Cite this as: Recht, L., Zeman-Wisniewska, K., Clark, B. and Yamasaki, M. 2025 Excavations at Late Bronze Age Erimi-Pitharka, Cyprus: The 2024 season, Internet Archaeology 69. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.69.1

Following two seasons of excavation in 2022 and 2023, a third season took place at Erimi-Pitharka in May 2024, focused on expanding work in the eastern trenches. The objective of this most recent season was to better understand the Area I/1A building complex and to further expose spaces partially uncovered in the 2022 trenches (T5, T6). Four new trenches (T9, T10, T11, and T12) were opened to follow the walls uncovered in previous seasons. These excavations revealed additional sections of the large building complex and offer new insights into the architectural and functional aspects of the site. We here report the preliminary results of the 2024 season, including further analysis of the role of Erimi-Pitharka in the Kouris Valley in the Late Bronze Age.

Erimi-Pitharka (hereafter Pitharka) is located in the village of Erimi, in the Kouris Valley in Limassol District of Cyprus, about 100-110 metres above sea level (map). The site is located on the eastern bank of the now-dry Kouris River (drained due to a modern dam about five km to the north); the valley encompasses numerous archaeological sites with a broad chronological range (for overviews of sites and surveys, see e.g. Violaris 2012; Bombardieri and Chelazzi 2015; Kopanias et al. 2022; for a chronological table of the prehistoric and protohistoric period in Cyprus and Levant, see Recht and Bürge 2023, table 1.1). Sites in the nearby area include Erimi-Pamboula, Erimi-Kafkalla, Erimi-Laonin tou Porakou, Episkopi-Bamboula, Episkopi-Phaneromeni and Alassa. The Chalcolithic site of Erimi-Pamboula, was excavated by Dikaios in the 1930s (Dikaios 1934) and published later in detail by Bolger (1988). Since its discovery, it has been an eponymous site for the so-called Erimi culture, currently incorporated into the Chalcolithic archaeological sequence of Cyprus (c. 4000-2400 BCE). The Middle Cypriot settlement, workshop area and cemetery of Erimi-Laonin tou Porakou is located a few kilometres north of Pitharka, on a high plateau on the eastern riverbank and it has been excavated since 2008 by an Italian Mission (Bombardieri 2017).

Erimi-Kafkalla, used mainly as a cemetery in the Early and Middle Cypriot Period, also contains evidence of Late Cypriot tombs and a number of installations dated to the Late Cypriot period (Belgiorno 2005; Violaris 2012). North of Pitharka (located near the modern Kouris Dam), and most relevant to the contemporary landscape of Pitharka, is the site of Alassa (Paliotaverna and Pano Mantilaris; Hadjisavvas 2017). Alassa, the urban centre dated to the LC IIC-IIIA, is famous for its ashlar masonry, storage, and olive oil and wine production (Hadjisavvas and Chaniotis 2012). Also from the Late Cypriot period, the western bank of the river was home to Episkopi-Phaneromeni, a small LC IA settlement with some earlier material (Carpenter 1981; Swiny 1986) and Episkopi-Bamboula, a settlement and cemetery dated to LC IA-IIIA (c. 1600-1150 BCE, Benson 1972; Weinberg 1983). All of these sites are within walking distance and must have had close contact during their occupation, but their exact relationship is not fully understood.

Pitharka has previously been excavated by the Department of Antiquities Cyprus, initially after a subterranean complex was discovered during construction activities in 2001, and subsequently in rescue excavations from 2007-2012. These excavations have been published in short preliminary reports (Vassiliou and Stylianou 2004; Flourentzos 2010; Papanikolaou 2012; see also Recht et al. 2024 for more details of the results from this earlier work and its relation to the new excavations). Since 2022 new excavations have been carried out by the University of Graz in collaboration with Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University, Warsaw, directed by Lærke Recht and co-directed by Katarzyna Zeman-Wiśniewska.

The 2007-2012 excavations were conducted in four areas, labelled I-IV. All areas contained workshop installations, and in some there were terrace/retainer walls, but the area of particular interest here is Area I. Here, a large complex with stone foundations and a mudbrick superstructure, possibly an administrative building, was excavated (Papanikolaou 2012, fig. 1).

The rooms of the complex were laid out in two rows, with successive stages of construction. The finds include a terracotta drain, stone tools, metal objects, human and animal remains, and pottery dated to LC IIC-IIIA (ca. 1300-1150 BCE) (Papanikolaou 2012, 313). The new excavations have focused on this large complex in Area I, with new trenches set immediately outside the area of the department excavations (marked by a modern cement wall, now removed); this area is labelled Area 1A to show both its connection with the building and to differentiate the new trenches. The aim has been, and continues to be, to better understand the nature of the entire complex, including its extent and function in relation to the overall role of Pitharka in the Kouris Valley in the Late Bronze Age.

In 2022 and 2023 twelve trenches were laid out north and east of Area I. The first two seasons demonstrated that the building indeed continued in both directions, with walls connecting to previously detected rooms, this significantly extended the known boundaries of the complex. In both directions, there are sectors consisting of rooms, passageways, interior and exterior spaces that were used for installations and industrial areas. They also demonstrated that the stratigraphy is deeper than first anticipated, though still relatively shallow, with the remains usually appearing very close to the surface and sometimes disturbed or partly destroyed by modern building activity in the area. Many of the rooms and features were semi-subterranean, with the inhabitants making full use of the bedrock by carving into it. The finds primarily consist of ceramic sherds and worked stone objects, and the forms seem mainly related to agricultural production. It appears that the entire area was peacefully abandoned as most light movable material was cleared out while heavier and/or broken objects such as pithoi, bathtubs and worked stones were left behind.

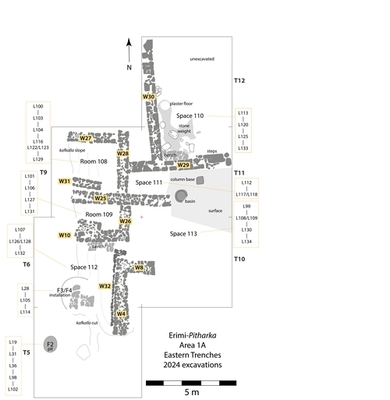

During May 2024, a third season of excavations was carried out at Pitharka. The excavations focused on continuing and expanding work in the eastern trenches opened in 2022, with the specific aim of uncovering the spaces suggested by walls in the northern and eastern part of Trench 6, completing the excavation of a pit in Trench 5, and the overall aim of identifying the limits and further understanding the nature of the Area I/1A building complex in this area. Trenches 5 and 6 were further explored, and four new 5 x 5 m trenches were opened in order to follow the walls initially uncovered and any new ones that appeared during the season: Trenches 9, 10, 11 and 12 (Figure 1a-b).

