Cite this as: Nedergaard Dreiøe, K., Hertz, A., Abramsson, G. and Søgaard, R. 2025 Perspectives on and from the Danish metal-detecting community, Internet Archaeology 68. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.68.7

In Denmark, the practice of metal detecting has witnessed significant growth, attracting enthusiasts of diverse backgrounds since the early 1990s. However, the lack of a formal, unified approach to educating both prospective and current metal detectorists presents a considerable challenge. Compounding this issue is the absence of accepted standardised codes of conduct, a situation prevailing among individuals, metal detecting clubs, and museums. In consequence, there is a rise in the reporting of detecting on protected sites, the improper handling of artefacts, and even artefacts not being reported.

We believe there is a need to restructure these processes and budgets so that The National Museum of Denmark (hereafter NatMus) is not the sole institution receiving funding through the Danish Financial Act to handle the rapidly increasing number of metal detector finds flowing through local museums to the National Museum every year. This surge places significant financial strain on local museums. Therefore, we advocate for the financial prioritisation of the role that local museums play in the registration and processing of archaeological finds. This would ensure a high level of scientific rigour associated with these discoveries, a swifter processing time, and greater efficiency in the future.

While NatMus has the authority to reduce rewards if, in their opinion, proper care is lacking, it can only recommend what constitutes proper care (omhu). The term omhu, as defined by NatMus, distinguishes between chance finds, such as those made by dog walkers, and deliberate artefact searches. The latter aligns largely with archaeological principles, albeit adapted to the context of detecting only in the plough layer. However, both the terms omhu and the precise definition of Danefæ (defined below) are not extensively detailed within the Danish Museum Act. These aspects remain at the discretion of NatMus and can be found on their webpage. Consequently, local museums have varying interpretations of what makes acceptable care by detectorists, ranging between minimal requirements to extensive documentation.

The Viking Age holds a significant place in Denmark's historical consciousness, not only because it marks the gradual emergence of the Danish kingdom, but also due to the period's lasting legal and political structures. Historical sources from the time describe assemblies (ting), legal practices, and systems of governance as relatively decentralised compared to later medieval institutions. These features are often emphasised in modern interpretations of early Danish history and have occasionally been linked - retrospectively - with ideals such as community-based decision-making and limited hierarchies. While such connections should be treated with caution, they illustrate how the Viking Age continues to inform contemporary understandings of Denmark’s institutional roots. Building on this historical background, it is also relevant to consider the origins of Danish treasure trove legislation, which, though medieval rather than Viking, reflect continuing developments in governance and law. In 1241, King Valdemar II issued the Code of Jutland, which states:

"... what no one owns, the king owns. If any man finds gold or silver in mounds or by plough or in any other way, then the king shall have it".

This is widely regarded as being the oldest predecessor of a treasure trove legislation in the world, However, it is crucial to note that this was not driven by a desire to preserve antiquities for cultural heritage. Instead, it aimed to bolster the treasury and maintain a position of power - a strategic pursuit continued under Valdemar II to expand the Danish realm, following in the footsteps of his predecessors, Valdemar the Great and Knud VI.

The King had faith in people delivering those precious objects that emerged from the Danish ground. But more importantly, it established a precedent for the still-dominating principle that finders are indeed not keepers but are however obliged to hand over valuable findings to the King. In the 17th century, this principle was strengthened by adding a compensation mechanism to encourage people to deliver what was then in Old Norse labelled dánarfé (“inheritance without a living heir”), a compound of *dán (“death”) + fé (“property”) (Petersen and Høstmark 2008).

