Cite this as: Petrauskas, G., Muradian, L. and Kurilienė, A. 2024 Archaeology of Modern Conflict and Heritage Legislation in Lithuania during Thirty Years of Restored Independence, Internet Archaeology 66. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.66.13

Comprehensive archaeological investigations of 20th-century conflict sites, which began more than two decades ago, have changed the way researchers approach modern conflicts, revealing the vast possibilities for their study and expanding the boundaries of archaeology. Recent research projects, conferences and publications have shown that archaeology of modern conflicts has already become a distinct field of archaeology. However, the significance of 20th-century conflict sites is more than academic. These sites are inextricably linked to the politics, memory and identity of local communities, and they receive considerable media interest and stir a range of public emotions (González-Ruibal 2007; Moshenska 2009; Thomas 2019).

Countries have different regulations for the protection and excavation of modern conflict sites. In some of them, procedures for the exhumation of victims of 20th-century conflicts are already in place (cf. Thannhäuser et al. 2021). In others, however, the legal framework for the investigation of modern conflict sites is still in the process of being developed and archaeological research is not sufficiently regulated. Research is often constrained by arms and explosives control laws and faces political, ethical and other challenges (Moshenska 2008; Wijnen et al. 2016; González-Ruibal 2017; van der Schriek 2022). In the Netherlands, for example, archaeologists are not allowed to examine the remains of victims of 20th-century conflicts, and their exhumation is only carried out by a specialised unit of the Netherlands Armed Forces (van der Schriek 2022). Today, research on the First and Second World Wars, the Holocaust and the anti-Nazi resistance, the Spanish Civil War and the Cold War is an integral part of archaeological scholarship and cultural heritage management projects (Saunders 2010; Sturdy Colls 2012; Moshenska 2013; Hanson 2016; González-Ruibal 2020).

After the Lithuanian National Revival in 1988 and the restoration of independence in 1990, the public on their own initiative searched for the remains of fallen anti-Soviet Lithuanian partisans (1944-1953), excavating the burial sites of partisan remains, their bunkers and dugouts (Petrauskas and Petrauskienė 2020). Therefore, by the beginning of the 1990s, the procedure for the investigation and exhumation of the victims of 20th-century conflicts and occupation regimes was already established. Over the last decade, the sites of the Lithuanian Partisan War as well as the First and Second World Wars have become the subject of scientific research (Jankauskas et al. 2005; 2011; Jankauskas 2009; 2015; Petrauskas et al. 2018; Petrauskas and Ivanovaitė 2019; Petrauskas and Petrauskienė 2020; Čičiurkaitė and Kraniauskas 2022b; Jankauskas and Kisielius 2022; Kozakaitė 2022; Vėlius 2022; Petrauskas forthcoming). The increasing scale of archaeological research in modern conflict sites has led to the need to review and amend the legal documents regulating their investigation and to concerns about the improvement of the legal protection system. This article focuses on 20th-century conflict sites in Lithuania, examining issues of their protection, heritage conservation and archaeology, as well as current trends in archaeological research methodology.

After the end of the First and Second World Wars, the exhumation, burial and commemoration of the remains of war victims began in many countries. The exhumation of Second World War victims was an attempt to record evidence of war crimes, which gave it a legal subtext and was often used for propaganda purposes (Raszeja and Chróścielewski 1994; Paperno 2001; Ferrándiz and Robben 2015). In Lithuania, as in other European countries, several excavations of Holocaust mass graves were carried out between 1951 and 1963. However, the exhumations ordered by the Soviet occupation authorities did not include a detailed scientific analysis, but only a determination of the number of persons killed, their age, gender and signs of violence (Jankauskas 2009; Jankauskas and Kisielius 2022). Although these exhumations are considered to be the origins of forensic archaeology in Lithuania, their purpose was political. The aim was to gather evidence for the trial of the Nazi regime's crimes against so-called Soviet citizens (the nationality of the victims was deliberately concealed).

The remains of tens of thousands of Red Army soldiers exhumed during the Soviet occupation were buried in military cemeteries scattered throughout Lithuania (Arlauskaitė-Zakšauskienė et al. 2016). In 1954-1955 and later, great attention was paid to searching for the remains of Soviet partisans (anti-Nazi resistance fighters) and their transfer to military cemeteries (Zizas 2014). The remains of Red Army and Wehrmacht soldiers have been accidentally discovered several times during archaeological research (Katalynas and Vitkūnas 2013; Arlauskaitė-Zakšauskienė et al. 2016). Unlike the former, the remains of the Wehrmacht soldiers were taken by the Soviet authorities, and their fate is unknown today. The newly established Red Army cemeteries, as well as the restored Red Army's dugouts that have become independent museums (Zizas 2014; Petrauskienė 2016), show how modern conflict sites have been exploited for political and propaganda purposes during the Soviet occupation.

The decade-long Lithuanian Partisan War took the lives of more than 20,000 freedom fighters (Jankauskienė 2014). The desecrated remains of the killed partisans were secretly buried in the courtyards of Soviet security headquarters, as well as in gravel pits, swamps, peat bogs, latrines, wells, and other disrespectful places. The Soviet regime kept the mass graves secret, and to hide the graves, landfills, parks and sports grounds were built, land reclamation was carried out and ponds were dug (Striužas 2021). In 1988, with the onset of the Lithuanian National Revival and the thawing of the political climate, the burial sites of partisan remains attracted a great deal of public attention. The relatives and comrades of the partisans began to search en masse for the remains of the freedom fighters, exhume and transfer them to cemeteries.

