSV]

The references were categorised according to their publication character as international, national, local, and grey literature. Local publications were defined as publications mainly circulated in the local areas, and grey literature in terms of availability and the special effort that must be made to trace and acquire such material. For instance, we treated all bachelor's and master's theses as grey literature. Based on titles and content, the references were further classified into thematic categories as archaeological, historical, heritage management, popular scientific, and other. The latter category comprises a variety of topics, but mainly falls within the field of scientific methods and techniques applied to maritime archaeological materials and/or environments, and to a lesser extent, historiographical research.

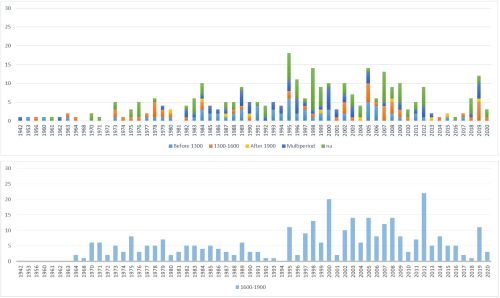

To facilitate the analysis, the references were grouped into six categories according to their chronological concentration: (1) before 1300, (2) the 14th–16th centuries, (3) the 17th–19th centuries, (4) 1900 onwards, (5) covering three or more of the previously mentioned categories of time, and (6) chronological determination not applicable. Where the subject matter of the work related to two different periods of time, we coded the reference following the oldest of the covered periods. For example, a research article dealing with the Finnish archipelago coast as a zone of interaction from prehistoric to high medieval periods was placed in category (1). With all the references, it was also clarified if the work deals with underwater source material or not, as well as if the research concerns shipwrecks or not. As a special case study into how much attention wrecks have attracted in publications, we listed all works dealing with the wreck of the 18th-century Dutch merchantman Vrouw Maria, archaeologically one of the most significant ship findings in Finland.

The categorisation and classification of the titles included in the bibliography were subjected to reliability checks and the full contents of approximately half of the works in our list were consulted by accessing the publications directly, including all publications whose subject matter was impossible to infer reliably from the title or publication avenue alone.

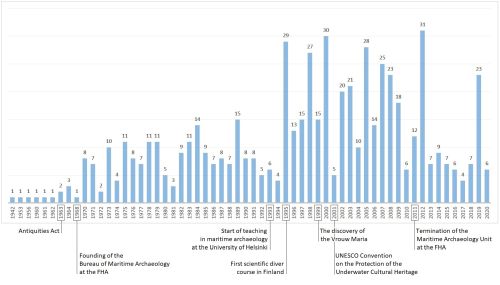

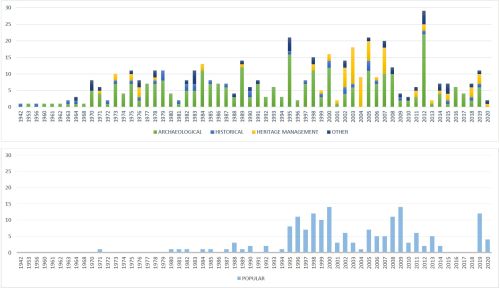

Although the first publication in our bibliography dates to 1942, and publishing in maritime archaeological themes is thereby, sporadically and on a small scale, initiated in Finland, publication of research only became annually consistent from the 1970s (Figure 1). However, publishing does not show an increasing trend that we were expecting to see from this point. The 50-year-long period from 1970 to 2020 displays clear variation in publication numbers, and three periods of different publication intensity are evident within this timeframe. There are 198 references from the 25-year-long period of 1970–1994 with a median of 8 works per year. Over half of the references in our bibliography, 342, belong to the 18-year-long period of 1995–2012. During these years research intensity was high in Finnish maritime archaeology with a median of 19 works released annually. The last period, covering the years 2013–2020, exhibits a marked decline in the number of available references. There are in total 69 works from this period available and the median lies at seven works a year (Figure 1).

