Cite this as: Recht, L., Zeman-Wiśniewska, K. and Mazzotta, L. 2024 Excavations at the Late Bronze Age site of Erimi-Pitharka, Cyprus (2022-2023 seasons): Regional production and storage in the Kouris Valley, Internet Archaeology 67. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.67.6

The rural site of Erimi-Pitharka is located in the archaeologically rich Kouris Valley of south-central Cyprus (Figure 1A-C). Dated to Late Cypriot (LC) IIC-IIIA (c. 1300-1150 BCE), Pitharka is characterised by an emphasis on agricultural production and storage. The inhabitants of the site took advantage of the soft limestone-rich bedrock to create subterranean and semi-subterranean installations, rooms and storage spaces, and pithoi (large storage jars), bathtubs (deep basins) and groundstone tools were similarly used for storage and industrial activities. While there is some evidence of long-distance connections in the form of imported ceramics, the majority of the material culture appears to be from local or regional production. The site was peacefully abandoned, probably in the earlier part of the LC IIIA period (c. 1200-1150 BCE), and much of the material culture was removed in the process. Previous rescue excavations by the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus, have revealed a subterranean complex, industrial areas, and a building complex at the highest topographical point of the site (Area I). New excavations by an international team from the University of Graz and Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University, Warsaw, began in 2022 and continued in 2023. We here report on the findings from these first two seasons and briefly discuss the role of Pitharka as a site of production and storage in the Kouris Valley in the Late Bronze Age.

The site of Erimi-Pitharka is located in the town of Erimi, in the Kouris Valley, within Limassol District (Figure 1A-C). It is roughly 100-110m above sea level, on the eastern bank of the Kouris River, now dried out as a result of a modern dam about 6km to the north. The valley is rich in archaeological sites, spanning a period from the Neolithic, through the Chalcolithic and the Bronze Age up to the Roman and Byzantine city of Kourion on the coast (for overviews of sites and surveys, see e.g. Violaris 2012; Bombardieri and Chelazzi 2015; Kopanias et al. 2022; for a chronological table of the prehistoric and protohistoric period in Cyprus and Levant, see Recht and Bürge 2023, table 1.1). The eastern bank of the Kouris river consists of a limestone upland plateau, where small fertile valleys were preferred in the Middle and Late Bronze Age, while the western bank with river terraces has more Hellenistic and Roman activity (Bombardieri and Chelazzi 2015, 114-15). Erimi itself is perhaps best known for the so-called Erimi culture, now more commonly incorporated into the Chalcolithic archaeological sequence of Cyprus (c. 4000-2400 BCE). It was named after the site of Erimi-Pamboula, excavated by Porphyrios Dikaios in the 1930s (Dikaios 1934); the material was later analysed in detail and published by Bolger (1988). The Kouris Valley continued to be an active area for settlement and burial in the Bronze Age. An important site includes the Middle Cypriot settlement, workshop area and cemetery of Erimi-Laonin tou Porakou, which is located a few kilometres north of Pitharka, on a high plateau on the eastern river bank. It has been excavated since 2008 by an Italian Mission (Bombardieri 2017).

Immediately north of Pitharka is Erimi-Kafkalla, a cemetery consisting primarily of Early and Middle Cypriot tombs, excavated by the Department of Antiquities (Violaris 2012). The site is named after the type of calcareous bedrock that is typical of the area, including at Pitharka. This is a soft limestone that is referred to in the literature as either kafkalla or havara/chavara (Schirmer 1998). A large number of tombs were excavated, and alongside them also mortar-like and basin installations, which were cut directly into the bedrock (Bombardieri and Chelazzi 2015, 120). In addition to the many Early and Late Cypriot tombs, five of the tombs (all cut into bedrock) have been identified as Late Cypriot (MC III-LC IIC, c. 1750-1200 BCE). This makes them partly contemporary with Pitharka, and Violaris also suggests that they are associated with the settlement (Violaris 2012, 53). Unfortunately, their exact location is no longer known, and no plans have been preserved. Some installations at Kafkalla may also date to the Late Cypriot period. For example, an olive press, again cut into the bedrock, was discovered during a survey in 2004, and is thought to have been in use from the Neolithic to the Late Bronze Age (Belgiorno 2005).

About 1.5km south-west of Pitharka is the site of Episkopi-Bamboula, a settlement and cemetery dated to LC IA-IIIA (c. 1600-1150 BCE, Benson 1972; Weinberg 1983), and just south of this is Episkopi-Phaneromeni, a small LC IA settlement with some signs of earlier occupation (Carpenter 1981; Swiny 1986). To the north, at the modern Kouris Dam, is the site of Alassa (Paliotaverna and Mano Mantilaris), famous for its ashlar masonry, and dated to LC IIC-IIIA (Hadjisavvas 2017). The status of Pitharka within this network of Kouris Valley sites is not yet clear, but they share much of the same material culture, suggesting similar practices within the rural landscape of the valley.

In October 2001, a subterranean complex was discovered at Pitharka during clearing for building. The complex was subsequently excavated by the Department of Antiquities and published in a short report (Figure 1C, Vassiliou and Stylianou 2004). It consists of seven chambers connected and divided by corridors, walls and low benches. There are air vents in several places, and tool marks on the walls testify to artificial cutting of the structure, although it is not clear if these are modifications to a natural subterranean cavity or entirely created by humans. The finds from the chambers and corridors include many stone tools and ceramic sherds, a bovine figurine, a well-preserved stepped capital, and a few human and animal bones. The pottery (primarily pithoi, but also Plain White, Monochrome, Aegean-type, cooking and imported Canaanite and Mycenaean ware) indicates a date of LC IIIA-B (c. 1200-1050 BCE), and the short report suggests that the complex was used for domestic and/or industrial and storage purposes. Several similar structures are known to be present in the vicinity, including one to the east, and another to the south, which are now covered by a modern road; no other subterranean structures of this size have been excavated. After excavation, the cave was also restored and roofed (see Flourentzos 2010a, 55-56).

Between 2007-2012, further rescue excavations were conducted by the Department of Antiquities on the site in response to building activities, and several plots were expropriated as a result of the findings. These have been published in short preliminary reports (Flourentzos 2010b; Papanikolaou 2012). The excavations were carried out in four areas, labelled I-IV (detailed plan not published, but see overview in Flourentzos 2010b, fig. 29).

In Area I, part of a large building was excavated, possibly an administrative building, with stone foundations and mudbrick superstructure (Papanikolaou 2012, fig. 1). It occupies a central position in the local topography (Figure 1C, area within modern cement wall). The rooms were laid out in two rows, and successive stages of construction may be detected. There is also evidence of a terracotta drain. South of the building there was an open-air space with a so-called bathtub (deep oval basin) in situ. Another bathtub with an associated drain was also found in the northern part of the building. The finds include pottery, stone tools, metal objects, and human and animal remains. There were many sherds of pithos and bathtub among the pottery, but also imported wares, Plain White ware and typical Late Cypriot (LC) wares. The pottery suggests a date of LC IIC-IIIA (c. 1300-1150 BCE), while there are also some LC I-II wares (Base Ring I, White Slip I, c. 1600-1300 BCE).