The exact number of partisan remains exhumed and reburied in cemeteries is unknown, but there is no doubt that the most extensive searches and excavations took place in the late 1980s and early 1990s (Varnaitė 1996). It is estimated that the remains of around 2000 resistance fighters were transferred to cemeteries, 95% of which were unearthed without the participation of specialists (Pečiūraitė 1992). On the other hand, between 1988 and 1997 members of the largest Lithuanian Union of Political Prisoners and Deportees alone exhumed the remains of 1964 partisans and transferred them to cemeteries (Juškevičienė 1998).

Excavations of the burial sites of victims of the Soviet regime were chaotic. Procedures and excavation techniques were not followed during the exhumation process. The remains were often removed with the help of mechanical excavators, the bones mixed, boxed and buried in collective graves (Figure 1). The damage caused by such exhumations was considerable. The recovered remains of partisans remained unidentified, physical evidence of the cause of death was destroyed, and the possibility of prosecuting the perpetrators of the crimes and of appealing to international courts for the restoration of justice was lost. In 1989, archaeologists of the Lithuanian Institute of History and anthropologists of Vilnius University prepared a memorandum on the procedure for exhumation of human remains (Urbanavičius 1999), and attempts were made to inform the public about the harm caused by unauthorised excavations (Česnys 1991).

The legal protection of freedom fighters buried in cemeteries began to be discussed as early as 1990 (Petrauskienė 2022), and the issue of the exhumation of partisan remains soon received state attention. In 1991, the Presidium of the Supreme Council of Lithuania, and a year later the Government of Lithuania, adopted two resolutions regarding the relocation of remains (Resolution of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the Republic Lithuania 1991; Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania 1992) which laid down the procedure for exhuming and transferring the remains of people killed by the occupation regimes of the 20th century. The resolutions stated that the exhumation procedure should involve a prosecutor, an archaeologist, a forensic medical expert and, if necessary, an anthropologist. Before the exhumation process could begin, a new burial site had to be selected and special technical, sanitary and legal conditions had to be ensured. Moreover, the exhumation had to comply with the basic requirements of archaeological research and the identification of the recovered remains had to be carried out in accordance with forensic methodology. However, the general conditions applied only to the exhumation of human remains buried in disrespectful places. In other cases, the initiators of the transfer of partisan remains had to obtain additional consent from the Commission for the Relocation and Commemoration of Burial Sites and the Government of Lithuania.

In 1996, an agreement was signed between the governments of Lithuania and Germany on the maintenance of the graves of German soldiers in the Republic of Lithuania (Agreement between the Government of the Republic of Lithuania and the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany 1996). The agreement established the procedure for the transfer of the remains of German soldiers to cemeteries and ensured that graves of German soldiers in Lithuania were protected. At the same time, the bilateral agreement between Lithuania and the Russian Federation regarding the graves of Russian soldiers has not yet been adopted and, in the current geopolitical climate, is unlikely to be signed at all (Arlauskaitė-Zakšauskienė et al. 2016).

After the adoption of the procedure for exhuming and transferring human remains to cemeteries, archaeological investigations of the burial sites began (in some cases, archaeologists were involved in the exhumation of the partisan remains even before the adoption of the aforementioned resolutions, cf. Rimkus 1996). The first permit to conduct archaeological research at the burial site of partisan remains was issued only in 1996, and there is a lack of even the most general data on the exhumations that took place prior to that year (Petrauskienė and Petrauskas 2014). These excavations were poorly documented, the required research methodology was not always followed, and the burial sites of partisan remains were not considered an object of Lithuanian archaeology. Moreover, the regulations and procedures for exhuming human remains were often violated by relatives of the deceased and representatives of public organisations (Varnaitė 1996).

In 1994, following the establishment of a state commission by a decree of the President of Lithuania, detailed archaeological investigations were carried out in the park of the former Tuskulėnai Manor in Vilnius, where the remains of a total of 724 resistance fighters were discovered. They had been executed in the cellars of Vilnius NKGB/MGB (Ministry of State Security) internal prison between 1944 and 1947 . Interdisciplinary research, combining archaeological, anthropological, forensic and historical data, has resulted in the identification of more than 60 of these individuals (Jankauskas et al. 2005; Jankauskas 2009; 2015; Bird 2013; Jankauskas and Kisielius 2022). These investigations not only laid the foundations for targeted searches for partisan remains and burial sites coordinated by state institutions, but are also considered the beginning of forensic archaeology and forensic anthropology in Lithuania.

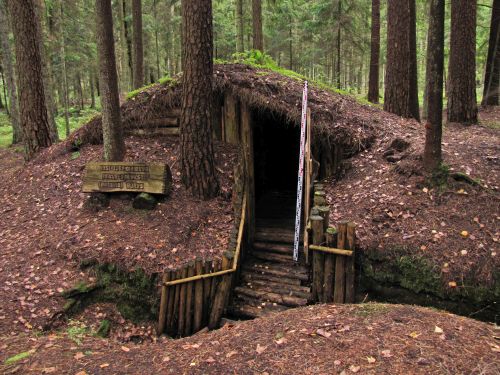

After the restoration of Lithuanian independence, former partisans, their couriers and supporters, as well as political prisoners and other survivors of Soviet repression, initiated the excavation and restoration of partisan bunkers and dugouts. These locations were seen as places of partisan sacrifice and death, and their restoration represented an effort to honour and commemorate the fallen partisans and their struggle for freedom (Petrauskienė 2022). Since 1991, a total of about 50 partisan bunkers and dugouts have been excavated and reconstructed in Lithuania, of which about 80% have been restored in their original locations (Petrauskienė 2016) (Figure 2). Most of the reconstruction work took place in the 1990s and early 2000s. The restored bunkers and dugouts, many of which were important headquarters of partisan districts and detachments, and places of death of high-ranking partisans, were completely destroyed during the process of amateur excavations and reconstructions. The structures unearthed went unrecorded, and unique archaeological finds were not collected and are now lost.