Today, a clear legal framework mandates that items believed to be Danefæ or treasure must be reported to NatMus, which in practice takes place through 27 local culture historical museums with archaeological responsibility (Museumsloven). When declared as Danefæ, the finder is rewarded a tax-free compensation; however, this compensation may not necessarily align with an identical item's potential value on the international antiquities market (where resale is legal). The principle enjoys wide acceptance in Denmark but faces challenges, especially from novice detectorists, due to perceived delays in processing at local museums. NatMus, in contrast, has been subject to specific time limits for processing Danefæ, but the local museums currently lack such defined timeframes. Coupled with only a small percentage of the ten thousand objects found each year actually being exhibited or utilised in publicly available research, this has led some detectorists to believe that artefacts are better cherished and admired at home rather than tucked away in a pile of work for years at the local museum, and later hidden in the depths of a dark museum storage facility at the National Museum.

The emergence of commercially available metal detectors in the 1980s called for regulation to protect the national archaeological heritage. Many Danish archaeologists feared that the advent of the metal detector would create so-called 'British conditions' with grave robbing and nighthawking of archaeological sites if not banned (Nielsen and Petersen 1993). The metal detector was depicted as the Devil's creation in the journal Skalk, 1983/1. It was hanging in a balance: embrace or ban. In the end, the 'old way' won.

The result was a road paved with trust and dialogue for those who pursued exploration with metal detectors. They were given freedom with responsibility (Henriksen 2016, 19). Freedom to go where the landowners grant access (excluding restricted archaeological sites/areas), and responsibility to evaluate and hand in finds they believe are of archaeological value.

Today the King's privilege has been transferred to NatMus acting on behalf of the Parliament. Amongst other initiatives, NatMus seeks to support the 'Danish Model' through providing:

For the local museums, the Danish Model is supported by:

The Ministry of Culture also indirectly supports the 'Danish Model' through providing an online national heritage map Fund og Fortidsminder which is open access and where all archaeological finds and sites, including those made by metal detectorists, are registered (in varying detail) and can be accessed by both a map-search and a traditional text-search by place name, parish and municipality, for example.

Information sharing between the museums, both local and national, and the public is a critical component of the Danish approach, and this is highly appreciated by Danish metal detectorists.

The umbrella organisation Danske Amatørarkæologer (DAA) unites 18 detecting clubs, but it has not historically engaged in any political advocacy. Though there may be a shift on the way, it is unlikely to happen in the near future. The lack of regular communication between local clubs and DAA has led to some clubs disassociating from DAA. Attempts to create other forums have also failed. This has left the role of educating all newcomers to metal detecting to club introductions and some engaged individuals on Facebook.

The decision to apply a trust-based regulation of Danish metal detecting has opened the playing field for the amateur archaeologists to populate the space with their own structures and behaviour-regulating mechanisms.

The first generation of metal detectorists that took to the fields were probably a relatively homogeneous group of technical-minded nerds with an interest in history and a knowledge of the minesweepers used in World War II. They started to create detectorist clubs around the country. Twelve of these clubs have developed more formal organisations, some of them with several hundred members. These clubs developed a strong sense of responsibility towards the privilege assigned to them, and developed their own individual codes of conduct, club houses, websites and formative structures for newcomers. Further, the acquisition of knowledge to identify their findings and to make a qualified pre-screening in the field spurred the development of very skilled amateur archaeologists amongst the detectorists. They became specialists in various categories of finds that even professional archaeologists would consult. Databases of competencies, compilations and knowledge resources have all been developed by these amateur archaeologists, accessible for everybody and accelerating the competence building of newcomers and experienced metal detectorists alike.

The number of active metal detectorists grew slowly but steadily during the '80s through to '00s. Regional detector clubs were established either as independent societies or as organised groups within established amateur archaeological societies. The emergence of Facebook created an online meeting place for Danish detectorists, notably the Facebook group 'Detektor Danmark', created in 2012, where people could brag about finds, seek knowledge and ask for help about technical problems. The Facebook group to this day has also functioned as a monitoring tool for the identification of unwanted behaviours while also facilitating public education and familiarisation with the environment, relevant legislation, best practices, and the heightened ethical standards within the metal detecting community.