Overall, the area reveals an additional sector of the Area I/1A large building complex discovered in earlier excavations by the Department of Antiquities in 2007-2012 (Papanikolaou 2012) and expanded in the new excavations since 2022 (Recht et al. 2024). This sector includes several rooms of various sizes and depths, along with open and semi-open spaces. As seen elsewhere for this building, many of the spaces were constructed using a combination of cutting into the natural bedrock (locally known as kafkalla), drystone walls and upper mudbrick walls. All the mudbrick walls have collapsed into the rooms, and the mudbrick itself has largely deteriorated, but many of the stone walls are still intact, and the cuts in the kafkalla can often still be identified. The stone walls are generally 60-80 cm wide and constructed using large stones for the outer faces and smaller stones for fill in between. They are usually well-constructed, some of carefully cut stones (see discussion of Space 110, below) but others are less well-made and there is some evidence of attempts to repair and support walls (see also Recht and Zeman-Wisniewska forthcoming). Somewhat surprisingly, the walls are mostly built abutting each other; very few actually intersect. Nearly all of the walls are very close to the modern surface, and some have sustained damage from modern activities in the area.

Some spaces also have extensive stone and mudbrick collapse, presumably from walls, although rubble from elsewhere or even deliberate deposition cannot be ruled out, especially given the volume and density of the rubble in some spaces. This is in line with the findings from the northern trenches excavated in 2023 (Recht et al. 2024). Throughout the complex, the kafkalla has been used in various ways: to delimit rooms and spaces, to serve as the cut for pits and other features, and to create spaces that were semi-subterranean, presumably in order to maintain a more stable temperature and protect from light and weather. In addition, the calcareous soil was used as fills, and especially to consolidate exterior surfaces.

While most spaces still appear to have been largely emptied, as observed in previous seasons, the 2024 campaign yielded substantially higher concentrations of finds, with more stone objects and ceramic sherds than the combined 2022 and 2023 assemblage counts. These add to the types already known, such as grinding stones and slabs, a remarkable number of stone vessel fragments, so-called gaming stones, along with a stone axe and a stone weight. The ceramics continue to be dominated by Pithos, Plain White and Cooking/Coarse wares, but with an expanded repertoire of shapes, and with the occurrence of wares not previously identified, such as Monochrome, Black Slip, Red Slip, Bucchero and White Shaved wares. Other types of finds are rare, but include textile tools, part of a zoomorphic figurine, and a bronze chisel. Overall, the finds continue to support the impression of Pitharka as a regional centre focusing on agricultural produce.

Based on the finds, Pitharka can be dated to the LC IIC - IIIA period (13th and first half of the 12th century BCE), in accordance with previous results. This is especially evidenced by the fine ware pottery, which includes Base Ring, White Slip, White Painted Wheelmade and Aegean-type wares. Below the colluvial soil and top cultural layer, the archaeological contexts are fairly secure, and there is little disturbance from later periods. The stratigraphy, architecture, features and surfaces demonstrate several phases at Pitharka, but these all lie within the LC IIC - IIIA period. However, the occurrence of sherds dated to the Neolithic period, while occurring in a mixed context, could suggest an earlier presence in this period somewhere in the vicinity of Pitharka. The site appears to have been peacefully abandoned: there is much collapse of walls, but no evidence of extensive burnt destruction. Rooms and spaces have generally been emptied of the expected unbroken and valuable objects, with the finds mainly consisting of ceramic sherds and less mobile and broken items such as pithoi and groundstone tools, suggesting that the inhabitants had ample time to leave the site.

The 2024 excavated area of the complex can be divided into connected but distinct interior rooms and open or semi-open spaces. These are described below in detail. While some spaces and features have been fully excavated, others still require further exploration, and the analysis offered here should thus be understood as preliminary.

Room 108 and Room 109

Room 108 and Room 109 are located in the northwest corner of the excavated area, with Room 109 immediately south of Room 108 (Figure 1b and Figure 2; Model 1). Both are fairly small spaces with drystone walls to the north, east and south, but their western borders consist of sloping bedrock, and the walls have been constructed along this slope. This integration and use of the bedrock in the architecture of the site seems to have been a consistent strategy which can be detected in several variations, including for surfaces, parts of walls, to create semi-subterranean rooms and entirely subterranean structures (Recht and Zeman-Wisniewska forthcoming).

In the case of these two rooms, the walls reach a depth of about 60-80 cm, after which they were constructed on top of a mix of soil and deteriorated mudbrick material. The only exception to this is the eastern wall of Room 109 (Wall 26), which has a depth of at least 92 cm (not fully excavated). No floors or surfaces were preserved in either room, but the layers below the walls suggest an earlier phase. Room 108 is 2.90-2.40 x 2.80 m at the top of the walls, but the space must have been constricted by the sloping kafkalla; the same applies to Room 109, which is also 2.40 m broad (from west to east), but significantly narrower with only 1.40 m from north to south. The outline of Room 109 has the additional oddity of Wall 10, which has a typical wall thickness of 68 cm in its eastern part but is 110 cm in the west, thus significantly decreasing the available space, and the entrance into it.

In Room 108, the uppermost layers (L100, L103, L104; Figure 2a) contained some pottery, with a concentration of finds in the southeastern corner: this is also where part of a terracotta animal figurine was discovered (L103 FN24, Figure 9.6; Model 2), along with parts of wall brackets (Figure 7a.11-12) and a few animal bones. A small shallow circular concentration of stones in this part of the room may have served as some kind of installation. Large and medium-sized stones had been lodged against Wall 27 perhaps to support the wall, a practice also identified in the northern trenches or, in the case of a large and nearly flat stone placed in the corner, as part of another installation. There is likely to have been a surface at this level, although this was not preserved.

At a lower level (L116), another wall became visible (Wall 31) (Figure 2a). This wall, running roughly from west to east, also follows the slope of the kafkalla, and its bottom course of stones is roughly at the same level as that of Wall 25 and Wall 27. It is immediately adjacent though not entirely parallel to Wall 25 and extends for 1.65 m into the room. Since it does not connect to any other walls and is in a slightly different alignment (but at the same level), the function of this wall is not clear; it is possible that it was a bench, though it was not built directly against Wall 25.

Finally, the loci below the walls (L122, L123, L129; Figure 2a) must represent earlier phases in the occupation of the site, although still lying within the LC IIC - IIIA period. A line of reddish-brown soil along Wall 27 suggests a possible foundation trench for the wall, but this was not identifiable for the other walls. Loci 122 and 123 may thus represent a preparatory lower fill on which to build the walls. However, below these, in the eastern part of the room, there was a pit, partly cut into the kafkalla, measuring c. 100 x 60 cm and at least 70 cm deep (L129). Its purpose is not clear, but it was lined with stones and vertically placed ceramic sherds; no other finds were recovered from it. Stratigraphically below the fill and walls of Room 108 it pre-dates that room and demonstrates an earlier use of the space.