Unlike the exhumation of partisan remains, no concrete action was taken to protect the partisan bunkers and dugouts. For a long time, they did not receive the attention of researchers, and the need for archaeological research prior to reconstruction works was only foreseen for bunkers and dugouts that were protected by law. At that time, only a small number of partisan bunkers and dugouts had legal protection status (see below). In 2010, for the first time in Lithuania, archaeological investigations of partisan bunkers were carried out on the initiative of state institutions and individual researchers (Petrauskas and Petrauskienė 2020; Vėlius 2022). These investigations became a turning point in Lithuanian archaeology and changed the way researchers approached the sites of modern conflict and their relationship to archaeology. They also created the preconditions for changing the legal regulation of these sites and their research.

In Lithuania, there have been significant changes in the chronological boundaries of archaeological heritage over the last 50 years. In 1976, archaeological heritage was considered to be anything dating before the end of the 16th-17th centuries. However, in 1992, this boundary was extended to the 18th century (Augustinavičius and Poškienė 2015). Subsequently, in 2005, the upper chronological limit for archaeological heritage was further expanded to the first quarter of the 18th century (c. 1711-1721). Finally, in 2011, this limit was pushed forward to the 19th century (Order of the Minister of Culture of the Republic of Lithuania 2005; 2011). This chronological boundary was incorporated into both secondary legislation regulating the evaluation and selection of immovable cultural property and the methodology of archaeological research.

Presently, the legislation regulating the methodology of archaeological investigations defines an archaeological layer as a scientifically valuable cultural layer dating back to 1800, within which archaeological finds or structures are discovered. However, the Law on the Protection of Immovable Cultural Heritage (2004) does not specify the chronological limits for considering finds as archaeological. This law defines archaeological finds as objects or remnants of objects created by humans or bearing signs of human presence, discovered during archaeological investigations or through other means, and possessing scientific value for historical knowledge. Archaeological finds also include human remains from ancient times. In comparison, in neighbouring Estonia, artefacts dating back to the 18th century are considered to be archaeological finds, but 20th-century conflict finds of cultural and scientific value are not subject to age limits (Kadakas 2020).

It should be noted that protected immovable cultural heritage dating back to the 19th and 20th centuries listed in the Register of Cultural Property usually has other valuable features not related to archaeology, such as architectural, historical, or memorial. Nevertheless, the legislation governing the obligation to conduct archaeological investigations stipulates that, in certain cases, even on sites with no archaeological value, archaeological research methods must be applied prior to any excavation works. The requirements for mandatory archaeological investigations and the methodology of these investigations are outlined in the Archaeological Heritage Management Regulation (Order of the Minister of Culture of the Republic of Lithuania 2011; 2022), which was initially approved in 2011 and subsequently updated in 2022.

In 2011, the Archaeological Heritage Management Regulation, among other cases of mandatory archaeological investigations, provided that archaeological research is required in the course of excavation works at the burial sites of persons killed during the 19th- and 20th-century resistance, armed conflicts (wars and uprisings), and the occupation regimes (Order of the Minister of Culture of the Republic of Lithuania 2011). Such investigations are mainly related to the exhumation of remains, which is also regulated by the Law on the Burial of Human Remains of the Republic of Lithuania (2007) and the resolution on the procedure for the relocation, commemoration or marking of the burial places of resistance fighters (Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania 2016). This replaced the Resolution on the relocation and commemoration of remains which had been in force since 1992. The new document defines the period of the occupation regimes as 1920-1939 in Vilnius region and 1939-1990 in Lithuania as a whole (no mention is made of the exhumation of the victims of the First World War and the relocation of their remains). In contrast to the previous Resolution, the latter mostly refers to the relocation of accidentally discovered remains, but does not specify the procedure for exhumation of these remains and the mandatory participation of an archaeologist in their exhumation (Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania 2016). However, since the adoption of this law, more institutions have become involved in the exhumation procedures, and the compulsory participation of an archaeologist in the exhumation of these remains has been in force since 2011, when the Archaeological Heritage Management Regulation was approved.

The current legislation provides that the remains of resistance fighters and other persons killed during the occupation regimes must be reburied in accordance with the procedure established by the Government of the Republic of Lithuania, in coordination with its authorised institutions (Law amending Article 25 of the Law of on the Burial of Human Remains 2014). If necessary, municipal executive authorities can establish temporary commissions for the transfer of remains, commemoration or marking of the burial site. They include representatives of municipalities, the Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania, organisations of freedom fighters and other organisations and institutions. Among these institutions are the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Lithuania (in the case of commemorating or marking the burial sites of the remains of persons from other countries), the Lithuanian Jewish (Litvak) Community (in the case of the remains of Jewish persons), and the Department of Cultural Heritage under the Ministry of Culture (if the burial site to be commemorated or marked is located in the territory of an immovable cultural heritage object). If the identity of the discovered remains is established, the relatives of the deceased must also be included in the commission (Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania 2016). Additionally, as of the 2022 Archaeological Heritage Management Regulation, if the presumed remains of participants of the Lithuanian Partisan War are discovered, it is a requirement to take samples for DNA testing (Order of the Minister of Culture of the Republic of Lithuania 2022).

