Cite this as: Kurisoo, T. and Smirnova, M. 2025 Unearthing Perspectives: Exploring the views of heritage professionals and hobbyists on the current state of metal detecting in Estonia, Internet Archaeology 68. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.68.3

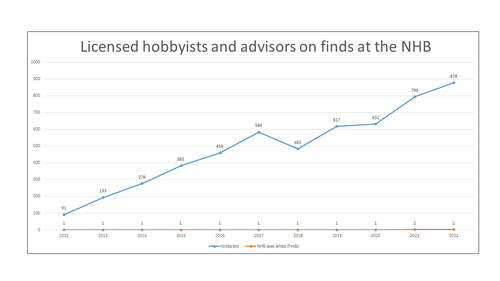

The hobbyist metal detecting of archaeological finds has been regulated in Estonia for more than a decade. First there was an amendment to the Heritage Conservation Act (HCA) in 2011, and subsequently a new version of the HCA came into force in 2019, which specified the rules for hobby metal detecting. The legislation describes the rights and responsibilities of hobbyists and the state, represented by the National Heritage Board of Estonia (NHB). In Estonia, all archaeological finds belong to the state and finders are entitled to a reward. The reward depends on the cultural value of the find, as well as the circumstances in which it was found and handed over to the state. Freelance small finds experts help to determine the cultural value by assessing the artefacts and their possible contexts (in the form of an expert opinion), which provide the basis for further decisions. Searching for archaeological finds as a hobby requires a licence, which can be obtained after passing a specific training course. Metal detectorists need permission from the landowner (even if the land belongs to the state) and must notify the NHB in advance of where and when they intend to use the detector. In addition, hobbyists are required to submit search reports within one month of their fieldwork (see more in HCA 2019 ; Kadakas 2020 ; Kurisoo et al. 2020, 270). Although this article focuses on the use of metal detectors, Estonian legislation regulates the use of all types of search equipment (including magnets, sonar, etc.). Over the years, metal detecting has grown in popularity and by 2022 there were almost 900 licensed hobbyists (Kurisoo et al. 2023, 217). The number of active archaeologists is around 70–80 people, but they work across all sectors (universities, commercial archaeology, NHB, museums, etc.).

Hobbyist metal detecting of archaeological finds in Estonia has been studied only briefly, mainly with the aim of introducing new finds. Initially reports formed a chapter in an annual publication, presenting landscape surveys and newly discovered monuments (e.g. Ots and Rammo 2013 ; Rammo et al. 2014), but it developed into a separate annual article as the number of hobbyists and their discoveries increased (e.g. Rammo and Kangert 2018 ; Rammo and Smirnova 2019). More recently, this annual report of public finds has included a chapter on how the system works and on the latest developments at the NHB (e.g. Kurisoo et al. 2020 ; 2021 ; 2022 ; 2023). There is only one undergraduate thesis on the topic of the users of metal detectors and this was written before the hobby was regulated by the HCA (Kangert 2009). Additionally, one master's thesis discusses responsible metal detecting (Ulst 2012). At the same time, the lack of research does not mean a lack of opinion, and several archaeologists have expressed their views in the media, focusing particularly on the negative aspects of metal detecting on the archaeological heritage (recently Lang 2022 ; Mandel 2020 ; 2022 ; Valk 2022). Search device users are active on social media platforms and can also be very critical of heritage professionals. In both cases, archaeologists and metal detectorists express opinions without listening to the other side, which inevitably leads to stereotyping and strains relations between these two communities.

In this article we will explore how local archaeologists and metal detectorists perceive the current system of metal detecting in Estonia. Our focus is on identifying issues that are important to local heritage professionals (i.e. archaeologists working in all sectors) and hobbyists. This study will also help to understand the concerns of each target group and identify areas for improvement. This information is also valuable for evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of the Estonian approach on a broader scale.

The study carried out as part of this article is the first of its kind to examine the situation in Estonia, so the choice of questions and methods was determined by the wider objective of laying the foundations for subsequent in-depth studies involving these stakeholders. The aim was to give a voice to as many people as possible, with a minimum of predetermined response options. It was therefore decided to use an online survey with six open-ended questions, divided into three thematic groups (positive aspects, negative aspects and suggestions). The questions were designed to encourage respondents to express their thoughts about the current system. The questions were almost identical for both target groups, with the exception of question 2. As several archaeologists had expressed negative opinions about the hobby in the media (see above), they were asked directly what value they see in metal detecting for archaeology (see Table 1).

| No. | Target group | Question |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Archaeologists, hobby searchers |

