Cite this as: Vařeka, P. 2024 Preservation and Heritage Protection of the Archaeological Remains of Prison and Forced Labour Camps from the Period of Nazi Occupation and the Communist Era in West Bohemia, Internet Archaeology 66. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.66.17

Places associated with mass crimes against humanity, which are referred to as campscapes or terrorscapes (cf. van der Laarse 2013; van der Laarse et al. 2014), have left a deep impact on historical memory and have become part of the dark heritage and tangible testimony of our totalitarian past. Contemporary archaeology has an irreplaceable role in dark heritage exploration connected with totalitarian, state-perpetrated repressions and violence of the 20th century (e.g. Haubold-Stolle et al. 2020; Ławrynowicz and Żelazko 2015; Mik and Węglińska 2019; Sturdy-Colls 2015; Symonds and Vařeka 2020; Theune 2018). In Czechia, Nazi and communist prison and forced labour camps have been the subject of historical research for several decades (e.g. Bártík 2009; Borák-Janák 1996; Bubeníčková et al. 1969; Bursík 2009; Kaplan 1992; Padevět 2018; 2019; Petrášová 1994); however, their location, size and internal structures are often unknown. Some of these sites are commemorated by memorials of different kinds, but the exact places where they were situated have usually been forgotten. In addition, attention has not been paid regarding whether any material remains of camps have been preserved in the terrain, which could shed light on their appearance, the living conditions of inmates and consequently the circumstances of heritage protection.

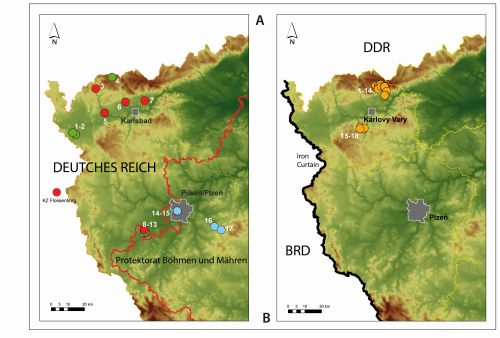

In October 1938, large border regions of Czechoslovakia (Sudetenland) were annexed by Nazi Germany, and since 15 March 1939, the remaining territory was occupied as the so-called 'Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia' (e.g. Gebhardt and Kuklík 2006, 167-92; Klimek 2002, 651-74). In the annexed part of West Bohemia (the entire contemporary Karlovy Vary region and about half of the Pilsen region), the same types of camps were established as elsewhere in Nazi Germany: concentration subcamps, short-term internment camps for Jews, POW camps and various labour camps (Adam 2016; Bružeňák 2015; Bubeníčková et al. 1969, 197, 226-57, 282-388; Laštovka 1971). The survey presented here focused on all sites representing concentration subcamps and a small sample of other types of camps, the total number of which may have reached a minimum of two hundred (Bubeníčková et al. 1969, 437-45). Several forced labour camps were also established in the territory of the Protectorate in the eastern section of the contemporary Pilsen region (Burzová et al. 2013, 67-68; Cironis 1995; Jindřich 1999; Toušek et al. 2014, 51-52), all of which have been studied during the research.

In the post-war period, some camps were used for the internment of Sudeten Germans or other civilians of German origin before their deportation from Czechoslovakia; detained Nazi officials and SS units were also placed here (for deportation of Germans from Czechoslovakia, see Brandes 2000; Staněk 1991; 1996). In the areas of uranium mining, which started shortly after the war under the supervision of Soviet experts, camps for German prisoners of war were also established in West Bohemia (Dvořák 2018, 147; Zeman and Karlsch 2020, 161). However, the most intensive post-war development of the prison camp system according to the Soviet model was closely associated with the communist government at the end of the 1940s and during the 1950s.

After the communist coup in February 1948, repressions against all real or simply potential opponents of the new regime resulted in a rapidly increasing number of political prisoners who were convicted for 'anti-state' activities according to the newly adopted Act No. 231/1948 Coll. on the Protection of the People's Republic. Along with those who were imprisoned for criminal offences and Czech Nazi collaborators, political prisoners were sent to newly established penal labour camps. In addition, according to Act No. 247/1948 Coll. on Forced Labour Camps, any Czechoslovak citizen between the ages of 18 and 60 could be sent without a proper trial for a period of up to two years to a forced labour camp for 're-education' (e.g. Bártík 2009, 15-58; 2017; Borák and Janák 1996; Bursík 2009, 30-34; Dvořák 2018; Kaplan 1992; Petrášová 1994, 337-40). Regarding the communist prison camps, our focus in this study is on penal and forced labour camps associated with the uranium industry, which operated in West Bohemia in 1949-1961.

The research aimed at retrieving, analysing and interpreting material evidence on World War II (WWII) and post-war communist-period prison, forced and compulsory labour camps, which should be considered not only historical but also archaeological sites. Focus on the Pilsen and Karlovy Vary Regions provided a sample of 17 camps from WW II and 18 camps from 1949-1961 in terms of the preservation of archaeological remains, contemporary use and the heritage protection of these sites, which are associated with mass repression and crimes against humanity committed by the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century (Figure 1).

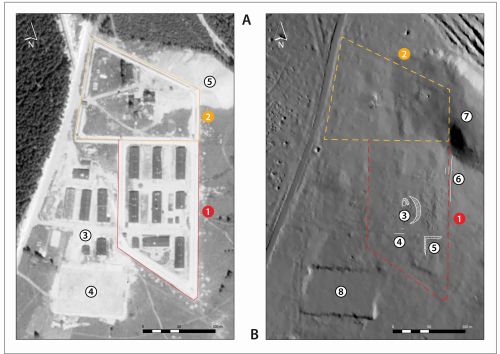

Camps known from historical evidence were located with the use of archival high-resolution aerial photographs, which were projected onto contemporary maps (e.g. Cowley and Stichelbaut 2012; Hanson and Oltean 2013; Pavelková and Netopil 2007; Šafář and Tlapáková 2016). Aerial reconnaissance photographs taken by the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) make it possible to identify the Nazi camps on the studied territory at the end of the war (US Air Force Historical Research Center). The Czechoslovak Army organised aerial photography for the purposes of mapping both the pre-WWII and post-war period (Klusoň and Vítek 2018). Aerial images of West Bohemia from 1946 up to the early 1950s captured the clearly visible remains of already dismantled or demolished prison and labour camps from the occupation period, but in some cases also existing camps with completely preserved structures that were used in the post-war period. The same method was also used to locate the forced and penal labour camps established after 1948. The territory of Jáchymov and Horní Slavkov, where thousands of prisoners were put to work in uranium mines and ore-processing facilities, was photographed by the Czechoslovak Air Force in 1952 and again in 1956 i.e. during the existence of the camp system (Vojenský geografický a hydrometeorologický úřad).