In Area II, there were remains of long walls following the slope of the valley down to the river, believed to be retaining walls used for reinforcement. In the north-western part is a large building that may have functioned as an observation post. Several workshop areas and installations were also identified in this area, with basins and canals cut into the bedrock, some possibly for collecting rain water. Two rock-cut caves were partially excavated. Area III, south of Area II, is characterised by three walls following the slope of the valley which are thought to be retaining walls. Area IV is east of Area I. It consists of parts of buildings and workshops, including features cut into the bedrock. Some evidence of intramural burials in the form of skeletal remains of two individuals below the foundations in Area I, and another burial in an oval pit, were recovered from these excavations.

The finds include pottery - pithos, cooking/coarse ware, Plain White Handmade and Wheelmade, Base Ring I and II, White Slip II, Aegean-type ware, imported Mycenaean, Minoan and Canaanite vessels, stone tools (chipped stone, grinding stone, grinders) and gaming stones. The few metal finds include a well-preserved ploughshare.

New excavations were carried out by the University of Graz and Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University, Warsaw in July-August 2022 and April-May 2023. The project is directed by Lærke Recht (University of Graz, Austria), Katarzyna Zeman-Wiśniewska (Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University, Warsaw, Poland) and Lorenzo Mazzotta (University of Salento, Lecce, Italy), with a team of students and experts from Austria, USA, Poland, Greece and Cyprus. In 2022, a Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) survey was conducted before the beginning of excavation.

The aims of the project are twofold: to understand the character of Pitharka in terms of economy, subsistence, function and societal development, and to investigate its role in the settlement and mortuary landscape of the Kouris Valley, both spatially and chronologically.

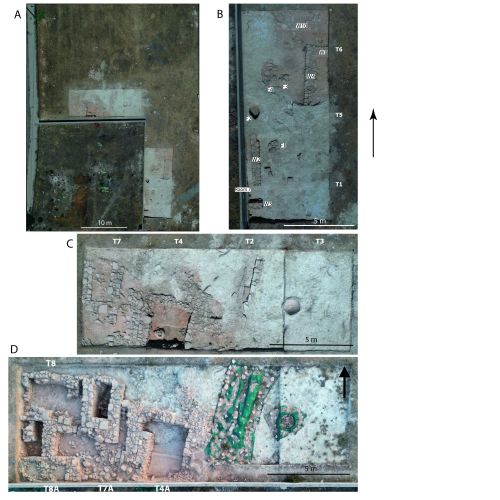

During the first week of the 2022 season, a geophysical survey (GPR) was conducted by Fabian Welc (Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University, Warsaw) on plots 1111, 1209 and 1210 (the northern part of the black rectangle marked on Figure 1C; see also Figure 2A). GPR is a mobile and highly effective method of surface geophysical prospection and which applies the phenomenon of wave reflection from the geological boundaries of media differing in the dielectric constant and electrical resistivity, depending on the lithology of a given medium and the degree of its water saturation. The results of the survey will be published in a separate paper. Briefly, it can be said that, at first glance, the arrangement of the identified walls seems somewhat chaotic. What must be emphasised here is the fact that walls constructed using sandstone with an admixture of clayey matter that are surrounded by weathered rock of a very similar lithological composition, may not be visible in the GPR images. It thus seems that only structures that are well preserved and have a significant wall thickness can be traced by the GPR planes. With this in mind, analysis of the images suggests the presence of several complexes or structures consisting of numerous smaller rooms. Further, the integration of the information from the GPR profiling results, aerial photographs, and archaeological excavation revealed an overlap of some anomalies within the course of the excavated walls.

Based on the preliminary GPR results, the plans of the previous excavations by the Department of Antiquities, and visible remains on the surface, trenches were opened in 2022 directly to the north and to the east of Area I which is within the modern concrete wall (Figure 1C, Figure 2A-C). This new area is labelled Area 1A to show its connection with the earlier excavations. In this part of the site, the archaeological remains are very close to the surface, in some places even visible. Some disturbance has been caused by recent building and other activities at the site, but is less severe since the area was fenced off by the Department of Antiquities. For the 2023 season, excavations were focused on the continuation and extension of the northern trenches (Figure 2D, Figure 11).

Area 1A is a building complex of connected rooms interspersed with exterior spaces and an exterior space to the north and east of the trenches. To the south, the walls connect with the earlier excavations, and reveal a sequence of rooms connected by a corridor. The structure also extends to the west, which is now below the modern road. The whole complex in Area I/1A was primarily used for storage and industry related to agricultural production on a regional scale. It appears to have been peacefully abandoned in connection with or following a widespread collapse of stone walls and their mudbrick superstructure.

Trenches 1, 5 and 6 were opened east of the modern cement wall which marks the limits of the previous rescue excavations. The locations of these three trenches were also selected to better identify possible connections with the archaeological remains previously uncovered in Area I. T1, T5 and T6 are placed side by side in a north-south direction, each measuring 6 × 5m (Figure 2B).

The surface of T1 has been affected by modern activities including a patch of asphalt road and a thick preparation layer of pebbles placed during the construction that occurred in the area before this was expropriated. Below a shallow layer of colluvial soil and modern disturbance, the eastern part of T1 was dominated by a homogeneous white and compact calcareous layer (the natural soil of the site, the so-called kafkalla). This extends to the north into T5 and T6 and did not contain any finds, suggesting an exterior space. The western part of T1 was covered by a thick and dense layer of decayed red mudbrick material, fallen stones and mixed ceramics, apparently the result of an extensive collapse. Below this collapse were the remains of two walls (W2 and W3, located at the eastern limits of the trench, just next to the modern cement wall).

W2 runs parallel to the modern cement wall in a north-south direction for 3.70m, while W3 is at right-angles to it and goes in an east-west direction. W3 connects with a wall from the earlier excavations on the other side of the modern cement wall (Area I), to what was labelled Room 7, clearly demonstrating the continuation of the building uncovered during the previous campaigns (Papanikolaou 2012, fig. 1). The walls are built using medium to large stones, some partially cut and carefully placed to create solid walls. They consist of 1-3 courses (0.24m deep) and have a width of 0.57m. Below W2 and W3, as well as below the associated use surfaces, a thick layer of red, compact soil was found. This had been intentionally deposited prior to the construction of the walls in order to flatten the whole area, which is characterised by a significant downsloping and unevenness of the natural sediment. The same architectural strategy is documented for walls in T4, T5 and T6. Room 7 could be entered from the east through a doorway between W2 and W3 in the south-eastern corner of the room.

T5 is north of T1. Below the disturbed and colluvial soil, there was a collapse represented by red, compact mudbrick and stones in the south-western area and another of the same composition in the north-eastern part of the trench. Below the south-western collapse was the continuation of W2 toward the north, for about a metre into T5. No corner was found at the northern and finished limit of W2, suggesting either another entrance or that the room was open to the north. The stratigraphy visible in the section between the bottom of W2 and the upper surface of the natural sediment confirms that the area was intentionally levelled with a thick layer of soil in order to fill the concavities of the natural sediment to create a flattened surface suitable for building the wall, as was the case in T1 and for W3.