Beside the terracotta figurine, the finds from Room 108 include two worked stones, a chipped stone, and a slightly higher than usual concentration of pottery. The pottery here is interesting in that it includes part of a miniature imported Mycenaean vessel (Figure 7b.19), sherds of Proto-White Slip and White Slip I ware (Figure 7b.8,10,11), and several wall brackets (Figure 7a.11-12). Some parts of pithoi could also be restored.

There were no clearly preserved floors in Room 109, but its use-surface may have corresponded to that of Room 108. The low concentration of finds in the room does not reveal its function. The highest layers (L101, L106; Figure 2b) consisted of a concentration of stones in the western part of the room - this was first believed to be from wall collapse, but their density and placement (with an empty 'channel' along Wall 10) suggest a more deliberately created installation. Below these layers, the beginning of Locus 127 included a small area of flat-lying pottery that could indicate a surface, but without a change in the soil. The lowest layer (L131) is below Wall 25 and Wall 10, but associated with Wall 26, and presumably with the lowest layers in Room 108 (Figure 2b).

Overall, the room contained a relatively low volume of pottery, mostly Plain White, Pithos and Cooking/Coarse wares, with some fine wares (including White Shaved, Base Ring, White Slip and Aegean-type). There were also a few worked stones (grinding slabs) and animal bones.

Space 110

Space 110 is a large space, probably a room, covering much of Trenches 11 and 12 (Figure 1b, Figure 3, Figure 4; Model 1). As the walls extend outside the excavated area, the exact limits are not yet known, but it is already clear that it is larger than any other room as yet uncovered at Pitharka (at least 4.30 x 3.80 m). It is limited by Wall 29 to the south, and Wall 30 to the west. Both these walls continue into the unexcavated sections of Trench 11 towards the east, and Trench 12 towards the north. The walls are extremely well-built of large stones that have all been cut flat on both faces; some of these have a depth of at least 45 cm. Wall 29 abuts Wall 28 and must at some point have been in use at the same time. However, both Wall 29 and Wall 30 are in a slightly different alignment than the other walls of the area, which could indicate that they were built in a later phase.

The top layers of this space were characterised by an extensive and rather dense collapse of stones, along with deteriorated mudbrick material (L113, L120, L125; Figure 3). The stones in this collapse were mostly quite large and very densely packed, particularly in the northern and northeastern parts. In the southeast, there were fewer stones but an intense layer of mudbrick material, perhaps the remains of a badly preserved installation. The stone rubble included a high amount of pithos sherds, along with eight worked stones (including a large gaming stone, grinding slabs, pestle, pivot stone and a stone basin; Figure 4a). In the northeast, as part of this collapse, there were several vessels that appear to have fallen with or under the stones. Many sherds of two pithos rims and necks were found together, some placed vertically (Figure 4b.1-2); just north of these was a Canaanite jar, lying on its side and almost complete below the shoulder, but crushed by the stone rubble (Figure 4c.8).

Space 110 has a number of interesting features. At the eastern end of the excavated part of Wall 29, there is a one-metre-long threshold stone, and immediately below this, a neat step into the room, formed by another long stone of c. 1.10 m (Figure 1b and Figure 3). A small gaming stone had also been re-used to form part of the threshold (W29-ST1). Against Wall 29, in the corner with Wall 30, there is a stone-built bench, roughly 1.5 m long. Below the dense stone layer, a plaster floor was found partly preserved in the western part of the room (L133; Figure 3). There are several circular areas in the floor that appear to have been deliberately created (they are quite regular, and the plaster slopes into them), presumably related to installations no longer present. In the eastern part this floor is not preserved. The space may have been related to agricultural production: on the floor there was a stone weight from a press (probably olive) (Figure 4a.12), a stone mortar (Figure 4a.8) and a stone pestle, along with a pecking stone (Figure 4a.1), all placed near each other towards the corner and bench.

The space was not fully excavated, neither in its extent nor in its depth. Given the obvious importance of this very large room, one of the main aims of the next campaign is to determine these boundaries. There can be no doubt that Space 110 was a room of significance, with a more formal structure and greater attention paid to its size, appearance and access. The walls here are clearly more carefully made than all others so far, with their ashlar-like facades and threshold with a step made of very large and cut stones. The stones of the walls are in fact so large that even the first course of stones has not been uncovered everywhere, even at a depth of 45 cm. In order to plan for future work, a small test trench was made at the northern extension of Wall 30, to attempt to determine its extent. The 2.5 m extension demonstrated that this wall continues further north, reaching also the section of the test trench (Figure 3). While this needs to be explored in greater detail, it means that the space is greater than that excavated so far, and certainly the largest interior space from the new excavations at Pitharka.

Space 112

Space 112 is south of Room 109 (Figure 1b; Model 1). It is bounded to the north by Wall 10, and to the east by Walls 4/32. There is a passageway to Space 113 in the northeastern corner, between the corners of Room 109 and Walls 4/8. To the east, the kafkalla slopes into the space in the same way as Room 108 and Room 109, and the installations of F2 and F3/F4 are placed in the south and southwest. The entire space was probably related to the use of those two installations and may have been open or semi-open. It is roughly 5.80 by 2.50 m in size.

The uppermost layer of the space was first excavated in 2022, when the top of features F3 and F4 were also discovered, and F2 was partly explored. This and the top layer excavated this season (L107) contained an average amount of pottery and some stone collapse, all mostly within deteriorated mudbrick material. Below this (L126, L128), two small concentrations of two rows of stones were found against Wall 10, which are believed to be the disturbed parts of a bench. This bench is quite shallow, consisting only of one course of stones. It is assumed to have been associated with a surface, but none was preserved.

The lowest layer (L132) contained less material, and the kafkalla continued to slope downwards with deeper excavation. This layer revealed an earlier wall below Wall 4, labelled Wall 32. Wall 32 is offset from Wall 4 by one row of stones to the east and south, but the two walls are parallel to each other (Figure 1b; see also Animation). It uses a similar, but less careful, technique with medium-sized stones, and a large cornerstone in the north, on which the corner of Wall 4 and Wall 8 is also placed. While this wall is currently not connected to the others, it clearly demonstrates an earlier use of the space.

