Cite this as: Bohling, S. 2025 Online dissemination of 3D bioarchaeological data: An exploration of ethics, user preferences, and contextualisation in an official digital repository setting, Internet Archaeology 69. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.69.9

Bioarchaeology is the study of human life in the past through the analysis of bones, skeletons, burials, and cemeteries using a contextualised, interdisciplinary approach which can incorporate biological, osteological, biomolecular, archaeological, funerary, and sociocultural data (Knüsel 2010). Applications of digital recording techniques such as photogrammetry, radiography, surface laser scanning, structured light scanning, and CT/MRI scanning are increasingly utilised as new lines of enquiry within the field of bioarchaeology (Hassett 2018; Ulguim 2018b; BABAO 2019c; Errickson and Thompson 2019; Wrobel et al. 2019). These techniques can be used to improve excavation recording and post-excavation analyses, and 3D models have considerable value in curation, research, teaching, and outreach contexts (Errickson et al. 2017; White et al. 2018; BABAO 2019c; Novotny 2019; Smith and Hirst 2019; Schug et al. 2021). While ethical approaches to the excavation and analysis of physical human remains have received considerable attention (Section 2.1), professional and academic dialogue regarding how to appropriately record, share, and display digital human remains is relatively recent and more work is necessary (Márquez-Grant and Errickson 2017; Hirst et al. 2018; Errickson and Thompson 2019; Smith and Hirst 2019; Schug et al. 2021).

The first part of this paper (Section 2) discusses the unethical origins of the field of physical bioarchaeology, demonstrating why discussion regarding the ethics of digital bioarchaeology is essential. Next, the paper addresses why the creation and dissemination of digital bioarchaeological data are important and how the output can be used and highlights the main ethical issues that have been previously raised by experts in the field. With this background established, the second part of the paper introduces the Archaeology Data Service (ADS), a CoreTrustSeal accredited digital repository for archaeological and historic environmental data based at the University of York in the United Kingdom (Section 3). As the ADS becomes increasingly responsible for the curation of digital bioarchaeological data, establishing a protocol which takes into consideration the ethical issues raised regarding this type of sensitive data is important. The second part of this paper explains the methodology of the author's MSc Digital Archaeology research project which combined the opinions of potential ADS users and best practice standards advocated for in the existing literature to develop suggestions for the dissemination of digital bioarchaeological data by the ADS in the future (Sections 3–6).

The bioarchaeological analysis of human remains from archaeological contexts is an invaluable method by which we can learn about life and death in past societies. Macroscopic osteological analysis is used to gather data about age, sex, stature, ancestry, and disease (see Ortner 2003; White and Folkens 2005; Mitchell and Brickley 2017), while biomolecular analyses offer information regarding diet (e.g. Kennett et al. 2020), physiological stress (e.g. O'Donoghue et al. 2021), disease (e.g. Pfrengle et al. 2021), and movement/migration (e.g. Gretzinger et al. 2022). If these scientific analyses are combined with historical, archaeological, funerary, documentary, and clinical research, and are considered alongside broader theoretical approaches to understanding the past, they can be used to explore a variety of aspects of life in the past.

Standard bioarchaeological analysis involves the physical handling of human skeletal remains from archaeological contexts along with measurements, photography, and sometimes destructive analysis for ancient DNA or isotopic analyses. As bioarchaeologists are studying the remains of once living people, ethical standards are essential (Squires et al. 2019). Although this paper will not address the history of bioarchaeology and the large-scale collection of human remains in depth, it is necessary to briefly acknowledge the unethical, racist, and class-based origins of this field of study (DeWitte 2015; Schug et al. 2021), origins which demonstrate why ethical standards today are vital.

With the establishment of new medical schools in the 18th/19th centuries and the desire to improve medical and anatomical knowledge, there was an increase in 'body snatching' which was used to secure recently dead cadavers for study (DeWitte 2015). In the United States, the bodies of enslaved African Americans were commonly sold or robbed from their graves and were "the primary source of cadavers in medical education" (Halperin 2007, 492). Similarly, in the 19th century, Native American remains were stolen and targeted for collection (DeWitte 2015). The consequences of these actions are still palpable today: the majority of the human skeletal remains held by modern museums in the United States are of Native American origin despite the fact that Native Americans are a minority group (DeWitte 2015).

