Cite this as: Keller, C. 2024 Between Craft and Industry: Archaeological research on Rhenish pottery production of the late 18th to early 20th century, Internet Archaeology 66. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.66.8

Pottery production in Germany was always an important craft, supplying everyday utensils for kitchen and table. It has shown extremely contradictory developments since the late 18th century. On the one hand, a strong insistence on traditional production techniques and forms can be observed until the early 20th century. Karl Kolbach describes a stoneware potter in Lüftelberg near Bonn, who talks about the tradition of his craft:

'Mir maache he de Pött noch gerade su, wie se och de aal Römer he gemaat han' (We make pots here just the way the old Romans did) (Kolbach 1908, 28).

On the other hand, ceramics production was one of the first economic sectors to show the initial signs of industrial production as early as the 18th century. The process started with the foundation of the Königlich-Polnische und Kurfürstlich-Sächsische Porzellanmanufaktur at Meißen in 1710 and the establishment of the Etruria factory by Josiah Wedgwood in 1769 (König and Krabath 2012, 152-53; Kybalová 1990, 25-34). In the beginning, pottery from these manufacturers was an expensive commodity made for upper-class households, but this changed during the course of the 19th century when mass-produced creamwares and porcelain coming from factories around Europe flooded the markets.

Archaeologically, these changes in pottery production, which were triggered and intensified by industrialisation, can be particularly well studied. This is due, on the one hand, to the large number of companies involved. On the other hand, and much more significant from an archaeological point of view, is the fact that, especially in the context of ceramics production, semi-finished and finished products are found in large numbers in or close to the place of production, since recycling of misfired products is impossible and ceramics are permanently preserved in the archaeological record.

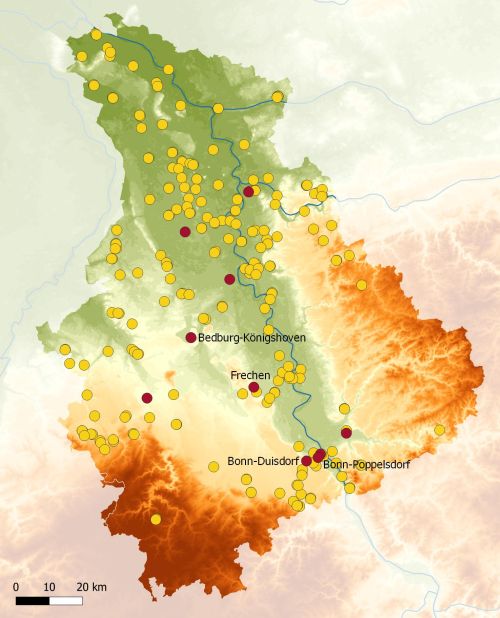

In the Rhineland, the western part of Germany's state of North Rhine-Westphalia and the area of responsibility of the archaeological state service LVR-Amt für Bodendenkmalpflege im Rheinland (where there is a rich heritage of pottery production sites from the early medieval period onwards), some sites of the modern era have been excavated in recent years (Figure 1). These can be used as case studies to illustrate this contrast between continuity and change.

Interest in the late medieval and post-medieval stoneware production in Frechen had already started during the 19th century. The highly decorated vessels in particular, produced during the course of the 16th century, were of interest for collectors and museums (Solon 1892, 13-24). From the 1950s, local historians (namely the city archivist Karl Göbels) started to record remains of kilns and waster heaps which were frequently discovered during construction work. From the late 1970s, the Landesmuseum at Bonn and from 1986 onwards, the LVR-Amt für Bodendenkmalpflege im Rheinland initiated archaeological investigations into the long pottery production history of Frechen.

Today evidence for pottery production in Frechen is known from about 250 archaeological investigations, ranging from the collection of a small number of fragmented wasters to large-scale excavations, including several kilns and remains of workshop infrastructure (Rosenstein 1995). The first potters seem to have operated in Frechen during the 14th and 15th centuries, but the main period started during the 16th century as a result of intensive contacts with the stoneware potters in nearby Cologne. The Frechen potters continued to produce both brown stonewares as well as green and yellow lead-glazed earthenwares into the 20th century (Figure 2).