In my opinion, the positive aspects of the current system of metal detector use are (what and why): |

|

2 |

Archaeologists |

The following are valuable for archaeology in the current system |

|

2 |

Hobby searchers |

It is also important to me that |

|

3 |

Archaeologists, hobby searchers |

On the positive side, I would also like to point out that |

|

4 |

Archaeologists, hobby searchers |

In my opinion, the negative aspects of the current system of metal detector use are (what and why): |

|

5 |

Archaeologists, hobby searchers |

I think the first and foremost thing to change is (what and why): |

|

6 |

Archaeologists, hobby searchers |

On the negative side, I would also like to point out that |

The survey was anonymous and no personal information was inquired and collected. The questionnaire included only very general background information (see 3.1 and 3.2 for details). Archaeologists were asked about their experience in years (given time periods) and their involvement with hobbyists (if any). Metal detectorists were asked how long they had been metal detecting (also given periods) and whether they hold a valid licence. Information about the survey was circulated on dedicated mailing lists (e.g. Estonian Association of Archaeologists; licence holders) and social media groups that connect local hobbyists. The survey was open for almost four weeks (September–October 2023) and 174 people responded. The survey was conducted in Estonian and Russian, and 52 metal detectorists (34%) chose to complete the questionnaire in Russian, but the answers were not analysed separately, as the aim of this survey is to understand the general attitudes of metal detectorists without taking into account personal information.

As this study uses an open-ended questionnaire, the results are similar to transcribed interviews and lend themselves to qualitative analysis. While there are many methods of qualitative analysis, we chose to follow the principles of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006). Thematic analysis has the advantage of focusing on the content of responses and can be also applied to archival material (Axelsen 2021, 59, and references therein). Archival material presents similar challenges to coding as open-ended questions (as discussed below), which further supports the choice of methods.

The answers were read carefully, and the main ideas reflected in them were marked as an initial set of codes, which are the basic elements of textual data used in thematic analysis. Codes were used to retrieve and categorise similar units of data from the answers (Miles et al. 2020, 63). The initial codes were reviewed after further readings and the answers were coded into a dataset. These codes were repeatedly revised, and after several cycles of coding, they were mapped thematically based on the content of the codes (Braun and Clarke 2006). The analysis follows the themes, but each code is also briefly mentioned. Although the data analysis is qualitative, the coding was done in a spreadsheet format to allow the main results to be characterised in percentages in the text (Appendix 1). Themes and codes are also presented in packed chart graphs to visualise their proportions and significance, but more extensive statistical analysis would require a different type of study and dataset.

Lastly, it is important to note that the chosen survey method, an open-ended questionnaire, made the coding process inherently challenging. Unlike interviews, the lack of direct contact with respondents made it particularly difficult to capture the subtleties of the responses (e.g. ironic remarks). Many respondents did not follow the structure of the questionnaire and wrote down all of their thoughts, critiques and praises under the first positive or negative questions. Consequently, for analytical purposes, the responses were aggregated into three broad categories that were coded separately — positive aspects, negative aspects, and suggestions — rather than adopting a question-centred approach. We hope that this has helped to reduce bias and provides a more accurate representation of respondents' intended thoughts and feelings.

On a broader scale, there are a number of papers that examine metal detecting as a phenomenon and its impact on archaeological heritage (e.g. Deckers et al. 2016; Gundersen et al. 2016) or metal detecting communities in different countries (e.g. Thomas 2012; Lykkegård-Maes and Dobat 2022). Studies comparing the attitudes of hobbyists and heritage professionals are less common (e.g. Axelsen 2021; Immonen and Kinnunen 2016; 2020; Maaranen 2016; Komoróczy 2022) and our research falls into this category. The Estonian hobby metal detecting system is characterised by its complexity, with distinctive mandatory components such as training, licensing, notification and reporting. Because of its unique approach, it attracts the attention of other countries actively considering hobby regulation. The focus of this study is on the intrinsic aspects of the system and stakeholders' perceptions of the current model, rather than delving into the social background and motivations of local hobbyists, which is a topic for a separate paper. Our survey provides insights into how the Estonian model works and what are the challenges it faces.

A total of 22 archaeologists participated in the survey, with one invalid response. This resulted in a sample of 21 participants, which represents about 25%–29% of Estonian archaeologists. We consider this response rate to be adequate for current purposes and the sample size met our expectations. It should be noted that open-ended questions require more engagement than multiple-choice questions, which may have contributed to a reduction in the number of respondents. As an aside, it is worth noting that in the Czech Republic, 40–45% of archaeologists responded to a questionnaire that was mostly multiple choice (Komoróczy 2022, 324). It also appears that Estonian archaeologists who have no contact with local metal detectorists did not respond to the survey, possibly because they felt disconnected from the subject. Also, the authors of this article and a colleague who helped us formulate the questions did not participate in the survey.