As the field of research on 20th-century conflict sites is expanding and in order to draw attention to the need to extend the part of the Archaeological Heritage Management Regulation related to the regulation of research on 20th-century conflict sites, in 2012, by Order of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Lithuania, the Working Group on the Preservation of Museums of Deportations, Resistance and Restored Partisan Bunkers was established (Petrauskienė 2017). Although the proposals made by the working group regarding the reconstruction of Lithuanian partisan bunkers and dugouts, legal responsibility, and stricter control over restoration works were not immediately approved, a significant step was taken towards strengthening the regulation of research on the sites of 20th-century conflicts.

Of particular significance is the Letter issued by the Centre of Cultural Heritage (2019) to relevant stakeholders, regarding the protection of partisan bunkers and dugouts. This letter states that the restoration of partisan bunkers and dugouts should be coordinated with specialists from the Department of Cultural Heritage under the Ministry of Culture, and recommends that reconstruction activities should be focused on sites that do not have the status of legally protected objects, rather than on identified and recognised sites. Furthermore, it was also suggested that archaeological research should be carried out on these sites prior to beginning any restoration work.

The proposals made by the Working Group and the Centre of Cultural Heritage regarding the regulation of 20th-century conflict sites were incorporated into the updated Archaeological Heritage Management Regulation (Order of the Minister of Culture of the Republic of Lithuania 2022). One of the articles of the Regulation states that archaeological research in Lithuania is obligatory for excavation works at all places of resistance and armed conflicts of the 19th and 20th centuries, such as sites of massacre, death, battles, camps, shelters, memorial homesteads, bunkers, trenches, etc. The aim of this provision is to collect detailed data for the conservation and restoration of these sites while also providing the public with access to significant heritage sites related to modern conflicts.

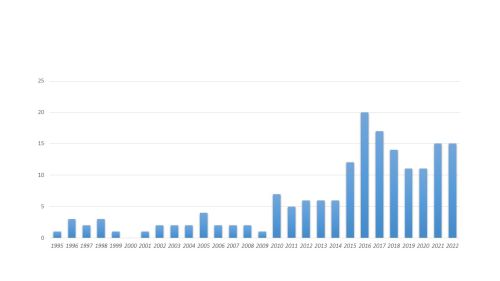

The implementation of the Archaeological Heritage Management Regulation in 2011 has led to a significant increase in the number of permits issued for archaeological investigations at 20th-century conflict sites. Between 1995 and 2022, the Department of Cultural Heritage under the Ministry of Culture granted a total of 171 permits for archaeological research at these sites: 33 permits were issued before 2010 and 138 permits were granted between 2011 to 2022 (Figure 3). The number of permits issued has quadrupled since the adoption of this legislation, but it is worth noting that the overall number of archaeological investigations has also steadily increased year on year. Before 2010, an average of 240 permits were issued annually, while between 2011 and 2022, the average number of permits granted annually was 491.

The proportion of archaeological investigations carried out at 20th-century conflict sites has fluctuated over the last decade, representing 1.2% to 3.9% of the total number of permits issued each year. However, it should be emphasised that the recent increase in the number of permits issued for archaeological investigations at 20th-century conflict sites can be attributed not only to the requirement to carry out such investigations prior to excavation works at sites related to 19th- and 20th-century resistance and armed conflicts, as mandated by the Archaeological Heritage Management Regulation, but also to the emergence of the scientific field of modern conflict archaeology.

In Lithuania, archaeological excavations have been carried out at various sites of 20th-century conflicts, including First and Second World War fortifications, graves of Wehrmacht and Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa) soldiers, burial sites of Lithuanian partisans, bunkers, dugouts, battlefields, campsites, sites related to the massacre of the Jews, and labour camps (Figure 4). The majority of these investigations are focused on the search and exhumation of remains, but the objectives of research on 20th-century conflict sites also include the collection of scientific data, the adjustment of the valuable properties of immovable cultural heritage sites, and the adoption of decisions on the conservation, restoration and public presentation of these sites.

One of the largest exhumations of remains in recent years involved archaeological research carried out in and around the territory of the Macikai Nazi POW camp and the Soviet Union Gulag complex in the Šilutė district. The Government of the Republic of Lithuania officially approved the concept and action plan for the restoration of the Macikai complex. The main objective of this initiative is to preserve the historical memory of the crimes committed by the totalitarian Nazi and Stalinist regimes in the middle of the 20th century for future generations, and to commemorate the victims who were murdered there.

The Macikai mass grave is located in the village of Armalėnai, approximately 1.5km south of the site of the Macikai POW camp. Human remains were first discovered at this site in 2011, and geophysical surveys were later carried out to determine the possible boundaries of the burial site (Abromavičius 2020). In 2020, the remains of 1199 people were found and exhumed in an area of 808.65 sq m (Čičiurkaitė and Kraniauskas 2022b). After the research, these remains were reburied in a newly formed area near the cemetery of the former POW camp in Macikai. In 2021, additional archaeological investigations were carried out in order to obtain more precise data on the number, period and area of the burials of the Macikai POW camp. The remains discovered during these investigations were not removed and anthropological research was carried out in situ (Čičiurkaitė and Kraniauskas 2022a). In 2022, after the possible boundaries of the cemetery territory were established, the data of this immovable cultural heritage object were revised in the Register of Cultural Property. The boundaries of the protected area were extended and the description of the site's valuable properties was adjusted.

The second important field of archaeological research is the commemorative sites of 20th-century conflicts. These include Lithuanian partisan bunkers, dugouts, campsites, battlefields, homesteads, and fortifications of the First and Second World Wars. The first archaeological investigations of partisan bunkers were carried out in 2010, and based on the data from this research, bunkers were reconstructed in two places: Daugėliškiai Forest (Raseiniai district) and Minaičiai village (Radviliškis district) (Petrauskas and Petrauskienė 2020; Vėlius 2022). These excavations have revealed the significance of archaeological research, showing how it supplements, corrects and even alters historical information and eyewitness memories.