All camp sites have been studied with the use of remote-sensing (aerial photographs by drone and LiDAR) and visual surface survey. A topographic survey was undertaken on sites with well-preserved surface remains such as relief formations, the foundations of buildings or construction debris. A geophysical survey was carried out only on a limited number of sites with suitable conditions (open areas without building structures or vegetation). Small-scale excavations were performed at five sites. In addition, the heritage protection of these sites has been examined, along with the current state of different types of memorial commemorating the former camps.

Five KZ Flossenbürg subcamps were established in the territory of West Bohemia that had been annexed by Nazi Germany in 1943-1944 (Table 1): Holýšov (Holleischen), Kraslice (Graslitz), Ostrov (Schlakenwerth), Nová Role (Neuhrohlau; originally the KZ Ravensbrück subcamp) and Svatava (Zwodau; Figure 1A). In addition, smaller groups of prisoners (Arbeitskommando) were placed in several other sites that have not yet been studied (e.g. Božičany/Poschetzau and Korunní/Krondorf-Sauerbrunn). With the exception of Ostrov, these were female prison camps; however, at the end of the war, male sections were also established in two cases (Holýšov and Svatava). The number of prisoners, who came from many occupied European countries as well as from Germany, ranged from several hundreds to more than one thousand in individual camps (Adam 2016; Bubeníčková et al. 1969, 91-134).

| Site | Region | Type of camp | Date | Description | Area (m²) | Current state | Archaeological research (excluding aerial survey and LiDAR) | Identified archaeological situations | Memorial | Listed heritage site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holýšov-Nový Dvůr (Holleischen-Neuhof) | Plzeň | concentration camp (KZ Flossenbürg sub-camp) | 1944-1945 | baroque and classicist manor farm | 5000m² (female prisoners' section) 2600m² (male section) | post-war and contemporary reconstruction; preserved (inaccessible) | building archaeology survey | no identified remains of the camp; preserved anti-air raid shelter outside the camp | memorial plaque | memorial plaque |

| Holýšov (Holleischen) | Plzeň | POW camp 1 (French, later Italian) | 1940-1945 | barrack camp | 9400m² | field, partly overbuilt | geophysical survey | well-preserved sub-surface remains (c. 90% of the camp area) | memorial stone | - |

| Holýšov (Holleischen) | Plzeň | POW camp 2 (Soviet, later French and Soviet) | 1940-1945 | barrack camp | 9950m² | Woodland, c. two-thirds damaged by water-reservoirs and earthworks | topographic survey and small-scale excavations | remains of at least one brick-built utility building (surface and subsurface remains) | memorial stone | - |

| Holýšov (Holleischen) | Plzeň | labour camp (Deutsche Arbeitsfront Lager) | 1940-1945 | barrack camp | 13,360m² | built-up area | - | - | memorial stone | - |

| Holýšov (Holleischen) | Plzeň | labour camp (RADwJ - Deutches Mädchenlager) | 1940-1945 | barrack camp | 12,200m² | brownfield (inaccessible) | - | - | memorial stone | - |

| Holýšov (Holleischen) | Plzeň | forced labour camp (Tschechisches Frauenlager) | 1941-1945 | barrack camp | 17,400m² | built-up area | - | - | memorial stone | - |

| Cheb (Eger) | Karlovy Vary | POW camp 1 (Soviet) | ?-1945 | barrack camp | 27,670m² | built-up area | - | - | - | - |

| Cheb (Eger) | Karlovy Vary | POW camp 2 (French) | ?-1945 | barrack camp | 15,500m² | Built-up area | - | - | - | - |

| Kolvín | Plzeň | labour-educational camp (Arbeits-enziehungslager) | 1942-1944 | barrack camp | ? | military area (shooting range) | - | - | - | - |

| Kraslice (Graslitz) | Karlovy Vary | concentration camp (KZ Flossenbürg subcamp) | 1944-1945 | factory | ? | factory | - | - | memorial plaque | - |

| Mirošov | Plzeň | labour-educational camp (Arbeits-enziehungslager) | 1941-1945 | barrack camp | 21,430m² | built-up area | - | - | memorial stone | - |

| Nová Role (Neu Rohlau) | Karlovy Vary | concentration camp | (KZ Flossenbürg sub-camp) | 1942-1945 | barrack camp | 14,250m² municipal and industrial waste landfill | - | - | memorial stone | - |

| Ostrov (Schlacken-werth) | Karlovy Vary | concentration camp (KZ Flossenbürg sub-camp) | 1943-1945 | chateaux | ? | chateaux (municipal office) | - | - | memorial plaque | chateaux complex |

| Plzeň-Karlov I | Plzeň | labour-educational camp (Arbeits-enziehungslager) for women | 1943-1945 | barrack camp | 65,870m² | built-up area (c. 90%); scrub vegetation | - | - | - | - |

| Plzeň-Karlov II | Plzeň | labour-educational camp (Arbeits-enziehungslager) for man | 1945 | barrack camp | 9000m² | Škoda Works (inaccessible) | - | - | - | - |

| Rolava (Sauersack) | Karlovy Vary | POW camp (French and Soviet) | 1941-1945 | barrack camp | 21,000m² | woodland | topographic survey and small-scale excavations | well-preserved surface and subsurface remains | Information board | - |

| Svatava (Zwodau) | Karlovy Vary | concentration camp (KZ Flossenbürg sub-camp) | 1943-1945 | barrack camp | 18,200m² | kindergarten and other building, park | topographic survey | surface remains | memorial and information board | memorial (12% of the camp area) |