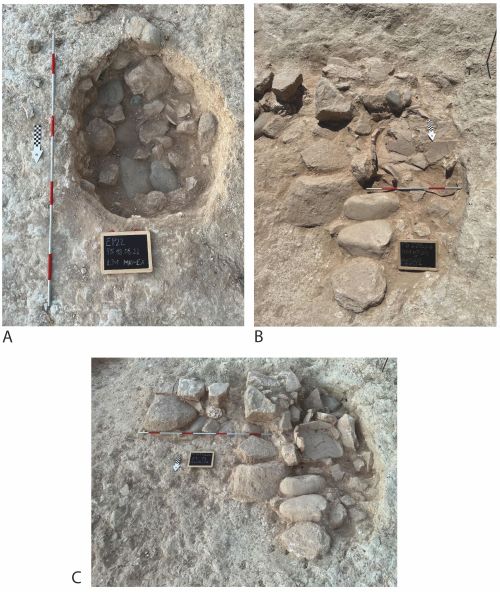

East of W2, a squared and flat installation of carefully placed medium and large stones was found (F1), contemporaneous with the surfaces associated with W2 and W3. The specific function of this feature is not clear, but must be related to the activities carried on outside the area east of Room 7. From the outside surface associated with the use of both W2 and F1 comes a fragment of White Slip II Early (L18-P1) which may suggest the existence of older phases of the settlement. In the same exterior area, north of W2, there was an oval pit (0.75 × 0.90m) cut in the natural sediment (F2), which was about 0.60m deep, as excavated (Figure 2B, Figure 3A). It contained a fairly high concentration of the usual ceramic wares of pithos, Plain White, cooking/coarse ware, Base Ring, White Painted Wheelmade, and a single imported Mycenaean ware sherd, and there were a number of groundstone tools found in it (FN9, FN11, L36 s#77). The pit has not yet fully excavated. It may have been used for storage or functioned as part of a production process, and then later reused as a dump.

Below the collapse in the north-eastern corner of T5, there was another wall, orientated in a north-south direction (W4), and the associated surfaces on both its sides. W4 is perpendicular to a neat cut made in the natural sediment in order to set the building at the lowest possible level into a large depression. This wall continues north into T6.

The southern area of T6, north of T5, was covered by the same collapse of stones and mudbrick material belonging to W4 already excavated in T5. A grinding stone (FN18) and a grinder/pounder (FN13) were found in this collapse. The continuation of W4 is below this collapse, continuing for 1.60m up to a corner with W8, turning east and marking a new room in that direction. The room is still unexcavated, with W8 continuing to the west into the section of the trench. Both walls are about 0.90m wide, with one to two excavated courses of stones (0.20m in height).

Another two installations or platforms of stones placed close together were discovered below the same collapse in the south-western part of T6 (F3 and F4), located in the area west of W4 and separated from it by an empty space, which provided passage in a north-south direction. Immediately against and clearly associated with F4 on the west, a fragmented pithos (L28-P17), a partially preserved pierced bathtub and a stone basin were found covered by the collapse of mudbricks and stones in the narrow space between F4 and the cut in the bedrock that marks the western limit of the same collapse (Figure 3B-C). This installation and the bathtub, with its pierced base, may be related to activities involving liquids.

Finally, a second corner formed by two connecting walls (W10) in the northern part of the trench suggests another room, possibly associated with a larger platform on its western side. W10 runs roughly east-west, in alignment with W8 and perhaps with a corridor between them. The second wall connects from the eastern corner to the north. These walls were discovered at the end of the season, and only the top course has been exposed.

The pottery collected from the collapse and from the use surfaces associated with all these walls and installations in the eastern trenches consists mostly of pithos, Plain Ware, cooking/coarse ware, while fewer sherds of Base Ring, White Slip II, Aegean-type ware, and Mycenaean and Minoan imports dated to Late Helladic (LH)/ Late Minoan (LM) IIIA2-B, suggest an LC IIC date.

Four 6 × 4m trenches were opened in Plot 1111 in 2022: T2, T3, T4, T7. These trenches are placed next to each other in an east-west line north of the modern cement wall and the previous excavations in Area I (Figure 2A, 2C, Figure 11). In 2023, Trenches 4 and 7 were exposed further (each 6 × 4m), a new Trench 8 was opened to the west (6 × 4m), and three small trenches were opened south of these, in order to uncover the structures near the modern cement wall (Trenches 4A, 7A and 8A, each 1 × 4m, Figure 2D, Figure 11).

Trench 2 was the first trench opened in the northern area. It was placed based on a row of stones visible on the surface believed to be a wall, in combination with the GPR results. The stones did indeed turn out to be a wall (W1), about 4m long in a roughly north-south direction. On the western face, the stones are nicely cut to create an almost flat facade, while the eastern face is uneven and appears to be unfinished. Only one course of the wall is preserved, but along its western side were the remains of a terracotta drain. Both the wall and the drain have been placed in a cut in the bedrock. The drain is set into and partially filled with mudbrick material, and a higher concentration of pottery was found both in the drain and between it and the wall. This includes pithos sherds, coarse ware, and White Slip II and Base Ring, suggesting an LC IIC date. In the north, W1 ends just before the northern section of the trench, and in the south it has been disturbed, but it is not clear if this disturbance is the result of modern or ancient activities. Unfortunately, it means that the wall and drain are no longer associated with any other features, and it is not possible to determine either the beginning or end point of the drain, or its more precise function. A terracotta drain was also found in the earlier excavations where it ran below a later wall (Papanikolaou 2012, fig. 2).

In the south-western corner of the trench, there was a concentration of deteriorated red mudbrick material and small and medium-sized stones. These were possibly the remains of an installation which is now entirely destroyed. The western part of the trench otherwise mainly consisted of the hard white sediment that we now recognise to be the limestone-like bedrock at the site. The eastern part of the trench contained the same bedrock except for a small circular feature in the northern part. This feature was roughly 0.30m in diameter and very shallow; it may have been a posthole. In the eastern section, we also found a large vertically placed part of a pithos, and therefore extended in this direction (T3).

Trench 3 is directly east of T2 and was opened due to the presence of part of a pithos in the eastern section of T2. This turned out to be the complete lower part of a pithos, still in situ which was placed in a custom-made cut in the bedrock. Roughly the lower third of the vessel was preserved. This preserved part can contain c. 125 litres, suggesting that the complete vessel could have possibly contained about 300 litres. The pithos had partially collapsed in on itself, as evidenced by the many pithos sherds found inside it. Pithoi sunk into floors or pits can be found at a number of Late Bronze Age sites, including at nearby Alassa and Kourion-Bampoula (Pilides 2000, 34-39). There were no additional anthropogenic features in the rest of the trench, and it appears that the pithos was set in an open or semi-open space, possibly a courtyard.

Trench 4 is west of T2. Excavation was started in 2022 and continued in 2023; in 2023, Trench 4A was added as a southern extension of 1m, up to the modern cement wall. The southern half of T4 and all of T4A are dominated by Room 101, its walls (which also slightly extend into T7/T7A), and a stone collapse in the south-east. T4 is much disturbed to the north and somewhat in the eastern part into T2. A heterogeneous and mixed layer separated the colluvial from the walls and more secure contexts.