The reconstruction of partisan bunkers and dugouts in their authentic locations is a constant challenge for heritage management. Recently, there has been much debate about how to preserve the authentic features of bunkers and dugouts during restoration procedures. Considering that archaeological research is a destructive research method, it is recommended to use the least invasive research methods possible.

One notable example is the archaeological research carried out at the Blinstrubiškiai Forest partisan dugout (Raseiniai district). In 2014, the Department of Cultural Heritage under the Ministry of Culture suspended the restoration works after the unauthorised reconstruction of the dugout had started. Later, in 2015, the dugout was legally protected and included in the Register of Cultural Property. Following the legal protection of the dugout, further works were coordinated with the heritage authorities in advance. In 2017, the Raseiniai District Municipality started planning the archaeological investigation and restoration of the partisan dugout. One of the authors of this article proposed that the original structures should not be excavated; instead, a series of boreholes were drilled into the dugout pit using a geological drill, and the surrounding area was surveyed with a metal detector. These research methods were used to determine the height of the dugout and the type of wood used for construction, and numerous finds were collected during the metal-detector survey. All the data collected, including the findings of the metal-detector survey and the geological drill, provided valuable information about the battle that took place at the Blinstrubiškiai Forest partisan dugout (Petrauskas and Petrauskienė 2018).

Following archaeological investigations, it was suggested that the reconstruction of the dugout should take place outside the protected area of the cultural heritage site, rather than in the original location. This recommendation sought to balance the conservation of the original authentic site with the public access to and understanding of its historical significance. In addition, it was proposed to create a public display presenting the results of the archaeological and historical research carried out on the site. This display would enable the public to see the results of the research and learn about the historical context and significance of the dugout.

The concept of cultural heritage in Lithuania throughout the 20th century depended on the political situation. The systematic development of Lithuanian heritage protection and the formation of the concept of cultural heritage, which began in 1919, was interrupted because of the Second World War. During the second Soviet occupation (1944-1990), it depended on the ideology of the Soviet Union and their attitude towards the period of the history of independent Lithuania, the 20th-century freedom fights and resistance (Čepaitienė 2005). During the occupation, when Lithuanian heritage protection was developed in accordance with Soviet legislation and was fully integrated into the Soviet Union's heritage protection system (Glemža 2002), the objects of modern conflicts were highly politicised and reflected the Soviet ideology of 'class struggle'. In the then Soviet Lithuanian list of cultural monuments, which was unsystematic, biased and intended for official rather than public use (Bučas 1993), about half of the historic cultural heritage sites comprised cemeteries of Soviet soldiers and buildings where Soviet security headquarters were established and 'revolutionary' and executive committees of the government functioned (Imbrasienė 1973).

With the beginning of a Lithuanian National Revival in 1988, the impact of the Soviet occupation on Lithuanian cultural heritage and the loss of cultural heritage was highlighted. Public attention was drawn to the sites of modern conflicts that bear witness to liberation, resistance to the occupying regimes and the struggle for freedom as a crucial element of the country's historical memory. After the restoration of independence in 1990, although the concept of modern conflict sites had not yet been clearly defined, these sites gradually began to be integrated into the Lithuanian heritage protection system i.e. the accounting and protection of cultural heritage objects.

The first Law on Protection of Immovable Cultural Properties of the Republic of Lithuania (1994) specified that redundant cemeteries, military cemeteries and other objects of cultural value and social significance shall be registered in the Register of Immovable Cultural Property (now the Register of Cultural Property). Sites of modern conflicts (Holocaust sites, Lithuanian partisan battle and death sites, partisan graves, etc.) were classified and registered in the Register of Immovable Cultural Property as Sites of Events and Burial Sites. Such sites were given identical protection as other immovable cultural heritage. Only later, in 2002, after taking into account the specificity of individual types of immovable cultural heritage, were Standard Protection Regulations for individual groups of immovable cultural heritage approved, including the Standard Protection Regulation for the Protection of the Event, Burial and Mythological Sites of Immovable Cultural Property. It laid down the conditions for the maintenance, management and use of the Event and Burial sites (Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania 2002).

However, the major breakthrough in the field of assessment, accounting and protection of modern conflict sites was brought about by the adoption of the new revision of the Law on the Protection of Immovable Cultural Heritage (2004) and the accompanying legal acts. The new law regulated the classification of immovable cultural heritage according to the nature of their valuable properties or a combination of valuable properties that determines their significance. It defined the types of properties of historical (sites or places recognised as significant in relation to important events or personalities in the history of society, culture and the state, or made famous by literature or other works of art) and memorial (sites intended to commemorate significant events or personalities in the history of culture and the state) value, which are generally attributed to sites of modern conflict. Regulations ensure that memorial objects of cultural heritage, burial places of the dead, and memorial sites (cemeteries or individual graves of soldiers, uprising participants, resistance fighters, and other unused cemeteries) shall be protected for the purposes of public respect.