In the United Kingdom, the collection of human remains was common in territories that once belonged to the British Empire (DeWitte 2015). A scoping survey for the Ministerial Working Group on Human Remains found that of the c.61,000 human remains held by British museums, over 15,000 were from overseas (including Africa, Asia, the Americas, Australia/Tasmania, New Zealand, Europe, Greenland, the Middle East, and the Pacific) (Weeks and Bott 2003; Jenkins 2011, 3). As in the United States, body snatching in the United Kingdom disproportionately affected disenfranchised or marginalised groups (Richardson 2001; Mitchell et al. 2011). The Anatomy Act of 1832 made it legal for the unclaimed bodies of the poor who died in workhouses or hospitals to be used for medical dissection (Mitchell et al. 2011), but even before this, body snatchers targeted poorer cemeteries as pit burials were more easily accessible and provided more cadavers (Richardson 2001, 60–1).

It is clear that the large-scale collection and curation of human tissue for scientific study have origins which are now regarded as unethical, and therefore modern, legitimate, bioarchaeological analysis of human remains requires considerable ethical consideration. At a meeting of the World Archaeological Congress (WAC) in 1989, the Vermillion Accord on Human Remains was developed (WAC 1989) which emphasised that all human remains should be treated with respect. The wishes of the dead, the local community, any living relatives/descendants/guardians, and "scientific research value" should be considered, and balance between these groups must be reached in order to come to an appropriate agreement (WAC 1989). Similarly, Walker (2008, 20) established three basic guidelines for ethical analysis of human archaeological remains: 1) researchers should afford dignity and respect to the remains of the once-living people they are studying, 2) descendant groups should be able to control what happens to the remains of their ancestors, and 3) archaeological human remains should be curated as they reveal unique information about the past.

These principles have been addressed and expanded upon in the publication of formal guidelines for best practice with regards to the excavation, analysis, and curation of archaeological human remains (see Roberts 2019 for summary). The British Association for Biological Anthropology and Osteoarchaeology (BABAO) released a Code of Ethics in 2010, which was updated in 2019 (BABAO 2019a). This code states that research involving human remains is "a privilege and not a right" (BABAO 2019a, 4). It advocates for consistently treating human remains with dignity and respect, recognising that current opinions regarding the study of archaeological human remains will vary between different groups of people, ensuring that human remains are only analysed for "legitimate" reasons, and balancing resource availability and preservation concerns with the new scientific information that can be gained from analysis (particularly destructive analysis) (BABAO 2019a, 5).

It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss the contents of all relevant bioarchaeological guidelines, but some signposting is helpful. BABAO's Code of Practice (written in 2010 and updated in 2019) and the Advisory Panel on the Archaeology of Burials in England's (APABE) Science and the Dead include guidelines and recommendations for the implementation of destructive analysis of human remains (APABE 2023; BABAO 2019b). There are several UK-based guidance documents which provide standards for the osteological recording of archaeological human remains (Brickley and McKinley 2004; Mitchell and Brickley 2017) and for the excavation and treatment of human remains from English Christian burial grounds (APABE 2015; 2017). The Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) issued guidance regarding the treatment, curation, and display of human remains in museum contexts (DCMS 2005) and BABAO (2023) recently released a statement staunchly opposed to the selling and trading of human remains for commercial profit.

There has been a push within the scientific world to develop a framework by which Indigenous Peoples (as creators and owners of various types of data) can "reclaim[ing] control of data, data ecosystems, data science, and data narratives in the contexts of open data and open science" (Carroll et al. 2020, 2). Although the CARE principles do not exclusively address bioarchaeological data, they can apply to all bioarchaeological analyses that involve Indigenous remains. These principles emphasise that data should be used for collective benefit, acknowledge Indigenous Peoples' authority to control such data use, highlight the responsibility of researchers to develop respectful relationships with involved Indigenous Peoples, and recognise that "minimizing harm and maximizing benefit" is essential for ethical data use (Carroll et al. 2020, 1). Relevant US-based sources specifically addressing bioarchaeology include Alfonso and Powell (2007), who provide practical guidelines for researchers, and the code of ethics from the American Association of Biological Anthropology (previously the American Association of Physical Anthropology) (AAPA 2003) and the statement of ethical principles from the Paleopathology Association (PPA 2023).