Room 101

R101 is an interior space of 2.20 × 3.70m as excavated (Figure 4, 3D model 1). It is surrounded by drystone walls, with the eastern, northern and western walls preserved (W5, W7, W11), while its southern limit lies beyond the southern section of T4A. The continued excavation demonstrated that the western wall (W11) extends further south and to a depth of 0.80m. The northern wall (W7) was instead placed on top of the bedrock, which has been cut vertically to create the inner space of the room. The room was filled with decayed mudbrick material and stone collapse from the upper part of the walls, with stones especially evident in the upper layers. These loci included the restorable lower part of a closed Plain White vessel (L20-P3), several Mycenaean sherds, and a substantial amount of groundstone tools, mostly broken grinding stones (FN5, FN8, FN12, FN14, L56-ST1 and L65-ST1).

The lower part of the fill contained the upper half of a narrow-necked pithos near W11 (L43-P2) (Figure 4A). The upper half was fractured but still complete, apart from some of the rim, and decorated with linear plastic bands. It had possibly been thrown in, since it was partly sitting on some stones and itself contained a large grinding stone (FN17, Figure 7). A sort of stepped construction of grinding stones (L82-ST1, L82-ST2) and other medium-sized stones was placed at the same level as the bottom of the pithos, but on the other side of the room, against W5.

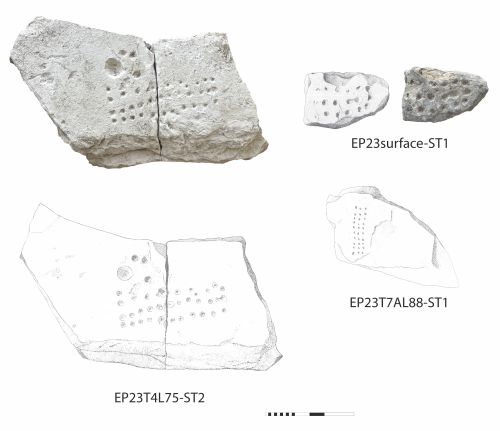

Towards the bottom of the room, there were two levels of partially preserved plaster floors associated with a mudbrick installation of unknown function. Near and surrounding these, there was a thick layer of dark ash, demonstrating that at some point the northern part of the room was burnt (Figure 4B). The pottery found in these lower layers was primarily Plain White, fine ware (including Base Ring) and cooking ware. The lowest layer of white plaster floor was directly on top of a large flat stone which proved to be a gaming stone turned upside down (L75-ST2) (Figure 4C). Other finds within this part of the room included a bronze pin (FN19), groundstone tools (Figure 8, L50-ST1 pestle, L56-ST1 grinding stone, L75-ST1 part of vessel, L82-ST1 and ST2, grinding stones) and part of a terracotta drain (FN20).

The southern part of the room was not burnt, and there was a clear dividing line between the two areas of the room - with the southern wall still outside the area of the trench on the other side of the modern cement wall. The southern part of the room does not have the same preserved floor, but a fill of light brown soil, and a stone collapse or disturbance in the south-eastern corner. In the south-western corner, in the section below the cement wall, part of a large jar was preserved with part of its body still vertically in situ (visible in Figure 4C-D). Below the brown fill and the two partially preserved plaster floors (L75, L74, L80), there was another, very different type of plaster floor which is extremely well preserved and about 10mm thick (Figure 4D, 3D model 1). It is very smooth and flat, except for a slope or ridge from east to west along the previously noted dividing line (with a difference in height of about 70mm). This floor covers the entire southern half of the exposed room, and the plaster slightly curves upwards near the walls. As with the rest of the room, we do not have its southern limit, but there is a rectangular cut or indent in the south-western corner, suggesting an irregular original outline of the floor. The careful plastering, evenness, curving at the walls and the ridge suggest that this space was related to production involving liquids. A comparative floor was found at Pyla-Kokkinokremos, which had similar curving and an associated drain (Bretschneider et al. 2017, 103-5, Space 5.7).

There is an entrance to the room in the north-western corner. At some point, this entrance was blocked with densely packed stones, perhaps before the burning event. The fill of the entrance contained a picrolite finger ring (FN21, Figure 10). On the western side, the entrance was also blocked by W16 in an earlier event. There is a greater concentration of pottery in the room than in most other spaces, although the overall amount is still fairly low. It includes pithos, Plain White, and coarse ware, with some Aegean-type ware in the upper loci. The presence of Base Ring (I and II) suggests an LC IIC date.

These trenches are west of T4. W11 of Room 101 is at the eastern limit of T7, slightly into it. Below the colluvial soil, the collapse and sequence of rooms continue, with a corridor, several additional interior and exterior spaces and evidence for at least two architectural phases.

Corridor

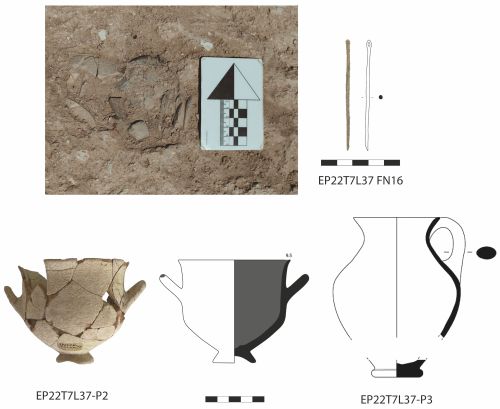

W16 was built running roughly north to south, parallel to and directly against W11, which is the western wall of R101. It is quite wide at 0.90m, and at least 0.65m deep. Between W14 and W16, there is a narrow corridor roughly 0.55m wide. The corridor was packed with quite large stones from either a collapse or a deliberate blocking or closing off of the space. W16 does not connect to any other walls to create a corner (at least as preserved), but its presence both significantly diminishes the space of the corridor and blocks access to R101. In the south, the corridor turns at a 90 degree angle into what appears to be an entrance into Room 104. In the southern part of the corridor, there were two vessels placed on their sides with their openings against each other along with a small intact bronze needle (FN16) (Figure 5). This is surely not a random deposition, but its meaning still needs to be clarified. It is remarkable that the vessels seem to have been placed on top of the general collapse in the corridor. One vessel is an Aegean-type bell-shaped skyphos with a high conical base and monochrome interior and the other is a small raised flat-based and wheelmade cooking pot. These suggest an LC IIIA date for this particular context and a continued use or revisiting of at least some parts of the site.

Within the collapse, one grinding stone was found (L70-ST1). Not much other pottery was found in the corridor, mostly pithos sherds, with some Plain White, and coarse/cooking ware. Aegean-type ware is represented in the upper layers, and a Base Ring sherd in a lower layer.

Room 102

On the other side of the corridor (to the west), there is another room on the same alignment as R101, but further north, labelled R102. This is a small rectangular space (1.10 × 2.20m) surrounded by four walls in its latest phase (W12, W13, W14, W15). However, the space must once have been larger, since W13 is only one course deep, and represents a late division of the room. At this stage, we do not have a preserved entrance and do not know how R102 was accessed. W12, W14 and W15 are instead much deeper and with well-constructed walls that were built in an earlier period but reused within R102. In the uppermost courses of W12, there was a grinding stone and a broken three-legged stone mortar (W12-ST1, Figure 12C) which had been reused as wall elements. There is evidence of collapse inside the room in the form of mudbrick debris and some fallen stones from the upper parts of the walls in the highest layer.