The potters at Frechen seem to have been very reluctant to change their repertoire of forms and designs to adapt to the changing world of the 19th century. Karl Kolbach describes the situation in 1912, when just four potters were still producing traditional earthenwares, while stoneware production had already ceased around the turn of the century (Kolbach 1912, 63-65). The situation changed for the potters at Frechen in 1859 when the first railway bridge was opened in nearby Cologne, opening up the region for cheap imports of enamel dishes and industrially produced ceramics (Heeg 1992, 26-27). Prior to that, ceramics from Frechen were traded by travelling merchants and peddlers, buying their stock at the workshops.

One of the last earthenware kilns to be built at Frechen was excavated in 2019 by Andreas Vieten in the Rosmarstraße 22-24 (Vieten 2019). Unfortunately, the 19th-century buildings on the plot, probably containing the workshop and the living quarters of the Maubach family, were demolished without documentation.

At the western boundary of the property, a brick-built kiln was excavated (Figure 3). It replaced an 18th-century kiln, of which only the lower parts of the firebox survived. The new kiln was built on top, using bricks for constructing all parts of the structure (Vieten 2019, 21-31). It was a cross-draught kiln with two flues running along the rectangular firing chamber. The flues were built by eight double-arches supporting a temporary kiln floor made from laid bricks (Figure 4). A wall separated the firebox from the firing chamber, forcing the hot air to pass over it, through the stacked vessels into the flues, and finally into a large chimney at the end of the oven.

The kiln was part of the workshop of Johann Maubach and his two sons Heinrich and Peter Josef, who worked in Frechen from the second quarter of the 19th century until the death of Peter Josef Maubach in 1907 (Vieten 2019, 26-29). During the 19th century they were making slipware vessels until they were forced to switch to the production of flower pots just before 1900. Only the brothers Heinrich and Peter Mück were able to continue their craft into the 1930s by adopting new ceramic fashions, introducing products such as oven tiles, and using new techniques like mould-throwing (Heeg 1992, 26-30).

A similar situation was encountered at Bedburg-Königshoven, where in 1984 and 1985, the remains of three brick-built kilns were excavated (Schwellnus 1985, 69-70; 1987, 44). The first one was a simple cross-draught kiln with two flues constructed from a series of double arches, with the gaps bridged by bricks laid temporarily on top (Figure 5). There is no evidence for a longer period of use for this kiln, as no repairs or alterations were noticed during the course of the excavation.

Like his colleagues in Frechen, the potter at Königshoven produced large milk bowls and small pans for use in the rural kitchen (Figure 6). But he also introduced new vessel forms, usually made in contemporary creamware and other industrial whitewares, such as mugs and mould-turned saucers (Figure 7).

The use of a white glaze imitating faience or creamware and the use of different types of kiln furniture like tripod stilts and pillar-like stackers (Figure 8) indicate that the potter was trained in a pottery factory, as these features were not commonly used in 19th-century pottery workshops in the Rhineland. Handmade tripod stilts were invented during the third quarter of the 18th century in the Staffordshire area and were replaced in the middle of the 19th century by machine-made stilts (Barker 1998, 333-34; Haggarty 2006).

Probably inspired by August the Strong's porcelain factory at Meißen, in 1755 the archbishop of Cologne, Clemens August, ordered Ferdinand von Stockhausen and his brother-in-law Johan Jacob Kaisin to start manufacturing porcelain in the outbuildings of the Katzenburg chateau in Bonn-Poppelsdorf (Weisser 1980, 9-12). When they failed to discover the 'arcanum', the secret of how to make porcelain, Clemens August withdrew his financial support two years later. Without patronage, von Stockhausen and Kaisin were forced to change their business plans by switching over to the production of faience.

Between 1757 and 1805, when the business was bought by Johann Mathias Rosenkranz, the manufactory remained small, with a maximum of 15 employees, and struggled for financial success. Rosenkranz started to expand by buying the Lower Poppelsdorf mill and using it for grinding raw materials for his factory. The number of workers rose to around 80 in 1818. The end of the French occupation and the Continental Blockade marked the start of his economic decline. Rosenkranz was forced to lease his business to the ceramics and glass merchant Ludwig Wessel from Bonn in 1825. After Rosenkranz's death in 1828, Wessel acquired the Poppelsdorf mill and a plot of land next to the manufactory on which to build a new factory for faience and earthenware on it (Weisser 1980, 12-13).

