Cite this as: Giannakaki, C. 2024 The Restoration of Archaeological Sites, Old Perceptions and New Narratives: the case of Sparta, Internet Archaeology 67. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.67.19

In regions rich in archaeological heritage, such as the Mediterranean countries, archaeological theory and practice, grounded in material evidence, have played a crucial role in the construction and legitimization of collective cultural identities by tracing the lineage of present-day people back into the past. Although this approach overtime has faced criticism and scrutiny due to the emergence of the socio-political role of archaeology and in response to the rise of extreme and nationalist views (Jones 1997, 1; Grabow and Walker 2016, 28-33), its impact remains evident in Greece.

This paper examines the case study of Sparta as it is representative of the ways in which predominant views of an ancient city can affect the relationship between its cultural heritage and the local community. Several factors have influenced the study of Spartan history, including the ancient written sources and their (sometimes) temporal distance from the recorded events, the selective emphasis that scholars place on certain features of Sparta, as well as the prevailing contemporary ideological and socio-political context.

Modern scholars of Sparta challenge the established narratives regarding ancient Sparta and take a dim view of their exploitation for extreme political or ideological motives mainly on the basis of ancient written sources (Cartledge 2004; Hodkinson 2009, 2017, 2022a, 2022b; Powell 2017). The novelty of the current study lies in the fact that it discusses whether the projects that enhance Spartan archaeological sites, carried out primarily in the last two decades, can contribute to the revision of erroneous or extreme views about Sparta and Spartan society.

This analysis begins with a presentation of the established depictions and the misconceptions regarding ancient Sparta, with an emphasis on the role of the ancient sources and their challenge by modern scholarship. This is followed by a review of research at Spartan archaeological sites in relation to the expectations of scholars and the local community. In this context, factors that influenced the complicated relationship between modern society and the region's past, including the character of the sites and their delayed enhancement (conservation and restoration works to make the sites accessible to the public) are discussed. The last part of the paper presents projects that focus on the protection and promotion of cultural heritage and discusses if and how they might contribute to the formation of new narratives about ancient Sparta.

The bibliography on ancient Sparta is anything but laconic. The city's power in Classical times and its distinctive role in crucial historical events (e.g. the Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War), as well as its supposed 'otherness' in relation to the rest of the Greeks (especially Athens) (Hansen 2009, 399; Hodkinson 2009, 417-8), are some of the reasons that prompted historians and scholars since antiquity to focus on Sparta. Nonetheless, the fact that much of Spartan history is constructed from non-Spartan written sources (e.g. Herodotus and Thucydides) or from later discourses (e.g. Xenophon, Aristotle, Plutarch, etc.), led to varied and deeply diverse views about the city. From Xenophon's idealization to Aristotle's anti-Spartan arguments, the attitudes of ancient literary texts towards Sparta have largely affected modern scholarship and beliefs on the subject (Cartledge 2004; Hansen 2009; Hodkinson 2009; Powell 2017). As Powell (2017, 6) aptly points out: "With ancient writers encouraging extreme attitudes towards Sparta, whether negative or positive, it is profoundly tempting for modern observers to tend themselves towards one or the other pole".

However, regardless of the pro- or anti-Sparta views, depictions of Sparta are characterized by emphasis on exceptional features attributed to its form of government and society, such as discipline in private and public ways of life, the upbringing of children, public education, the role of women, and the system of helotage (i.e. the Spartan system of servile labour) (Hansen 2009, 399; Hodkinson 2017, 29-30). Moreover, if we had to choose one element that has been consistently highlighted as a distinctive feature of the Spartans, it would be their supposedly militaristic culture (Davies 2019; Hodkinson 2022a, 69; 2022b). If we add to this the heroic, almost mythical, dimension of certain historical events like the Battle of Thermopylae (480 BCE) have acquired, we may explain to a degree why Sparta has been treated as a discipline-driven militaristic superpower, often contrasted with democratic Athens, and why it has served as a national and patriotic model for conservative, authoritarian and far-right ideologies and regimes (Cartledge 2004, 170; Hamilakis 2012, 203-204; Davies 2019, 77; Filippo 2020, 40-41; Hodkinson 2022a).