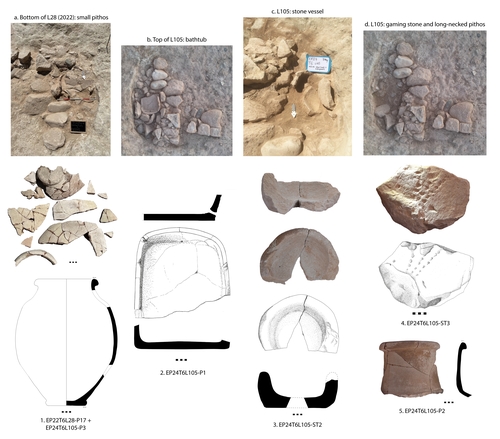

The most prominent part of Space 112 is feature F3/F4 (L105, L114), initially thought to consist of two separate installations, but now identified as part of the same feature (Figure 5). This is placed in the south/southwestern corner of the space and may in turn be associated with pit F2. As initially discovered in 2022, F3 and F4 consisted of two small platforms or stubs of walls, placed perpendicular to each other (Figure 5a; see also Recht et al. 2024, fig. 2b). Directly west of F4 was part of a so-called 'bathtub' (with about half the base and some of the lower body) apparently in situ (Figure 5b). Time did not permit full excavation of this context in previous seasons, and it was therefore a priority during this year's campaign.

It was revealed that F3/F4 is a much deeper cut in the kafkalla of at least 60 cm, and the stone 'platforms' were only the latest version of the associated installation. Crushed over and behind the bathtub, there were many sherds of a small, short-necked pithos (L28-P17, Figure 5a). Some of these were removed during the 2022 season, and additional ones, including about half the base, were removed this year. The subsequent ceramic analysis shows that almost the entire vessel was present, though very fragmented. The pithos must have fallen directly on top of the bathtub, breaking in such a way that part fell into the bathtub, and part was lodged behind.

Below the pithos and bathtub, there was a stone vessel, roughly circular in shape, and represented by two broken but large fragments (L105-ST2, Figure 5c). Below this, there was another stone object - a so-called gaming stone (L105-ST3, Figure 5d). Although incomplete, it seems to have the typical layout with three rows of indentations (usually of 10 each). Roughly at the same level, but slightly further to the north, there were again many sherds of a pithos, this time of a long-necked and larger version, with much of the neck and shoulders present (L105-P2, Figure 5d). The neck pieces had been broken and 'stacked' following the curve of the neck, suggesting a deliberate deposit. Another pithos base was found below this, partly in the western section of the cut in the kafkalla, of the same type as the one associated with the bathtub.

The cut of the installation where all of these objects were placed was partly lined with stones, and there was a filling of stone rubble below them, consisting mainly of lumps of limestone. This rubble fill continues below the stone 'platforms' of F3/F4. It could belong to an earlier use of the entire installation, which itself is a larger U-shaped cut into the western edge of the kafkalla. The function of the installation is not known, though we would hypothesise that it is related to the agricultural manufacturing activities of the site and may have been in use with feature F2.

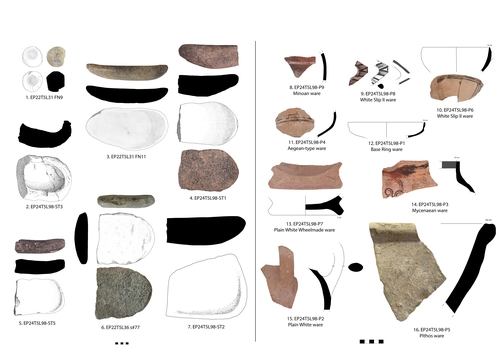

Feature F2 does not lie directly within the area of Space 112 but is mentioned here because it may have been used in conjunction with Feature F3/F4, and is located just to the southwest. F2 is a pit of c. 80 cm diameter and 1.10 m deep (L98, L102), again cut into the kafkalla. Although it may originally have been used for storage, as excavated, it had been used as a dump, primarily for stones and a few ceramics. The stones included several grinding slabs and parts of stone vessels/basins, and the ceramics were the typical assemblage of primarily pithos and Plain White ware sherds, along with some examples of local and imported fine ware (Figure 6).

Space 111 and Space 113

Space 111 was assigned to a small narrow semi-open space east of the northeastern part of Room 108. It is bounded by Wall 29 in the north, Wall 28 in the east, and Wall 25 in the south. There is no wall or other preserved boundary to the east, suggesting that this was a semi-open space. Within the walls it is 2.40 by 1.15 m in size. The room was only excavated to a depth of about 10 cm, and the depth of the walls is thus not known but given the shared walls of Wall 25 and Wall 28 with Room 108 and Room 109, it seems likely that it was in use at the same time and perhaps had a similar floor level. It was not fully excavated due to the associated contexts immediately to the east, with an embedded stone basin and plaster floor (see below), where it was deemed more appropriate to preserve this overall context rather than excavate deeper in this particular space. As excavated, the space was relatively empty and only contained a small amount of pottery in the two related loci (L112, L117).

Space 113 is the most complex and in some ways the most fascinating of those excavated this season. It may in fact constitute more than one room, but until more details are known from further excavation, it is described here as a single space. It is a partly open and partly semi-open area. It is delimited by Wall 29 to the north, and Walls 26 and 4 to the west, with the corridor providing access to Space 112 between them. In the west, Walls 8 and 25 extend into the area, creating semi-open spaces similar to, but less contained than, that of Space 111. In the east, the area is most likely an open courtyard which once had a limestone-based surface (surfaces at Pitharka were often made using a mix of crushed kafkalla, at times making it challenging to differentiate these surfaces from the kafkalla itself). The area of the open courtyard (L99, L108, L109, L110; Figure 1b) yielded an unusually high concentration of pottery relative to the norm at Pitharka, including some unusual pieces (see various examples from these loci on Figure 7).

Space 113 is extremely interesting for a number of reasons. Firstly, in the northeastern part, there is the clear white surface, or rather sub-floor; this can be traced all the way to a square column base which is directly outside the threshold with a step into Space 110 (Figure 1b; Model 1). Just southwest of this, and immediately in front of the edge of Wall 25, a round stone basin had been embedded in this surface. The basin is nearly intact (only part of the rim missing), with an interior diameter of 55 cm and a depth of 25 cm. The surrounding surface slopes down towards the basin on all sides, and at its northern rim, a small patch of plaster floor illustrates how the original floor had covered the area and part of the rim of the basin. This overall context suggests an installation related to liquids meant to flow into the stone basin, although there is no drain away from the basin itself.