Thanks to the knowledge about creamware production, acquired during extensive travels to the creamware factories in England, Ludwig Wessel and his son-in-law Karl von Thielmann started to modernise and expand their factory (Weisser 1980, 13-14). They started to use coal for firing the kilns and introduced a steam engine to power the machinery of the factory.

Unlike in craft businesses, Ludwig Wessel always looked at his company from the point of view of profitability. When, after a further expansion of the company in 1840, the purchase of raw materials from German sources became too expensive, the company began to buy kaolin from Cornwall, clay from Dorset and flint from the Normandy coast. Thanks to these international relations and the high artistic quality of the ceramics, combined with low manufacturing costs, the company also succeeded in expanding its sales to the British Empire and North America in the second half of the 19th century (Weisser 1980, 22) (Figure 9).

Excavations in 1987 revealed some remains of the original factory buildings, which were partially destroyed by later building activities on the site, as well as waster pits and at least three kilns (Figure 10).

Finds from a circular waster pit provide initial information on the faience produced during the first decades of the 19th century (Figure 11). Plates, saucers, mugs and hexagonal tea pots were produced. They show cursorily sketched flowers on a white glaze, their branches and blossoms marked out with thin black lines and then painted and completed, mostly in blue, and more rarely in green and yellow. The finds thus show a much lower quality of painting than is known from the vessels in museum collections (Haunhorst 1999, 73-87).

From another waster layer, not only were tablewares recovered but also fragments of 19th-century sanitary porcelain (Figure 12). Fragments of a toilet bowl with a decorative company logo on the inside provide evidence that sanitary porcelain was already part of the production line well before 1930, when Ludwig Wessel AG was sold to the sanitary fittings company Butzke (Weisser 1980, 43).

So despite intensive archival research (Weisser 1976; 1977) and numerous pieces in the collections of the Bonn City Museum (Haunhorst 1999) and the LVR-Freilichtmuseum Kommern (Weisser 1980), there is still much more to be learned from the archaeological remains of this important creamware and porcelain factory near Bonn. This is equally true for the other major pottery factory in Bonn, the F.A. Mehlem plant, which operated on the banks of the River Rhine south of the medieval city (Figure 13).

Some 100m east of the site of the 'Lapitesta' factory in Bonn-Duisdorf, dumped wasters were discovered during the excavation of a late medieval moated farm in 2005. They were used to fill a former pond in the first half of the 20th century (Ulbert and Strauß 2005). Saggars, kiln props, plaster moulds and wasters all came from a small factory which produced decorative flower pots and other ceramic objects for interior design (Keller 2019; 2022; Thorand 2014). The 'LWD' logo impressed into the bottom of the vessels can be identified as 'Lapitesta Werk Duisdorf'.

The excavation finds included fragments of pottery in high relief, decorated with floral and figural motifs. In addition, there were decorations showing historical scenes. A total of 12 different decorative series can be found in the archaeological finds, which consisted of off-white earthenware (Figure 14) that would have been painted in a second step.

Owing to favourable circumstances, several vessels and a large amount of historic documents from this factory have survived in the Stadtmuseum Bonn and the city archive. Additional information comes from a photo album containing eleven photos, including two in colour, taken by the Bonn photographer Theo Schafgans (Keller 2022, 224). They provide a visual tour of the factory buildings, showing the different stages of production and some of the traditional and new products in 1926.

The company was founded in 1908 by Peter August Gerhards and Johann Peter Wittelsberg, with financial support from the general practitioner Jacob Ludwig from Bonn, and produced flower vases and floristry supplies (Keller 2022, 201-3). The production range of the companies Bernhard Bertram in Lüftelberg (Figure 15), Fuss & Emons and Klein & Schard in Rheinbach, where Gerhards had previously been employed, was copied. As a result of tensions between the three partners, Gerhards left the company in 1909, followed four years later by Wittelsberger, after which the name was changed to Lapitesta Werk Duisdorf (Keller 2022, 204-7).

