Cite this as: Aagaard, J.R., Hjulmand Larsen, C., Bødstrup Christoffersen, J.E., Munch Thomsen, J., Birk, K., Kaas, M.H., Fur, R., Termansen, S.S. and Dobat, A.S. 2025 Metal detecting in university education: Empowering future archaeologists through training, Internet Archaeology 68. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.68.1

Metal detecting has emerged as a valuable tool in the field of archaeology. The significance of this field is, however, not adequately reflected in university curricula. Therefore, this article delves into the possibility and impact of incorporating metal detector archaeology as a standard practice in university education, empowering future archaeologists with essential training. Avocational metal detecting, a crucial tool in archaeology, reveals artefacts and offers insights into our shared past. At the same time, in some countries, metal detecting is considered a heritage crime, and the phenomenon is therefore a contentious concern in many countries. Irresponsible practitioners can inflict enormous damage to archaeological sites and assemblages in their search for artefacts, either for their own personal collections or for private sale (Dobat 2013). Despite its significance and impact, metal detecting rarely features or is prioritised in university contexts or curricula. By integrating the practice into the curricula, students acquire a set of skills and competencies within but also beyond the narrow field of metal detector archaeology; fieldwork techniques, finds registration, data management, artefact analysis and an understanding of collecting and hobbyist communities. This will further prepare the students for collaborative work between professionals and hobbyists to preserve and interpret our shared human history.

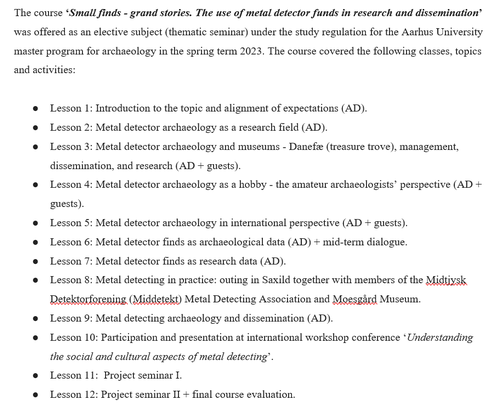

In Denmark, metal detecting is a legal pursuit, and it has developed into a popular hobby with a growing number of practitioners, the majority of which can be defined as enthusiastic and highly committed (Dobat and Jensen 2016). Consequently, it constitutes a significant element of professional archaeologists' work - both today and in the future. Given this, it was natural (and quite uncontroversial) for the department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies at Aarhus University to offer a 10 ECTS (European Credit Transfer System) master level course in the spring term 2023, focusing on the phenomenon of avocational metal detecting. Grounded in the experiences and insights gained from a course titled: 'Small finds - grand stories. The use of metal detector finds in research and dissemination', with Andres Dobat as principal coordinator and teacher, this article aims to go beyond a purely theoretical discussion. Instead, this article seeks to offer first-hand 'lessons learned experience' to advocate for the integration of metal detecting into university curricula. While also providing insightful perspectives and innovative ideas, the article can serve as a practical guide, influencing and actively shaping similar courses. With a focus on advancing the education of future archaeologists in the realm of citizen science and metal detecting, the article functions as an example for educational curricula, highlighting the university's pivotal role in this specific field.

This article delves into our individual experiences, shedding light on the varied outcomes and challenges encountered. The structure of the article mirrors the structured lesson plan (illustrated in Figure 1) and corresponds with the progression of the course. The course culminated in offering an opportunity for the students to engage and participate in a workshop conference, serving as the precursor for the content discussed here. It is therefore important to note that even though Andres Dobat is a co-author, this article centres on the perspective of the students enrolled in the course.

'It was created by the devil'; is the title of one of the first articles in Denmark to address the topic of metal detecting. Fears regarding inadequate recording of finds, outright theft, and the destruction of archaeological contexts were all concerns brought to the surface in the wake of the growing hobby (Fischer 1983). Instead of creating a ban on metal detecting (as seen in other countries), the National Museum of Denmark and the Danish Heritage Agency produced a pamphlet that set out some guidelines, which drew attention to the legislation and encouraged people to cooperate (Petersen 2016). Consequently, Denmark has had a liberal model based on cooperation and inclusion rather than confrontation and criminalisation. Most Danish archaeologists today would probably consider the metal detector, as well as the metal detecting hobbyist community, to be an indispensable tool for archaeology (Henriksen 1998).