As a background question, respondents were first asked how long they had been working in archaeology (Figure 1). The majority replied that they had been working in the field for 5–15 years (n=8, 38%), with the fewest responses coming from archaeologists with less experience (n=3, 14%). The second question focused on their interaction with metal detectorists. Respondents were given the opportunity to choose from a range of answers and select all that applied. In addition, they could choose the 'other' category to provide an individual explanation (Figure 2). There was an alternative choice to indicate that they had no personal experience in this regard, but this answer was not selected. A third (n=7) of respondents had interacted with metal detectorists in a variety of ways, including working with them during fieldwork, assessing their finds (via expert opinions) and corresponding with them. It is worth noting that 76% of archaeologists (n=16) have worked together with metal detectorists during fieldwork, while the remaining respondents have only indirect interaction (e.g. assessing their finds). The small number of respondents and the considerable variability in responses to the second question made it difficult to cluster respondents based on similar backgrounds (a total of 15 different respondent profiles). Therefore, the analysis focuses separately on the respondents' work experience and their types of interactions with metal detectorists if relevant.

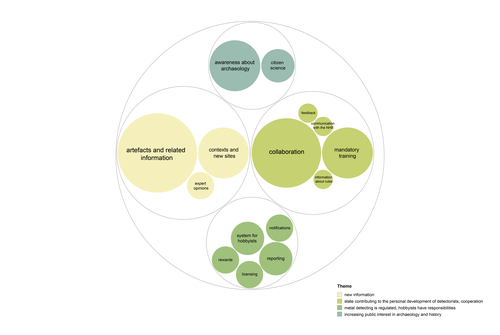

Four broad themes were identified from the codes that characterise the positive aspects of metal detecting in Estonia (Figure 3). The results showed no discernible differences in the perceptions of archaeologists based on their overall work experience or their involvement in working with detectorists during fieldwork.

Although many archaeologists are sceptical about the value of metal detecting, our survey shows that the new information gained by metal detectorists should not be underestimated (Figure 3). In particular, metal-detected artefacts and related information stands out as the most frequently mentioned aspect (n=17, 81%). As expected, local heritage professionals also emphasised the importance of contexts and the discovery of new archaeological sites (n=7, 33%). Only two archaeologists (10%) explicitly mention expert opinions as a valued aspect of the current system. Given that more than half of the respondents had been commissioned by the NHB to write them, this is an unexpectedly modest result.

Another important theme that arises from the codes is the aspect of the state contributing to the personal development of detectorists, and that there is cooperation between heritage professionals and hobbyists (Figure 3). The importance of collaboration was mentioned by over 62% of archaeologists (n=13). As one archaeologist put it: 'There are hobbyists who excel in the identification of certain artefacts, who are skilled in the use of a metal detector, and who make good partners for landscape surveys'. The importance of cooperation and personal communication was also seen as an essential aspect of explaining to detectorists how heritage professionals perceive fieldwork: 'I have met many who, thanks to this collaboration, understand the value of archaeological artefacts and realise that artefacts without context, are essentially meaningless finds'. The mandatory training programme was brought up by a third of respondents (n=7). The remaining codes, available information about rules of detecting, communication with the NHB and feedback, were noted only once.

Surprisingly, there was little emphasis on the fact that metal detecting is regulated and that hobbyists have responsibilities (Figure 3). Few respondents mentioned that they think it is positive that Estonia has a system for hobbyists metal detecting (n=3, 14%) and similarly there was little mention of reporting (n=3, 14%), licensing (n=2, 10%), notification (n=2, 10%), and reward (n=2, 10%). The responses gave the impression that archaeologists are sceptical that (most) metal detectorists adhere to the rules, but pointed out that there are some exceptions: 'For some detectorists, “playing fair” is a matter of pride'. Increasing public interest in archaeology and history (Figure 3) was the least frequently mentioned theme and includes only two codes, awareness about archaeology (n=7, 33%) and citizen science (n=3, 14%). However, the latter was not very clearly articulated and was mentioned only in passing.

There were slightly more negative (18 codes) than positive codes (15 codes) and they fell into four thematic categories, but negative answers were clearly more frequent in the survey than positive answers. The majority of codes relate to concerns that the HCA is not being fully implemented in practice and/or that some aspects of the regulation are not serving their purpose.

The theme of system deficiencies (Figure 4) represents a range of worries that archaeologists have, the most common of which is the lack of supervision over the illegal use of search devices (n=9, 43%). 'In reality, there is no control over metal detectorists — we have no idea how many people are out there without a licence, and a licence does not guarantee that a person will report their findings'. Insufficient resources of the NHB (n=8, 38%) was the second most common problem identified by heritage professionals. Another frequently mentioned serious concern relates to the slow process of placing new archaeological monuments under protection in Estonia (n=6, 29%). There are hundreds of new sites that have been discovered by hobbyists, but the state has not been able to list them as monuments (Kurisoo et al. 2022, 270). Some of the responses were very critical of this situation and it is clearly an issue that lies close to the hearts of the local archaeologists, as one respondent wrote: 'Artefacts that are collected from the same cadastral units [where there are unprotected monuments] over and over again make me despair — why aren't they protected!?' A third of archaeologists (n=6, 29%) pointed out that the speed of processing public finds is too slow, and around a fifth felt that the NHB does not communicate effectively with metal detectorists (n=4, 19%). 'Often even the most enthusiastic detectorists are frustrated by the system because their findings and information are not processed quickly enough, and the information drifts here and there'. It is understandable that these aspects undermine the confidence of metal detectorists towards the state and heritage professionals (see also Kurisoo et al. 2021, 271). Or as one archaeologist put it: 'The time lag between search activity and feedback in the form of expert opinions is too long. I could not imagine having to wait years for feedback'. There were also opinions that rewards are not justified (n=4, 19%). Less frequent were comments about the feedback (14%, n=3), the National Register of Cultural Monuments (the NRCM portal) (n=2, 10%) and one respondent noted insufficient mandatory training opportunities (n=1, 5%).