Since the 1970s, modern scholars have challenged these predominant views about Sparta by re-evaluating ancient sources within their wider political and socio-economic contexts as well as by utilising the increased volume of archaeological evidence. Thus, it has become evident that the Classical Spartan polis was not a totalitarian militaristic state but that it exhibited features similar to those of the other Greek city-states (Cartledge 2004; Hansen 2009; Kennell 2010; Hodkinson 2017; Powell 2017). Moreover, a key parameter in contemporary studies is to identify Sparta's "[...] elements of exceptionality and her elements of normality, without the one blinding us to the existence of the other" (Hodkinson 2017, 31). However, it's not easy to change centuries-old beliefs and narratives regarding Sparta; and, as will be discussed below, especially when it comes to those of modern Spartans.

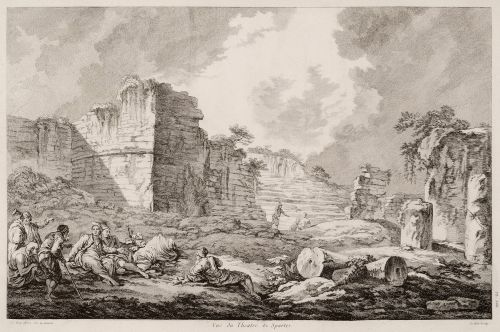

Sparta's reputation and prominent role in ancient historical and literary sources fascinated European travellers. In mainly the 18th and 19th centuries these travellers were in search of the location, the ruins and…the ghosts of the ancient polis, as Matalas (2017) convincingly argues (Figure 1). In 1834, shortly after Greece gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire, a new city was founded above the ruins of ancient Sparta (Andriotis and Georgiadis 2000). This was a highly symbolic action, mainly in the context of the "regeneration" of Greece via direct reference to the ancient Greek past (Chroni 2017, 110; Matalas 2017, 48).

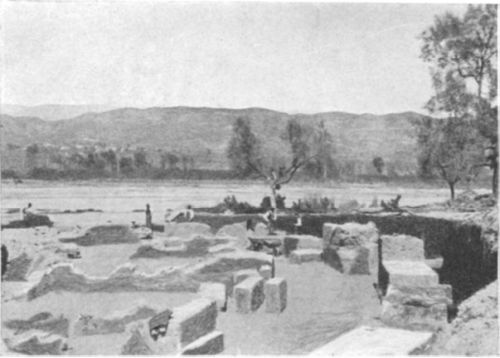

Research on the ruins of ancient Sparta began in the late 19th century and became more systematic during the first quarter of the 20th century. The activities of the Archaeological Society at Athens (an association for the excavation and promotion of Greek antiquities, founded in 1837 and active today), German and American expeditions, and primarily the British School at Athens, had focused on the central cult and public sites of the ancient city. These included the temple of Menelaus and Helen in ancient Therapne, the sanctuary of Apollo at Amykles, the sanctuary of Artemis Orthias and the area of the agora and the acropolis (Dawkins 1929; Dickins 1905-1906; Dickins 1906-1907; Woodward and Hobling 1925; Waywell 1999; Kourinou 2000) (Figure 2).

In post-war Greece, the rapid reconstruction along with the increasing demands of a developing economy, gave an impetus to the economic value of antiquities, mainly through their transformation into tourist attractions (Athanasiou and Alifragkis 2012; Beaton 2019). From the 1950s onwards, visitor numbers to Greece increased significantly (Close 2006, 101), and tourism emerged as a major driver of economic growth that determined the overall image of Greece for decades to come. During this period tourist use of specific archaeological sites (e.g., the monuments of Athens, Delphi, Olympia, Epidaurus, Delos, etc.) was promoted more systematically in order to meet the desires of visitors (Athanasiou and Alifragkis 2012, 42).

In view of the above, it is reasonable to conclude that Sparta had the potential to become an important archaeological centre and tourist destination in the post-war period. It is noteworthy that, along with Mystras, it was designated as a tourist site as early as 1950 (Royal Decree 21.01.1950, Government Gazette 27/A/26.01.1950). Notwithstanding the promising prospects, the development of organised sites in the Spartan region was not promoted systematically until the late 20th and early 21st centuries. To understand this development, we will first examine the nature of Spartan archaeological remains and their relationship with both the wider public and local society.

After World War II, particularly from the 1960s onwards, the state archaeological service, occasionally in collaboration with the Archaeological Society at Athens and the British School at Athens, carried out sporadic excavations at the central archaeological sites of Sparta (Kourinou 2000; Tsouli et al. 2015, 14; Giannakaki and Vlachou 2020). Many of these excavations were not completed, primarily due to financial constraints. In accordance with the prevailing archaeological practices at the time and the expectations of scholars, the research predominantly focused on the identification of the remains of the Classical city.