Three camps were placed in existing building complexes (Holýšov camp in a manor farm, Kraslice in a factory and Ostrov in one section of a chateaux) and two camps were newly built as typical wooden prefabricated barracks (Nová Role and Svatava). Camps were established next to industrial enterprises (Luftfahrtgerätewerke, Metallwerke Holleischen GmbH, Porzellanmanufaktur Allach-München and Siemens Luftfahrgerätewerk Hakenfelde; Figure 2) so that prisoners could be put to work in war production as a slave labour force. In two cases, camps were interconnected with factories by barbed-wire corridors through which inmates marched to work and back (Nová Role and Svatava). The Holýšov and Svatava camps were liberated by the Allies at the end of the war. The others were evacuated in April 1945, and the prisoners were driven on Death Marches in various directions. Shortly after the war, the Svatava barracks camp was burnt down owing to concerns about the spread of contagious diseases. Captured SS as well as NSDAP and SA functionaries were interned in the Nová Role camp. In the post-war period, the manor farm in Holýšov was nationalised and became a state farm; the Kraslice factory continued industrial production and the chateaux in Ostrov was turned into a school (Bružeňák 2015; Němec 1985; Valeš and Schröpfer 2017).

All the preserved building complexes that were used as camp facilities were reconstructed without any documentation in the post-war period, permanently removing any possibility of building archaeology research on them. In all cases, commemorative plaques have been placed on the outer walls of the buildings; however, the places where the prisoners were held are not represented. The Holýšov manor farm (female section of the camp) is currently used as a residential and storage complex, and the neighbouring sheepfold (male section of the camp) is being redeveloped into flats and offices (Figure 3). The Kraslice factory is operational (clothing production), and the Ostrov chateaux is used as a municipal office.

The Svatava subcamp (18,200m²) was formed by three large barracks for prisoners plus several other facilities. The SS quarters were placed outside the camp. A memorial was built in the eastern section of the camp in 1956 (listed as a heritage site since 1958). It consists of a sculpture of a female prisoner and stones with the names of the countries of origin of the internees, and also includes the foundations of one of the barracks. It is the only case in West Bohemia where a memorial was created directly in the area of a former camp, covering about 10% of its area. The rest of the camp area has been partly built over by a kindergarten complex and other buildings, but for the most part it is overgrown with vegetation. A unique collection of personal items and artefacts made by female prisoners is kept in the local district museum in Sokolov. The archaeological survey showed that the terrain of the camp was significantly modified in the post-war period (e.g. lowering of the terrain level) although some features have been well preserved. Apart from the concrete foundations of the easternmost barrack, two anti-aircraft shelters formed by underground tunnels made of bricks and a large rectangular water-reservoir have been documented. One of the air-raid shelters is included in the playground of the kindergarten that covers a large part of the former camp (Figures 4-5).

The Nová Role concentration camp (14,250m²) consisted of five large prisoners' barracks, three smaller buildings and an SS headquarters, with quarters for the guards that were situated outside the fenced camp. In contrast to the well-preserved relics of the Svatava camp, the terrain in Nová Role has been completely changed, as it was used for landfill from the 1960s to the 1990s. Comparative analysis of historical aerial photographs, maps and the current 3D terrain model showed that an artificial mound of waste covering the former camp area reaches several metres in height. The huge number of fragments of porcelain vessels found during the surface survey indicates that, among other things, production waste from a nearby porcelain factory was deposited here. The area has recently been reclaimed and is mostly used as pastureland. A memorial stone situated c. 200m away at the nearby railway station commemorates the camp.

A total of 70,000 prisoners of war were registered in Sudetenland in April 1944 (Adam 2018, 169). There were several dozen POW camps in West Bohemia that were mostly under the administration of the main camp Stalag VIIIB Weiden, but there were also hundreds of separate working groups of captives (Bubeníčková et al. 1969, 282-388, 422-36). So far, the survey has focused on a small sample consisting of four sites and the best-preserved POW camp, Rolava (Sauersack), has been studied since 2010 (Figure 1A). The Rolava camp for French and Soviet POWs represents the first site of this kind that has been studied in the Czech Republic using archaeological methods. The camp, with a rectangular plan and regular layout of buildings (total dimensions of 21,000m²), was built in 1941 to provide a labour force to the neighbouring tin ore mining and processing complex. Owing to the location of the site in a remote wooded area on the ridges of the Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge/Krušné hory), the surface traces of the camp have been uniquely preserved. This includes elements such as the concrete foundations of wooden prefabricated buildings, brick structures, and also the remains of sewers, storage cellars and fencing. Test-pitting of the waste area provided material evidence regarding everyday life in the camp and also documented the diametrically different living conditions of French and Soviet prisoners (Hasil et al. 2015; Hasil et al. 2020).

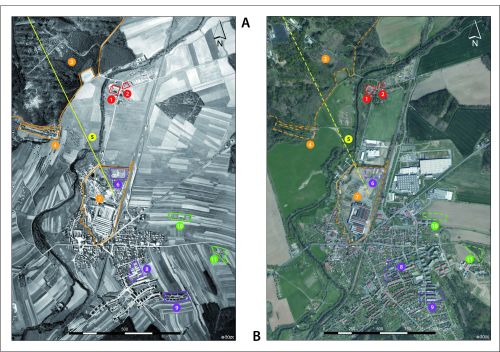

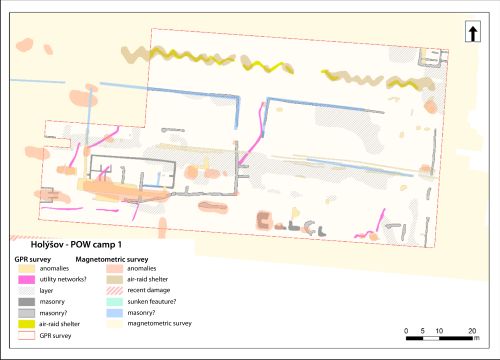

These were not only concentration camp prisoners working in the ammunition factory in the town of Holýšov but also prisoners of war from two camps, the remains of which became the subject of archaeological research. The first French POW camp was established on the north-eastern edge of the town in 1940. They were replaced by Italian POWs, probably in November 1943 (Valeš and Schröpfer 2021, 158-71). The camp, for about 350 prisoners, had a rectangular layout (9450m²) and a smaller annexed section on the western side. There were five large barracks, several smaller buildings in the camp and an air-raid shelter formed by characteristic zigzag trenches that lined its northern side. An aerial photograph from 1946 shows that the camp was dismantled shortly after the war. Today, the site is located on arable land and its western part has recently been built over. A geophysical survey using magnetometry and ground-penetrating radar revealed the well-preserved remains of the camp structures. It was possible to identify the foundations of prison barracks and other buildings, linear features indicating drainage ditches or sewerage, and the air-raid shelter (Figure 6).