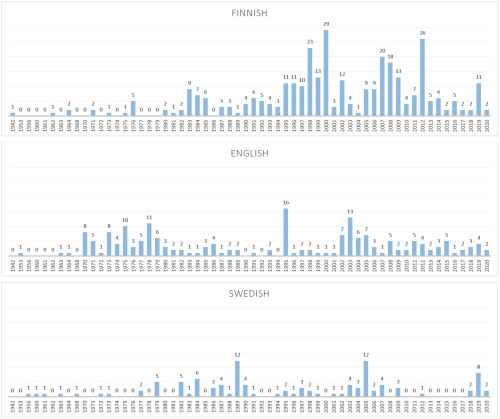

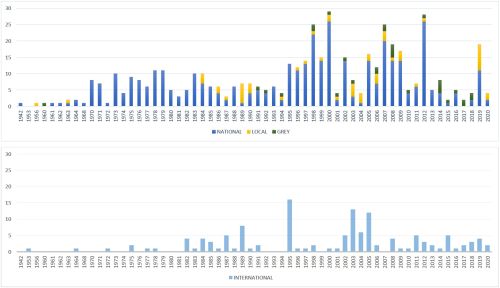

Of the 621 references in our bibliography, 327 are in Finnish, 189 in English, 104 in Swedish and one in German (Figure 2). Accordingly, almost 70% of the references represent works available in the national languages of Finland and 30% facilitate international accessibility. However, when it comes to defining the target audience of the publications vis-a-vis their language, we have not routinely defined all publications written in or translated into English as international publications because the matter is also connected to the choice of publication venue. When it comes to the place of publication (Figure 3), only 131 references can be regarded as published internationally and as many as 402 references are classified as targeted on a national audience; 58 references have been published locally, and 30 are counted as grey literature, consisting mainly of student papers. Thus, only 21% of the references in our bibliography of Finnish maritime archaeology are readily available for international audiences.

While the national and local publications taken as a whole follow the observed pattern of the publication intensity, international titles, both in terms of language and venue, do not exhibit any trend in relation to the timeline of the publications. There is, however, a notable amount of work in English published in the 1970s that is connected to the chosen language of an annual report series published by the Bureau of Maritime Archaeology (see below). While there is a small increase in the number of international publications starting from 1995, in the wider context this is close to negligible as the median increases from one international publication a year during 1970–1994 to two during the periods covering 1995–2012 and 2013–2020.

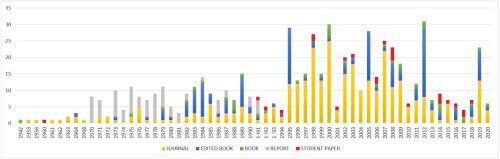

There are 331 references tied to journals, and an additional 151 works are published as contributions in edited books. In the bibliography, there are also 38 works classified as monographs, including booklets, over one-third of which are co-authored. All 76 references categorised as reports are connected to the annual report series published by the Bureau of Maritime Archaeology. In addition, there are 25 student papers, i.e., bachelor's and master's theses, which are equally distributed between the universities of Helsinki and Turku, where maritime archaeology has been taught sporadically since the 1990s (Marila and Ilves 2021, 341). As over half of the references are journal publications, it is not surprising that this type of publication correlates with the observed temporal pattern of publication intensity. Report-type references, however, are restricted to the first of our defined period of publication: years 1970–1994. Except for one master's thesis about boat graves in Finland written at the beginning of the 1960s (Andersson 1960), student papers started to appear more regularly in the 1990s, but remaining low in numbers. There is no discernible pattern regarding books and book chapters, though a slight statistical increase in the number of contributions to edited books can be traced after 1995 (Figure 4).

Our bibliography has a pronounced focus on maritime archaeology. Consequently, many of the references in it, 295 works, are thematically and primarily categorised as 'archaeological' and concern research works as opposed to maritime archaeological works with a popular scientific character. The latter category is, however, represented with 167 references. In addition, there are 74 references representing research related to heritage management in the sphere of maritime archaeology, and 38 works are labelled as 'historical' research. Forty-seven references were classified as 'other' without any further distinction on a finer scale. Thus, in broader terms, 454 references could be termed 'scientific' and 167 'popular scientific' (Figure 5). There is a very distinct rise in the number of 'popular' works from 1995 onward, occasionally even outnumbering the total body of work identified as research. There is, however, also a clear break in popular scientific publications during 2015–2018; at the same time, the year 2019 appears as particularly active, mainly due to the publication of thematic issues of popular scientific magazines. Another remarkable aspect is the number of references connected to underwater and maritime heritage management. Over two-thirds of the references representing this type of work in our bibliography belong to the period 1995–2012, in particular the years 2002–2007, when each year saw a median of seven heritage management-related papers.