With the establishment of the current Register of Cultural Property in 2005 and the approval of the Description of the Criteria for Evaluation and Selection of Immovable Cultural Property, the evaluation and accounting of modern conflict sites has intensified significantly (Order of the Minister of Culture of the Republic of Lithuania 2005; Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania 2005). The latter regulated the assessment of immovable cultural heritage, its criteria and their application in determining the valuable properties and significance of cultural heritage objects or sites, in defining their territories, in selecting immovable cultural heritage for legal protection, and in submitting it for registration in the Register of Cultural Property. The increased accounting of modern conflict sites has been significantly influenced by the public interest in Lithuanian Partisan War sites (including individual initiatives to manage such sites), scientific research, state cultural policy and strategy, and the activities of institutions dedicated to the investigation of crimes committed against the Lithuanian population during the occupation period, and the perpetuation and preservation of the historical memory that population (Table 1). In addition, the efforts to assess and legally protect a group of cultural heritage sites that had previously received insufficient attention played an important role.

| Commission for Freedom Fights and State Historical Memory of the Parliament of the Republic of Lithuania | The Commission coordinates the strategy and directions of the policy for the preservation and commemoration of the state's historical memory, taking into account the interests of the state; within the scope of its competence, it coordinates the activities of the institutions responsible for the preservation and commemoration of historical memory. |

| Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania | The Centre investigates the physical and moral genocide of the Lithuanian population and the resistance to these regimes committed by the occupation regimes between 1939 and 1990, commemorates the freedom fighters and the victims of the genocide, and initiates a legal evaluation of the consequences of the occupation. |

| National Commission for Cultural Heritage of the Republic of Lithuania | The Commission is an expert and advisor to the Parliament, the President and the Government of the Republic of Lithuania on issues related to the state policy for the protection of cultural heritage, its implementation, evaluation and improvement. It participates in the formulation of the policy and strategy for the protection of cultural heritage, and provides opinions on the classification of cultural heritage objects as state protected and cultural monuments. |

| Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Lithuania | The Ministry formulates national cultural policy for the protection of cultural property. |

| Department of Cultural Heritage under the Ministry of Culture | The Department carries out the functions of protection of immovable and movable cultural heritage and is responsible for their implementation. |

| Public institution 'Cultural Property Protection Service | The institution carries out the actions provided for in the Agreement signed between the Republic of Lithuania and the Federal Republic of Germany on the exhumation and reburial of the remains of German soldiers. |

| Academic, research institutions and researchers | Research related to scientific projects, programmes and research interests. |

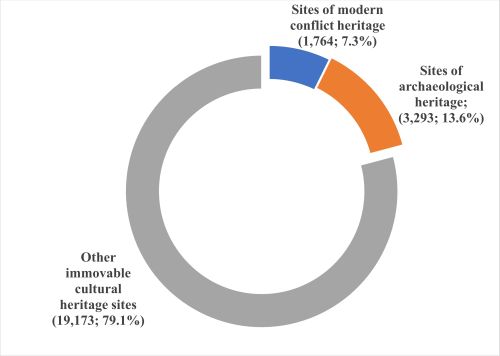

The legal regulation of the Department of Cultural Heritage under the Ministry of Culture for the assessment of the immovable cultural heritage and the planning of the accounting of the immovable cultural heritage have resulted in the registration of 1764 immovable cultural heritage objects related to modern conflict sites in the Register of Cultural Property (as at July 2023; Figure 5). This represents 7.3% of all immovable cultural heritage sites. In comparison, archaeological sites that have escaped ideological evaluations and have been inscribed and/or registered in various lists of cultural heritage monuments since the late 19th and early 20th centuries account for 13.6% of the total number of immovable cultural heritage in the Register of Cultural Property.

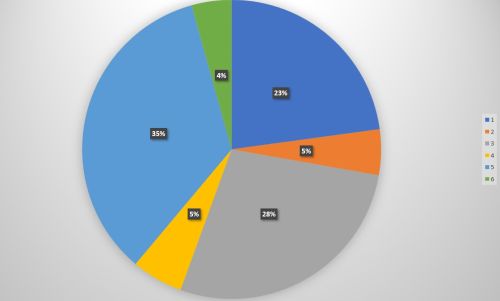

Modern conflict sites include the sites of the First and Second World Wars, the Lithuanian Wars of Independence (1918-1920), the Lithuanian Partisan War (1944-1953), and the Soviet and Nazi occupations. The cultural heritage objects registered in the Register of Cultural Property are divided into several generalised groups of modern conflict sites. These include: 1) fortifications, forts and bunkers (n=61 or 3.5%); 2) graves and burial sites of German and Russian soldiers of the First World War, Polish soldiers of the Lithuanian Wars of Independence period, and soldiers of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union of the Second World War (n=350 or 19.8%); 3) Holocaust sites (n=202 or 11.5%); and 4) sites related to the Lithuanian Wars of Independence, the 1941 Uprising, the Lithuanian Partisan War, the repressions of the Soviet occupation regime, as well as the restoration of Lithuanian independence and the defenders of freedom (1990-1991) (n=1139 or 64.6%) (Figure 6).

The largest and most attention-grabbing group is represented by the Lithuanian Partisan War sites. A total of 730 Partisan War sites are listed in the Register of Cultural Property, representing 41.4% of all modern conflict sites. A further 48 sites (2.7%) commemorate Soviet and Nazi terror, some of which are also linked to the Lithuanian Partisan War. The accounting and registration of Lithuanian Partisan War sites improved significantly in 2014 with the establishment of the Fifth Council for the Evaluation of Immovable Cultural Heritage under the Department of Cultural Heritage (in 2015, Partisan War sites accounted for only 2.4% of all cultural heritage properties; Petrauskienė 2017).