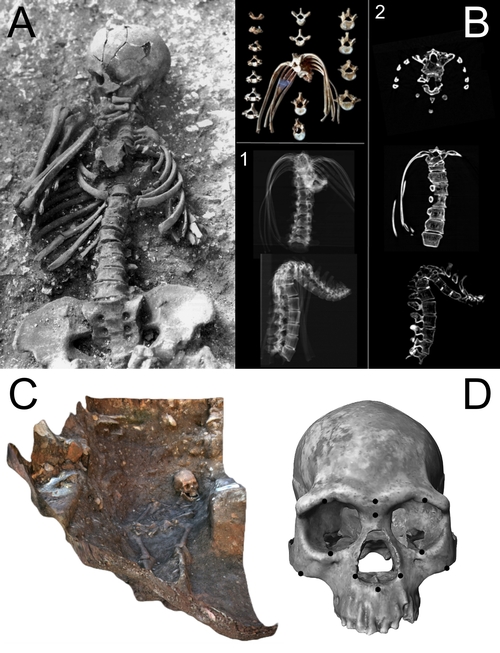

In recent years, digital technologies for the recording and analysis of human remains have become easier to use, cheaper, and more accessible, leading to increased activity within the field of digital bioarchaeology (Errickson and Thompson 2019). Digital bioarchaeological data has been described as "any data that represent human remains in a digital format", and can include spreadsheets which contain osteological data or 2D/3D visualisations of human remains (Hassett 2018, 223). The most common ways to record digital bioarchaeological data include photography, radiography, photogrammetry, laser surface scanning, structured light scanning, CT scanning, and MRI scanning (Hassett 2018; BABAO 2019c; Wrobel et al. 2019) (Figure 1).

3D models of human remains have considerable value in curation, research, teaching, and outreach contexts. Although 3D digital models or 3D printed models should not be considered replacements for physical human remains, some types of analysis are possible using digital visualisations, reducing the risk of damage by physical manipulation (Errickson et al. 2017; Hirst et al. 2018; BABAO 2019c). Virtually available 3D models can allow researchers to perform some types of work more efficiently and cost-effectively, and they are able to access archaeological individuals that might have been impossible or too expensive, difficult, or far away to access physically (Errickson et al. 2017; BABAO 2019c; Schug et al. 2021).

Access to digital 3D models of human remains can also be extremely beneficial for the academic teaching of bioarchaeology, osteology, and palaeopathology modules as instructors can refer to models that depict a specific skeletal attribute or pathology that they might not have an example of within their institution's collection (Errickson et al. 2017; BABAO 2019c; Schug et al. 2021). Similarly, digital 3D models and the derivative physical 3D printed models are valuable for outreach and engagement with the general public (Errickson et al. 2017; BABAO 2019c; Smith and Hirst 2019; Schug et al. 2021). Surveys have shown that the majority of people are supportive of the display of human remains in British museum contexts and that their inclusion in exhibits helps visitors learn about life in the past (Mills and Tranter 2010; Leeds Museums & Galleries 2018). At the British Museum, the addition of an interactive table with a 3D model of the Gebelein Man alongside the physical remains of the mummified individual improved visitors' exhibit experiences (Ynnerman et al. 2016). Because digital 3D models can be interacted with by the general public, the visitor's experience becomes more personal and exploratory, echoing the discovery process of the original researchers (Ynnerman et al. 2016).

3D recording of in situ human remains in excavation contexts has proved useful for better understanding taphonomic processes, funerary treatment, and burial sequence, associating contexts that were excavated at different times, and effectively recording in situ human burials when skeletal preservation is poor, the excavation environment is challenging, and/or there are time and cost constraints (e.g. Wilhemson and Dell'Unto 2015; Novotny 2019; Valente 2019; Villa et al. 2022). Finally, the imaging of human remains after they have been removed from the ground (CT scanning, photogrammetry, laser scanning, etc.) can help palaeopathologists with, for example, new and retrospective diagnoses (e.g. Paja et al. 2015; Coqueugniot et al. 2020), better visualisation of skeletal alterations (e.g. Buzi et al. 2020), sex assessment and age estimation (e.g. Shearer et al. 2012; Pattamapaspong et al. 2019), trauma analysis (e.g. Urbanová et al. 2017; Nogueira et al. 2019), measurement of cranial landmarks (see Kuzminsky and Gardiner 2012; Omari et al. 2021), and improvement of inter-institutional and international collaboration (Kuzminsky and Gardiner 2012).