The second POW camp was built 200m north-west of the first one. It is assumed to have originally housed Soviet prisoners of war, and from late 1943 on it also served as a French POW camp (Valeš and Schröpfer 2021, 121-34, 181-84). The camp, with an irregular polygonal plan (9950m²) where more than 300 prisoners were kept, had a separate section for Soviet prisoners attached to the north-eastern side. There were three large barracks and about five smaller buildings in the main area, and a single large barracks stood in the separate 'Soviet' section. Air-raid trenches were placed along its north-eastern side. This camp was also demolished shortly after the war and according to oral testimonies, it was later used for training activities of the Czechoslovak People's Army (training fox-holes and dugouts were detected by the survey). Recently, roughly two-thirds of the camp area was totally destroyed due to earthworks and the construction of a cascade of ecological water reservoirs. A topographic survey documented the brick foundations of one building (8mx23m) in the last preserved section of the camp. So far, test-pitting has not produced any evidence of other camp structures but has shown that the place was used in the post-war period for the deposition of municipal waste. Both camps are marked by memorial stones situated several hundred metres away from their actual location. The link between the former ammunition factory (currently an abandoned brownfield) and the forced labour of POWs in the war industry is commemorated by a memorial slab by the factory chimney (which served as an anti-aircraft observation post during the war), where three Italian prisoners were shot on 26 April 1945.

Cheb is another West Bohemian town where prisoners of war were made to work in Nazi war production. Two POW camps were established in the vicinity of the aircraft factory that was built on the south-eastern edge of the town in 1940 (Matějíček 2013, 323-39). Remains of the factory airport with concrete runway, taxiways and other facilities have been preserved and are used by the local air-club. However, the survey has demonstrated that a large industrial complex has recently been built on the very site of the former Soviet POW camp (27,750m²), and a solar power plant has covered the smaller French POW camp (15,500m²) near the airport.

Three sites in Holýšov have been studied as part of the large number of labour camps of various types that were established in the territory of West Bohemia, which had been annexed to the 'Third Reich' (Figure 1A). The German Labour Front (Deutsche Arbeitsfront - DAF) camp, which was formed by ten large prefabricated barracks (13,360m²), was built in the town during the war for about 1000 male workers who were sent to the ammunition factory, mostly from occupied countries. Czech female forced labourers from the 'Protectorate', who were also deployed in the factory ('Totaleinsatz' forced labour), were housed in another camp (Tschechisches Frauenlager; capacity of around 850 persons) consisting of eleven wooden barracks and other facilities (17,400m²). A labour camp for German girls (Deutches Mädchenlager) who were fulfilling their so-called Reich Work Service (Recharbeitsdienst der weiblichen Jugend - RADwJ) was built directly in the factory area (12,200m²). Its location meant that all of its sixteen wooden buildings burned down completely during an American air raid on 26 April 1945, taking the lives of many of the young female inhabitants. After the war, both Deutsche Arbeitsfront Lager and Tschechisches Frauenlager became an internment camp for local Sudeten Germans before they were deported from Czechoslovakia (Valeš and Schröpfer 2021, 44-120, 188-90).

| Site | Region | Type of camp | Date | Description | Area (m²) | Current state | Archaeological research (excluding aerial survey and LiDAR) | Identified archaeological situations | Memorial | Listed heritage site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horní Slavkov - Camp XII | Karlovy Vary | 1951-1954 | barrack camp | 48,610m² | park, sport facilities and playgrounds | surface survey | some surface remains | - | - | |

| Horní Slavkov - Ležnice | Karlovy Vary | 1950-1955 | barrack camp | 41,230m² | woodland | surface survey | surface remains | - | - | |

| Horní Slavkov - Prokop | Karlovy Vary | POW camp, penal labour camp | 1947-1949,1949-1955 | barrack camp | 53,950m² | prison - | - | - | - | - |

| Horní Slavkov - Svatopluk | Karlovy Vary | penal labour camp | 1951-1955 | barrack camp | 24,870m² | industrial cow farm | - | - | - | - |

| Jáchymov -Bratrství | Karlovy Vary | POW camp, penal labour camp | 1946-1949,1950-1954 | barrack camp within a fenced mining area | 5,900m² | summer cottage camp and sport facilities | geophysical survey | subsurface remains | - | camp area and one building of the former mine |

| Jáchymov -Eliáš I | Karlovy Vary | POW camp, penal labour camp | 1946-1949, 1949-1950 | barrack camp | ? | underneath a tailings heap | - | - | - | Mining Region Erzgebir-ge/Kruš-nohoří |

| Jáchymov - Eliáš II | Karlovy Vary | penal labour camp | 1950-1959 | barrack camp | 16,400m² | woodland | topographic survey small-scale excavations | well-preserved surface and subsurface remains | informati-on board, Boy-Scout Cross memorial in the vicinity | Mining Region Erzgebir-ge/Kruš-nohoří |

| Jáchymov - Mariánská I | Karlovy Vary | POW camp, penal labour camp | ?-1949, 1949-? | barrack camp | 17,380m² | pastureland | geophysical survey | subsurface remains | information board in the vicinity | Mining Region Erzgebir-ge/Kruš-nohoří |

| Jáchymov - Mariánská II | Karlovy Vary | penal labour camp | ?-1960 | barrack camp | 25,850m² | home for the elderly and persons with disabilities; partly meadow and hedges | - | - | information board in the vicinity | Mining Region Erzgebir-ge/Kruš-nohoří |

| Jáchymov - Nikolaj | Karlovy Vary | forced labour camp, penal labour camp | 1950-1951, 1951-1958 | barrack camp | 18,000m² | woodland, partly open area | geophysical survey small-scale excavations | well-preserved surface and subsurface remains | information board | Mining Region Erzgebir-ge/Kruš-nohoří |