For the main aim of our study, the temporal classification of the research focus as evident from the publications was carefully designed. There are 67 references pointing towards research focusing on prehistoric and early medieval times (before 1300), 56 relate to study of the 14th–16th centuries, 321 works concern the 17th–19th centuries, 10 references in the bibliography focus on the period after 1900, and 62 references indicate a multi-period approach. In addition, 101 references did not allow for a chronological classification. Many of these works are related to the technological and methodological advancements in maritime archaeology or to legislative and historiographical developments of the field. Based on these data, the prevalence of research focusing on the 17th–19th centuries within Finnish maritime archaeology is undeniable. Even if the sum total of all other references allowing chronological definition (195) are compared to the amount of research related to the 17th–19th centuries, the dominance of the latter is hardly counter-balanced by the other time periods (Figure 6).

Although the compilation of the bibliography followed an encompassing definition of maritime archaeology, 479 references, 77% of all works within Finnish maritime archaeology available for this study deal with underwater source material. Furthermore, the staggering majority, 421 of these works, focus on shipwrecks, whereas 277 are concerned with shipwrecks from the 17th–19th centuries. Moreover, in our study, special attention was directed to identifying publications on the wreck of the Vrouw Maria, the well-preserved remains of the 18th-century Dutch merchant ship discovered in 1999. One hundred and seven works deal with this shipwreck or material from it, meaning that 17% of the references in the whole bibliography are connected to Vrouw Maria in one way or another (see also below).

Interestingly, of the 142 references that do not focus on the underwater source material, only 41 were written in Finnish, while 43 are in English and 58 in Swedish. The corresponding numbers for underwater archaeology are 286 in Finnish, 146 in English and 46 in Swedish. Thus, while research published in Swedish deals equally with maritime archaeology both underwater and above, research published in Finnish is heavily focused on underwater source material, as is the research in English (87% and 77% focus on underwater archaeology, respectively).

In this context, the question of concentration in popular works is relevant since they make up 27% of all references in our bibliography. Of the 167 popular works, 152 (91%) deal with underwater material and, of these, 144 deal with shipwrecks. Of all popular publications, 43 (25%) are in one way or another about the Vrouw Maria, most likely because of its reputation as a treasure ship and the legal aspects raised by its discovery. Of the 15 popular works that do not deal with underwater material, only three are written in Finnish and all other works are in Swedish.

Publishing of maritime archaeological literature in Finland started in the early 1940s. Not surprisingly, during the first decades, until the late 1960s, maritime archaeological research and publication was sporadic and sparse. Early publications can be characterised as brief introductory overviews on an emerging discipline and much of the activities on, for example, underwater sites and wrecks, if reported to the FHA in the first place, were rarely published and therefore remained unrecognised by the wider scientific community. Early published works in maritime archaeology focused rather on terrestrial source material and chronologically on prehistoric and medieval periods.

The year 1970 forms a clear turning point in the amount of published works in maritime archaeology. This is related to the establishment of the Bureau of Maritime Archaeology (Bureau of Maritime History between 1972–2004) by the FHA in 1968, a section of the organisation dedicated to the management and research of underwater and maritime heritage. The early research conducted by the bureau was published between 1969–1975 in their own series, The Bureau of Maritime Archaeology/History Report, and subsequent research, now also including contributions by researchers beyond the bureau, in The Maritime Museum Helsinki/Finland Annual Report series (until 1991) and the Nautica Fennica series (since 1976). Interestingly, the bureau published its early research in their report series in English (and later in Finnish with English translations), possibly to cater for international audiences, although the range of readers reached outside Finland through this avenue remains unknown. Knowing whether and to what extent the annual reports or the Nautica Fennica series, or other similar publications in English, have been referenced in international publications would require a citation analysis, which falls outside the scope of this study.