Although heritage professionals value the knowledge gained from metal detecting, they are also critical of it. The loss of heritage and scientific information was the second most common theme to emerge from the codes (Figure 4). A third of respondents believe that hobbyists collect too many finds (n=6, 29%), which in turn damages the potential find context. Archaeologists also feel that the slow dissemination of information about metal-detected artefacts by the NHB is a problem (n=5, 24%). A few respondents pointed out a somewhat uneven quality of expert opinions (n=3, 14%) and two worried that the information provided by hobbyists about location of sites can be inaccurate (10%).

A third theme that surfaced from the responses is related to the violation of the laws (Figure 4). More than a fifth of heritage professionals feel that offenders are not punished (n=5, 24%) and this poses a threat to archaeological heritage. It was also emphasised that the local police show little interest in protecting cultural heritage. At the same time, only a few archaeologists explicitly mentioned illegal metal detecting as a concern (n=3, 14%) and two touched upon underreporting as a problem (n=2, 10%). However, the low number of responses does not mean that the local community of heritage professionals fails to see these aspects as a problem. On the contrary, the problem of illegal use of metal detectors is well known (e.g. Ulst 2010; Mägi et al. 2015; Valk and Kaseorg 2021) and also discussed in the media (see above), but it seems that the respondents were mostly focused on how the current system works and not on the wider issues related to metal detecting in Estonia. The last negative issue mentioned by Estonian archaeologists is the low public awareness of archaeology among hobbyists and landowners (Figure 4). This topic includes two codes, with general awareness about archaeology (n=5, 24%) being more important than documentation skills (n=1, 5%).

There are some differences in the responses between heritage professionals with shorter and longer professional experience. The archaeologists with longer experience voice their worries about the loss of cultural heritage and scientific information more strongly than those with less experience. However, the latter are more critical of the NHB, stressing the importance of supervision, slow processing of finds and inadequate communication with hobbyists.

The majority of archaeologists (19 respondents) highlighted specific challenges and potential changes to the current system that are necessary in their view. The most frequently mentioned problem is the prioritisation of heritage by the state, and it mostly overlaps with the issues defined in the previous section. The most common suggestions are to speed up the processing of public finds (38%, n=8), strengthen supervision (33%, n=7), increase penalties for illegal hobby searches (24%, n=6), and increase the number of archaeologists working at the NHB (24%, n=6). These responses reflect the concerns of heritage professionals and are not easily resolved. More actionable recommendations are listed under the theme of education and cooperation, and include general suggestions for raising archaeological awareness (19%, n=4), increasing training opportunities (10%, n=2), and collaborative projects, such as joint fieldwork (14%, n=3). The remaining codes were more difficult to group because they represent unique ideas and several of them were expressed by the more experienced heritage professionals. Examples include registering all detectors or limiting rewards to smaller sums, while younger archaeologists stressed the need for increased monitoring and punishment of illegal metal detecting.

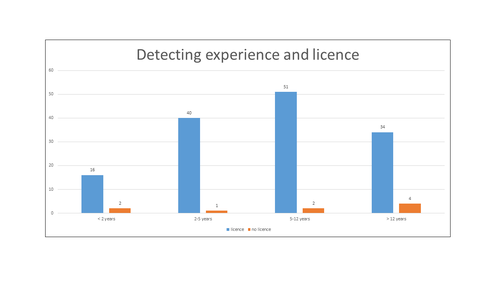

A total of 152 hobby searchers responded to the survey; two responses were invalid. Most of the respondents (n=141, 94%) held a licence (Figure 5). At the time of the survey, there were around 950 licence holders, of whom approximately 15% responded. It is worth noting, however, that licences are valid for five years, during which time some hobbyists may become inactive. Based on the 2022 and 2023 data, it appears that only one-third of the licence holders submitted at least one search report. From this perspective, the response rate of around 45% is quite significant. Countries without a licensing system have more difficulties in estimating the number of (active) hobbyists. To take the example of the Czech Republic mentioned above, their survey covered an estimated 5-10% of the metal detecting community (Komoróczy 2022, 324). However, in a study conducted in Finland, about 25% of active hobby metal detectorists responded (Immonen and Kinnunen 2016, 168). Responses from unlicensed (N=9, 6%) detectorists are valuable as they provide an opportunity to hear the opinions of a group that usually has no contact with the local heritage professionals. The number of unauthorised metal detector users is not known, but is estimated to be over a hundred people (Kadakas 2021). However, there is no information about their activities and level of involvement in this hobby.