| Jáchymov - Rovnost I | Karlovy Vary | POW camp, penal labour camp | 1946-1949, 1949-1950 | barrack camp | ? | underneath a tailings heap (exact location unknown) | - | - | - | Mining Region Erzgebir-ge/Kruš-nohoří |

| Jáchymov - Rovnost II | Karlovy Vary | penal labour camp | 1950-1961 | barrack camp | 22,800m² | weekend cottages, hotel complex | - | - | information board | Mining Region Erzgebir-ge/Kruš-nohoří |

| Jáchymov - Svornost | Karlovy Vary | POW camp, penal labour camp | ?-1949, 1949-1954 | barrack camp | 7880m² | gradually overgrowing area | - | so-called 'bunker' (correctional facility within the camp) | information board; reconstruction of part of the fencing and stairs leading to the mine which is open to the public | Mining Region Erzgebir-ge/Kruš-nohoří |

| Jáchymov - Ústřední | Karlovy Vary | POW camp, penal labour camp | 1947-1949, 1950-1954 | barrack camp | 13,790m² | pastureland and woodland | geophysical survey | preserved subsurface remains | - | - |

| Jáchymov - Vršek | Karlovy Vary | POW camp, forced labour camp, penal labour camp | 1946-1948, 1949-1951, 1951-1957 | barrack camp | 11,300m² | overgrown with vegetation, partly open areas and recreation facilities | topographic survey | preserved terraces of former camp buildings | - | camp area |

| Plavno | Karlovy Vary | forced labour camp | 1949-1951 | barrack camp | 22,250m² | woodland | topographic survey | preserved surface remains | - | - |

| Vykmanov I | Karlovy Vary | penal labour camp | 1954-? | barrack camp | 20,000m² | prison | - | - | - | - |

| Vykmanov II | Karlovy Vary | penal labour camp | 1951-1956 | barrack camp | 9870m² | brownfield | - | - | - | Neighbouring uranium ore-processing plant ('Red Tower of Death') |

The camps in the city were completely overbuilt by modern housing in the 1970s-1990s, and the area of the Deutches Mädchenlager is located within the abandoned factory, which is inaccessible. Thanks to the effort of the town museum, the places of all the camps have been marked with memorial stones in the last few years.

Three 're-educational' forced labour camps (Arbeitserziehungslager) were established in West Bohemia on the territory of the Protectorate for the Czechs who were accused, for example, of offences against labour discipline or for avoiding forced labour in Germany (Bubeníčková et al. 1969, 197-99). The Kolvín and Mirošov (21,430m², 16 barracks) camps for a total of 3000-4000 prisoners (Kolvín probably also housed women) were located in the Rokycany district from the beginning of the 1940s. Forced labour mostly meant working in the forest, logging trees and wood processing in sawmills in the Wehrmacht military training area (Truppenübungsplatz Kammwald). In April 1945, internees from the evacuated Gestapo prison in Brno, Moravia, were also placed in the Mirošov camp (Cironis 1995; Jindřich 1999). The site of the Kolvín camp is still located in a restricted military area, which is currently used by the Czech Army and is inaccessible. After the war, Mirošov became an internment camp for Czech Germans destined for expulsion from the country and, from 1948 it served as a centre for elderly persons of German origin who could not be included in transports to Germany. Later, it began to be used as a Social Care Complex. The area is currently completely overbuilt by a retirement home, and the former camp is commemorated by a memorial stone.

Another 're-educational' forced labour camp was established at the southern edge of the Škoda Works in Plzeň-Karlov, which served as a huge armoury for Nazi Germany during the Second World War. The first camp for girls and women aged 15 to 55 (capacity c. 400 persons; 65,870m²) was built in 1943 and, in early 1945, it was supplemented by a smaller camp for male forced labourers (9000m²). Both camps emptied on 25 April 1945 when internees managed to escape during a devastating USAAF air raid on the Škoda factory. These camps were used for the internment of civilians of German origin from Pilsen and surrounding areas after the war (Burzová et al. 2013, 67-68; Toušek et al. 2014, 51-52). Almost the entire area of the women's prison camp has been recently redeveloped with industrial and commercial facilities (including a Lidl supermarket in 2022). The site of the male prisoners' camp is located in an open area of the Škoda industrial complex, and preservation of its potential sub-surface remains could not yet be carried out owing to restricted access.

It was the uranium from the Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge/Krušné hory) that allowed Stalin's regime to begin the rapid development of nuclear weapons in the post-war period, culminating in 1949 in the first successful test of the Soviet atomic bomb, which threatened the military superiority of the United States at the start of the Cold War (Bursík 2009, 26-29; Zeman and Karlsch 2020, 41-48, 151-58). According to the Soviet model, an unfree labour force was used on a mass scale for mining and processing uranium ore in Czechoslovakia, and POW, forced labour and prison camps grew up near the uranium mines in the area of the historical mining towns of Jáchymov (Joachimsthal) and Horní Slavkov (Schlaggenwald) in West Bohemia (Figure 1B). On a much smaller scale, uranium ore deposits were already being extracted in Jáchymov during World War II by Nazi Germany with the use of prisoners of war. One POW camp for French and later for Soviet captives was established near the Shaft Werner (Adam 2018, 169; Bártík 2017, 7-10). After the war, the Soviets began sending German POWs to work in West Bohemian uranium shafts from 1946 on (Bártík 2017, 10-13). Following the agreement by the Allied powers, German captives were released by the end of 1948 (some left the camps in 1949) and were immediately superseded by Czechoslovak convicts, including thousands of political prisoners sentenced in many cases to more than 10 years or even life sentences. As slave labourers, they were forced to extract strategic uranium ore in appalling conditions and pushed to the very limit of their physical capabilities (Bártík 2009; 2017; Bursík 2009; Petrášová 1994; 2002).