The 1980s mark a more tangible beginning of internationalisation in Finnish maritime archaeology. For instance, the Bottnisk kontakt conference proceedings began to be published in 1982 (Westerdahl 1982), and the series became a forum for maritime historical, maritime ethnological, and maritime archaeological research done on both the Finnish and the Swedish side of the Gulf of Bothnia, occasionally also including research from the eastern side of the Baltic Sea as well as the very north of Fennoscandia. The publication of Bottnisk kontakt reflects a larger change that took place during the 1980s. Whereas much of the research done in the 1970s were published in the bureau annual reports and Nautica Fennica, the 1980s demonstrate an increase in articles published in edited volumes such as conference proceedings and general guidebooks to underwater research.

This is a good moment to reflect on the impact of internationalisation on the discipline itself and on the perceived quality of research. Although we place the beginning of international publishing in the early 1980s, there is no noticeable increase in the amount of works published in English. We do, however, witness an increase in the number of publications in Finnish. Similarly, the number of publications in edited books and journals correlates positively with our identified period of internationalisation. However, the small number of publications in English, coupled with the increase in the number of publications in Finnish, leads us to question the premise that publishing in English in international peer-reviewed top journals would automatically lead to more relevant and higher quality research (see also Lang 2000).

Any form of discourse analysis falls outside the scope of this article, but it is safe to say that the writing style in much of Finnish archaeology has been distinctively descriptive and therefore aimed at a distancing of the researcher from the epistemological problematics concerning knowledge production (Marila 2018; Lucas 2019). Descriptive accounts of research material often find their audience from within the national rather than the international arena, and their epistemological merits should be weighed against the knowledge needs of the local scientific community in question (Sturt 2008). On a related note, much of the published scientific research in Finnish maritime archaeology has been carried out by FHA personnel whose main responsibilities are in heritage management rather than scientific publishing. Compared to non-refereed publications, the time cost of peer-reviewed journals is considerably higher, and when publishing is not important for career development or institution funding, as is the case with the FHA, authors opt for less time-consuming publication avenues.

Another aspect to keep in mind is the authors' gender. Contrary to how maritime and underwater archaeology in particular is often seen as dominantly androcentric (Flatman 2003; Ransley 2005), the opposite is the case in Finland: for decades, the development of scientific maritime archaeology in Finland has rested on research and publishing by women. However, while women are active in unrefereed publications they remain underrepresented in peer-reviewed journals internationally (Fulkerson and Tushingham 2019; for an intersectional take on the issue, see Heath-Stout 2020). Although not specifically researched, this may well also be the case in Finland (see also Immonen et al. 2010), as during the past decades the overwhelming amount of Finnish maritime archaeologists have been women, and women are less likely to publish in refereed journals than men.

Drawing from the idea that research is a communal practice with historically, socially, and regionally specific knowledge production objectives, and keeping in mind the close ties between Finnish maritime archaeological research, heritage management thereof, the important role of the avocational sector, and the extremely small amount of research coming out of academia, the low number of publications in international forums is hardly surprising. For instance, we are not aware of the exact motivations behind changing the language of the bureau's Annual Reports from English to Finnish in the first place, but it may reflect the normalisation of the avocational sector as an important part of the knowledge-producing community and therefore the target audience of publications (see also Bell 2018).