The majority of the respondents (n=53, 35%) have been metal detecting for 5 to 12 years, which means that they are familiar with the 2011 and 2019 legislation changes (Figure 5). The second largest group of 41 people (27%) have been hobby searchers for 2-5 years and they have mostly practised their hobby according to the HCA 2019. They are followed by the group who have been detecting for more than 12 years (n=38, 25%) and who started before metal detecting was regulated in Estonia. The largest number of unlicensed hobbyists fell into this group (n=4). The smallest group of respondents (n=18, 12%) are newcomers to the hobby, who have been metal detecting for less than 2 years.

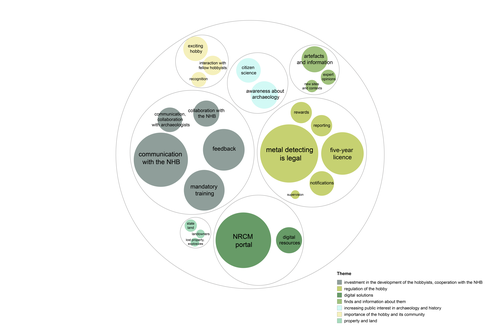

As notably more detectorists than archaeologists participated in the survey, their responses were also more varied and covered more aspects of the hobby. The majority of hobby searchers (n=129, 86%) identified at least one positive aspect of the current system. Their responses were categorised into 23 codes and grouped into eight broad themes.

The most important theme for the detectorists was investment in the development of the hobbyists and cooperation with the NHB (Figure 6). The most frequently mentioned code was communication with the NHB, which 26% of hobbyists found positive (n=39). It seems that most respondents meant direct communication in the form of emails, telephone calls or face-to-face meetings. Some 15% of hobbyists (n=23) also noted the importance of getting feedback on their discoveries. The mandatory training programme had a similar value for participants (n=22, 15%). Other codes were mentioned by less than 10% of the detectorists and include topics such as collaboration with the NHB (n=9, 6%) and communication and collaboration with archaeologists (not affiliated with the NHB) (n=7, 5%). For a few respondents these issues were really important; for example one detectorist wrote: 'Most importantly, [I value] the opportunity to work closely with professional archaeologists. The ability to express my opinions/theories to them and their genuine interest and attention. Overall, a very positive impression of communication!'.

The second most common theme is the regulation of the hobby (Figure 6). This includes the fact that metal detecting is legal in Estonia, which was highlighted by a third of respondents (n=45). As one hobbyist put it: 'Archaeology has always been a particularly fascinating discipline for me, but if it weren't for this hobby, pursuing it would mean going back to university as a middle-aged person...'. The five-year licence was worth mentioning for 16% (n=24) of detectorists. Other codes in this theme were noted less often as positive aspects of the current system: notifications (n=8, 5%), reports and, surprisingly, rewards were mentioned only six times each (4%). Supervision of the illegal detector use was important to one person.

Digital solutions also received a more favourable mention than the other topics (Figure 6). The NRCM portal (n=41, 27%) and other resources, mainly thematic map applications of the Estonian Land Board (n=9, 6%), were stressed by respondents. The NRCM portal is an information system that combines information on all protected monuments and other culturally significant sites and objects. It has a user interface that allows different stakeholders (landowners, detectorists, heritage professionals, etc.) to interact with the NHB by submitting applications, notifications, reports and other types of documentation. It is important to note that although 27% of the hobbyists surveyed found the portal to be generally positive, in the negative sections of the questionnaire the same people also pointed out its flaws and malfunctions and the overall problematic UX/UI design.

Unexpectedly, there was little mention of finds and information about them (Figure 6). Only 14 detectorists (9%) emphasised the importance of metal-detected artefacts and related information. Moreover, the expert opinions (n=3, 2%) and information about new sites and contexts (n=2, 1%) were rarely mentioned, although these might overlap with the code feedback. The theme of increasing public interest in archaeology and history was modestly reflected in the responses. Increased archaeological awareness was brought up 10 times (7%) and citizen science was implicitly mentioned by 5% (n=8) of the hobbyists. The importance of the hobby and its community was also a modest theme in the responses (Figure 6). Only 8 respondents stressed the exciting nature of metal detecting (5%), as poetically expressed by one person: 'Every new piece of arable land is like a new planet'. Interaction with fellow hobbyists was brought up by 5 people (3%). This may sound surprisingly low, but in Estonia metal detecting tends to be an individual hobby and joint activities are rare. The recognition by the state (i.e. society) was barely mentioned (n=3, 2%). In the theme of property and land (Figure 6), the simplicity of getting a landowner's permission from the State Forest Management Center was mentioned twice and interactions with private landowners once. One survey participant also found that uncovering lost property and explosives is a beneficial side of metal detecting.