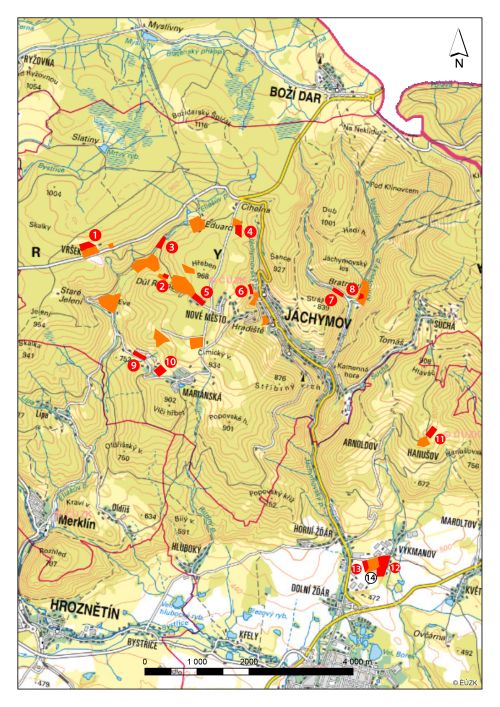

There were probably seven camps for German prisoners of war linked to uranium mines around Jáchymov in 1946-1948 (Eliáš I, Mariánská I, Rovnost I, Ústřední and Vršek), all of which later housed Czechoslovak prisoners (Bártík 2017, 10-13). In 1949-1950, three forced labour camps were set up in this area; however, inmates sentenced to a maximum of two years of 're-education' by hard labour did not represent suitable workers for uranium mining (Bártík 2009, 101-4; 2017, 13-17). Two of these camps were therefore transformed into penal labour camps (Nikolaj and Vršek), and the third was closed (Plavno) by 1951. A total of 14 penal labour camps were established in the former district of Jáchymov in 1949-1951 (later renamed correctional labour camps), mostly around the town on a territory of c. 25km² (Bártík 2017, 34-65; Figure 7). Owing to dynamic mining activity, two camps were abandoned and covered by heaps of waste rock in 1949 (Eliáš I and Rovnost I), and the third was dissolved for unclear reasons (Mariánská I). All these camps were soon superseded by new facilities (Eliáš II, Mariánská II and Rovnost II). According to aerial photographs, the area of the camps ranged from 0.5 to 2.5 ha, but they were mostly 1-2 ha and housed 300-1500 prisoners. The camps were not built according to a uniform plan and differed from case to case (rectangular, trapezoid, pentagonal or polygonal plan, with various internal arrangements), as did the number of buildings (usually 10-20). Aerial photos show the close spatial link between camps and mining areas, which in some cases were interconnected by fenced corridors. Uranium ore-processing facilities were also situated in close proximity to the camps (Figure 7).

As a result of the depletion of ore deposits, the mines and adjacent prison camps were gradually closed during 1954-1961 and in most cases systematically razed to the ground (Bursík 2009, 159-64). From the former mining and processing complexes, brick buildings have been preserved in three locations (Eliáš: compressor station; Rovnost: the so-called cáchovna/Zachenhaus, where the prisoner miners were registered before going down the pit; Vykmanov: the so-called 'Red Tower of Death', representing a component of the uranium ore processing facility). The subsequent use of the former camp areas is a key factor in the preservation of their material remains. In six cases, the area has been preserved without significant interventions as pastureland (Mariánská I and Ústřední) or is partly or completely overgrown with trees and bushes (Eliáš II, Nikolaj, Plavno and Svornost). Two camps are buried under spoil tips (Eliáš I and Rovnost I, see above), and three were built on to become a recreational facility (Bratrství as a summer cabin camp; Rovnost for weekend cottages and a hotel complex) or a home for the elderly and persons with disabilities (Mariánská II). In two cases, the camp facilities were later used and rebuilt (Vršek - Czechoslovak People's Army base; Vykmanov II - Škoda Trolleybus Factory; in both cases recently demolished). The Vykmanov I camp has retained its function and is still used as a prison.

The remains of the camps in non-overbuilt areas have been preserved in the form of relief formations, represented mostly by foundations, building debris, sewage systems and fencing (best preserved in wooded areas; Figure 8). Subsurface remains were detected by geophysical survey in open areas of two camp sites. A comparison of aerial photographs from 1952 and 1956 and a digital terrain model make it possible to identify relief traces of massive uranium mining formed by 'tailings' heaps, but also other components of mining and processing areas. Their spatial delimitation demonstrates the extraordinary scale of interventions in the landscape, which is manifested by the drastic transformation of the original terrain.

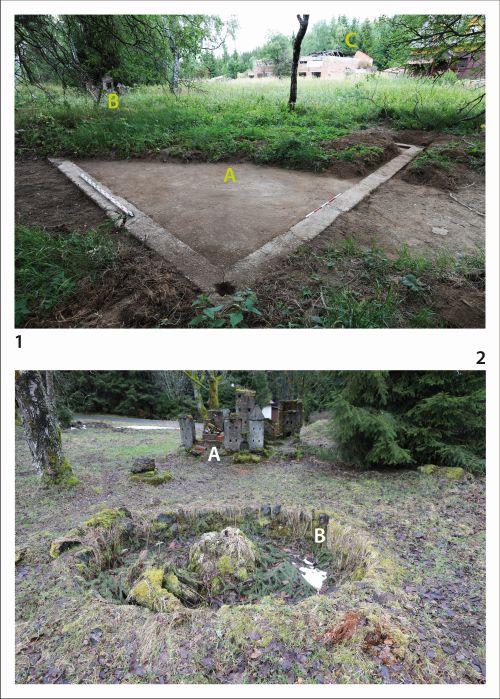

Trial excavations of two camps have produced detailed information about their construction, everyday life in the detention facility, and also the ways in which the camps were demolished. Foundations of prefabricated wooden prisoners' barracks were revealed, including construction details of their upper structure and installations and the remains of brick buildings (e.g. washroom, kitchen, storage cellar) and other features (fencing, watch tower or drainage and sewage system; Figure 9). Fragments of clothing and footwear have been found in archaeological contexts, as well as prisoners' lost or discarded personal items, such as hygiene items or medicine packaging. The uncompromising security is documented by fired cartridges found in the fence restricted zone. Rescue research in the area of the former mine near the Rovnost II camp uncovered the foundations of a canteen for civilian employees with an adjacent waste area, which contained a large concentration of broken dishes and bottles of alcohol. A well-preserved brick-built model of a medieval castle (diameter c. 1.5m) placed near a little pool with a fountain could have had an ornamental function in front of the canteen, which, according to oral tradition, may have been built by the prisoners on the orders of the local camp commander (Interview 1 and 2; Figure 10).