Secondly, the area between Walls 8, 26 and 25 (with the passage into Space 112) was investigated to a deeper level (L130, L134). In its upper loci (L99, L109, L111, L115, L121), there was another dense concentration of stones, possibly related to collapse, but another 'channel' empty of stones along Wall 8, similar to that in Room 109, and the density of material, could suggest a more deliberate deposit. In the corner of Walls 25 and 26, close to the modern surface, was a Canaanite-type jar, lying on its side. It had been crushed, both by stones from below, and from above, likely from modern activities at the site. Nevertheless, most of the body up to the shoulders could be recovered and restored enough to determine a profile (Figure 7c.5).

In the lower layers of the area (L130, L134, L134F), Walls 8 and 25 were not yet in use, but Wall 26, possibly with Wall 32, was used. At this level (L134), a large and uneven white kafkalla-like area appeared, along with a cut in its eastern extent (L134F). The cut in the white patch is clear in the east and was lined with ceramic sherds in the remaining part. It was filled with large stones and pithos sherds, and at the top, there were many large pithos body sherds belonging to the same small pithos. The cut is not yet fully excavated but appears to be another pit using the kafkalla as at least part of its outline. Loci 130 and 134 continued to contain high levels of ceramic sherds; for Locus 134, this includes some sherds pre-dating the known dates of the settlement: these all appear to belong to the Ceramic Neolithic of Cyprus (see below and Figure 8).

Although not directly connected by walls to the rooms excavated in 2023 and 2022, and those excavated previously by the department, these rooms and spaces are surely part of the same large building complex that occupies Area I/1A. It is possible that the building consisted of adjacent and connected but distinct sectors, and that the units described here are part of one such sector. This can only be fully understood when the entire building has been delimited. With the currently excavated trenches, we can say that these spaces are connected by open spaces with kafkalla-surfaces, and by various kafkalla-cut installations and features.

The entire building seems, as also proposed by Katerina Papanikolaou for the earlier excavations, to be the central structure of the site, focused on industrial activities related to agricultural production and storage (Papanikolaou 2012). There is as yet no evidence of the building being used for domestic purposes, making this a workshop and administrative complex rather than a living space. The preponderance of large storage vessels, stone tools and objects related to agricultural products, and the installations and finds related to storage and processing of grain, olives and grapes continues to solidify Pitharka as a regional agricultural centre of storage and production. That the Area I/1A complex was the primary building of the settlement, perhaps administering and distributing its products, is suggested by its location, overall size, room sizes, and the formality of some structures.

The results of the 2024 season do not alter the main occupational period of Pitharka, which is still dated to LC IIC - LC IIIA. All the structures uncovered belong to this period, but the phases and sequences of construction can be detected within this, as can some sequences of events, at least within spaces and sectors. The architecture suggests two main phases: one that pre-dates all stone walls, with the possible exception of Wall 32 and Wall 26; and another that includes use of all walls on Figure 1b except Wall 32. The two phases must be chronologically very close, since there is no significant discernible difference in the associated finds. A sequence can also be suggested for the construction of the walls, as illustrated in the animation. This is a hypothetical reconstruction, based on the building technique, relations and depth of the walls. Importantly, it should be noted that many of these walls are likely to have been built immediately after each other, with no great gap in time - again with the possible exception of Wall 32 and Wall 26, whose alignment and depth suggest an earlier phase and different layout of the space.

At least two separate 'events' can also be identified as belonging within the latest phase - understood not as single points in time, but occurrences or more prolonged uses of the spaces. The first of these is the use of the entire sector and its installations related to production and storage. In this, the room of Space 110 would have been used for industrial activities, perhaps related to olive oil production, and Space 113 with its plaster surface, column base and embedded stone basin would have provided an open or semi-open courtyard for additional production. After this, and marking a second use or 'event', most of the area suffered from collapse of the upper walls of the building, with mudbrick material and stone rubble falling, crushing finds, and covering especially interior spaces; some rubble may also have been intentionally deposited. The lack of unbroken, complete and more valuable objects makes it likely that the sector was at least partly abandoned prior to the collapse of the structures. This was followed by a complete abandonment of the use of the sector.

The 2024 season at Pitharka produced significantly more pottery than the previous 2022 and 2023 seasons combined (3791 sherds total from 2022 and 2023). Over 5000 ceramic sherds were recorded in 2024. The increase in material is due to certain spaces (e.g. Space 110, Space 113) producing very high concentrations of pottery. Preliminary analysis of the material shows that, similar to 2022 and 2023 (see Clark and Recht forthcoming; Recht et al. 2024), the vast majority of wares belong to Pithos ware and Plain White ware, and lower proportions of Cooking /Coarse ware. Finewares are also well represented, in smaller quantities (11% of the overall material), but with a significantly higher proportion than the 2022 and 2023 seasons. The finewares uncovered include Base Ring, White Slip, White Painted Wheelmade, Aegean-type, Black Slip, Red Slip, White Shaved, Red Lustrous and Monochrome wares. There are also imported wares in the form of Mycenaean and Minoan sherds, and so-called 'Canaanite' jars.

The majority of the ceramic material can comfortably be dated to LC IIC-IIIA. The overall assemblage, dominated by Plain White and Pithos wares, support the identification of Pitharka as a site dedicated to agricultural storage and production. Almost a third of the entire ceramic assemblage (31%, 1618 sherds) comes from pithoi. According to the typology established by Keswani (1989; 2017), the pithoi can be divided into three main groups based on size and neck-type, all of which have been identified at Pitharka: Group 1, short-necked with a wide opening (e.g. Figure 4b.3), Group 2, long necked with comparatively restricted opening (e.g. Figure 4b.1,2,4,5), and Group 3, long-necked 'mega' pithoi with wall thickness of more than 3 cm. Several sherds with a wall thickness of over 3 cm (some as thick as 4.1 cm), have been identified, indicating a pithos with a volume of up to 1000 litres (Keswani 2017, 382). Similarly, a range of decorations has been noted, including with both wavy and straight applied plastic bands (Figure 4b.6). There are also examples of dark bitumen-like paint applied over or between the plastic bands.

At Pitharka, as at most Late Cypriot sites, Plain White ware is the most frequent type of ware collected. It is characterised by a huge variety of fabrics, with a range of colours, coarseness and manufacturing techniques (Eriksson 2007, 51-53). From the 2024 season, 43% (2237 sherds) of all material collected was identified as Plain White ware. Based on the diagnostic sherds, roughly 77% of the Plain White ware sherds belong to large and medium-sized closed vessels (jars and jugs) intended for storage (Figure 6.13, 6.15; Figure 7a.14, 7a.16; Figure 4c.5 with an incised post-firing +-shaped potmark). However, other shapes such as small jugs/jars, juglets, kraters, basins and bowls of all sizes are also represented (Figure 4c.3; Figure 7a.13, 7a.15).