The inclusion of the avocational sector is also reflected in the thematic shift that happened during the 1970s–1980s. Compared to the 1960s, we see an increase in the number of publications dealing more specifically with individual sites and types of materials. For instance, the wreck of the St Nikolai, a Russian frigate that sank in 1790 close to the present-day city of Kotka in south-eastern Finland, was particularly central. Early research on St Nikolai, and other sites like it, were important for the development of the wider research community, consisting of researchers, heritage officials, and avocational archaeologists, and therefore pertains to the nature of knowledge production in Finnish maritime archaeology more specifically. Although too often credited as little more than looting, the input of hobby divers has always been central to knowledge production in maritime archaeology around the world, especially during the early decades of the discipline's development (Goggin 1960; Watts and Bright 1973; Flatman 2007; Tuddenham 2012; Galili et al. 2018). In Finland, collaboration between avocational divers and heritage officials began on the St Nikolai and continues today in the form of research carried out on other important wrecks (Marila and Ilves 2021, 343). In other words, the local avocational sector is one of the largest audiences for maritime archaeological research and, while large-scale international projects have been carried out in Finnish maritime archaeology, knowledge production within the authorised heritage discourse (Smith 2006) has aimed to fulfil the needs of local and national rather than international audiences.

The amount of published works grew in the mid-1990s, and the reasons behind this are also connected to the close ties between the heritage management/scientific community and the public audience. There is a clear thematic diversification in articles published in the Nautica Fennica series, and conference proceedings reflect a similar increase in the number of publications and topics addressed. More important for the increase in the number of publications, however, was the appearance of the popular magazine Sukeltajan maailma (Diver's world) in 1995. Popular scientific publications cover a wide range of topics from technological innovations to legal issues, but the prevalence of wreck-related articles and books is undeniable. Important in this respect was the discovery of the Vrouw Maria in 1999, leading to successful funding for continued research. The discovery also created a lot of public attention, not least due to the legal cases concerning the ownership of its precious cargo. Underwater research on the site began in 2000 and continued until 2010. Within that period, the research was published in English in the newsletter of the international research project MoSS (Monitoring, Safeguarding and Visualizing North-European Shipwreck Sites) in 2002–2005. The project was important for Finnish underwater heritage management mainly because the research was carried out by the FHA, but also because the discovery of the Vrouw Maria initiated a long legal process during which the Finnish Antiquity Act was put to the test and ultimately updated as a result (Alvik and Matikka 2011).

The Vrouw Maria is important when reflecting on the high prevalence of heritage management related publications in the 2000s. Of these publications, the MoSS newsletters make up one half. Equally important for the great amount of underwater heritage management publications must have been the UNESCO 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage that sparked discussions on the possible effects of its ratification (e.g. Fast 2002); the convention remains unratified in Finland owing to the legislative strength of the Antiquities Act. Even if the Vrouw Maria is an important part of Finnish heritage management, research on the site has produced and continues to yield a lot of maritime archaeological publications, too. Almost one-fifth of all publications in our list are related to the Vrouw Maria, either through archival research on the possible location of the wreck up until its discovery, to its protection, or the archaeological research conducted on it. The year 2012 appears as particularly active in terms of the amount of published works, which is mainly due to the publication of a collection of articles (see Figs 1 and 4) most of which deal with the Vrouw Maria (Ehanti et al. 2012).

The research generated by the discovery of the Vrouw Maria reflects a general trend in Finnish research. The large number of well-preserved wrecks of wooden ships from the historical period in the coastal waters of Finland also means that research has concentrated on those. The Vrouw Maria, although the single most dominating topic in all the research, is of course only one ship, but one can identify other similarly formative discoveries in the history of Finnish maritime archaeology, starting with the St Nikolai. We have elsewhere provided a historical overview of Finnish underwater archaeology in light of the research carried out on important wrecks and will not repeat it here (Marila and Ilves 2021). Nevertheless, what our analysis of published works highlights is an unwavering and uninterrupted research interest in underwater nautical archaeology belonging to the historical period.

There are clear reasons for this concentration. Of the more than 56,000 (as of 17 March 2021) sites listed in the FHA registry of protected cultural heritage sites, 2233 are located underwater. Most of these are shipwrecks (1682), especially from the historical period (1114). There are only 11 underwater sites from the medieval period, eight of which are wrecks. Just 29 underwater sites dated to the prehistoric period are listed in the registry, none of which are wrecks. The small number of underwater sites other than wrecks is also reflected in publications. Of the total of 621 references in our bibliography, 480 (77%) are underwater-orientated, while within that category 421 works (88%) deal specifically with wrecks underwater. A further 25 publications deal with wrecks found on dry land and are therefore not identified as underwater-orientated in our classification. Naturally, not all the remaining publications deal with particular sites or materials, but it is still worth reflecting on whether the amount and thematic focus of publications match the overall nature of all known heritage sites listed by the FHA, and in so doing highlight possible gaps in the existing research.

