Cite this as: Single, A. and Davies, L. 2021 Prehistory, Playhouses and the Public: London's Planning Archaeology, Internet Archaeology 57. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.57.10

As planning archaeologists at the Greater London Archaeological Advisory Service, we work to create different types of public benefit from commercial archaeological projects. Although a part of England's national heritage body (Historic England) GLAAS exists to provide archaeological planning advice to local planning authorities in London, similar to the role of County Archaeologists in the rest of England. GLAAS advises all the London planning authorities except for the square mile of the City of London itself and the London Borough of Southwark, which both have their own advisers.

Recent changes in national and regional public policy in the UK, as well as specific government initiatives resulting from those, have emphasised the aim of securing clear public benefit as an outcome of decision making. These changes include new national laws such as the Public Service (Social Value) Act, 2012, policy updates such as the 2015 government adoption of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, as well as more locally focused measures such as the Mayor of London's emerging London Plan.

In relation to archaeology, the spirit of these changes can also be traced back to the principles of the 1992 Valletta convention (Council of Europe 1992), specifically Article 9 on the promotion of public awareness. This seeks to encourage public awareness about the value of archaeological heritage for understanding the past, and seeks to promote public access to archaeological sites and finds displays. Alongside this, the application of archaeological participation to the fields of wellbeing and mental health is being increasingly discussed as a desirable outcome in heritage work (Reilly et al. 2018).

Aims around public benefit are embedded in England's National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) (Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government 2012), the policy context in which our work in managing the archaeological impact of new development, takes place. The NPPF emphasises the desirability of developers and planning authorities recognising the cultural, economic and social benefits of positive heritage management in new development schemes, encourages new development to contribute to local character and identity, and also requires developments to enhance the significance and public understanding of the heritage assets they affect.

Development since 2012 must accord with the heritage elements of the NPPF, and GLAAS encourage this from an early stage in project planning. Developer-funded archaeological investigation and arising public benefits can be included as conditions of planning consents granted under the NPPF. Sympathetic management of archaeological heritage in a final scheme can be a factor in positively determining a planning application.

The following will highlight some of the ways in which we can secure public benefit, and give some high profile examples of archaeological projects in London that are resulting in permanent cultural benefits, as well as gains for the heritage involved.

We have grouped our methods for securing public benefits into four sometimes overlapping categories.

At the most basic level, public benefit is integrated into GLAAS' day-to-day advice within the wording of our standard planning condition, which states that an approved written scheme of investigation for archaeological fieldwork must include:

… details of a programme for delivering related positive public benefits (where appropriate).

This provides developers with the opportunity to incorporate a programme of public outreach into the archaeological work phase of their project, and also gives curators a fall-back if unexpected discoveries on a site mean that it would be beneficial to the public to find out more about the site through, for example, open days, social media and talks to local interest groups. However, the general wording of the condition means the scale and ambition of the work involved is left open to interpretation by planning officials, a developer and their consultants.

For sites where there is a known high potential for archaeological remains, we have the option to prepare a bespoke planning condition in addition to the fieldwork condition, to specify that a more involved programme of public outreach is necessary. This would require its own method statement to be submitted and approved, and could, for example, contain details of the number of public open days to take place during the excavations, provision of intellectually accessible interpretative materials and holding educational activities for local schools.

For the highest profile sites, the most secure way to ensure relevant public benefit takes place is through a legal agreement such as a Section 106 agreement. This is a legally binding way of guaranteeing the resources are available to make the public benefit element happen. It applies most often to cases with significant archaeological remains that are to be preserved in situ and put on permanent display, or where part of a development scheme is to be used for cultural activities associated with the heritage of the site, for example an on-site museum or performance space.

On other sites, activities involving the public can happen in an ad hoc way, for example if outstanding and unexpected discoveries warrant extra publicity. This could take the form of a spontaneous site open day, or a press release during or shortly after the fieldwork stage. This requires goodwill from and negotiation with a developer who will be juggling various commitments and a development timetable alongside the archaeological issue. This was the case for a site we were advising on recently in Tottenham in north London.

The Welbourne site in Tottenham Hale was part of a large multi-site regeneration scheme. The archaeological planning condition had been applied a number of years ago and its wording pre-dated our current version, omitting public benefit. This meant that archaeological fieldwork and journal publication alone would satisfy the planning condition. However, once the archaeological fieldwork started, it quickly became apparent that the site contained significant and unexpected archaeological remains relating to Saxon settlement in Tottenham and some extensive early Mesolithic finds likely representing a 'home base' site.