As Denmark is a fairly small country, a national self-governing group is in many ways an efficient regulatory mechanism. Occurrences of mishandling or improper treatment of artefacts have been observed and addressed internally to prevent escalation and provide education, thus mitigating the need for the local museums to involve authorities. Identification of individuals engaging in unauthorised activities, such as 'nighthawking' or trespassing on protected prehistoric monuments, have also been promptly identified, leading to immediate notification of the relevant authorities.

Achieving common ground remains a complex challenge, and this is especially sad as collaborative efforts between archaeologists and engaged detectorists with a high level of omhu/proper care have produced amazing results. The following are examples selected from some of the activities involving some of the authors.

Sønderjyllands Amatørarkæologer - Arne Hertz

As the chairman of a local archaeological society, Sønderjyllands Amatørarkæologer, that has gradually transitioned into a detecting club, one of my primary responsibilities is to serve as a facilitator for promoting a sense of proper care - omhu in the Danish Museum Act. To fulfil this role, we maintain an informative website, a Facebook page, and conduct two one-day detecting introduction sessions annually. These sessions consist of a PowerPoint presentation in the morning and an afternoon in the field guided by experienced detectorists. We also distribute find slips for registering artefacts and ensure follow-ups during rallies and club meetings. This approach is effective for individuals who discover Sønderjyllands Amatørarkæologer's resources or join other like-minded clubs. However, a growing influx of newcomers, enticed by media stories of valuable discoveries, and supermarkets selling detectors or free detectors bundled with magazine subscriptions, has led to a surge in hobbyists in all age groups, ranging from preschoolers to retirees. Unfortunately, the education and access to relevant information for this diverse group remain inconsistent.

Compounding this problem is the lack of a unified, comprehensive nationwide guide. Individuals are currently often directed to local museums, private websites or social media pages for information, such as Allan Faurskov's website or the private page 'Detektor Danmark' on Facebook. Consequently, my ambition over the years has been to foster the creation of written materials that all clubs and museums can collectively endorse and employ in the education of newcomers to the hobby. While this remains a crucial need, it has become apparent that an online course, enabling participants to progress at their own pace, could be a more inclusive approach. The objective is to reach a wider audience at an earlier stage, with assessments in the form of control questions and a final exam, resulting in an auto-generated PDF diploma for successful candidates. To facilitate this, a demo using EasyLms.com, a Learning Management System (LMS), has been developed with assistance from Martin Hirtius from our club. I facilitated this by using links to websites, pictures, videos and text. Ideally, the national finds registration scheme, DIME, should host this LMS. However, the lack of cooperation among museums and detecting clubs does hamper progress in establishing common ground for defining and ensuring adequate standards of omhu to be used in such an LMS.

The vision of a detector school through an online LMS remains in a state of uncertainty and awaits broader collaboration, especially because all LMS platforms require a monthly fee that is beyond the economic capacity of an individual or club. But it is my hope that this article may be a small step towards achieving this more unified approach to educating and upgrading detectorists.

The Danish Archaeological Association Harja - Glenn Abramsson

The Danish Archaeological Association Harja was founded in 1971. The association gathers archaeology enthusiasts from the island of Funen and the smaller islands south of Funen. One of the active groups within the association includes members interested in metal detecting. This part of the association has steadily grown over the years due to the increasing interest in metal detecting as a hobby in Denmark.

As a consequence of the rise in active metal detector users, Harja, in collaboration with local museums on Funen and the islands, saw the need for increased efforts in educating these new metal detector users before they actively started searching. This was done with the aim of informing them about the requirements imposed on metal detector users by museums and legislation but equally to help them get started with the metal detecting hobby.

It was decided to develop course materials that would form the basis for a course held at Harja's clubhouse. The course content would be presented by a representative from one of the local museums as well as by active and experienced metal detector users in Harja. The museum's representative would instruct on the legal requirements and guidelines that the museum expects metal detector users to follow. More practical aspects related to metal detecting would be taught by Harja's own active metal detector users.