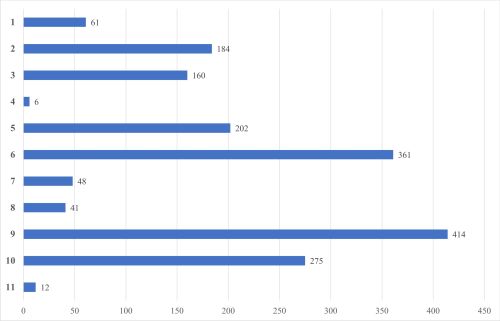

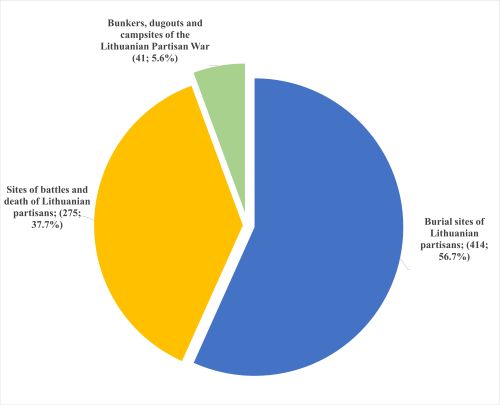

Although the registered Lithuanian Partisan War sites include partisan bunkers, dugouts, campsites and battlefields, the majority of the recorded sites are partisan death sites, graves and disposal sites (Figure 7). It should be noted that Partisan War sites can often fall into several categories (for example, partisan bunkers and dugouts can be considered as both battlefields and death sites), and therefore, depending on the criteria chosen, their classification into one or the other group may vary. However, the analysis of the Register of Cultural Property reveals that the heritage protection of Lithuanian Partisan War sites is mainly based on the image of death (sacrifice), while other Partisan War sites that stand out in the landscape have not yet received due attention (Petrauskienė 2022).

The total number of modern conflict sites listed in the Register of Cultural Property and the number of sites by group are variables owing to the ongoing accounting process. In any case, the Register of Cultural Property will never reflect all 20th-century conflict sites. For example, some of the remains found and identified are immediately exhumed and transferred to cemeteries, and these sites are not granted legal protection or registered in the Register of Cultural Property.

Considering the accounting and protection of modern conflict sites in Lithuania over the last three decades (1990-2022), it can be said that this group of cultural heritage objects, which is significant for society and important for the historical memory of the state, has received a considerable amount of attention from both the public and state institutions. During this period, the protection and evaluation of these cultural heritage sites, the obligation to carry out archaeological research, and the rapid accounting of the heritage of conflicts (especially the Lithuanian Partisan War) were all regulated by law. However, in order to protect as many 20th-century conflict sites as possible, there have inevitably been hasty or no decisions taken, and there was a lack of debate in some cases, which continues to pose challenges for heritage protection.

One of the challenges for heritage protection in Lithuania today is the insufficient regulation of the concepts of historical and memorial valuable properties, the lack of clear criteria for the evaluation and selection of historical and memorial heritage for registration in the Register of Cultural Property and perpetuation of such heritage sites. Scholars and heritage protection specialists are constantly renewing the debate on the appropriateness of the protection for Lithuanian partisan death sites (where there are no buried remains) and the conditions to be applied to their protection. However, in some exceptional cases and in the face of divergent positions, decisions on the criteria for the evaluation of modern conflict sites, their selection for registration in the Register of Cultural Property and/or commemoration remain pending.

Although the Archaeological Heritage Management Regulation stipulates that archaeological research is obligatory at modern conflict sites, whether listed in the Register of Cultural Property or not, very little archaeological investigation is still carried out. It should be noted that the majority of these investigations consist of the search and exhumation of the remains of German soldiers (funded by the German War Graves Commision (Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e. V.), the remains of soldiers of the Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa) (funded by the Institute of National Remembrance (Instytut Pamięci Narodowej), and the remains of Lithuanian partisans (funded by the Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania (Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimo centras). These investigations are mostly carried out outside the territories of cultural heritage sites, the exhumation of the remains does not result in legal protection to such sites, and the results of the investigations do not affect the adjustment of the accounting data. Archaeological research on the heritage of modern conflicts, which provides data necessary for granting legal protection to cultural heritage sites or for the revision of accounts, is usually carried out on the personal initiative of researchers.

Many modern conflict sites are protected and listed in the Register of Cultural Property on the basis of eyewitness accounts and oral histories. However, there are cases where historical-archival and archaeological research does not corroborate eyewitness accounts. For example, in 2021, in the village of Lazdėnai (Elektrėnai municipality), during the investigation of the graves of Lithuanian and Polish soldiers listed in the Register of Cultural Property, no remains of soldiers were found (Žėkaitė 2022). In 2022, remains were discovered and exhumed in a small hillock located 1.2km away (Oleinik 2023). Archaeological investigations carried out in 2022 at the Veiveriai Skausmas hill (Prienai district), a memorial site of national importance, have not yet confirmed the oral data on the remains of the 82 Lithuanian partisans buried there (Dobeikis 2023)

These case studies are relevant for the revision of accounts of the cultural property i.e. the withdrawal of legal protection in the first case and the revision of the accounts in the second. They also confirm the effectiveness and relevance of integrated (historical-archival and archaeological) research in locating sites of modern conflicts and in assessing, for example, data from the period of Soviet occupation. So far, perhaps the only cultural heritage site where ongoing, state-funded archaeological research is being carried out (also for accounting purposes) is the aforementioned Macikai Nazi German POW camp and Soviet GULAG camp complex (Čičiurkaitė and Kraniauskas 2022b).

In Lithuania, different institutions are responsible for the perpetuation of historical memory, the development of modern conflict sites and heritage policy, and the research and protection of these sites. For this reason, communication between institutions, sharing decisions and research results is essential. However, owing to the different hierarchies of the institutions and the varying legislation governing their activities and accountability, communication on modern conflict site issues is not always timely.