North of the complex of rooms in T7 and T8 (R102, R103, R106, R107), there is an exterior space with a pebble and limestone surface. The fill above the surface included finds of a grinder (L45-ST1) and a grinding stone (L45-ST2), and the pottery mostly consists of a higher than usual concentration of Plain White ware sherds, with a few pithos, coarse/cooking ware and White Painted Wheelmade sherds. A single Base Ring sherd also comes from this area.

Room 103

R103 is the space directly west of R102. Its walls are badly preserved and mostly made of single lines of stones, except for its eastern boundary (W13), shared with R102. To the north is W19, which, despite its alignment, does not seem to be a direct extension of W12. It is very uneven, with a single line of stones, and its depth is unclear until its western part, where it consists of two courses and a depth of at least 0.50m, but this may be a reuse from an earlier phase. To the west, the boundary may have been W20 (although this is an earlier wall, and may not have been contemporary with R103), which is also deeper and seemingly of greater width, but partly in the western section of T8. The southern limit of the room is less well preserved, and may have consisted of an extension of W15, now much disturbed. One loomweight was found in the room (FN23), along with the usual types of LC IIC pottery.

R102 and R103 represent a later phase, and an architectural rearrangement of the space in this area from that of the earlier R106 and R107 (see below).

Room 104

Stretching across T7 and T8, south of R102 and R103, is R104. In the east, the room connects with the corridor in T7 by a 90 degree turn at the corner of W14. The space is roughly 1.55 × 4m from east to west, but the boundaries are not entirely clear owing to disturbance of walls and much collapse throughout the area. Nevertheless, in its earlier phase, W18 was the western limit, W21 the limit in the south-west, and W15 the limit in the north-east. At a later stage, another wall may have been built directly against and south of W15, perhaps also to block access to the rooms to the north. There was a large patch of decayed mudbrick in the eastern part of the space, which may have been some sort of installation rather than simply collapse given its location, size and concentration. In the corner of W18 and the extension of W15, the lower half of a large Plain White jar or jug (L60-P2, Figure 7) was preserved in situ, apparently placed into the ground. Several grinding stones were found at roughly the same level (L71-ST1, L71-ST2) and, slightly lower, a grinding stone (L81-ST1) and part of a stone vessel or basin (L81-ST2).

At a lower level, in the centre of the western part of the room, a nearly complete Canaanite transport jar (Figure 7, L84-P2, missing only the neck and rim) was found lying on its side, surrounded by medium-sized stones and other ceramic sherds, giving the impression of more collapsed or fallen material. The jar has a Cypro-Minoan potmark incised on one of its handles (sign CM006, Olivier 2007, 414. We are grateful to Cassandra Donnolly for this reference and first identification of the sign). No associated floor was identified, but the context is clearly related to the use of W21 and W18.

Room 105

R105 is located west of R104 and south of R103, and is surrounded by three quite well-built walls: W18 to the east, W21 to the south, and W23 to the north. W18 in particular is quite wide, at 0.80m, and seems to have been built against W21. The full extent of the room is not known, as it continues to the west, into the section of T8. The excavated interior space is about 2.25 × 1.50m from north to south. The walls are at least 0.50m deep, but a floor has not yet been reached. There is again much evidence of collapse and fallen stones in the room. Within the room, there is another, earlier, wall (W24) that is quite wide (0.70m), at least 0.50m deep, and built with large field and waterworn stones. It starts roughly in the centre of the room and goes north as far as and perhaps below W23, but is not aligned with any other structure in the trenches. This may therefore be a wall of a space pre-dating R105 and the nearby rooms. The lower levels of this room include a gaming stone (L83-ST1), a handstone (L83-ST2), two grinding stones (L83-ST3, L92-ST2) and a worked stone, perhaps a mortar (L92-ST1).

Room 106

An earlier phase is represented by R106 and R107, which are below R102 and R103 (Figure 11A-B). R106 is the space within W12, W14, W15 and W17, covering about 2.80 × 2.20m, and with walls over 1.40m deep, as excavated. Apart from W12, all the walls are quite broad (c. 0.65m), and all are very well built with large field stones and river stones. Some also have large corner stones. There is an entrance in the south-west, between W15 and W17, which is c. 0.75m wide and marked by corner stones. This entrance was at some point filled by a collapse or deliberately blocked with many medium-sized and large stones. W17 has been disturbed, possibly by a pit, as the central part of the wall is missing in a circular pattern. The bottom or floor of the room has not yet been reached, but there is again evidence of collapse in the form of fallen stones and big blocks of mudbrick. Very low in the room, at a depth of about 1m, but not associated with a floor, a bronze razor was found (Figure 10, FN22): it had been very carefully folded along with a small rectangular piece of bronze. Nearby was the upper part of a Base Ring jug (entire neck and part of shoulder, L89-P4, Figure 6). Even deeper, a stone basin was placed in the south-eastern part of the room. The basin has an internal diameter of about 0.40m, and is quite flat and shallow, with an internal depth of about 0.10m. The pottery at this level is mostly Plain White, with a few pithos, coarse ware, Base Ring ware, a sherd of a Minoan transport jar, and also includes a sherd of White Slip IIA ware (L92-P1, Figure 6), supporting a slightly earlier date for the earlier use of the room.

Room 107

West of R106 is R107, bounded by W17, W19, W20 and W23. The room has an interior surface that may once have included a plaster floor, but is preserved only as a hard surface with many limestone inclusions. The limits of the surface are clearly marked by white lines in the western and eastern part of the room (roughly 2.20 × 2.10m). The walls of the room are not very well preserved and are certainly disturbed and collapsed in several places. W17 and W23 are substantial walls of medium-sized and large stones with large corner stones at the ends. W19 is much disturbed, and W20 is partly in the western section and thus not fully exposed. The room has an entrance in the south-east, between W17 and W23, roughly 0.60m wide. This entrance appears to have been later blocked by the building of W18. Another grinding stone (L78-ST1) was found in this room.

The trenches south of T7 and T8, T7A and T8A, include some of the previously mentioned walls, but most of the area is covered in an extensive and quite dense collapse of large and very large stones. The excavations have not reached the bottom of this collapse, but it does seem to continue quite far down. Only in the most eastern and western parts are there small spaces with fewer stones or none at all. In the western section, a circle of medium-sized stones was associated with W21, and in the east, there is a small space just south of W16. In this latter space, against a large stone and the modern cement wall, an unusual three-legged Plain White pyxis was found, broken but nearly complete (Figure 7, L62-P1). The collapse of stones included many pieces of pithos and Plain White pottery sherds, along with grinding stones (L63-ST1, L63-ST2, L63-ST3, L63-ST4), a gaming stone (Figure 9, L88-ST1) and a small stone press (L88-ST2). The two latter were kept in situ. Many of the other stones removed from this have been cut or partially cut to be flat and angled, presumably for use in walls, and much of the collapse may thus come from previous walls. The pottery from this area includes the typical array of Plain White, pithos, coarse/cooking ware (including the flat base of a wheelmade cooking pot), White Painted Wheelmade and Base Ring ware. These indicate a mix of primarily LC IIC material with some LC IIIA, and may tentatively suggest a date for the collapse itself to LC IIIA.