This course has been conducted continuously since 2019. The total duration of the course is about 5 hours plus breaks. The course, the content of which is outlined in Appendix 1, has been held as two evening courses or as a single-day weekend course.

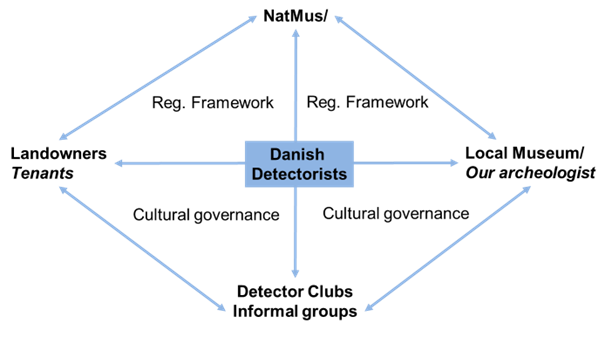

There is little doubt that the trust-based approach has been very successful in terms of avoiding the problematic situations that have occurred elsewhere, with a relatively low degree of illegal unearthing of artefacts and destruction of archaeological contexts. When we were asked to draw out some perspectives on the Danish metal detecting community for this special issue, a mental map of the main actors and the relationships between them became useful in order to structure the various arguments in a coherent way (Figure 1). The model does not by any means pretend to be all-inclusive or refer to any particular theoretical approach, rather it is just a product of a metal detectorist's (Dreiøe) strand of thought.

The model points to actors as individuals and as organised entities, and to the formal and informal governance or regulating frameworks that guide and determine how these actors act and interact, and as a result it creates a particular community, albeit a community that is dynamic and constantly undergoing change. Thus, when looking at the Danish metal detecting community, it is an evolving organism with some particular characteristics, some of which we present here.

Today, the majority of metal artefacts exhibited in Danish museums have been found by detectorists or originate from archaeological excavations which have been initiated because of detector finds. In contemporary discussions within the museum and archaeological communities, there is a noticeable shift happening in how they view interactions with detectorists and handle their finds. While some see this engagement as enriching, especially in terms of public involvement, others find it burdensome, particularly for local museums that struggle with limited resources. It's worth noting that this burden is primarily financial since museums often lack funding to deal with the influx of metal detector finds.

In response to this challenge, many museums have started hiring specialist staff to manage the increasing number of discoveries and foster better relationships with metal detector users. This proactive approach has led to improvements in how we register finds, communicate with stakeholders, and integrate these artefacts into our research and exhibitions. However, without clear and consistent guidelines, there is still significant variation in how different museums handle finds. The prevalence of finds from metal detecting varies widely from one archaeological area to another, further complicating matters. The quantity and quality of these finds calls for a substantial reorientation of the scientific practices and foci of all museums with responsibilities towards the metal detectorist community.

In recent years, museums have increasingly recognised the research potential of metal-detected finds and have begun to integrate them into their research strategies. Today, several archaeologists and museum professionals have their academic career closely tied to local detectorist communities and their achievements. Archaeologists are to a still larger extent integrating metal detecting as a natural part of the scientific investigation during excavations. Some museums now hire detectorists or use volunteer detectorists while archaeologists themselves take up metal detecing, blurring the traditional roles.

Quite a few detectorists have also found themselves taking on a liaison role between landowners and museums, as the museum professionals cannot possibly be in contact with all landowners in their area of archaeological responsibility. When a find calls for archaeological excavation, it is of critical importance that the landowners are positive towards the intervention from the local museum. This includes informing landowners about potential outcomes (such as excavation if significant objects are discovered) when seeking permission to search on their land. This is particularly important in terms of financial implications, as landowners do not bear the cost of excavation prompted by metal detector findings. In most cases, the excavation can be planned according to the active crop season, or the landowner will be provided with alternative arrangements, such as the reimbursement of destroyed crops during the active crop season. Landowners may deny museums any excavations that are not related to their own construction activities. It is evident that there is a process of integration and stronger ties building between the stakeholders and organisations in the Danish metal detecting community, where mutual knowledge and competence creation and sharing is being accelerated. In many ways, it is fair to say that the Danish model of regulating metal detecting has been instrumental in developing one of the most significant examples of citizen science in Denmark. This process however, together with other external factors, is putting the Danish model under pressure.