In addition to the contribution made by metal detectorists who have reportes tens of thousands of objects and identified new archaeological sites over the last three decades, the metal detecting community has provided important new sources for the study of art, style, production techniques and trade (Feveile 2018). Furthermore, the metal detecting community has also prevented many endangered archaeological artefacts from being destroyed in the ground as a result of modern agriculture (Henriksen 2006).

Legally, metal detecting in Denmark is based on a finds confiscation system, stipulated in the Danish Consolidated Act in Museums Chapter 9 ('Danefæ') (Kulturministeriet 2014). The law prescribes that a treasure trove reward is paid to finders, the sum being assessed by the National Museum, taking into account the objects' cultural historical value and material value (for the Danish treasure trove system see: Nationalmuseet n.d.). In 2021, the National Museum of Denmark received 30,633 finds that had been submitted by local museums for Danefæ processing (Nationalmuseet 2021). This is an extremely high figure, which indicates that the necessary time for processing and registration is increasing as well. It is in the wake of the substantial increase in detector finds that Digitale Metaldetektorfund (DIME) was created in 2016, with the hopes of simplifying and expediting the recording process and administrative handling of detector finds in Danish museums. DIME aims at making detector finds and their information accessible to the general public and researchers (Dobat et al. 2020). Unlike the British Museums Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS), DIME, relies entirely on finder's records and is based on the philosophies underlying citizen science (Dobat and Jensen 2016). Archaeologists at Danish local museums do not record the finds in DIME but merely verify, edit or complete finders' records. In PAS, professional Finds Liaisons Officers (FLOs) record and describe all relevant finds, providing qualitatively strong records in England and Wales, while DIME has the advantage of quantitatively strong records in Denmark (Gill 2010). This approach to discovering finds has also brought new research perspectives based solely on detector finds, which would not have been possible without the people who dedicate a great amount of their personal time to using a metal detector (Kaas and Grundvad 2022). Thanks to DIME, amateur archaeologists are becoming so competent that they themselves are becoming involved in the finds research (Holst et al. 2023). For a summarising overview of metal detecting in Denmark, see Dobat (2016) from a research perspective, for a museum perspective, see Baastrup and Feveile (2013) and from the perspective of detectorists, see Kjær (2021).

The opinions and attitudes of archaeologists towards (and against) hobby metal detecting are diverse. Legal and policy approaches differ greatly across jurisdictions, ranging from liberal and even supportive (as in Denmark) to highly restrictive, and many shades in between. The plunder of heritage sites by illegal or irresponsible detectorists in search of artefacts for their own personal collections or for sale is an enormous issue in many countries, notably around the Mediterranean or in Eastern Europe (Ganciu 2018; Lecroere 2016). Although the level of discussion surrounding it certainly varies between countries and individuals, one thing seems constant: metal detecting is hardly, if ever, part of the university courses that train the next generation of archaeologists. Instead, this cooperation is formed out of necessity when the archaeologists encounter metal detecting in their everyday work at museums or other administrative institutions.

The Danish experience of liberal metal detecting regulation shows that inclusion and cooperation with the detecting community contributes to the safeguarding and preservation of the archaeological record and may be much more rewarding than restrictive approaches aiming at the control or even prohibition of metal detecting (Dobat et al. 2019 ; 2020 ; Dobat and Jensen 2016). Exchanging data and knowledge on this level allows not only for a larger base of knowledge, but also furthers trust between the institutions and individuals, and makes the detectorists more likely to hand over their finds and generate thorough and detailed records (Dobat et al. 2019). Users take pride in what they do, which leads to a form of self-policing, and guiding other detectorists and keeping rule-breakers in line becomes a natural part of the detecting community, leading to a higher standard of field practice and finds data.