Also identified at Pitharka and made of similar clay fired in a similar manner, which may be part of permanent or semi-permanent installation, are deep oval basins known as 'bathtubs', often constructed of clay or limestone and sometimes with a plaster lining (Mazow 2008, 291). There are also some large circular conical basins with straight or slightly curved walls, a flat base and two vertical handles (Bürge and Fischer 2018, 218). Fifteen examples (including three bathtubs and nine basins, mostly identified via rims) were identified in the 2024 season, including the excavation of the bottom half of a bathtub (Figure 5b). Additional examples include a sherd with an outlet 'plug' hole (L130-P14) and a basin sherd with two mending holes (Figure 7a.10). As with the embedded pithos from Trench 3 (Recht et al. 2024), the basin here seems to have been part of a permanent or semi-permanent installation involving liquid-related production (as also indicated by the other finds; Figure 5), and they sometimes appear in industrial contexts that suggest use in the production of textiles (Mazow 2008; 2013).

Coarse ware and Cooking ware are found in relatively low concentrations at Pitharka, each representing 9% and 6% (463 and 292 sherds), respectively of the overall 2024 assemblage. Cooking ware generally indicates shapes called cooking pots, frequently found with signs of burning, while Coarse ware is used to discuss other shapes such as bowls, juglets and lamps manufactured in the same fabric. Several distinct types of cooking pots have been identified in Late Cypriot settlements (Bürge 2023). When identifiable, the cooking pots at Pitharka tend to be wheelmade and flat-based (Figure 7a.1-3), but there are also examples of handmade vessels. Notably, the assemblage includes a body sherd with a vertical ridge on a globular body, typical of LC IB/II-IIC handmade cooking pots (Figure 7a.4). Several examples of so-called baking trays (also referred to as cooking dishes or wide shallow bowls) were also identified for the first time in the 2024 season (Figure 7a.8-9).

As in previous seasons, smaller amounts of Cypriot-made finewares include Base Ring, White Slip, White Painted Wheelmade and Aegean-type (also known as White Painted Wheelmade III from Åström's 1972 typology). Base Ring ware, dated from the LC IA2 to the LC IIC/IIIA transition, accounts for 3% (166 sherds) of the total ceramics excavated in 2024. While most of the material was highly fragmented, jugs, bowls and kraters were identified. Two sherds of Base Ring I, with either incisions or applied plastic bands, were collected. Of the overall assemblage, 1% (53 sherds) are White Slip, another classic Late Cypriot ware. The majority are typical White Slip II ware (with one sherd, L98-P6, representing White Slip II 'late'; Figure 6.10). Several sherds may represent earlier variations of White Slip, including White Slip IIA and White Slip I (Figure 7b.9-12), and possibly Proto White Slip (Figure 7b.8, including an open circle motif which may be either Proto White Slip or White Slip I) (Erikkson 2007, 50-55, Figure 12; Popham 1972, 440; see below for further discussion). All other examples are White Slip II typical or mature (Figure 6.9), and come entirely from open vessels (so-called milk bowls). Additionally, smaller amounts of wares not identified previously or only occurring in very few examples include Bucchero (Figure 4c.1), Monochrome (Figure 7b.6-7), White Shaved (Figure 7c.1), Red Slip (Figure 7c.2) and Black Slip (Figure 7c.3). A highly unusual fineware vessel is represented in Figure 7c.4, which has a brownish-red slip and a sharp carination with a handle and knob sitting at the peak of the carination. The strange angle and location of the handle/knob make it difficult to determine the shape; it may come from a pilgrim flask or askos (a possible parallel may be found in Todd 1989, fig. 14 KAD 1082, 10).

Another common locally produced fineware found across Cyprus in the Late Cypriot period is White Painted Wheelmade ware, which is generally the same fabric as that of Plain White ware. At Pitharka, these sherds appear as shallow bowls, deep bowls, kraters, jars, jugs (including stirrup and three-handled piriform jars) and cups (Figure 4c.2, 4c.4, Figure 6.11, Figure 7b.13-16). Many of these are of the Aegean-type ware, so called because they closely resemble Aegean shapes, decoration and production techniques. There is also a small amount of imported Mycenaean and Minoan ware sherds (51 sherds, roughly 1%) representing the typical selection of shapes that is found on Cyprus in this period, such as piriform and stirrup jars (Figure 6.8 and Figure 7b.18-20; Figure 7b.18 with a post-firing incised potmark), bowls, cups/kylikes (Figure 7b.17) and kraters (Figure 6.14). So far, these all belong to the Late Helladic IIIA2-B/Late Minoan IIIB repertoire of shapes and decoration.

These Aegean-imported vessels demonstrate that while Pitharka is a regional site focused on agricultural production, it did indeed take part, directly or indirectly, in the extensive Late Bronze Age trade networks of the Eastern Mediterranean. The extension of this contact to the east is further indicated by material from the Levant. A few individual sherds can be added to the two 'Canaanite' jars found in Space 113 and Space 110 (Figure 4c.8 and Figure 7c.5). These may have been produced in and imported from the Levant, or locally made; analysis is currently being undertaken to identify their provenance.

As mentioned the vast majority of sherds can be dated to the LC IIC-IIIA period, with hints of earlier LC I-II represented by the White Slip ware material. However, this year's excavations also produced about a dozen sherds belonging to a much earlier time (Figure 8). These sherds all fit with the Ceramic Neolithic (fifth millennium BCE) wares of Cyprus, and include Monochrome Red Painted, Red-on-White (Figure 8.2) and Painted-and-Combed ware (Figure 8.1), and a variety of open and closed shapes are present (Joanne Clarke, pers. communication). The sherds all belong to a single context, Locus 134, the deepest excavated locus in Space 113. The context is mixed, with the usual LC IIC-IIIA sherds making up the majority of the material, and with no clear association with the architecture. The layer itself still belongs in the same period as the rest of the sector, but this assemblage does demonstrate the long tradition of occupation in the Erimi area, and possibly even at Pitharka itself.

The worked stone tools constitute the second most conspicuous class of finds from the 2024 excavation. This last season yielded a total of 63 stone artefacts, amounting to double the quantity from the previous two seasons together. These are mainly groundstone tools such as grinding slabs, grinders/pounders, pestles and pecking stones, testifying to the agricultural focus of the site, perhaps in connection to olive oil and/or wine production. Several of these have been sampled for starch granule analysis to determine more precise use.