'Freedom with responsibility' (mentioned earlier) as a governance framework depends on the prevalence of shared cultural and ethical values between the Danish detectorists. However, developments over recent years have challenged the coherence of this system.

Spectacular finds and technological advances that make the hobby more accessible have resulted in a rapid increase in public attention, and subsequently in the number of detectorists (also from abroad) on the Danish fields. In 2012, approximately 3,000 detector finds were received by NatMus for Treasure Trove assessment. Six years later this number had grown to around 18,000.

With this growing community, the established detectorist societies have voiced concerns over the more diversified nature of detectorists' motivations and agendas for engaging with the hobby (e.g. Lykkegård-Maes and Dobat 2022) such as treasure hunting for personal gain rather than for the common good, less respect for the formal and informal codes of conduct.

Increasing tensions can also be observed in the Facebook Group 'Detektor Danmark, where the nature of dialogue has become more aggressive, where we see more trolling and less concern for exchanging viewpoints to gain higher levels of understanding. In fact, this development has spurred many of the more serious and established metal detectorists to migrate to other more focused and closed Facebook groups of like-minded members.

One may worry that 'Detektor Danmark's status as the main informal meeting place and platform for conveying knowledge and culture for detectorists is deteriorating, and in this sense, it potentially weakens the coherence and stability of the 'Danish Model'. A related problem is that it may become harder for the archaeologists to monitor the trends within the Danish detectorist's community.

The growing number of detectorists has also encouraged detecting clubs located in areas with many hot spots to restrict access of new members. This is done both to protect the well-established culture of collaboration with landowners and local museums, and to protect the archaeological heritage.

There is also the increasing direct involvement of archaeologists in the local detectorist clubs, where they actively participate with advice on best practice and convey knowledge undoubtedly also to influence the orientation and culture of member detectorists. Some museums trade information about potentially find-rich areas with detectorists who have demonstrated a high level of desired behaviour to incentivise good detecting practice. The involvement of members from detectorist clubs at archaeological excavations (from which non-members are excluded) can also be used as an incentive.

There is no doubt that the Danish detector community has matured over the last three decades and become very organised in societies and informal groups, with strong friendships evolving across the country (Lyngbak 1993). But there is a risk that a growing number of detectorists are not organised within the different clubs, and as a consequence, an increasing diversity of agendas and practices may be evolving. Together with the trend of an increasing involvement of detectorists in archaeological research processes and projects, this accentuates a concern amongst some archaeologists and museums that the Danish model needs adjustments to secure there is a sufficient skill level and an understanding and propensity by Danish metal detectorists to follow the spirit of the Danish Treasure Trove. This could be adjusted through stricter regulation, compulsory courses and certification for example.

A more formalised national body to represent the Danish detectorists in the necessary dialog with the museums, authorities, and politicians could also be required. Up until very recently, the DAA had been unwilling to take on that role even though most detecting clubs are listed as members. A recent general assembly suggests that this may hopefully will change in the future. It is crucial that a balanced approach is found whereby the many positive characteristics of the Danish Model are preserved while also supporting the growing use of metal detection as an integral part of archaeological research and knowledge building.