In the resulting discussions with the developer, GLAAS and the archaeological contractors endeavoured to draw out the significance of the archaeological remains, and the benefits of opening up the site to the public as a way of letting local people, who had often been hostile to the development, know what was being found there. Despite this leading to extra work and potential delays in their development programme, the developer agreed to open up the site for a day: the morning for school groups to visit and the afternoon as a drop in session for members of the public (see Figure 1). The events were led by the site archaeological contractor, Pre-Construct Archaeology.

The archaeologists on site explained the archaeological findings to around 180 local school children in the morning, as well as describing the archaeological process. The children and their teachers were engaged and enthused about the archaeology and wanted to know more about how the landscape had looked in their local area thousands of years ago. During the afternoon over 100 members of the public attended the site, and many gave positive feedback in person and on social media (see Figure 2).

Despite the success of these visits, some issues were highlighted in running events like this in an ad hoc way. Primarily, the speed in which the organisation of the event had to take place meant there was no audience development work to target diverse groups of people, and there was no real ability to advertise the events widely. This resulted in the public open afternoon being mainly attended by people who were already heavily involved in heritage and archaeology in London through local societies or personal associations with professional archaeologists.

Historic England prepared a press release; however, the developer did not want this disseminated outside the local area, and also wanted restrictions on social media use. These are common issues that are encountered when archaeological fieldwork is ongoing on a site. Developers can be understandably guarded and cautious about letting people know what is happening on sites, especially if there is local opposition to a development as a whole. This demonstrates that there is a limit to what can be achieved when this type of event is not programmed in from the project inception. Doing something is obviously better than nothing; however, the impact is limited and public engagement work undertaken in an ad hoc way doesn't help to formalise the approach, or help to make it a fundamental element of the archaeological work as a whole.

Additionally, within commercial archaeology there are relatively few professional archaeologists who are qualified and experienced in organising, promoting and delivering events like this, and to do the face-to-face explaining of archaeology to different audiences. There are many people who do a brilliant job of stepping in, leading site tours and enthusiastically engaging people by talking about finds, but such individuals are likely to be asked to participate again and again and may not necessarily always want to do what is often a demanding and exhausting role. Although encouraged to try to count numbers of visitors, the few archaeological staff were not able to monitor entries or gather structured feedback, which was a missed opportunity from what was a popular event. While some archaeological organisations have a specific education and outreach department, for many it is not a formalised role. This highlights the crucial importance of having trained outreach staff. We are hopeful that the more opportunities for events like this that we as curators push for, the more reasons archaeological organisations will have to take it seriously and employ qualified staff.

The remaining case studies concern two preserved late 16th-century Elizabethan playhouses in the centre of London. These are sites of national importance in the UK, being some of the country's first purpose-built theatres and thus the earliest ancestors of the places where the English dramatic tradition developed, traced all the way through from the times of William Shakespeare to the modern West End today.

The first successful purpose-built public playhouse in England was called simply The Theatre and opened in 1576 in Shoreditch (Bowsher 2012). It hosted William Shakespeare's company and staged his plays at the beginning of his career. The Boar's Head was another playhouse, built a little later in 1598, that stood behind an inn of the same name near Aldgate. It has connections with many other Elizabethan theatrical figures – actors, playwrights and impresarios such as Thomas Middleton, Thomas Heywood and Will Kemp (Berry 1986).

Academic and public interest in these historical performance spaces straddles the archaeological and the theatrical sectors, something that opens up opportunities for us to connect the two fields and benefit the public's experience of both. This can include less tangible benefits such as the leverage of art and culture in a heritage context to address mental health and wellbeing matters.

We have long known the approximate locations of both playhouses from historical records, but the sites were deeply buried under 19th- and 20th-century buildings and deposits. It was only when private developers sought to build on the sites, as part of London's recent property boom, that an opportunity arose to examine and positively manage them. The sites had no legal protection at the time and were managed through the UK planning system rather than through more robust ancient monuments legislation. The Theatre has since been protected as a Scheduled Monument in UK law as a result of the developer-funded investigations carried out.

Archaeological work ten years ago first revealed the remains of the north-east corner of The Theatre, as well as some of its ancillary buildings (Knight 2013). The remains were fragmentary but still very legible. As well as the 1576 playhouse, the archaeological work showed the company's re-use of buildings and material from Holywell Priory, a medieval nunnery that preceded The Theatre.