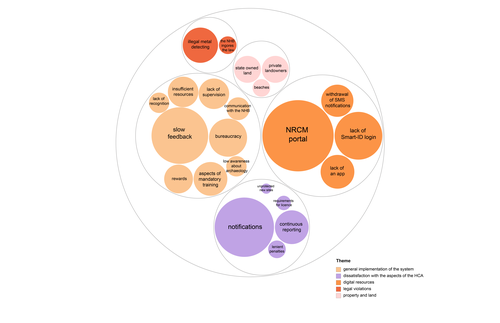

Of 150 hobby searchers, 132 (88%) identified at least one negative aspect of the current system. Their responses were categorised into 23 codes covering five themes. Estonian hobbyists are mainly dissatisfied with the general implementation of the system (Figure 7). Slow feedback was the most frequently cited problem (n=31, 21%). This includes delays in the NHB responses to detectorists' reports and the slow evaluation of finds – these are well-known problems (Kurisoo et al. 2021, 271), and were also noted by some of the archaeologists surveyed. Approximately 9% of hobbyists (n=14) expressed dissatisfaction with the general bureaucracy of the current system, without specifying which aspects they were concerned about. Presumably, obtaining permission from landowners, notifying the NHB before searching and reporting would all fall into this category. Some respondents (n=11, 7%) felt that the mandatory training courses were too expensive or were organised sporadically and only in large cities (mostly Tallinn). This problem seems to be important for unlicensed respondents, as 7 out of 9 mentioned it. Several detectorists brought up poor supervision of illegal detector use and insufficient resources of the NHB as a problem (both codes 6%, n=9). Some of the ideas expressed regarding this matter could just as well have originated from the heritage professionals who share this concern. For instance: 'There are many searchers without a licence and lenient or non-existent penalties for the misuse of finds/sites of cultural value' or: 'The state could do more to fund archaeology – to value it. There do not seem to be enough archaeologists'.

A reward sum that was either too small or ambiguously determined was problematic for 8 (5%) questioned hobbyists. There were some misunderstandings about how the rewards are determined, and one person even suggested that the NHB was involved in some sort of conspiracy. It is also important to note that in Estonia rewards can be monetary, but do not have to be and this was also noted as a disappointment: 'A hobbyist expects a financial reward, but in many cases receives a book'. While a quarter of the detectorists saw communication with the NHB positively, for 3% (n=5) of hobbyists, it constituted a negative aspect of the system. It is likely that their dissatisfaction stemmed from the slow response time rather than the nature of personal communication. Some respondents pointed out that the awareness about archaeology of their fellow hobbyists is insufficient (n=4, 3%) and an equal number of hobbyists felt that the detectorists do not receive enough recognition from the state and the archaeological community.

Opinions expressed under the previous theme can provide valuable information for the NHB to improve its relationship with the detecting community. However, the criticism grouped under the theme of dissatisfaction with the aspects of the HCA (Figure 7) is more complicated as it is related to effective legislation. The requirement to notify the NHB prior to a search activity was considered a negative aspect of the system by 23% of hobbyists surveyed (n=34). At the same time, it is important to note that this statistic does not reflect just opposition to the idea of notifications in general, but also the technical problems associated with the process, as it depends heavily on the proper functioning of the NRCM portal, with which many users have had poor experiences (see below). The obligation to report after each search was mentioned by 11 hobbyists (7%), the majority of whom (9 people) have been detecting for more than 5 years, i.e. they obtained their licence under the previous system where the detectorists had to submit annual reports only. Too lenient penalties for breaking the rules were pointed out three times (2%). In addition, two people felt that requirements for obtaining a licence are unfair: one disagreed with the age limit (the licence holder must be at least 18 years old) and another felt the state fee for the licence (50 euros) is too high. Only one person expressed concern that the archaeological sites discovered by the detectorists are not taken under protection, a common concern among local archaeologists (see above; Kurisoo et al. 2022, 270).

In terms of digital resources (Figure 7), the NRCM portal was the most frequently mentioned, with a third of hobbyists finding it problematic (n=49, 33%). Even a person without a licence mentioned that the NRCM portal does not work properly. The system is known to have malfunctions as it is constantly being developed and improved. It does not work when internet connectivity is patchy and so far the only authentication methods for logging in have been an ID-card or Mobile ID. Users are annoyed because the ID-card can only be used on personal computers, and while Mobile-ID can also be used on smartphones, it requires monthly payments. The third very common app-based digital identification service in Estonia, Smart-ID, was not yet integrated into the NRCM portal at the time of data collection for this article. Its absence was mentioned as a negative aspect of the current system by 15% (n=22) of hobbyists surveyed. During the preparation of this article the NRCM portal was updated to include Smart-ID as an authentication method. As another practical note, the lack of an app for detectorists was cited as a problem by 7% of participants (n=11). Ten individuals (7%) expressed concern about the absence of the option to send search notifications via text messages. The opportunity to notify searches via SMS was widely adopted by hobbyists since the introduction of notification requirements in the 2019 HCA. SMS notifications were discontinued by the NHB in October 2022, as the manual entry of notifications into the NRCM portal by the NHB staff placed an additional burden on already stretched resources. The technical aspects of the system, such as the submission of notifications and reports, should be made more user-friendly, as problems with the NRCM portal and the discontinuity of SMS notifications are issues that seem to create a negative perception of the whole system among hobbyists. Phrases such as: 'terrible to use', 'difficult', 'time-consuming' were used to illustrate the user-experience with the NRCM portal.