Whether metal detecting as a form of public participation in archaeology can be regarded as a positive contribution to the field is a debated topic (Dobat et al. 2020). Metal detecting is, however, becoming a very prominent part of archaeology. In Denmark as well as in England and Wales, the volume of metal finds and associated surface finds of other materials continues to skyrocket (Dobat and Jensen 2016). This consistently changes established interpretations of for example Iron Age and Medieval settlement landscapes (e.g. Bondeson and Bondesson 2020 ; Lykkegård-Maes and Dobat 2022). The growing importance is reflected in new museum strategies that embrace the detectorists as partners (Lewis 2016), reaching out to form mutually beneficial relationships, resulting in both excavation and research collaborations. And yet, this aspect of archaeology is vastly under-represented in the average selection of university courses. If the metal detecting hobby is growing in popularity and intensity as much as current statistics suggest (Dobat and Jensen 2016 , 71; Lewis 2016 , 129-30), then many new archaeologists will be under-equipped to make full use of the resources presented by this field, and to interact with the community in an appropriate manner.

While the lines between professional archaeologists and amateur archaeologists are blurred in the Danish Museum realm e.g. through volunteer work, citizen science contributions and hires from outside the field, the separation between the two categories remains. This distinction between 'professionals' and 'amateurs' suggests a power imbalance (Taylor 1995 , 500-2), where the amateurs must conform to being invited into the professional space, and the professionals remain the authority on procedures. This becomes evident in how finds are managed (both at local and national museum level), in management of databases, in the rules and guidelines for detectorists, as well as in courses arranged by or in collaboration with local museums, established to educate detectorists on the desired standard or customs used by archaeologists.

Detector users in Denmark do take the initiatives in educating themselves in this field (Kjær 2021), and while the above-mentioned proposals are by no means a bad thing, and do indeed help to strengthen collaboration between museums and detectorists, it does beg the question: Should archaeologists educate themselves in the same way we expect detector users to be educated? If detectorists must adjust to the professional standard and communication of archaeologists, why don't archaeologists, in all levels of the system, make an equal effort to understand the detecting community, its pitfalls, challenges, and potential?

By introducing metal detecting as part of new archaeologists' training, an element of fairness and balance is added to this relationship, which could prove crucial in maintaining and improving it. Furthermore, it allows researchers who might never have direct contact with the detectorists themselves, but work with detecting finds, to take an informed and critical approach to the material, knowing what challenges detectorists face in the field, and how this affects the data.

It is simply a matter of preparing archaeologists to handle a part of their field that will only become more prominent in the years to come — and to embrace this change in a way that yields the best possible outcome for detectorists, archaeologists, and future research.

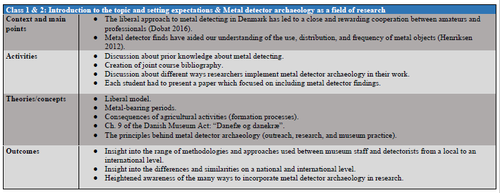

The course 'Small finds — grand stories. The use of metal detector finds in research and dissemination' was offered by the Department for Archaeology and Heritage Studies at Aarhus University in the spring term 2023. The course was offered as a masters level seminar and Figure 2 provides an overview over the different classes and their contents.

The oral examination, lasting for 30 minutes, provided students with a platform to engage in scholarly discourse and showcase their understanding of metal detecting archaeology. This assessment format, inclusive of discussion and grading, was underpinned by synopses submitted by students prior to the examination, delineating their chosen topics and areas of inquiry. The examination framework, meticulously crafted to offer students a considerable degree of flexibility and autonomy, was designed to encourage independent thought and creativity. It provided a broad platform that allowed students to delve into various topics within the realm of metal detecting archaeology. Rather than imposing rigid guidelines or limiting the scope of inquiry, the framework empowered students to explore and interpret the subject matter in their own unique ways. This open-ended approach gave students the liberty to write about whatever aspect of metal detecting archaeology they found most compelling, and each student was encouraged to bring their own perspective and critical insights to their work, making the examination not just a test of knowledge, but also a reflection of their individual intellectual curiosities and interpretive skills. This freedom fostered a rich diversity of responses, as students were able to tailor their projects to align with their unique academic strengths, interests, and views on the discipline. Some of the themes presented and discussed by the students in their examination assignments are listed below.