These structures seem to have been used as the box office, prop or costume stores, or possibly as dressing rooms, helping to shed light on the operation and backstage organisation of these early sites. (see Figures 3 and 4).

The site developers are a charitable trust, and from the beginning they acknowledged the importance of the site and its archaeological remains. They wanted to include preserved remains in a design for a new, modern playhouse on the site, one that demonstrated continuity with the site's Shakespearean heritage.

A decade ago, UK public policy was not as alive to the opportunities that archaeology can offer to show off a place's distinctive character and how it can contribute to healthy, sustainable and economically vibrant communities. Policy had not caught up with archaeologists' aspirations for public benefit and focused on recording of remains and preservation without display. However, the developers wanted to preserve and enhance the site's heritage voluntarily, and Historic England supported them in pursuing their dream of building a new playhouse that respected and celebrated the old one. We hoped that the case would be an exemplar for the future, albeit a rare and very specific one. The site of the first successful playhouse in England would, we planned, become one of London's first privately funded arts and archaeology sites, with free access to the remains for the public.

The developer's aims to build a modern playhouse on a space-constrained site met many subsequent challenges, not just archaeological ones but also those relating to engineering, providing modern facilities and safety measures, meeting building height regulations in a Conservation Area and party wall issues with neighbouring properties. Four or five early design options reached us for comment, some with the remains on display in a basement, some with them covered over but visible through the floor, some with the remains left 'floating' over a deeper basement beneath.

After seven years of changing plans it became clear that the dream of building a new Theatre on the site of the old was not feasible. It simply wasn't practical to have modern fire and access provision, scope for backstage space, and catering alongside a reasonable number of seats.

New planning policy had developed in the interim too, in the form of the NPPF — policy that took greater account of developers providing demonstrable public benefit. In 2017, under this new planning policy regime, GLAAS and the developer entered into new discussions over a commercial office block at the site, instead of a new theatre. The new build was to be called The Box Office. The proposals had changed but we were now armed with new thinking and up-to-date policy about what public benefit from the scheme might look like, and these heavily influenced the result in responding to a now very commercial development.

Specialist Historic England colleagues, the developer's archaeologists (MOLA), their architects and museum consultants and GLAAS all influenced the content and practical details of the scheme as it has developed into reality. The Box Office scheme will likely open later in 2021. Figure 5 shows a mock-up of what, at the time of writing, is almost fully built and fitted out, having had its opening delayed by Covid.

Although the site will have four floors of private offices above, the ground floor will become a free to enter exhibition space, with the characteristic polygonal playhouse form beneath marked out on the ground in plan. Alongside the physical display inside, there is an extensive programme of cultural and educational events, online material and collections and curatorial input from the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Throughout the exhibition development stage, GLAAS bore in mind what we understood to be the main principles of public benefit – intellectual and physical access, an explicit schools and education aim, and also positively responding to and enhancing both the significance of the remains and the area's unique local character as London's first theatreland. This included securing links with another nearby Shakespearean playhouse, the also recently excavated Curtain Theatre, where GLAAS have helped guide the creation of public benefits in a new development, showing how one exemplar scheme can act as a spur to maximise the benefits from subsequent discoveries of the same type. Figure 6 shows a mock-up of the exterior of the new building, which at the time of writing, is almost complete.

The local council had a number of aspirations for the local street scene and public realm. They had long considered the street to be dowdy and underutilised and it was straightforward to persuade them that continuing the heritage display into the public realm could help achieve the more engaging and attractive streetscape they desired. Figure 6 also shows the planned shared space outside, with Tudor brick diapering design on the walls and pavements, the building frontage designed to look like Elizabethan theatre galleries, and a bench statue of Shakespeare himself for immortal selfies.

Despite long-term management concerns from the archaeologists, the local council were firm that a glass floor displaying some of the physical remains be included as a public benefit. As the playhouse archaeology sits on the natural geology, there are some outstanding worries regarding the illuminated display going mouldy and growing moss. The display was something that the council members would not negotiate on and so contingency to monitor and rebury the remains had been included in the consent regime, should they begin to deteriorate in the future.

The site of the Boar's Head playhouse boasted similar remains, but its circumstances were different. The site was acquired by a commercial developer of student housing who sought to build a 24-storey tower, along with a double basement beneath.

The developer's archaeological consultants had considered the possibility of encountering remains of the playhouse in their initial scoping report, but despite the positive planning and public benefit results at both The Theatre and The Curtain nearby, the proposed scheme did not envisage a need to secure more than the simplest level of public benefit from any development there, instead proposing an excavation and a report on the results.