Regarding Classical Sparta Thucydides (I.10.2.) observed: "For if the city of the Lacedaemonians were deserted and the shrines and foundations of buildings preserved, I think that after the passage of considerable time there would eventually be widespread doubt that their power measured up to their reputation". (Lattimore 1998, 7-8). In support of this famous quote that underscores how the humble appearance of Sparta's temples and buildings belied the actual power of the city, the majority of the Classical period's remains are simple constructions built from local stone and generally survive in an extremely fragmentary state (Figure 3). Moreover, in locations such as the acropolis and agora, the continuous use of the area for centuries has often caused the destruction of the older structures, which lie beneath later archaeological layers (dating up to the Roman and Byzantine periods). As a result, the scarce funds earmarked for research in Sparta were not allocated to monuments that were not 'of the good times' (i.e. of the Classical period), as noted in some publications (Christou 1961, 179; Christou 1961-1962, 84). Eventually, following the establishment of the modern city on top of the ancient one, the local Ephorate of Antiquities (now named Ephorate of Antiquities of Laconia, i.e. EFALAK) had to carry out numerous rescue excavations as part of public or private projects. Therefore, the fact that the central archaeological sites of Sparta did not receive systematic state care and funding in the post-war period does not come as a surprise.

In Sparta, the desire to leverage the past for regional development and tourism promotion has been a constant. This effort began in the 19th century with the establishment of the Archaeological Museum of Sparta (1874-1876), the first purpose-built regional museum of Greece, and gained further momentum in the post-war period, when local society and authorities sought to capitalize Sparta's antiquities to boost tourism. For example, in the early 1960s, the Municipality of Spartans declared the entire city an organised archaeological site, in order to impose fees on local tourism businesses. In a document addressed to the Governor of the prefecture of Laconia, apart from the listing of archaeological sites, the Municipality argues that the name Sparta "...alone is sufficient to constitute irresistible proof for its (Sparta's) identification as a place of archaeological interest" (Archive of Ministry of Culture/Directorate for the Management of the National Archive of Monuments (DMNAM), document no. 7309/09.08.1961). In this perspective, the glorious and globally renowned name of Sparta, as a bearer of unquestionable prestige, gains self-value and stands as evidence itself. This approach endures to this day, although it is now expressed in marketing terms, such as "the brand name of Sparta".

There has generally been consensus on appeals for the restoration of monuments in Sparta, such us the large Roman theatre located on the northern outskirts of the city. Moreover, plans for the promotion of the antiquities have often been pursued collaboratively by residents, institutions, and local authorities, as evidenced by the collective initiatives and actions for the establishment of a new archaeological museum in Sparta (Spartaarchitecture 2019). However, this approach has not been consistent, and the relationship between modern Spartans and their cultural heritage can be described as occasionally controversial and complex, to say the least. As is the case with other modern cities that occupied the sites of ancient ones (e.g. Athens, Argos, Thebes), ancient architectural remains have sometimes been either destroyed or repurposed as building material (Matalas 2017, 49). Harsh criticism has also been levelled at the Archaeological Service, mainly for its deficiencies and limitations (Matalas 2000, 36; Lakonikos 2011). Additionally, even the remains themselves have been targeted, largely due to the numerous rescue excavations carried out on private land since the 1960s, which are often blamed for hindering the development of the area (Giaxoglou 2000; Matalas 2000).