The oral examination functioned as a comprehensive culminating assessment that not only determined students' depth of understanding in the field of metal detecting archaeology, but also created a platform for intellectual discourse.

Seen through a university teacher's lens, a topical course on the many different facets of metal detecting was both timely and relevant. Timely because the phenomenon is still 'a big thing' and it will probably only grow in popularity, globally and for many years to come. Future heritage professionals therefore need to be prepared and get acquainted with both the challenges and the potential arising from this trend. Relevant not least because metal detecting can be used as a framework to acquire transferable knowledge and skills that may be useful in the future for those working in the wider field of archaeology.

In a wider social and theoretical perspective, the course was timely, not least in light of the growing demand to be conscious of our profession's social context. This is particularly relevant in Danish archaeology, which traditionally is deeply rooted in cultural historical and processual paradigms, while post-processual concepts and multivocal, democratic and egalitarian approaches have had only a limited impact on archaeological practice (with some exceptions). The idea that, whether you like it or not, archaeologists share the archaeological record and the past with other members of society who want to engage with it, is an important topic for any future practitioner. Discussing metal detecting and the cooperative model practised by the Danish museum sector hence also becomes a methodological 'sandbox' for developing an understanding of different approaches to public archaeology and inclusive/democratic approaches in heritage management, where management automatically merges with research and outreach/dissemination.

Metal detecting has become a popular topic in popular culture and media. Topical magazines (e.g. Treasure Hunting published in Britain) or even TV-shows (e.g. the BBC production Detectorists or the Danish edutainment show Muldens Mysterier) tap into the fascination and excitement many connect with the discovery of historic treasures. In Denmark, metal detecting (both the artefacts and the ever-fascinating stories of discovery and adventure) has become a central element of museums' promotional strategy. Detectorists also take on an active role in the dissemination of their hobby, be it through the national association of hobby archaeologists' publications, individual initiatives on social media or in cooperation with museums and national media (e.g. Kjær 2021 ; Klæsøe 2020). In retrospect, we did not adequately cover this important dimension of the metal detector phenomenon in Denmark. A redesign of the course would, therefore, contain a dedicated class in which students were supposed to explore different forms and types of dissemination relating to metal detecting, producing a catalogue of ideas and best practice advice for museum professionals.

In the end, metal detecting is about artefacts, their context and what they can tell us about the past, and the course made us revisit important elements of the basic archaeological toolset, such as artefact description, dating, typology, etc. If I were to teach the course once more, I probably would start out from a more basic and more practical approach, bringing to the table selected finds and asking the students to perform a finds-recording process (e.g. in the DIME platform), transforming physical objects into digital research resources. Many students did pick up on the potential of metal detected finds as research data in their examination papers. However, in a second version of the course, I probably would have facilitated a more focused discussion on possible approaches to metal detected find assemblages as research resources e.g. different avenues of research, whether settlement landscapes, network studies, or social/cultural identities for example.

It was a very specific factor (and to some degree just a lucky coincidence) that the course could be offered simultaneously with the funding period of the NOS-HS funded workshop series 'From Treasure Hunters to Citizen Scientists', culminating in the Aarhus Workshop. These two factors allowed me as a teacher to put action behind the ideal of 'research-based teaching' which is central to Danish university curricula. First and foremost, however, it gave me the rare opportunity to let students have a real taste of an academic workshop/conference. In terms of content and as a didactical framework, running the course was not conditional on the workshop conference.

Reflecting on the outcome of the course as a pilot and possible source of inspiration, it is central to note that the course 'Small finds — grand stories: The use of metal detector finds in research and dissemination' naturally was situated in a specific context. There can be little doubt that the students were biased in their perspective on the phenomenon, given the relative success of avocational metal detecting in Denmark and the very positive (rosy) light that public media and professionals alike portray the pastime. This could be seen as limiting the wider applicability of the course and renders it difficult to simply copy-paste its program and contents into another national setting, where detecting cultures and professional attitudes may differ significantly.