In late 2018 when a planning application was made, GLAAS raised the issue of the playhouse and the Theatre and Curtain schemes and were not able to support the developer's original plan and recommended the proposals not be permitted in that form. Instead, GLAAS used the NPPF to require early fieldwork to characterise the remains and then inform the design of a workable new development around them, along with possible presentation.

The developers had already detailed a tightly timed plan to build quickly and open in time for a new academic year. The possibility of managing nationally important archaeology had not been factored in; however, phases of archaeological fieldwork were quickly commissioned and undertaken in order to establish the condition and extent of the playhouse remains.

These remains turned out to be more fragmentary than those at The Theatre or The Curtain and were also heavily disturbed by later developments. Additionally, they were up to 4m below modern ground level. However, with an archaeological eye and the extensive historical records of the playhouse, it was possible to identify some of the walls, the playhouse yard and the location of the stage on site (see Figures 7 and 8).

The results of the fieldwork allowed the site to be split into zones of highest, medium and lower archaeological significance (Figure 9), which led to the developer's team redesigning the scheme, eventually moving the lift cores and piles to locations outside the important playhouse zone, as well as removing the basement from the design completely. Archaeological fieldwork to investigate and record remains in other zones, where different levels of impact could be accepted, was agreed.

With a conservation-led design agreed and secured and the key remains set to be preserved in situ, it allowed us to think in detail about how public benefit might be created at a site where deeply buried and very fragmentary remains of a nationally important site were present. Given their condition, displaying the remains as found was agreed to be of an appreciable but still quite small benefit. A different approach of heritage celebration and interpretation was adopted instead.

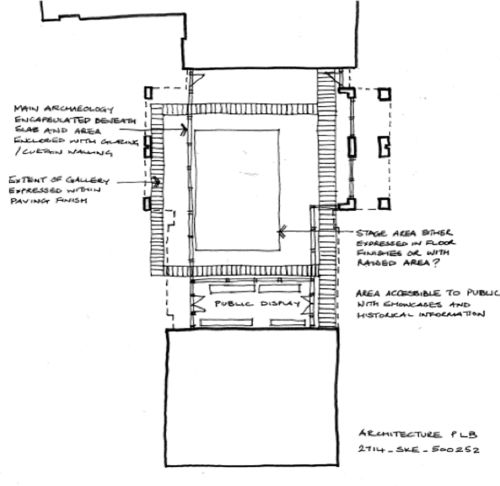

A further stage of negotiation, research and design resulted in a totally re-imagined ground floor that now includes in its centre an indoor double height space, congruent and coterminous with the playhouse that is buried safely below. The key elements of the playhouse plan are to be marked out on the ground.

This new space is planned to be commercially operated as a new cultural and performance space, as well as a café during the day, allowing extensive public access for visitors and customers. Visitors might buy a ticket to see a play being performed there in the evening, but they might also see a band, an art show or some stand-up comedy. Alongside the performance space is a discrete archaeology exhibition space so visitors will get a more traditional heritage experience too, alongside their cultural one (Figure 10). We suggest that this means that heritage is being introduced into the lives of people who might not seek out an Elizabethan playhouse for their entertainment and edification. The 400-year-old performance heritage of the site re-emerges, with the playhouse acting as a justification for the performance space and the performance space then bringing visitors to learn about the playhouse.

GLAAS formulated a bespoke planning condition for the resulting necessary fieldwork and outreach as well as a condition to control the piling works, alongside recommending a Section 106 legal covenant for the operation of the cultural spaces after completion. This includes a Management Plan that we intend will include gathering data on users and so help us determine what does and does not work about the heritage benefits of the attraction. We also intend that it will include measures to promote the heritage of the site in its advertising and, importantly, that it will identify and sustain links with schools and other key groups. Our approach is similar to that adopted by the City of London for the display of the Roman Temple of Mithras at the Bloomberg office development. However, the Bloomberg site was a far bigger and more expensive scheme, with plenty of local footfall, visible remains and commitment from the very beginning for public realm display, art and education.

In its favour as a sustainable location, the East London area surrounding the Boar's Head site already has a rich tradition of culture and creativity but the central location lacked accessible performance spaces, so the change was seen by locals and council members as a strong community benefit as well as part-mitigation for any local impacts created by the 24 floors of undergraduates soon to be living in the area. The local council officers also saw the attraction as fitting well with their aspirations for the main arterial road that the site lies on, and in its potential to draw people along that road from other attractions nearby, such as the Whitechapel Art Gallery and Brick Lane.