Estimating whether the relative amount between research on wrecks underwater and all other maritime archaeological research matches the situation with all known sites is a matter of how one defines maritime archaeology and, thereafter, how one estimates the total number of listed sites with maritime archaeological research potential. Firstly, insofar as it is safe to say that all underwater sites listed in the FHA registry are maritime archaeological sites and materials by definition, we notice that the proportion of publications dealing with wrecks underwater (88%) is higher than the proportion of wrecks among all underwater sites listed in the FHA registry (75%). We interpret this to reflect the fact that wreck-related knowledge is considered important, not least because of the central role of the heritage management sector and hobbyists in the production of knowledge related to these sites. We also feel that the type of sites listed in the FHA registry as underwater sites other than wrecks (551), many of which are constructions of various kinds – palisades, remains of harbours, etc. – are to some extent represented in the c. 60 publications listed in our bibliography as underwater but non-wreck-related. However, when considering that this category includes methodological guides and publications about diving in general, the number of publications that address non-wreck-related underwater sites and materials (10%) is not in line with the amount of registered underwater heritage sites that are not shipwrecks (25%).

Secondly, and in keeping with our broad definition of maritime archaeology as more than the research of what lies underwater, it is necessary to reflect on how representative such sites and materials might be in publications focused on, for instance, maritime trade, maritime landscape, maritime subsistence, heritage-related issues, and general historiographies of maritime archaeology. For this assessment, we need a general idea of the total extent of known and available research materials of potential maritime archaeological interest. The FHA registry lists sites by type and subtype. By using the search function, it is possible to filter out all underwater sites. In addition to 22 wrecks situated on dry land, in our estimation, the registry contains about 1300 non-underwater sites with clear maritime archaeological research potential, including maritime rock carvings, stone compasses, lighthouses and other remains of nautical signalling and navigation, channels, docks, harbours, landing sites, etc. In addition, the registry has a dedicated category for find sites, although it is very hard to estimate the proportion of find sites of possible maritime archaeological relevance. Of the 7900 listed find sites, less than 200 are underwater sites, and it is reasonable to assume that maritime archaeologically relevant find sites located above water number in the hundreds as well. This means that the known number of maritime archaeological sites both below and above water are approximately equal, but the corresponding distribution of publications reflects a clear research orientation towards the former.

Because we did not separate publications dealing with Åland specifically, the above comparison between publications and sites includes literature on Ålandic sites, but only sites under the legislation of mainland Finland. Due to their autonomy in heritage management, all heritage sites located on Åland are listed in a separate registry managed by the Government of Åland. The Ålandic registry lists about 500 shipwrecks, but it is hard to estimate the total number of sites with maritime archaeological research potential, above or below water. Given the maritime nature of the Åland Islands, it is possible that the relative proportions of maritime archaeological sites under and above water are roughly the same compared to the rest of Finland, even if the proportions between land and water areas are very different on Åland and in mainland Finland (10% and 80% land area, respectively).

As a final note, we want to reflect on the role of academia and higher education in publishing. The notably larger number of publications per year between 1995 and 2012 is also connected to the development of higher education in maritime archaeology. Whereas underwater research from the 1960s to the 1990s was mostly dependent on hobby divers, the mid-1990s saw the emergence of a generation of academically trained diving maritime archaeologists. Maritime archaeology has been taught on a small scale at the University of Helsinki, beginning in 1993 (albeit with a severe decline in the amount of taught classes since 2012), which partly contributed to the more-or-less steady flow of bachelor's and master's theses that we see starting from the 1990s. Student papers dating to the early 1990s, however, were all written at the University of Turku, where teaching of archaeology has always had a strong focus on historical times, and maritime archaeology supports that profile. Even if complete modules in maritime archaeology were only taught in Turku between 2011–2013 (Marila and Ilves 2021, 341), this short period of teaching also produced several maritime archaeological bachelor's and master's theses.