On the side of archaeology, there seems to be a need to develop scientifically verified methods for metal detecting applied in archaeological investigations and research. Maybe these methods could even be an integral part of archaeological studies (see Aagaard et al.2025 in this special issue). As metal detecting increasingly occupies a prominent role in Danish archaeology alongside developer-funded excavations, it is apparent that it should eventually be reflected in the curriculum of the country's two archaeological education institutions. Currently, the focus of artefact education often revolves around settlement, burial, and votive/deposit finds, with loose finds receiving comparatively less attention. However, many artefacts are significantly affected by their exposure in the plough layer, which often results in fragmentation to varying degrees and surface alteration due to oxygen, weathering, and agricultural fertilisers. A greater focus in the curriculum on such fragmented artefacts more accurately reflects the material submitted by metal detectorists to the country's museums. The sheer volume of artefacts underscores the necessity of encouraging students to engage with detector-derived material and incorporate it into their studies and research. Such an approach would establish a robust foundation for future archaeologists and their work.

One of the challenges facing the metal detecting community is how to continue accommodating new members of the hobby while expecting an increasing level of proficiency, both in terms of recording and knowledge of various artefacts. This places significant pressure on beginners and makes it difficult for them to establish themselves in the field. Experienced detectorists should remember that they themselves were once at a point where they may not have been able to distinguish a circular fibula from a round keyhole cover.

But to what extent of responsibility and what associated tasks can reasonably be placed on the shoulders of detectorists? Some museums expect extensive spreadsheets containing far more information than just a registration number and coordinates for the discovered artefacts. While we detectorists pride ourselves on excelling in citizen science, it's important to remember that citizen science hinges on voluntary participation—and the current legislation and requirements from the National Museum do not encompass track logs or GPS notes, even though it is appreciated and encouraged under the 'care' supplement. The increasing demands from many local museums can be viewed both as a result of their lack of necessary resources to carry out such tasks independently, and as a response to the growing scientific methodologies being developed and applied to metal detector finds.

The fact that certain finds are no longer classified as Danefæ, despite their age, sets a precedent for what Dobat also refers to as 'good' and 'bad' finds. Namely, those that warrant compensation and those that do not (Dobat 2013, 716-717). Over time, all of this may lead to collection biases in our collections, as many of these seemingly insignificant finds are actually markers for trading places, workshops, and settlements.

Today, initiatives like DIME serve as crucial platform bridging between metal detector users, local museums, and NatMus. The aim is to alleviate some of the emerging issues and the considerable workload that currently burdens all components of the system. Furthermore, DIME is highly appealing for beginners as it covers the most essential basic information in relation to registration: time, location, and photographs. The remaining details can be identified either by the local museum or by engaged users, with ample opportunities for learning on the sidelines.

While metal detecting is inherently an individual pursuit, much of it still occurs within a communal context. Denmark has always been characterised by a strong tradition of associations and a desire to form communities with like-minded individuals. Therefore, we believe that both beginners and the Danish model will continue to benefit from local, regional, and perhaps eventually national communities of metal detector users. Knowledge-sharing often occurs most effectively through conversation, and hands-on training by experienced detectorists is akin to having an encyclopaedia in one's pocket.

Ultimately, it boils down to time. Spending hours in the field and dedicating time to research and learning fosters skilled detectorists, and a strong community encourages enthusiasts to brave the sometimes-inclement Danish weather in pursuit of traversing the fields.

The outline of the course contents are as follows:

Metal-detecting archaeology seen from the Museums perspective.

Goals for the collaborative work between the museums and the metal detectorists:

The Danish Model at its core

Legislation

Do's and don'ts

What should be recorded and what happens to the find from when it's handed in and until the receipt of the Danefæ letter from the National Museum?

The following topics are presented by Harjas own detector users:

Permits that must be obtained before you can start detecting.

How to register finds in the field.

How do you best handle your finds before they are handed over to the museum?

Code of Ethics (interaction with other detectorists).

What to do before handing in your finds? Finds-report, finds form, search tracks etc.

Search tracks and GPS. How to make search tracks and why are search tracks so important?

Equipment that is necessary or good to have. Detecting techniques.

Where to find information about the objects you find.

A lot of information for beginners is available on Harja.dk (all in Danish).

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.