The grinding slabs constitute about 40% of the groundstone assemblage by weight. These are characterised by a large, flat surface on the upper side of the stone, usually - but not always - presenting a notable concave surface as a result of use. These can be roughly divided into two groups based on the type of stone used: the majority of the grinding slabs are made of hard igneous rocks (i.e. gabbro and diabase; Figure 4a.7 and Figure 6.2-6), while a little less than a third are limestone (Figure 4a.15). The largest grinding slabs, weighing from c. 10 kg up to 34 kg, are all made of igneous rocks and were clearly meant as stationary objects, perhaps as part of permanent installations. The medium-weight ones (4.5 to 5.5 kg) would have still been heavy enough to be used as querns (lower stones) but also light enough to be moved with ease. The lighter objects (between 1.2 and 3.5 kg) could have been employed as one or two-handed upper stones. Both medium and light grinding slabs present a variability in the rocks used. While gabbro and diabase are well suited for the grinding of cereals, it seems unlikely that the friable limestone would have been employed in the production of foodstuff, which suggests that the two types of slabs may have been used for different purposes.

The handheld tools assemblage for the most part consists of crushing and/or percussive tools such as pestles, grinders and pecking stones. Typically the handheld tools from Pitharka present signs of being used in more than one way. A good example is L125-ST4 (Figure 4a.3), which shows a polished surface consistent with grinding, as well as pitting indicative of percussion. Similarly, the pecking stones (Figure 4a.1) could be used as hammers due to their relatively small size (max. 1 kg) as well as function as small anvils. Handheld polishing tools are present at the site in the form of small, sub-cylindrical igneous pebbles (Figure 4a.6, Figure 6.1).

Of particular interest is the stone weight found in Space 110 (Figure 3 in situ and Figure 4a.12). The weight has a roughly trapezoidal section, is c. 50 cm long and is equipped with one regular passing hole of c. 7.5 cm in diameter. This was found close to a mortar (Figure 4a.8), a handheld stone grinder (L133-ST4) and a pecking stone (L133-ST1, Figure 4a.1). The stone weight presents strong similarities with an olive oil press weight from the LC II layer at Maroni-Vournes (Cadogan 1986, 43; Hadjisavvas 1992, 21, fig. 36). Furthermore, it should be noted that the previous excavation season yielded a small press bed (L88-ST2) that presents some similarities to the olive oil press bed from Evdimou-Hasan Osman (Hadjisavvas 1992, 55, figs 91, 105), reinforcing the hypothesis of olive oil and/or wine production at the site.

Among the stone objects are also a significant number of stone vessels and basins or fragments thereof (Figure 4a.5, Figure 4a.8-11, Figure 5c, Figure 6b.2). A remarkable find is a large stone basin (Space 113, L119-ST1, Figure 1b; Model 1; note also the similar vessel found in Room 106 in 2023 - Recht et al. 2024), almost complete, measuring c. 65 cm in diameter, still in situ. Inside, three parallel wavy lines in low relief are visible in the western half of the basin, oriented N to S, but their origin still needs to be ascertained as they can be either human-made or result from natural rock formation processes (E. Souter, pers. communication). The northern edge of the basin is partly covered by the remains of a plaster floor, while a white kafkalla subfloor covers the surface surrounding the basin for a radius of c. 50 cm and extends east- and southward to the end of Trench 11. The square base of a pillar/column was exposed c.50 cm northeast of the basin at the northern edge of the kafkalla subfloor. This suggests that the plaster floor (and its related kafkalla subfloor), the basin and the column base belong to the same associated space (see also above, Space 113). The significant number of fragments of stone vessels demonstrate the common use of these objects in the manufacturing activities of Pitharka. Their weight as stone objects may indicate that they were frequently part of permanent or semi-permanent installations, such as the embedded basin in Space 113.

Other stone artefacts include two pierced limestone objects, the function of which remains unclear, an axe, a broken pivot stone (Figure 4a.14) and three gaming stones (Figure 4a.13; Figure 5d.4), which add to the five discovered in the previous seasons. One of the gaming stones (W29-ST1) was, as seen before (Recht et al. 2024, fig. 12b), embedded in a wall, and another is a rather large, regularly shaped, oblong rectangular example (L125-ST8, Figure 4a.13). Finally, one fragment of a chert blade and some chipped stone debris complete the lithics assemblage for this season.

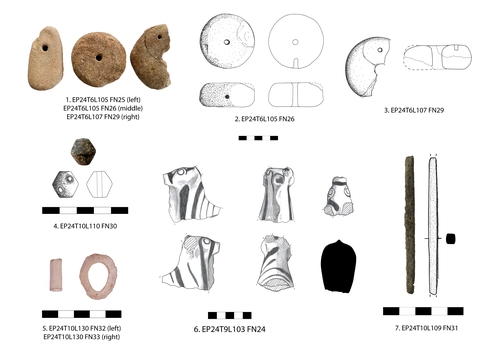

Beyond the ceramic assemblage, the clay and terracotta objects from 2024 include a number of textile tools and part of a zoomorphic figurine. Four loom weights can be added to the two examples (one short cylindrical and one pyramidal) found in previous seasons. These consist of three short cylindrical and one truncated pyramidal type (short cylindrical: FN26, FN27 and FN29; pyramidal: FN25; Figure 9.1-3) (following the typology developed by Centre for Textile Research, see Andersson Strand and Nosch 2015). They would have been used with a warp-weighted loom, but all are single finds and too few to constitute full sets for a loom. FN26 is a nearly complete terracotta short cylindrical loom weight with a weight of 171 g, FN27 is a nearly complete but very friable clay (unfired) short cylindrical loom weight with a weight of 106 g, FN29 is a broken (roughly half preserved) terracotta short cylindrical loom weight with a weight of 124 g, and FN25 is a nearly complete truncated pyramidal terracotta loom weight weighing 118 g. The short cylindrical examples from Pitharka are all pierced in the centre of the cylinder. FN26 and FN29 have additional holes, either on the flat surface or in the side of the weight, not pierced all the way through the objects; since they were made pre-firing, it seems unlikely that they are production errors, but their function remains to be fully understood (Giulia Muti, pers. communication).

All of the Pitharka examples weigh less than 200 g, meaning that they could be used with very thin to thin thread (Smith et al. 2015, 341). but short cylindrical ones can be used alone to produce denser textiles because they can be spaced more closely on the loom (Sauvage and Smith 2016, 197). Both short cylindrical and pyramidal loom weights appear at Alassa (Hadjisavvas 2017, throughout), Episkopi-Bamboula (Smith 2021) and Kition (Smith et al. 2015), and especially pyramidal shapes are common at LC II-III sites on Cyprus. The two types of weights have similar functional characteristics (Firth 2015) and can be used together as part of the same set (Smith et al. 2015, 343-344). There may be a slight chronological difference in their appearance on Cyprus. The earliest pyramidal shaped loom weights are known from LC IIA Enkomi (Muti 2024, 55), and continue to be used into the LC III period. However, the short cylindrical loom weights discovered so far from Kition, perhaps the largest Late Cypriot assemblage, belong to LC IIC-IIIA, LC IIIA and LC IIIA-B contexts (Smith et al. 2015), suggesting that this type was not used on Cyprus until late LC IIC or even LC IIIA.