University of Turku and Helsinki alumni with a degree focus in maritime archaeology have routinely found employment in heritage management rather than in academia, where maritime archaeological research positions have always been extremely few. At the University of Helsinki, between 1993–2013, maritime archaeology was taught without any permanent staff with maritime archaeological expertise, whereas one maritime archaeologist was in charge of setting up the study module offered at the University of Turku in 2011–2013. Since 2014, only one academic position has existed in Finnish maritime archaeology (University of Helsinki). We see that the small number of maritime archaeological staff in Finnish universities offering maritime archaeological teaching is dramatically reflected in the small amount of research traceable to academic contexts. Furthermore, because small disciplines like maritime archaeology are often run with very few staff, they are easy targets for budget cuts (Marila and Ilves 2020). This hinders the long-term continuation of teaching, but also maritime archaeological research. It is therefore important not only for the amount and variability of research, but also for the existence of an entire discipline, that teaching of maritime archaeology in higher education is planned and developed with long-term continuation in mind.

One course of action to safeguard the continuation of academic research in maritime archaeology is to integrate maritime archaeological teaching with existing teaching in archaeology. This will reduce the risk of the program being shut down because of budget cuts, but it will also support the development of a wide spectrum of teaching and multidisciplinary research. Whereas research and publishing in Finnish maritime archaeology has concentrated on underwater archaeology and wrecks from the modern period (much of it published by the FHA), we see that the bibliography compiled here can serve to orientate students and researchers alike in the identification of knowledge gaps and their choice of research topics in areas that remain little researched and underrepresented in publications so far, such as the study of harbours, landing sites, waterways, and maritime landscapes and lifeways.

Viewed through its publications, Finnish maritime archaeology proper spans more than five decades. The implementation of the Antiquities Act in 1963, and the establishment of the Bureau of Maritime Archaeology at the FHA in 1968 to enforce the act, created the conditions for the professionalisation of the field. However, what we see represented in the publications is the protection and study of wrecks underwater rather than maritime archaeological research in the more general sense. This is partly explained by the close ties between heritage management and hobby divers whose interests lie primarily in the well-preserved wrecks from the historical period, but who have also been instrumental to their research in the field. This has positively led to research of modern period shipwrecks found in the coastal waters and the dissemination of knowledge thereof being one of the great strengths of Finnish maritime archaeology, a fact that is also reflected in the relatively large number of publications that deal with the nautical aspects of maritime archaeology.

We see a clear focus on shipwrecks in the publications representing the field of maritime archaeology in Finland. At the same time, by our estimate, this type of ancient monument makes up only a fraction of all sites and materials with maritime archaeological potential. Maritime sites situated on land in particular, but also underwater sites other than shipwrecks, are underrepresented in research and publications. The overrepresentation of wreck-related publications is partly explained by the great number of underwater archaeological research projects carried out at the FHA – something that we see reflected in popular publications as well – but also by the extremely small number of research positions in maritime archaeology at Finnish universities, where the academic freedom in choice of research topics would be expected to result in publications on a wide thematic spectrum.

Perhaps partly owing to the very small number of researchers in academia, Finnish maritime archaeology remains poorly represented in international arenas. On a related note, and this pertains to the future of maritime archaeological publishing in the country, the FHA, being the main actor in Finnish maritime archaeology, is not a research institution per se. Nevertheless, what we would like to see for a brighter future of Finnish maritime archaeology in terms of research visibility is more time allocated to scientific publishing in the heritage management and museum sector, where most of the country's maritime archaeological expertise is to be found. Increasing the time spent on publishing may not be important in terrestrial archaeology, where academia churns out international publications all the time, but it is very important in more marginal fields with little representation in academia, such as maritime archaeology. It is therefore also very likely that investing more time in publishing would result in more international visibility and impact for Finnish maritime archaeology.

We are thankful to everyone who responded to our call for lists of publications. The text benefited from comments by two referees and the journal editor. This work was funded by the Weisell Foundation.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.