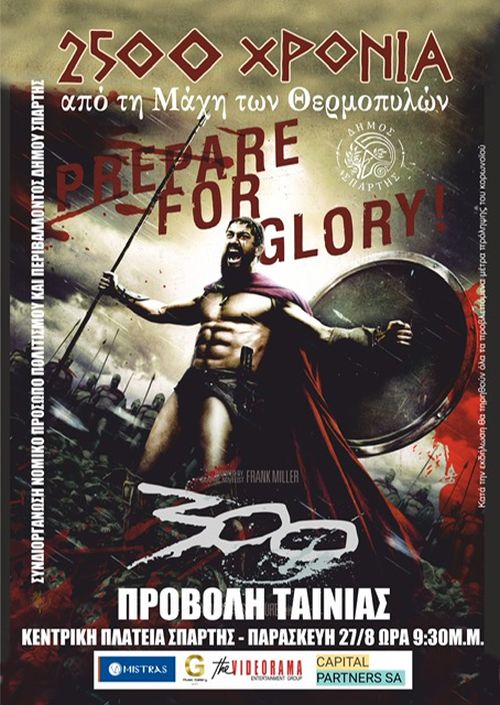

Furthermore, the gap between the material remains of ancient Sparta and the perceptions and expectations of locals and visitors regarding the region's past is undeniable and is manifested in several ways. Many aspects of the city's public life, such us the naming of streets, shops and associations, as well as public art, athletic games and public events, are characterised by emphatic references to the so called 'Spartan myth' (Cartledge 2004, 168), and its associated stereotypes (Lycurgus, Leonidas, the Three Hundred, helmets, shields, etc.) (Figure 4). Nonetheless, the simple and fragmentary archaeological remains, often referred to by locals as 'stones', do not meet collective expectations. Instead, these stones are being substituted by narratives, images, and symbols derived from the representations of ancient Sparta in contemporary Western culture (Matalas 2007). Among the fictional portrayals of ancient Sparta none has had a greater impact on modern Spartans than Zack Snyder's film '300' (2006) which focused on the Battle of Thermopylae (Cyrino 2011; Davies 2019; Filippo 2020, 40-1; Hodkinson 2022, 68). The aesthetics and themes of the film have permeated the city's everyday life, providing a wealth of narratives and visual references, even when it comes to public events and art (Figure 5, Figure 6).

Most of the contemporary views and depictions of ancient Sparta are not ground in impartial academic research. Instead they isolate and freely interpret specific elements of the Spartan history as recorded in the literature. As Davies (2019, 80) eloquently notes about the film '300': "...it is based on a graphic novel, which is based on a film, which is based on historical sources, which are based on an oral tradition derived from an event, all of which have been subjected to various shifting ideologies and cultural values which have altered or accumulated over time".

Interventions for the conservation and enhancement of Sparta's major archaeological sites have been promoted in a more systematic way over the past three decades. The Ephorate of Antiquities of Laconia has undertaken and continues to implement projects, funded by national and European Union programmes, for the restoration of monuments and archaeological sites dating from the Geometric to the Byzantine eras. These projects encompass the Eurotas River monuments, the archaeological site of the acropolis of ancient Sparta and the adjacent Byzantine monuments, the so-called 'House of Mosaics', the sanctuary of Apollo at Amykles, and more (Giannakaki 2008; Tsouli et al. 2015; Ephorate of Antiquities of Laconia 2018; Ephorate of Antiquities of Laconia 2019; Giannakaki and Vlachou 2020; Orestides et al. 2020, 31-54; Giannakaki 2022, 366-373). They involve a wide range of activities, including excavation and field work, conservation and restoration of architectural remains, photographic and architectural documentation, and the publication of informative material. Directional and information signage has been installed at the archaeological sites and monuments and paths and viewing areas have been established for the visitors (Figure 7, Figure 8).

The projects primarily hold local and national significance, contributing to broader goals of regional economic and social regeneration (Sullivan and Mackay 2012, 4; Jokilehto 2012; Williams 2015, 35). Consequently, they are considered catalysts for the growth of the Sparta region, largely due to the economic benefits derived from tourism related to cultural heritage (Orbaşli 2013, 238-240). Main objective of the interventions, which reflect rescue-oriented practices, is to establish restored, organised and accessible archaeological sites that showcase key aspects of public, private and religious life in Classical, Roman and Byzantine Sparta (Tsouli et al. 2015; Ephorate of Antiquities of Laconia 2018; Ephorate of Antiquities of Laconia 2019; Giannakaki 2022; Pantou 2022).

In line with recent advancements in public archaeology and cultural management, the projects now have a clearer social focus and aim to renew and enhance the relationship between the monuments and local community (Jeannotte 2005, 129; Carver 2012; Lipe 2012). At the same time, and despite the intention to make the antiquities accessible to diverse audiences - including the local community, visitors, scholars, and people with disabilities - these groups have not been actively involved in addressing their varied needs and perspectives within these projects. This is particularly evident in the planning and implementation phases, which are exclusively managed by the Archaeological Service, largely due to the strict legal regulations (Pantos 2001), that limit external involvement. The enhancement projects at Sparta's archaeological sites take on a more social dimension primarily after their completion and during their operational phase as evidenced by cultural and educational activities (guided tours, music concerts, theatrical performances, exhibitions, lectures, etc.) held at the sites, all designed to engage the broader public (Katsougkraki 2017, 184-185; Tsouli and Giannakaki 2017, 183-184; Giannakaki 2022, 370-371).

In terms of the selection of narratives during the design and operational phases of a project, archaeologists have to deal with multiple, competing ideologies and interpretations of the region's past (Jones 1997, 10; Van Dyke 2011, 234). These interpretations, as previously discussed, are often shaped by contemporary socio-political contexts, academic debates, and the vested interests of various stakeholders, including local communities, authorities and tourists. Such a complex landscape necessitates a careful and balanced approach to narrative selection, ensuring that the chosen narratives are as inclusive and representative as possible.