While there is an ongoing debate on whether or not it is necessary to give legal protection to all modern conflict sites and to list them in the Register of Cultural Property, on the other hand, questions are being asked on how to better protect potential modern conflict sites. The problem of the uncontrolled and undocumented exhumation and transfer of the remains of Lithuanian partisans to cemeteries, as well as the excavation and restoration of partisan bunkers and dugouts, has been solved by means of legal regulations and the necessary requirements for these actions. At the same time, the problem of the illegal use of metal detectors at these sites persists.

Another challenge concerns the courtyards of former Soviet security headquarters and their surroundings. As already mentioned, during the period of Soviet occupation, Soviet security headquarters were included in the lists of cultural monuments of Soviet Lithuania for ideological reasons. After the restoration of Lithuanian independence, these buildings were not included in the Register of Cultural Property with the exception of the six sites where Lithuanian partisans are known to have been buried. Historical and archaeological research has confirmed the trend of burial of the remains of Lithuanian partisans and other participants in the resistance to the Soviet occupation regime in the courtyards of the Soviet security headquarters and their surroundings.

The most recent and significant case is the discovery and identification of the remains of Lieutenant Colonel Juozas Vitkus-Kazimieraitis, one of the most prominent Lithuanian partisans, who was the commander of the South Lithuanian partisan area and the organiser of the anti-Soviet and anti-Nazi resistance. He had been buried in the courtyard of the former Soviet NKVD-MVD-MGB (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs - Ministry of Internal Affairs) headquarters in Leipalingis (Kvizikevičius and Zagreckas 2023). Unfortunately, his remains were subsequently disturbed during the construction of engineering communications. This case and the results of previous investigations show that, in order to protect the remains of Lithuanian partisans buried in the surroundings of Soviet security headquarters and to collect all scientific and forensic data about them, it is appropriate to revise the Archaeological Heritage Management Regulation and to oblige the archaeological investigations to be carried out in the courtyards of former Soviet security headquarters before any excavation work is undertaken.

One of the ways to collect information on potential cultural heritage sites is the Inventory of Immovable Cultural Property . The purpose of this inventory is to collect data on potential sites, establish which have valuable properties, and to ensure the publicity and integrity of their data. All persons and institutions may submit data on potential cultural heritage objects to the Inventory of Immovable Cultural Property in accordance with the procedure laid down by law. Although potential objects of cultural heritage are not subject to heritage protection requirements, information about them is recorded and, in the case of a threat, the Department of Cultural Heritage under the Ministry of Culture may initiate the preparation of accounting documents for granting legal protection to such objects.

Protection of immovable cultural heritage also includes its management, knowledge and dissemination. For this reason, the issue of the adaptation of modern conflict sites is relevant and awaits further solutions. Given that most modern conflict sites (with the exception of cemeteries and burials in cemeteries) are located in forests and environments that are otherwise difficult to access, and visually inconspicuous, it is necessary to maintain a balance between public respect and the conservation, management and dissemination of scientific information. In the light of the challenges and issues outlined above, the framework for the protection of the heritage of modern conflicts, some of its processes and requirements, will undoubtedly be subject to change and/or revision. However, the legal regulation of 20th-century conflict sites is not the most difficult challenge. Archaeological research on modern conflict sites and ensuring the need for it will remain the most pressing and greatest challenge in the future.

The spontaneous public search for the remains of Lithuanian partisans, which began in 1988 during the Lithuanian National Revival and continued after the restoration of independence in 1990, prompted the need to establish regulations and procedures for the exhumation and transfer of the remains of victims of 20th-century conflicts and occupation regimes. Government resolutions adopted in 1992 obliged archaeologists to be involved in the exhumation procedure and to carry out the exhumation in accordance with the basic requirements of archaeological research. Owing to the restoration and destruction of authentic partisan bunkers and dugouts, the increase in archaeological investigations at 20th-century conflict sites, as well as the emergence of a distinct field of modern conflict archaeology, the 2022 revision of the Archaeological Heritage Management Regulation stipulated the necessity to carry out archaeological research prior to excavation works at all 19th- and 20th-century conflict sites.

The most extensively investigated sites of modern conflict in Lithuania are the burial sites of Wehrmacht and Polish Armia Krajowa soldiers of the Second World War and Lithuanian anti-Soviet partisans. Partisan bunkers, dugouts, campsites, and battlefields also received considerable attention. The sites of archaeological investigations are mainly determined by commissioned research on the remains of Wehrmacht and Armia Krajowa soldiers and Lithuanian partisans, while the number of excavations carried out for scientific purposes is so far rather small. As of July 2023, 7.3% (n=1764 properties) of all immovable cultural heritage properties listed in the Register of Cultural Property were sites of modern conflict. Of these, 41.4% (n=730 properties) were sites of the Lithuanian Partisan War. The predominance of partisan graves, death and burial sites in the Register of Cultural Property shows that the image of death and sacrifice associated with the Lithuanian Partisan War still dominates Lithuanian heritage protection.

Over the last three decades, modern conflict sites have received a great deal of attention from the public and authorities. A functioning heritage system has been established, heritage accounting has been carried out and the need for archaeological research has been regulated. However, the protection and assessment of 20th-century conflict sites still poses major challenges, the timely resolution of which will determine the future and survival of this important heritage type.

This research was funded by the European Social Fund (project no. 09.3.3-LMT-K-712-23-007) under no. 09.3.3-LMT-K-712, 'Development of Competences of Scientists, other Researchers and Students through Practical Research Activities' measure.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.