Another possible textile tool is the stone biconical spindle whorl FN30 (Figure 9.4), which is decorated with circles with dots (three on the top part and three on the bottom, alternating). As it is a very light spindle whorl (weighing only 4 g), it could be used for thin thread (see examples from Kition and Enkomi: Sauvage and Smith 2016, 198-201). Given its low weight, this object may rather be a bead, though experiments demonstrate that even such light spindle whorls could be used (Andersson Strand 2015); there is some chipping around the central piercing and edges that may also be consistent with use-wear from spinning (Smith 2021, 122).

The zoomorphic figurine FN24 (Figure 9.6; Model 2) consists of the head and neck of a bovine. It was made in Aegean-type ware and decorated with dark reddish-brown paint. The fragile ears and horn have broken off, but the undulating dewlap is clearly marked in the front. The paint mostly consists of a linear pattern, but bands around the muzzle and ear may indicate a harness, and the asymmetrical pattern on the neck and shoulder could suggest that the animal was once part of a team of bovines, perhaps pulling a cart or plough.

There are very few finds of metal or even metal scraps at Pitharka. Apart from two small and corroded lumps of copper/bronze, the only recognisable metal object from the 2024 season is FN31 (Figure 9.7). It is generally well-preserved, but somewhat corroded, and slightly broken at both ends. It is made of copper/bronze, is 9 cm long as preserved and has a square section. As a tool, this is almost certainly a chisel used for carving, cutting or engraving; another possibility is that it is a stylus for writing, but the broken ends prevent such an identification, and the square section is not a common feature of such implements, which are usually rounded in section (Papasavvas 2003, 80). A rectangular-section bronze chisel was also identified at Alassa-Pano Mantilaris (Hadjisavvas 2017, 33, PM 83).

The 2024 excavations yielded seven marine shells, two of which were worked, adding to the single marine shell found in the previous season. All the shells are worn and were collected dead on the beach, a clear indication that they were not brought to the site as food. As most of the shells present no sign of human-made modifications, it is possible that they were collected for no other reason than being aesthetically pleasing.

As for the two worked shells (Figure 9.5), the first one (FN32) is a tusk shell (Antalis dentalis) the ends of which were cut into a 2 cm segment and polished to form a bead. Tusk shell beads and necklaces are common on Cyprus and are known at least from the Chalcolithic period (e.g. Ridout-Sharpe 2006, 141-144; 2019, 302). One such necklace was found in a tomb at the nearby Middle Cypriot site of Erimi-Laonin tou Porakou (Bombardieri 2011, 87-93; Reese and Yamasaki 2017, 322-323, fig. 13.8). The second worked shell (FN33) is a limpet (Patella caerulea). The apex of the shell was cut off and polished to obtain a ring-like shape, possibly used in personal ornamentation. Once again, we find a similarly worked shell at Erimi-Laonin tou Porakou (M. Yamasaki, personal observation).

The 2024 excavations at Late Bronze Age Erimi-Pitharka continued to explore the Area I/1A complex at the topographical high point of the site. The building is extensive, and its limits are yet to be identified. The focus was on a sector in the eastern Trenches 5, 6, 9, 10, 11 and 12, where there is another sequence of exterior and interior spaces. There is further evidence of the use of the local bedrock, the kafkalla, to create semi-subterranean rooms and features. Several installations may relate to workshop or production activities. The dominance of groundstone tools and stone vessels, along with finds such as a large stone weight for olive oil production (in addition to the previous find of a stone press) indicate a site preoccupied with processing and administration of agricultural products. This is further supported by the ceramic assemblage, which primarily consists of large vessels related to storage and production.

The sector represented by the excavated spaces connects to, and is part of, the large building complex in Area I/1A. Some of the walls excavated are formal, in particular those of Space 110, with a large threshold and step, and marking the largest room as yet discovered at the site. All the architecture, features and stratigraphy belong to the LC IIC-IIIA period and the sequences of walls and use of spaces can be identified within this period, likely indicating continuous habitation of Pitharka. Hints of a much earlier Neolithic presence at Pitharka or in the Erimi area can be found in the form of a small assemblage of Ceramic Neolithic sherds.

The 2024 excavations were carried out by an international team of staff and students: Brigid Clark, Emma de Koning, Lukas Gran, Eirini Paizi, Lærke Recht, Carl Sanfilipo, Marina Schutti, Emilio Semidei, Mari Yamasaki, and with shorter stays by Yasmin Nasr Martins Amar, Jackson Morphew, Amy O'Keeffe, Elina Siceva and Franciska Treiliha. Soil, phytolith and starch granule samples taken during the campaign are being analysed by The Cyprus Institute (Evi Margaritis, Kyriaki Tsirtsi, Panagiotis Koullouros and Georgia Kasapidou). The Erimi Pitharka Archaeological Project is run by the University of Graz (director Prof. Lærke Recht) in collaboration with Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University, Warsaw (co-director Dr. Katarzyna Zeman-Wiśniewska). We are grateful to the Director of Antiquities, Giorgos Georgiou, for permission to conduct excavations at Erimi-Pitharka, and the to members of the Department of Antiquities, the District Archaeological Museum of Limassol and the local Museum of Kourion (Episkopi) for their support and advice, especially Katharina Papanikolaou, Demetra Aristotelous and Elena Stylianou. We are also grateful to the Municipality of Erimi and Episkopi for their support and generous hospitality. Practical and administrative support was provided by the Institute of Classics, University of Graz (with special thanks to Manfred Lehner and Sabine Sturmann), and by The International Institute of Mesopotamian Area Studies (IIMAS). Finally, we wish to thank a number of people who have offered valuable scientific advice during the excavations and in the preparation of this article: Artemis Georgiou (ceramics), Lisa Graham and Rafael Laoutari (Chalcolithic pottery), Joanne Clarke (identification of Neolithic pottery), Ellon Souter (groundstone tools), Sophocles Hadjisavvas (olive oil and wine production), and Giulia Muti (textile tools).

The 2024 excavation was funded by the University of Graz (Institute of Classics and Office of International Affairs) and a Rust Family Foundation Grant. Additional support was provided by the International Graduate School 'Resonant Self-World Relations in Ancient and Modern Socio-Religious Practices' (University of Graz/University of Erfurt), Polonez BIS grant 2021/43/P/HS3/01355, co-funded by the National Science Centre and the European Union Framework Programme for Research and Innovation Horizon 2020 under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 945339 (PCMA, University of Warsaw), and Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University, Warsaw.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.