The overall amounts of pottery are relatively low for a Late Bronze Age site on Cyprus (Figure 6), a total of c. 3100 sherds and complete or nearly complete vessels from the two campaigns. The most common types of ware are Plain White and pithos, especially of closed shapes related to storage and pouring/liquids. Notable finds include the three partially intact pithoi (large storage jars) excavated in T3, T4 and T6. In total, over 1000 sherds of pithos ware were collected. L20, the upper fill of the interior space of Room 101, contained a concentration of almost 40 Plain White sherds, including the restorable bottom half of a Plain White Wheelmade vessel (L20-P3). There are several additional examples of nearly complete vessels of Plain White ware, including the lower part of a closed vessel in situ in R104 (L60-P2), and most of an unusual three-legged basket handled pyxis (L62-P1) (Figure 7). A number of ceramic 'bathtubs' (deep oval basins) and wall brackets were also excavated.

Coarse/cooking ware also makes up a substantial portion of the ceramic assemblage, both handmade and wheelmade, and with both round-based and flat-based cooking pots. The cooking pot found in T7 (L37-P3, Figure 5) was complete, but too fractured and the fabric too friable to be restored. It was a wheelmade and flat-based vessel.

The smaller amounts of Cypriot-made fine wares include Base Ring, White Slip II and White Painted Wheelmade, including Aegean-type ware (also known as White Painted Wheelmade III from Åström's (1972) original typology). Various White Slip II sherds were excavated across the trenches, including examples of White Slip II Early (L11-P1), White Slip IIA (L16-P2), and White Slip II Late (L22-P2). Almost 100 sherds of Base Ring ware were excavated across all contexts, including examples of both Base Ring I and II. These fine wares indicate an LC IIC date for the site but there are some hints of slightly earlier material as well, such as WS IIA sherds. A continuation into LC IIIA is suggested by the cooking ware sherds, which include examples of flat-based and wheelmade vessels, and the Aegean-type skyphos with a monochrome interior (Figure 5).

Imports of Aegean and Levantine origin were collected across the trenches, including 37 sherds of various Mycenaean shapes. The chronology of the Mycenaean sherds suggests a date of LH IIIA2-B, and three Minoan body sherds of closed vessels (transport jars) date to LM IIIB, consistent with the overall LC IIC chronology of the site. Two Canaanite jar sherds can be added to the almost complete Canaanite transport jar found in R104 (L84-P2, Figure 7).

A substantial number of groundstone tools have been found, appearing in almost all trenches, testifying to agriculturally related activities (Figure 8). Many may have been left behind because they, although movable, are quite heavy, and easily replaced at a new site. Many are also broken. The majority are made of a dark grey-greenish stone, probably basalt or diabase. A total of 22 grinding slabs were found, all of small to medium size. All but four were broken, and the four complete specimens range in size from 14.2 to 34cm in greatest length. Another eight handstones (grinders/pounders, pestle) were found, mostly in the northern trenches. The grinders/pounders are mostly bun-shaped or discoid with one or two faces. Presumably these tools were used for grinding cereals, although they could also have been used to grind other plants or minerals.

Other stone tools relate to production and industry. Part of a tripod stone mortar (W12-ST1, Figure 12C) had been reused in the construction of W12. It is of a type usually associated with the Levant and frequently found at sites in the Syro-Levantine region (Yon 1991; Bretschneider et al. 2017, 84-85). A small stone press, c. 26cm in diameter, constitutes another type of stone tool (L88-ST2). It is very shallow and with a spout as the drain. Although small, it may have been used in the process of olive oil production. It is part of the collapse in T7A and has been left in situ. Stone rim fragment FN12 may have belonged to a basin, mortar or press. Finally, the complete stone basin in R106 may have been used in industrial activities involving liquids.

Four so-called gaming stones were found during the 2023 campaign (Figure 9). One was a surface find (surface-ST1), one was in R105 (L83-ST1), and one in the collapse of L88 in T7A/T8A (L88-ST1, left in situ). Most remarkable is the large one found upside down below two plaster floors in R101 (L75-ST2). The level of preservation varies, but they all have the typical three rows of small 'cups'; the large example has additional, bigger indentations. A fifth gaming stone was reused as part of W5 (still in situ in the wall, Figure 12C).

Picrolite is not a commonly used raw material in the Late Bronze Age on Cyprus, especially in comparison with earlier periods. However, given the nearby sources of the Kouris River and Troodos Mountains, it should perhaps come as no surprise that a few picrolite objects occur at Pitharka. Three small picrolite items have been found so far. A bead, a 'button' (3D model 2), and a finger ring (Figure 10). The bead is slightly conical, with a height of 19mm and an 8mm-wide piercing (FN3). The function of the enigmatic 'button' is not clear (FN2). It has a height of 10mm and a diameter of 16mm; it is a conical shape with a rounded top, and on careful inspection prompted by the rendered 3D model, it can be seen that the sides are slightly flattened. Its bottom has a number of engraved or scratched lines. These lines could suggest a function as a seal, but they appear rather random, and the surface is very slightly concave. Another suggestion is that it is an inlay, perhaps once attached to a textile, a vessel, or as the inset of a ring (with the scratched lines acting to aid adhesion).

The third picrolite object is perhaps also the most remarkable one. In the blocked entrance to R101, a unique picrolite ring was found (FN21). The ring is complete and slightly worn but well preserved. The head of the ring has a slightly flattened part with a design of two semi-circles next to each other and with a central dot in each. While other pieces of picrolite jewellery are well known from Cyprus (especially beads and pendants), we have not been able to find close parallels for this engraved ring.

Only three metal objects have been found in the new excavations (Figure 5, Figure 10), although some were found in the previous excavations, including a ploughshare (Papanikolaou 2012, fig. 6). This probably reflects the time available for the inhabitants to leave the site, rather than the actual use of metal tools and other objects. The first object is the bronze needle that had been placed inside two vessels (FN16), in the corridor in T7. It is intact, and has a length of 70mm. The second is another pin or needle (FN19) that is 59mm long; this was found in R101. Unlike FN16, this example does not have an eye preserved. It is possible that this has broken off, but there is no longer a visible break. The third object is the bronze razor found in R106 (FN22). It is somewhat eroded, but otherwise quite well preserved, and appears to be complete. It was folded in on itself along with a small rectangular piece of bronze, presumably a deliberate action to remove the object from use. Its unfolded length is 182mm.

After two seasons, we can now determine that the archaeological layers at Pitharka are significantly deeper in some parts of the site than first expected. Whereas much of the area excavated during the first season exposed only fairly shallow remains, with the limestone-like bedrock about 0.30-0.40m below the current surface level, the structures in the north-western part of Area 1A are at least 1.40m deep in some rooms. The first foundation of these rooms and the bottom of their associated walls may be even deeper than this. Owing to the well-preserved floor in R101 and the stone basin in R106, we have chosen to keep these contexts as they are rather than remove them in order to determine the exact wall depth; we estimate that this will instead be possible in other rooms in the future. These deeper walls and rooms reveal not only that the bedrock was exploited and cut into to make interior semi-subterranean spaces, but also the presence of several phases at the site.