The archaeology of the site is therefore acting here firstly as a trigger and then as a lever to create a wider cultural and public benefit that extends beyond the archaeology itself but which feeds back into improved public understanding and enjoyment of the archaeological heritage. The importance of the playhouse means that the benefit is also one that might otherwise not be considered appropriate to require from a developer of a single building, when striking an already complex planning balance.

At the time of writing, the new tower was being constructed and is due to open in September 2021.

Because the remains were only briefly visible during the fieldwork, before being buried, a programme of public open days, walking tours, lectures and social media about the site, during the fieldwork and afterwards, was carried out by the archaeologists on site, MOLA. MOLA also produced a self-guided visitor walk between the various Elizabethan theatre sites in East London.

We have presented examples here of three of the wide variety of public benefit schemes that GLAAS have been involved with recently. Every site we encounter presents different challenges and opportunities, not only to preserve and interpret archaeological remains for public benefit, but also to introduce archaeology into people's cultural, educational and recreational lives when they might not be expecting it, or even looking for it.

We can even achieve this when there is no formal requirement for it and when the archaeology is poorly preserved or almost illegible, through negotiation and by focusing on other ways to leverage it that complement wider policy aims and public benefit objectives. In turn, these resulting attractions will improve public understanding of that heritage.

Sometimes, we can go further and create a tangible economic asset, one that can even operate commercially, creating quantifiable benefits that developers and decision makers understand: 'jobs', 'public events', 'customers' etc. As the sites become operational and we collect more experience and data in this field, we can begin to try to put a clearer balance sheet value on sympathetic archaeological heritage management. We can draw on the Wellbeing agenda to support us too and create benefit in allied areas.

The examples of the Elizabethan playhouses when they are completed will, we hope, increasingly help to convince decision makers of the potential of archaeological preservation, display and interpretation as a 'gain'. This is a young field and we sometimes struggle to convey the potential of this area to others in the development industry but each successful new project builds our case and raises the profile of archaeological sites in London. In the future, we hope that structured collection of user data, derived from the marketing exercises and visitor surveys that the sites will carry out will help inform new schemes and shed light on what does and what does not work in creating sustainable public benefits. At present we can look at established tourist attractions for help and data, but currently there is little comparative information to draw on from successful developer-funded archaeological attractions.

Maintenance and upkeep can be secured through planning agreements, and in some cases commercial operation can provide an impetus to seek out and attract audiences. We are mindful of the failures of past efforts to engage the public with heritage in London – outdated and vandalised interpretation boards, medieval walls left crumbling in office basement car parks, jargon-filled leaflets — and want to find a way to leave the sites that we find well managed for everyone's benefit.

Today, there are few archaeologists with more than a site or two like the East London playhouses under their belts to draw experience from. Designing public benefit schemes and managing archaeological attractions is a specialism in itself, and the need for these skills must be considered from the outset of a project, instead of sometimes being seen as an add-on obligation to be done to minimum standards. Planning archaeologists, archaeological planning consultants and fieldwork units certainly do not possess all the skills to design and run a successful visitor attraction or commercial venue.

We think therefore that there is an interdisciplinary skills and resourcing gap here that needs addressing, alongside the willingness of UK planning archaeologists to be ambitious enough to ask for these sorts of benefits in the first place. It is no coincidence that common issues regarding an absence of agreed benchmarks for success, common guidance and appropriately trained archaeologists have also been identified in UK community archaeology (e.g. Simpson and Williams 2018; Frearson 2018).

The wording of the NPPF allows for the incorporation of public benefit schemes into archaeological projects in the UK, and these can be secured through the planning system and legal agreements. Our involvement in aspects of public benefit schemes such as site open days has highlighted the disparity in the ability of archaeological contracting units and their clients to always plan and deal effectively with this work. There is a clear lack of suitably skilled staff in many organisations, and we have a long way to go in considering reaching diverse audiences, or in collecting data about those who have visited sites and attended events.

The authors would like to thank all the archaeologists involved (RPS, PCA, MOLA) for both their hard work on site and their invaluable interpretations of the finds. We would also like to thank Gallus Studios and PLB Architects for their work in developing public benefit ideas into concrete proposals. Finally, we are grateful to Nina Dierks for her editing work and helpful comments on improvements to the text of this article. Any remaining errors are those of the authors.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.