The communist regime wanted places associated with the mass repressions, violation of human rights and judicial crimes of the late 1940s and 1950s to be forgotten. Sites of former prison camps from the period of communist totality could thus be commemorated by former political prisoners and the public only after the Velvet Revolution in 1989. The Red Tower of Death in Vykmanov represented the first component of the 'uranium Gulag' as it was called by former political prisoners and was declared a cultural monument in 1997 (Figure 11). It became a symbol of the suffering of prisoners in the uranium mines. The brick building is formed by a tower with seven storeys in which uranium ore was crushed and sorted and an adjacent ground-floor hall, which was used as a warehouse for ore. From there, barrels filled with ore were loaded onto trains via a nearby railway that transported the strategic cargo directly from this site to the Soviet Union. The processing plant was operated by political prisoners who were not provided with any protective equipment. In 2008, this material proof of the communist regime's repression became a national cultural monument. In 2017, part of the cadastral territory of Jáchymov was listed a landscape cultural zone (Mining Cultural Landscape), which also includes the territory of several prison camps (Eliáš, Nikolaj, Rovnost and Svornost; some other camps outside the zone also became listed sites: Bratrství, Mariánská I and Vršek). In 2019, the entire area was placed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as the Erzgebirge/Krušnohoří Mining Region, which also includes the Vykmanov plant (https://geoportal.npu.cz; https://www.pamatkovykatalog.cz). Currently, the 8.5km-long 'Jáchymov Hell' educational trail, which was established by a civic organisation, presents the sites of some of the former uranium mines and also four camps (Eliáš, Nikolaj, Rovnost and Svornost) in the areas surrounding Jáchymov.

The first camp for German POWs who worked in the uranium mines was established in Horní Slavkov (25km south-west of Jáchymov) in 1946 (Bártík 2017, 10). After the Germans were released in 1948-1949, Czechoslovak prisoners began to arrive, and a total of four camps were placed around the town covering an area of c. 12km² (Camp XII, Ležnice, Prokop and Svatopluk; Bártík 2017, 66-76; Tomíček 2000, 221-35; Figure 12). Compared to Jáchymov, the camps in Horní Slavkov were larger, housing 1050-2500 prisoners, with an area ranging from 2.5 ha to 5.4 ha. Just as in Jáchymov, the camps were attached to individual shafts and in two cases also via barbed-wire corridors. The camps of rectangular, rhombus or pentagonal plans ranged from ten to over twenty buildings, which formed irregular built-up internal structures. The uranium shafts along with the adjacent camps were closed for the same reasons as in Jáchymov in 1954-1955.

The largest camp has been used as a prison ever since (Prokop), and the other three have been demolished. A large industrial cattle farm was built in the area of one camp (Svatopluk), another one is overgrown with trees (Ležnice), and the area of the last one has recently been adapted into a town park with playgrounds for children and a ski slope with a lift (Camp XII; Figure 13). Highly visible surface remains have been documented in Ležnice, and some seem to have been preserved also in Camp XII despite massive terrain works. The Horní Slavkov camps are not marked by any memorial stones or information panels. A symbolic grave for political prisoners is located in the parish cemetery near the St George Church in the town centre. Not a single component of the Horní Slavkov prison camp complex is listed as a heritage monument.

With the use of historical evidence and aerial photographs, a total of 17 camp sites were located in West Bohemia from the period of Nazi occupation, 13 of which were situated on the territory annexed to Germany (Sudetenland) and 4 on the territory of the so-called Protectorate. In addition to the 5 subcamps of the Flossenbürg concentration camp in the Sudetenland and 4 forced labour camps in the Protectorate, all other sites represent only a sample of a much larger number of various camp types that were set up from 1939 to 1945 in the study area. A field survey of the camp sites has revealed the state of preservation of the material remains and the current use of former camp areas.

From the two concentration subcamps that were established in the previously unbuilt areas, some surface remains and very likely also subsurface archaeological remains have been preserved in one case (Svatava), while the other camp site is buried under landfill (Nová Role). Building complexes into which three subcamps had been placed have been preserved in their entirety; however, post-war reconstructions seem to have erased the traces of their use as detention sites during the war (Holýšov-Nový Dvůr, Kraslice and Ostrov). The contemporary use of former concentration camp areas shows a very utilitarian approach to these sites, which are directly linked to the dark heritage of Nazi terror. Their uses today include a municipal office, commercial and residential complex, kindergarten, industrial enterprise and a pastureland placed on a re-cultivated landfill. Regarding other types of camps, only a few places situated outside built-up areas have been at least partly preserved as intact archaeological sites. The unique remains of the Rolava POW camp have been archaeologically studied recently, as well as the material traces of two POW camps in Holýšov. Other POW, forced and compulsory labour camp sites show the devastating impact of recent construction activities directly on the areas of former WWII camps, with no attention being paid on behalf of heritage institutions (Holýšov, Cheb, Mirošov and Plzeň-Karlov). Some camp sites are situated in currently inaccessible unbuilt areas and the preservation of some material remains cannot be excluded (Holýšov, Kolvín and Plzeň-Karlov II).

All concentration camps and one 're-educational' forced labour camp (Mirošov) have been marked with commemorative slabs, stones or a monument and have become objects of respect, remembrance and piety in the post-war period. Surprisingly, no attention was paid to the actual camp areas and preserved material features. Post-war commemoration and the formation of historical memory were mostly based on the testimonies of former prisoners, resistance members and Red Army liberators (the liberation of West Bohemia by the United States Army was not mentioned during the communist regime), as well as archival sources. With the exception of Svatava, where a monument was established in one section of the demolished concentration camp, the authentic material remains were replaced by memorials. The architecture in which three concentration camps were established was adapted for new utilitarian functions without any limitations. This approach is characterised succinctly in the registration sheet of the Holýšov-Nový Dvůr concentration camp heritage site from 1958:

'Koncentrační tábor z let 1943-1944 byl umístěn v celém hospodářském dvoře čp. 33 … . Dnes jsou tyto budovy využívány jako normální hospodářské budovy státního statku, památka na koncentrační tábor je symbolizována tím, že zeď vpravo od vchodu do hospodářského dvora je opatřena ostnatým drátem a na této zdi na straně k silnici je veliká asi 110 cm vysoká a 190 cm široká pamětní deska černé barvy s bílým písmem … .'