Since Ludwig, as a doctor, could not run the factory on his own, he was forced to employ a managing director as plant manager. After a quick succession of changes, Hubert Schüller, who had also been poached from Klein & Schard, took up the post. Schüller rearranged the product range, relying even more on copies of the most successful products of competing companies.

The labelling of the vessels with the company logo 'LWD' and a combination of numbers and letters for the model series and shape/size was also his invention (Keller 2022, 207-8). The designs for the ceramics were created by a modeller, from which plaster moulds were taken for series production. The clay was poured into these moulds by the potters. The dried vessels were fired in the kiln before being covered with coloured lacquer.

Sales were made in Germany through visits to the trade fair in Leipzig and by travelling representatives who also visited major customers in other European countries. The outbreak of the First World War caused difficulties for the company, not only because of the loss of customers in Western Europe, but also because workers were drafted and raw materials requisitioned for the military (Keller 2022, 212-23).

Despite these difficulties, unlike other ceramic factories in Bonn, production was maintained without interruption. There was even an opportunity to slowly modernise the production range, so that in the mid-1920s, in addition to the ceramics in heavy relief, smooth vases and cachepots with colourful spray designs were also produced (Keller 2022, 236-39).

The four case studies on ceramics production in the Rhineland in the 19th and 20th centuries clearly show the different tendencies that make up the transformation from craft to factory production during the main phase of industrialisation. While individual businesses, such as the Maubach pottery in Frechen, persisted in their traditional techniques and form repertoires and were therefore ultimately forced out of the market, other pottery businesses tried to adapt, constantly changing their ceramics according to contemporary tastes and selling niche products with special designs.

But even production in a manufactory in the 18th century or factory in the 19th and 20th centuries was not always economically successful. Although the Poppelsdorf faience manufactory was constantly in financial difficulties for several decades and was only able to become an internationally active company after the take-over by Ludwig Wessel (who had sufficient capital and important contacts for marketing ceramics), many attempts to produce porcelain or earthenware on an industrial scale were discontinued after a few years owing to a lack of economic success. From the Rhineland, the factories in Saarn near Mühlheim an der Ruhr, Haus Cassel near Rheinberg and Duisburg should be mentioned here (Rheinen 1913; Hackspiel 1993, 94-98; Ruppel 1989). It is precisely in these cases, where production lasted only a few years or decades and therefore few vessels could be marketed at all, that archaeological investigations offer an important insight into otherwise little-known companies and their products. However, archaeological evaluation can also expand our knowledge in the case of successful factories, whose products are preserved in museums and in private ownership in considerable numbers and for which in some cases extensive company archives and illustrated sales catalogues have been preserved.

An initial brief examination of the misfired pieces from the Ludwig Wessel factory has already provided evidence of an early production of sanitary porcelain as well as indications of a series of ceramics for export to Great Britain that are not known in the publications (Figure 9 and Figure 12). The evaluation of misfired pieces from the Villeroy & Boch factory in Wallerfangen has shown similar results. Here, a hitherto unknown export ceramic for the American market was discovered, marketed under the label 'Libertas "Prussia"' (Höpken et al. 2022; Höpken and Wilhelm 2022 ).

The possibilities offered by the evaluation of find material from production contexts for the analysis of pottery from consumer contexts should be pointed out. A cursory review of find material disposed of in a municipal landfill in Bonn at the beginning of the 20th century, which appears to have come from the less affluent neighbourhoods to the north of the old city, shows that earthenware and porcelain may have been an integral part of the petty bourgeois table. For reasons of cost, however, almost exclusively undecorated tableware without a maker's mark seem to have been purchased. Accordingly, without knowledge of the contemporary production spectrum, a more precise dating of the find complex as well as its cultural-historical classification is difficult.

Against the background of these cultural-historical questions, it is urgently necessary to process and publish the find complexes already recovered from Rhenish potteries and pottery factories as well as to protect find complexes still preserved in situ from undocumented destruction by building activities. The supposed masses of finds that might be produced in the process should not frighten us, since they represent the very last remains of an important branch of industry that must be preserved for future generations.

Thanks are due to Jozef Frantzen, Constance Höpken and Andreas Vieten for providing information and illustrations.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.