Against this background, the review and revision of obscure or false views and narratives on ancient Sparta becomes a significant challenge. Therefore, emphasis is placed on the understanding of the site by the general public, mainly through the presentation of valid archaeological and historical information. By presenting well-researched and peer-reviewed information, archaeologists aim to foster a more nuanced and accurate understanding of ancient Sparta, countering myths with evidence-based narratives. Once the sites are open to the public this effort involves not only correcting misconceptions but also engaging in public education and outreach programmes. Informational signage, guided tours and educational programmes at the archaeological sites, as well as at the Archaeological Museum of Sparta, all can play crucial roles in this effort. However, this remains a one-way process, determined exclusively by experts and directed at a disengaged general public (Smith 2006, 104-105).

A critical question arises at this point: Can the restored archaeological sites of Sparta prompt a re-evaluation or revision of established perceptions and narratives about ancient Sparta? As stakeholders in their archaeological heritage local residents and groups act as 'living carriers' of this heritage, influencing and simultaneously being influenced by the changes occurring at the archaeological sites (Gόral 2015). However, as noted, they are not actively engaged in these projects. To achieve the goals of these initiatives and ensure a lasting impact on both the antiquities and the local society, it is essential to integrate monument protection with community involvement. This can be achieved by leveraging existing knowledge on the interactions between restored monuments and various stakeholders and by striving to balance archaeological, social, economic and environmental outcomes (Vlizos 2022: 47).

Within this framework, developing the narrative of a site requires thorough research that incorporates archaeological, historical, environmental, social, and other evidence associated with the monument (Sullivan 1997, 20). Under the guidance of the Archaeological Service, this process should engage a wide range of disciplines and consider the perspectives of the diverse audiences that interact with the monuments (Ferroni 2012, 542).

In this respect, structured and accountable decision-making requires active discussion and dialogue about the ways in which the different groups and individuals approach and interpret the past. Therefore, it is crucial to identify and engage with multiple audiences. This involves not only recording their perceptions and expectations of the past and its remains but also understanding how these perceptions shape their interactions with heritage sites. To achieve this an extensive audience research is essential. This research should include surveys, interviews and focus groups with various stakeholders, including local communities, historians, archaeologists, educators, and visitors. This process should be iterative, allowing for ongoing feedback and adjustments to strategies as new insights emerge. Ultimately, incorporating these diverse viewpoints into decision-making helps ensure that heritage management and presentation are more inclusive, relevant, and engaging for all stakeholders involved (MacMillan 2010; Grabow and Walker 2016; Kalman and Létourneau 2020).

Given the widely adopted narratives on Sparta's diachronic history, the research should be structured around the following key topics:

This paper argues that, under certain conditions, the enhancement of archaeological sites in Sparta can generate new narratives and contribute to the revitalization of Sparta's contemporary identity. This requires strategic planning and the establishment of clear objectives for the preparation, implementation and operational phases of the projects. To this end it is crucial for the Archaeological Service to actively engage in dialogue about how various audiences perceive and interpret the past, even within the bounds of legal constraints.

Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude to John Halsted (HS2 Ltd) and Tomomi Fushiya (University of Warsaw) for accepting the paper I presented at the 29th Annual International Conference of the European Association of Archaeologists (EAA) held in Belfast in 2023 and for the opportunity to publish this work in Internet Archaeology. My appreciation extends to the journal for accepting my paper, and especially to editor Judith Winters for her exceptional collaboration, meticulous editing, and insightful comments.

This article is part of my ongoing doctoral research on the conservation and enhancement of archaeological sites in post-war Greece, conducted at the Department of Archives, Library Science, and Museology at Ionian University. I am deeply grateful to my supervisor, Associate Professor Stavros Vlizos, for his invaluable guidance and encouragement throughout the writing process.

Lastly, I would like to thank Dr. Evangelia Pantou, Director of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Laconia, and Dr. Maria Tsouli, Head of the Prehistoric and Classical Department of the Ephorate, for granting permission to publish images from the Ephorate's archive. Access to archival material from The Directorate for the Management of the National Archive of Monuments of the Ministry of Culture was granted under study permit (ΥΠΠΟΑ/ΓΔΑΠΚ/ΔΔΕΑΜ/ΤΔΙΑΑΑ/Φ.410/302009/ 212865/816/145/03.07.2020).

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.