In the context of legal violations (Figure 7) 12 hobbyists (8%) highlighted concerns regarding illegal metal detecting, while three hobbyists (2%) expressed a feeling that the NHB is not adhering to the rules and legislation. Specifically, one person raised concerns about the way finds are processed and assessed, another noted a difference in the treatment of 'magnet fishing' compared to metal detecting and the third did not specify the nature of their concerns. On the issue of property and land (Figure 7), 7 people (5%) were unhappy that searches on state-owned land require landowner's permission, same as on private land. The same number of hobbyists (n=7, 5%) mentioned problems with getting a permit from private landowners or land tenants. Four respondents (3%) felt that the rules for detecting on the beaches should be more lenient than in other places, as there is less chance of discovering something of archaeological significance.

Suggestions for improving the current system came from 77% (n=115) of the hobbyists who took part in the study. As expected, most recommendations focused on addressing issues that were considered highly problematic. The most common suggestion (n=23, 15%) was to simplify the submission of the search notifications or abandon the requirement altogether. In particular, 9% of (n=14) respondents felt that the option of sending notifications by SMS should be reinstated. Improving the NRCM portal and developing a specific application for hobbyists were both suggested by 18 individuals (12%). These proposals underline the importance of promoting a positive user experience for hobbyists in carrying out the tasks mandated in the HCA. Improving the speed of feedback was proposed by 11% of hobbyists (n=16), even though the number of people who identified it as a problem was almost twice as high. Suggestions to make reporting easier or less frequent came from 12 hobby searchers (8%), with the majority (n=9) holding a licence for longer than 5 years. Other recommendations were less frequently mentioned, including the need for more affordable training courses (n=10, 7%), raising awareness among the detectorists (n=10, 7%), fostering inclusion of the detectorist community by archaeologists and the NHB (n=8, 5%), and enhancing monitoring of illegal activities (n=9, 6%), among others.

Although our study focuses primarily on the perspectives of archaeologists and hobbyists within the Estonian legal and practical context of metal detecting, the results also facilitate a broader discussion of aspects related to hobby searching, considering the experiences of other countries (e.g. Finland, Czech Republic, Norway) that have undertaken similar research.

The small size of the Estonian state and nation puts pressure on the role of local history, language and culture to be meaningful and relevant in the present and the future. It may also explain why Estonia has adopted the approach that all finds of cultural value are by default the property of the state, and why every stray or metal-detected find is treated as a potential in situ artefact. This seems to have also influenced why Estonia has chosen to legalise the use of search devices by hobbyists in a controlled way, with mandatory training and licensing along with notifying and reporting obligations (see above). It was felt that banning the use of metal detectors would drive the hobby underground and that the loss of information would be too great. Also, there are no good examples from countries with restrictive legislation of effective monitoring of illegal detector use (Dobat et al. 2020, 273).

Besides the small size of the country, it is also important to note that the Soviet occupation and life behind the Iron Curtain also left their mark, despite Estonia's successful rebuilding as a state since 1991. The emergence of civil society, including citizen science, has taken place in a very short period of time and is rooted in different ways in different areas. Moreover, decades of top-down approaches have had a direct impact on how different stakeholders engage with cultural heritage. Although there have been noticeable changes in the way heritage is perceived and treated by professionals over the last decade (Konsa 2019), there is still a long way to go before the democratisation of heritage and archaeology is achieved.

In the professional archaeological community in Estonia, everyone knows each other, and archaeologists are used to their role as experts. Archaeologists understand the need to raise awareness of archaeology in society and to share their knowledge (Kadakas 2021), but when metal detectorists and their discoveries are discussed in the media, the tone is usually negative. That is similar to other countries — the growing popularity of hobby metal detecting is often met with caution and criticism by the professionals in the media (Axelsen 2021, 128 and references therein). Our study clearly shows that Estonian archaeologists are currently collectively concerned about enforcing the HCA and protecting newly discovered sites, which explains their worry about the wide use of metal detectors. Moreover, many archaeologists in Estonia and elsewhere feel a strong sense of personal responsibility when conducting excavations (e.g. Frank et al. 2015) and metal detecting has the image of being a leisure activity with a lower level sense of responsibility.