At least two architectural phases can be identified so far in some areas, as is most explicitly expressed with the change in the arrangement of the earlier Rooms 106 and 107 (Figure 11a) to the later Rooms 102 and 103 (Figure 11B).

A sequence of construction, rearrangement and collapse/abandonment can also be reconstructed for R101 and its surroundings. In its earliest use (as excavated), it was limited by W5, W7 and W11, with an entrance in the north-west, and the plaster floor had a ridge and was curved against the walls. The room was then subsequently divided along the line of the ridge, and two installations were added: a mudbrick one against W11, and the 'pile' of medium-sized stones (including reused grinding stones) against W5. These were associated with a sequence of two plaster floors on top of the large upside-down gaming stone. It may be at this stage that the entrance in the north-western corner was blocked by the construction of W16, but this could also have occurred later. The entire northern part of the room then burnt, possibly ignited by the activities related to the installations, although a deliberate fire cannot be ruled out, since objects such as the pithos appear to have been thrown into the room. Finally, the fire likely caused the extensive collapse of stones and mudbrick that characterises the upper loci of the room.

The walls of R101 also suggest a stage of habitation that is even earlier. While there is evidence of reuse, reinforcement and repair of walls elsewhere, there is no indication of this for W11 and the northern part of W5, both of which reuse objects that must originally have been placed and used elsewhere. In W5, a gaming stone had been incorporated into the uppermost preserved course of the wall, and in W11, a pivot stone was similarly used, not near a doorway, but almost in the centre of the wall (Figure 12A and 12B). This type of reuse is common at Late Bronze Age sites on Cyprus, and we also see it in W12, where a broken stone mortar (W12-ST1) and a broken grinding stone form part of the wall (Figure 12C).

In other cases, we can see that walls have been extended, added to, partly reused and sometimes greatly disturbed at various points. So far, these activities seem to all occur primarily within the LC IIC period, based on the associated pottery. Although we can reconstruct a more complex sequence of use and arrangement in R101, R102/R103 and R106/R107, it has not been possible to determine a more precise time frame or time between the changes, beyond an overall LC IIC horizon. The widespread collapse of stone and mudbrick walls may tentatively be suggested to belong to LC IIIA.

The rooms uncovered during the new excavations in Area 1A constitute a sector of a large building complex that continues from Area I, previously excavated by the Department of Antiquities (within the modern concrete wall). The connection is clearly demonstrated by the continuation of Room 7 from Area I to Area 1A in T1 (eastern trenches), and strongly suggested by the walls of R101 (northern trenches) continuing below the modern cement wall. The entirety of the complex and its exact limits still need to be determined, which is one of the main aims of future campaigns. Nevertheless, it is already clear that it was a substantial complex, and that it is unlikely that habitation was its main or even secondary function. It consists of a series of connected interior and exterior spaces. The interior spaces include Room 7, R101, R102, R103, R104, R105, R106 and R107 (Figure 2B, Figure 11A-B), with additional rooms only partly excavated in the eastern trenches extending further to the east and north. The rooms were connected through entrances, corridors, and with exterior areas and open or semi-open areas, with surfaces of small rubble or pebbles, or the artificially levelled bedrock.

The rooms have generally been constructed of sturdy and well-built walls that were initially made with quite large and often cut stones, sometimes with later additions of smaller and less carefully placed stones. The walls are typically 0.60-0.80m wide and with a depth of up to 1.40m, although some instead utilise the bedrock in the lower parts, as is the case with, for example, W5 and W7; for W2, this was combined with a mudbrick-based levelling. As mentioned above, there is much repair, reuse and sometimes even removal of parts of walls in the uppermost loci. For example, the western part of W19 tilts slightly to the south, and had been reinforced with a row of stones, presumably associated with the rearrangement of the space that became R103. On the other hand, W17 had been almost entirely removed, and it is likely there was also once a wall south of and parallel with W14, the stones of which may have been reused for other walls or blocking.

The structures uncovered so far are assocoiated with pottery, but not the amount that might be expected or seen elsewhere at Late Bronze Age sites on Cyprus. So far animal bones are almost entirely absent. In total, there is only a handful of animal bones from the two campaigns (sheep/goat teeth and a few medium-sized metapodia), few of which are from secure contexts. A single shell (Tritia gibbosula) was found in T7 L60 (identified by M. Yamasaki and D. Reese). It seems that the entire area was peacefully abandoned: most light movable material has been cleared out, while heavier and/or broken objects such as pithoi, bathtubs and worked stones were left behind. For the moment, we see no evidence of destruction (violent or otherwise) apart from the interior burning in the northern part of R101. Given this clearance, it is challenging to determine the function of each individual space, but we nevertheless gain an overall understanding of the use of the complex based on the structures, features and material culture left behind.

These indicate a focus on industry and storage related to liquids and agricultural products. The high percentages of pithos fragments found in all the layers so far excavated (and after which the site receives its name) reflect the significant storage capacity of the site. Preliminary analysis of the ceramic assemblage indicates that pithos sherds constitute about a third of the pottery recovered so far. Although recent studies demonstrate that a limited number of pithoi did travel from their place of manufacture (Pilides 2000, 110-12; Porta and Cannavò 2023), these jars are by their nature large and heavy objects used for storing produce and as part of industrial processes of production. They are found at nearly every excavated Late Bronze Age site on Cyprus. An impressive collection comes from Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios, contemporary with Pitharka (LC IIC) and about 35km to the east. There, Building X contained nearly 40 large pithoi with a total estimated capacity of 35,000 litres (South 1989, 321; see also Keswani 1989). Within the Kouris Valley, Alassa is the regional settlement with which Pitharka is likely to have had the closest connections, where a range of pithos shapes and sizes has been identified, with cautious volumetric estimates between 250 and 1000 litres for individual containers (Keswani 2017). The exact sizes and typology of the Pitharka pithoi need further study, but the most intact example from Trench 3 suggests capacities of up to at least 300 litres. The other nearly intact example from R101 is much smaller, reflecting the variety of large vessels used, presumably for different stages of production and types of storage.

Pithoi are usually believed to have contained cereals, olive oil, wine or water. Archaeometric analyses are yet to provide solid confirmation of this, although results from sherds from Alassa tentatively support the presence of wine in pithoi from the site (Keswani 2017, 380-81), while analysis of sherds of the Kalavasos-Ayios Dhimitrios pithoi suggests olive oil (South 1991, 132). From Pitharka, the very preliminary finds of archaeobotanical remains from flotation samples further support this, with possible finds of grape seeds and olive pits, but this needs confirmation through systematic analysis which is currently being carried out. Modern ethnographic work on the use of pithoi on Cyprus also primarily provides examples from wine production (London 2020, 44-45; see also Pilides 2000, 103-5), but other uses include dry storage, storage of water or olive oil and as a bathtub. Large pithoi can still be seen today scattered around the villages especially in the Troodos mountains, and wineries often display them as part of the traditional processes of wine making.