No matter the context and which narratives and attitudes towards metal detecting are prevailing in any given national or cultural setting, the above might still serve as a source of inspiration for colleagues to include aspects of metal detecting (including, but also beyond, its unfortunate face of heritage crime) into archaeology programs in the future.

As we approach the culmination of our master's studies in archaeology, we are on the verge of entering museum environments where collaboration with metal detector users is not just expected but fundamental to the essence of modern archaeological exploration. Against the backdrop of Denmark's archaeological landscape, reshaped by the transformative influence of liberal models, a course dedicated to metal detecting archaeology emerges as a natural progression. It reflects a paradigm shift in archaeological practice, where collaboration with metal detector enthusiasts assumes increasing prominence within the institutional framework at museums. But what did we learn, regarding the various aspects of the phenomenon in Denmark, internationally and beyond? Trying to put our learning outcome into a nutshell in the form of take-home messages, the following is what we gained from attending the course:

The two most surprising outcomes of the course that made us look at archaeology in a different way are:

The two most important lessons we learned for our future professional careers as archaeologists working in the Danish Museum sector were:

1. Hobby detectorists are a boon to archaeologists at museums; their time and effort is extremely valuable. The majority of amateur archaeologists work with a level of professionalism rarely seen elsewhere.

2. We are lucky to have such a well-working cooperation in Denmark, and that luck should not be taken for granted. Continued success hinges on continued effort.

The two most important lessons we learned for our future professional careers, be it within or outside archaeology are:

It is imperative to underscore that while the aforementioned insights learned from the course are invaluable, it is equally crucial to acknowledge that many students possess diverse interests beyond the realm of metal detecting. In the event of a course reiteration, a broader perspective would be welcomed, one that encompasses citizen science and public archaeology in its entirety. Such an approach would afford students the opportunity to explore the broader implications of these disciplines on their respective areas of specialisation within archaeology, thereby fostering a more holistic understanding of their field-specific interests.

While any university class is dependent on local factors and logistics such as availability of lecturers, timing, extent of class etc. that would make directly transferring one course curriculum to another challenging — a course on metal detector archaeology has, it could be argued, the added challenge of fitting within the legal and institutional frameworks of the country in which the course would take place. The work done within this specific course may not be directly transferable to another setting; however, elements such as the curriculum, lecture themes and our experiences can serve as an inspiration to future endeavours of this kind. The applicability of overarching themes such as citizen science, international and cross-border collaboration and — provided that sufficient data are recorded — big data research can hardly be overstated. Metal detector archaeology can serve as a lens through which one can examine the field of archaeology, and there are important lessons to be learnt from the detecting community.

Perhaps even more importantly, metal detector archaeology is here to stay. It is a hobby with a growing user base; the amount of detector finds is steadily increasing year by year (e.g. Dobat 2013 ; Dobat and Jensen 2016 ; Lykkegård-Maes and Dobat 2022), and with the development of large national databases e.g. the Danish 'DIME', Portable Antiquities of the Netherlands 'PAN'' and Portable Antiquities Scheme 'PAS'' (Dobat et al. 2019 ; Wessman et al. 2023), comes the potential for research. Often the focus of teaching detector archaeology falls on educating hobbyists on legal and methodological factors, but there is a marked hubris in not recognising the necessity of educating archaeologists as well. It is our responsibility as professionals to ensure that we stay educated, and we would certainly argue that this requires staying up to date on a subfield whose importance in archaeology has been growing exponentially for decades. Simply put, archaeological education should cover metal detector archaeology, as it plays too considerable a role in our field to ignore.

The authors would like to thank several people and institutions, including Moesgaard Museum, guest lecturers, Tony Bülow (detectorist) and Daniel Dalicsek, who all contributed to the students' learning outcome and in facilitating the different interesting aspects in the course.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.