At the same time, metal detecting is here to stay, whether heritage professionals like it or not. Paradoxically, local archaeologists who are genuinely concerned about heritage would like to see metal detecting as something that falls solely on the shoulders of the NHB. Yet the NHB lacks the capacity to deal with new information about sites and finds in a timely manner, which contributes to various problems. It seems that the popularity of the hobby was not anticipated when the use of search devices was regulated. As a result, the number of hobbyists has increased significantly, while the number of the NHB staff has not (see Figure 8). In addition, the volume of finds reported in 2022 was alarmingly low (see more in Kurisoo et al. 2023, 224), highlighting the need for major changes to the system. Such solutions require political will, are time-consuming and imply that only the state (or the NHB archaeologists) can be responsible for the local cultural heritage. In contrast, the views of archaeologists in the Czech Republic should be mentioned, who see it as inevitable to be active members of the hobby metal detecting community (Komoróczy 2022, 329). The need to be more active partners is also recognised by Finnish archaeologists (Immonen and Kinnunun 2016, 167, 177).

Developing deeper cooperation between heritage professionals and local hobbyists is one of the most common recommendations in the academic literature (e.g. Immonen and Kinnunen 2016, 177; Maaranen 2016; Rasmussen 2014, 88; Wessmann et al. 2023). Estonian archaeologists have collaborated with local metal detectorists on fieldwork, written expert opinions for the NHB, and participated in training as lecturers, not to mention private correspondence, but so far cooperation and communication are sporadic and often limited to a few hobbyists. It seems that Estonian heritage professionals may need some convincing that metal detecting can be approached as citizen science with clear benefits for archaeology (cf. Wessmann et al. 2023). Archaeologists tend to see themselves as experienced experts with superior knowledge in their field, and may disregard the expertise of hobbyists too lightly or have difficulty trusting the motives and information provided by the metal detectorists (see also Axelsen 2021, 116-17, 122-26). As already mentioned, Estonian heritage professionals were not prepared for such a rapidly growing detectorist community, and there are still many concerns about underreporting and illegal use of search equipment. Similar concerns have been noted in other settings when the hobby began to gain popularity and wider attention (e.g. Immonen and Kinnunen 2016, 176; Komoróczy 2022 328). Moreover, bad cases tend to overshadow the good and lead to generalisations about the metal detecting community as a whole, or to the division of local detectorists into 'good'/'responsible' or 'bad'/'irresponsible' (Kadakas 2021), which is too simplistic and does not represent the complexity of the hobby and diverse motivations and aims of detectorists (Rasmussen 2014).

As other studies have shown, detectorists tend to form quite heterogeneous communities (e.g. Axelsen 2021; Immonen and Kinnunen 2016). It is difficult to assess how much can be said about a common identity among Estonian hobbyists until more precise studies are carried out. There are a few clubs, but metal detecting is mostly an individual hobby. It seems that the online environments serve as a place to share (sometimes anonymously) questions and opinions about the hobby and discuss recent discoveries (see also Maaranen 2016). Perhaps a representative organisation uniting local hobbyists would benefit local detectorists as a community and give them a greater sense of belonging. The current survey suggests that both the concerns and the benefits of the system are largely shared by Estonian 'individual hobbyists'. For heritage professionals in Estonia, it is certainly eye-opening that local detectorists are primarily interested in feedback on their finds rather than rewards, as many archaeologists have previously assumed.

Given the historical and cultural background of Estonia, it is unlikely that the system for using metal detectors will ever be as liberal as in countries such as Denmark (e.g. Dobat 2013) or England (e.g. Lewis 2016). The Estonian approach to metal detecting is characterised by an emphasis on the importance of the potential find context, which has led to a controlled and regulated organisation of metal detecting. The impact of ploughing and land management on the archaeological heritage and finds within the plough layer has not been a central aspect in assessing the (positive) impact of the hobby (cf. Haldenby and Richards 2010) in Estonia, which has also shaped local heritage professionals' perceptions of the impact of this hobby. Regarding the Estonian example, it is worth noting that private metal detecting traditions do not go back very far, with regulations being introduced in 2011. Our research highlights several aspects of the implementation of the current organisation of this hobby that need improvement, as expressed by detectorists and archaeologists. Despite its shortcomings, our study provided a clear signal that the differences between the views of the two stakeholder groups are not as dramatic as previously thought. Many Estonian archaeologists have cooperated with detectorists and both stakeholders share similar views on a variety of aspects (e.g. new information, training). The underlying differences between the archaeologists and detectorists appear to be related to issues of trust, professional status and sense of responsibility towards the heritage. Similar issues are being discussed in other countries and it seems that closer cooperation offers an opportunity to learn from each other and ultimately allows archaeological heritage to be seen as a shared responsibility that both stakeholders value and engage with.

We thank all survey respondents for taking the time to share their views and suggestions. We are grateful for the assistance of Nele Kangert in our discussions, and to the National Heritage Board of Estonia for circulating the survey among local hobbyists. This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 101003387.

Appendix 1: The dataset with thematic mapping and codes is available at https://doi.org/10.23673/re-479

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.