(The concentration camp from 1943-1944 was located on the entire manor farm No. 33 … . Today, these buildings are used as normal outbuildings of the state farm, and the concentration camp is symbolically commemorated by the wall to the right of the entrance to the farm yard equipped with barbed wire; there is a 110cm high and 190cm wide metal plaque on this wall on the side facing the road with white lettering …') https://www.pamatkovykatalog.cz

It is this plaque, not the original camp, that has become the object of heritage protection (the barbed wire which is mentioned in the registration sheet has disappeared). This is why the sheepfold where male prisoners were housed is currently and legally being rebuilt into a residential and office building. In Svatava, the memorial, which is a listed heritage site, covers only c. 10% of the camp area, while a kindergarten was built on its much larger area, and its playground is situated on the very same site as the former camp's Appelplatz (roll-call yard).

With the exception of the Mirošov 're-educational' forced labour camp site, places of forced, compulsory labour and POW camps are not marked by any memorial plaques or stones, and their location has been forgotten in the post-war period. Recent interest in these WWII sites can only be seen in Holýšov, where the local museum has organised the establishment of memorial stones that mark the approximate location of all five labour and POW camps on its cadastral territory. The findings that intense construction activities at a number of former forced labour and POW camp sites were carried out in recent years without any rescue archaeological research is alarming. This seems to indicate an ignorance concerning WWII archaeology sites in heritage practice and may also reflect the fact that contemporary archaeology has not yet become an integral component of this field.

The survey, which focused on the communist period, located all 18 forced and penal labour camps linked to uranium mines in West Bohemia from 1949 to 1961, some of which were used as POW camps for German captives from 1946 to 1948/1949, and several may have originated during WWII as POW camps for Allied soldiers. Due to their location in distant places, especially in Jáchymov, more than half of the camp sites have been preserved in woodland or pastureland. Both non-invasive research and test-pitting demonstrated that well-preserved archaeological remains can provide valuable evidence regarding the materiality of the communist campscape. As for the other camp sites, long-term continuity in their use can be seen (a contemporary prison), as well as conversion into industrial or agriculture enterprises. The rapid transformation of the Jáchymov landscape of mass repressions into a mountain resort of mass recreation since the 1960s is reflected in the reuse of some camps for summer camping, weekend cottages, a hotel and areas for various sports activities, as well as one large social facility. Similar use can also be found in one case in Horní Slavkov, where the whole area of one camp has been recently adapted into a town park with facilities for children's games and sports.

After a long period of official silence about these sites of mass repressions by the communist regime, interest in the former prison camps only began to appear in the 1990s. In West Bohemia, attention was focused on the Jáchymov area, which had the highest number of forced and penal labour camps, while Horní Slavkov went unnoticed. Currently, an educational trail is available to tourists at several camp sites around Jáchymov, which are marked by information boards. The first heritage site linked to the 'uranium gulag' was inscribed on the National Heritage List of cultural monuments in 1998. The intention to protect the unique historical mining landscape of the Ore Mountains resulted in the addition of the region to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2019. The demarcated heritage zone also covers four communist camp sites. In addition, four more uranium-mining, processing and camp sites from the same period situated outside the zone are currently also listed as heritage sites. Other Jáchymov prison camp sites from the late 1940s and 1950s and all Horní Slavkov camps lack any heritage protection. The changing approach to the materiality of dark communist heritage is reflected in the activities of civic organisations and local museums, which are aiming to make some sites with authentic material remains accessible to the public.

The survey of various types of forced labour and prison camps from the period of the Nazi occupation and the communist regime in West Bohemia represents the first attempt to examine a representative sample from one larger area of the material remains of archaeological sites that are associated with the dark heritage of the 20th century in Czech lands. Both non-invasive research and test-pitting have demonstrated that the remains of former camps sites that have not been built on are usually well preserved below ground level and in some cases also still possess visible surface features. The archaeological record shows similar attributes owing to the same character of the camps' construction and the process of removing camp facilities after they ceased to serve their function. The predominantly prefabricated wooden barracks were stripped down to their foundations, and brick-built utility barracks (sometimes equipped with basements) were also demolished. In addition to building remains, mostly drainage ditches, utility lines and traces of various installations and fencing can also be found. The physical space of both the Nazi and communist camps reflect their purpose of confining and providing basic shelter with only rudimentary sanitation available to those who were considered economic resources and an expendable slave labour force.

As in other parts of Nazi Germany and occupied Europe, the system of camps in West Bohemia was interconnected with war armament production, which relied heavily on the forced labour of foreign civilians, prisoners of war and concentration camp inmates. The post-war communist regime in Czechoslovakia also soon paired unfree labour with massive armaments at the beginning of the Cold War, which were linked to the hasty extraction of uranium needed for the development and production of Soviet nuclear weapons.

The research has documented the ambivalent post-war attitude towards concentration camp sites, which on the one hand expresses a deep respect for sites where Nazi victims suffered and died and is represented by the establishment of memorial sites, but on the other hand shows a lack of interest in the actual sites of the former camps themselves. The authentic material remains were usually ignored and substituted by memorials that became symbols of the struggle against Nazism. This attitude at present still remains the same. As for the labour and prisoner-of-war camps, they have never become memorial sites (with only a few exceptions) and are not embedded in the area's local historical memory. Some of the communist forced and penal labour camps from 1949-1961 have only recently become the subject of remembrance, and these places still represent a contested past in the Czech Republic.

In recent years, the archaeology of the dark heritage of the 20th century has demonstrated its potential to make a significant contribution to the research on the nature of totalitarian regimes through the hitherto neglected tangible evidence of mass repression and crimes against humanity. At the same time, archaeology provides key data on the preservation and heritage protection of sites that form an irreplaceable material component of modern historical memory, despite the fact that they are not represented by clearly visible and easily presentable material traces in the field.

This study was funded by the Czech Science Foundation (GAČR), project No. 22-43070L Bioarcheology and Landscape Archaeology of the Nationalist-Socialist Repressions: Central-Eastern European Perspective.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.