In her work, Keswani has identified three major groups of pithoi for Late Bronze Age Cyprus, based on their size, wall thickness and type of neck and opening (Keswani 1989). Based on these, she suggests functions related to daily or regular use of contents (easy access through a wide opening and shorter necks, usually smaller sizes) and long-term storage where regular access was not needed (more restricted opening, longer necks). The preliminary work on the Pitharka ceramics finds all three categories present, again emphasising the variety of vessels. Once installed or placed in their intended location, pithoi are not easily moved - even less so when filled. Even the smaller versions would likely require collaboration between several people and/or rolling the pithos on its side. Once placed, they are thus unlikely to have been moved.

Another large type of container used in production is the so-called 'bathtub'. These vessels were almost certainly not actually used as bathtubs, but have been given this label owing to their resemblance to modern bathtubs: they are deep basins, often oval or rectangular with rounded corners, frequently with an opening in the lower body near the long, flat base. Their open shape and opening suggest that they were not storage vessels, and that their use is related to some sort of liquid. Bathtubs are typically made with the same clay, tempering and thickness as pithoi, and smaller sherds can be difficult to distinguish. Nevertheless, their presence and use at Pitharka is confirmed by both sherds and more complete vessels. This includes the example found in F4, where about half the base and lower part of a bathtub, including the part with the opening near the base, were found in association with pithos sherds and a stone-built structure. A complete bathtub was also found in the previous excavations at Pitharka as part of an installation (Papanikolaou 2012, fig. 4), now on display in Limassol Archaeological Museum. Beyond the pithoi and bathtubs, roughly another third of the ceramic assemblage from Pitharka comes from plain ware vessels. Many of these are closed vessels, jars and jugs, that may also have played a role in manufacture, although such vessels can be highly multifunctional.

The role of liquids at Pitharka is further indicated by the drain in T2, which may have been part of a water management system or related to production (a similar drain was found previously in Area I, running below a wall (Papanikolaou 2012, fig. 2). The lowest floor of R101, with its carefully plastered surface, curve along the walls, and deliberate ridge in the centre, was likely used in liquid-related industries, as was the stone press, and possibly the stone basin in R106. The stone press and several fragments of low-walled stone basins are comparable to the equipment known from olive crushing/pressing from Late Bronze Age Cyprus (Hadjisavvas 1992). That the production also included cereal processing is demonstrated by the many groundstone tools. Although grinding of other material may also have occurred, the grinding slabs and handstones are typical of those used to grind cereals to fine flour. The number of such tools found in the relatively limited space of Area 1A to date hints at the importance of such tools.

Pitharka's role appears to have been primarily regional, producing and possibly supplying or redistributing goods to the contemporaneous sites in the Kouris Valley. Permanent installations like F4, with its bathtub and pithos fragments, the pithos placed into a custom-made cut in T3, and the pit in T5 demonstrate that storage and production was literally built into the fabric of the complex, as does the semi-subterranean character of the rooms. The nearly complete absence of faunal remains and very limited evidence of textile-related activities (one complete and one broken loomweight) in Area 1A mean that we can at present rule out a strong focus on industries related to animal or animal-derived produce, at least in that area. Instead, the arrangement of the spaces (including sunken architecture), installations related to liquid and storage, objects associated with cereal and olive oil/wine production (groundstone tools, stone press) lead us to tentatively suggest a focus on cereal, wine and olive oil production and storage at Pitharka.

The regional character of these aspects is reflected in Pitharka's engagement in the system of long-distance interactions that are typical of the Late Bronze Age. In contrast to contemporary coastal or near-coastal sites such as Hala Sultan Tekke, Enkomi, Maa-Palaiokastro and Pyla-Kokkinokremos, which are marked by a proliferation of imported (luxury) goods, imports from the Aegean and the Levant are present at Pitharka but they are limited in variety both in shape and material.

There is much evidence of collapse throughout the area, with many fallen stones and much decayed mudbrick material fallen into rooms, often in the vicinity of the walls where they came from. However, there is little other evidence of destruction and, in general, the rooms are comparatively empty, with what was left behind being mainly large or heavy objects, such as stone tools and pithoi. This indicates that Pitharka was abandoned fairly peacefully or, at the very least, that its inhabitants had ample time to leave the settlement and take their belongings with them.

There are tantalising hints of deliberate abandonment practices. For example, some areas of collapse are particularly dense, with large stones placed vertically, blocking entrances and the corridor in T7. The cause of the fire in R101 is not known, but the presence of the partial pithos seemingly thrown into the room is somewhat curious. Similar practices have been documented at Middle Cypriot Erimi-Laonin tou Porakou, where material culture was collected in selected spaces and then burnt (Amadio and Bombardieri 2019), and it has been argued that an even longer tradition can be traced back to at least the Chalcolithic (Düring 2023). The deposition of the two vessels placed against each other with an intact needle inside on top of the collapse, also indicates deliberate action associated with the abandonment of this part of the site. The two vessels fit best in an LC IIIA chronology, and may thus provide a date for the collapse, or at least this particular deposition.

The inhabitants may not have moved far, as it seems that other parts of the site continued in use for slightly longer. For example, the cave north of Area I/1A contained pottery dated to LC IIIA-B (Vassiliou and Stylianou 2004).

The Area I/1A building complex is clearly quite large (with a current estimate of c. 2000m²), but excavations have not yet identified its exact limits, nor have the deepest foundations been uncovered. Future excavations will focus on precisely these aspects, following the extent of already partially uncovered spaces, and solidifying the connections with the earlier excavations. This is to further establish the types of agricultural production activities taking place at the site and their architectural contexts. Another important aspect of this will be the results of ongoing and additional analyses of ceramic and lithic material (starch granule analysis, organic residue analysis, petrography) and soil samples (archaeobotany, phytoliths) to gain more information about the products present.

We are grateful to the director of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus, Marina Solomidou-Ieronymidou, for granting permission to excavate at Erimi-Pitharka. We would also like to thank Katerina Papanikolaou, Demetra Aristotelous (Limassol Museum) and Evie Thrasivoulou (Episkopi Museum) for their help in making the excavation possible, Luca Bombardieri, Marialucia Amadio, Giulia Muti and Andrea Villani for help during the 2022 campaign, and Artemis Georgiou, Peter Fischer, Gabriele Koiner, Manfred Lehner and Peter Scherrer for general advice. The preliminary ceramic analysis was carried out by Brigid Clark and Lorenzo Mazzotta.

The 2022 field team of Natalia Ciuchta, Brigid Clark, Lukas Gran, Panagiotis Koullouros, Maria Papapaschou, Julia Preininger, Magdalena Rejmer, Marina Schutti, Fabian Welc, Tobias Welz and Mariusz Wiśniewski and the 2023 field team of Brigid Clark, Lukas Gran, Panagiotis Koullouros, Julia Preininger, Carl Sanfilipo, Azra Say-Otun, Marina Schutti, Mari Yamasaki and Tobias Welz are also thanked.

The project is funded by the University of Graz (Institute of Classics and Office of International Relations), with additional support from Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University, Warsaw, National Science Centre Poland (GPR survey, Miniatura 6 grant no. 2022/06/X/HS3/00089, Katarzyna Zeman-Wiśniewska), and Marie-Skłodowska Curie (Cofund Polonez Bis, grant no. 2021/43/P/HS3/01355, Mari Yamasaki/UnReal).

The data used to support the findings of this study are wholly included within the article.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.