As technology advances, recording, analysis, and interpretation of human remains increasingly utilise digital technologies and visualisations, and therefore the consideration of ethical approaches to digital bioarchaeology and the use of 3D models is necessary (Márquez-Grant and Errickson 2017; Hirst et al. 2018; Errickson and Thompson 2019; Smith and Hirst 2019; Schug et al. 2021). While there is a considerable amount of literature pertaining to the ethical and respectful excavation, treatment, analysis, and display of physical human remains (see Section 2.1), discussion of reflexive, ethical approaches to the collection, curation, and dissemination of digital human remains is relatively recent, and the development of ethical guidelines is of the utmost importance (Márquez-Grant and Errickson 2017; Hirst et al. 2018; Smith and Hirst 2019; Schug et al. 2021).

In 2016, experts from various archaeological and forensic fields met at the 8th World Archaeological Congress to discuss the growing number of ethical issues surrounding the creation and sharing of digitised human remains (Hassett et al. 2018). This meeting resulted in a short resolution which emphasised three main points: authorship should be determined and all stakeholders identified, visualisations must always be contextualised, and deciding who has access to a visualisation should be situation-dependent (Hassett et al. 2018). These basic principles continued to be fleshed out in the coming years with the publication of academic journal articles and edited volumes that discuss how digitised human remains should be created, used, and shared for teaching, research, and outreach purposes.

Schug et al. (2021) offer the most comprehensive ethical guidelines developed specifically for digital bioarchaeology. Bioarchaeological research involves overlapping fields of ethical theory including biomedical, anthropological, and scientific ethics, and these different approaches are sometimes at odds with one another (Schug et al. 2021). This means that a rigid ethical approach to digital bioarchaeology is not appropriate (Schug et al. 2021). Instead, researchers must recognise that ethical and moral responsibilities are situation-dependent, fluid, and will vary on a "case-by-case basis", and therefore they must be reflexive and ready to adapt (Hassett et al. 2018, 336; Ulguim 2018b, 217; Schug et al. 2021). When deciding if or how to create, analyse, and share a digital visualisation of human remains, Schug et al. 2021 provide 22 points of ethical consideration. The list below addresses the points that are most pertinent to this paper:

Reuse of archaeological data can be inhibited by a lack of contextual information as re-users may be unable to verify the authenticity of the original data (Faniel et al. 2013). Different data reuse projects will require varying levels of contextualisation, and therefore a lack of/poor contextualisation can be a significant obstacle in terms of archaeological data reuse (Huggett 2018), particularly in terms of digital bioarchaeology (Ulguim 2018b). This emphasis on the idea that "context is key" is a common thread that is essentially universal in literature pertaining to the ethics of digital bioarchaeology (Williams and Atkin 2015; Márquez-Grant and Errickson 2017; Ulguim 2017; Hassett et al. 2018; Hirst et al. 2018; Ulguim 2018a; 2018b; Errickson and Thompson 2019, 305; Schug et al. 2021; Alves-Cardoso and Campanacho 2022). To avoid models becoming "divorced from context" (Ulguim 2017, 83), the inclusion of metadata is essential and should include information about provenance, tracing of consent (or lack of consent) for scanning/sharing, osteological analysis, and funerary context (Ulguim 2017; 2018b; Hirst et al. 2018; Schug et al. 2021). Without this information, 3D models of human remains become decontextualised, floating entities, and the archaeological individual who was buried, excavated, analysed, and scanned becomes dehumanised and runs the risk of being perceived simply as a morbid curiosity. When archaeological funerary objects or human remains are separated from their context, the ability of those remains (be they a part of a physical exhibit, digital 3D model, vlog/blog, etc.) to "choreograph powerful, potentially disturbing and emotive engagements with human mortality in a sensitive manner" for users/visitors/viewers is compromised (Williams and Atkin 2015).

Technical contextualisation, including metadata and paradata, is also necessary (Ulguim 2018b). Ulguim (2017; 2018b) highlights the fact that although 3D models of human remains are very photorealistic, the creation of the model itself is a subjective process that relies on the expertise and decision-making of the creator. This is an issue that has been raised previously with regards to heritage-based visualisations: there always remains the possibility that users of such visualisations, who are in many cases 'non-experts', will interpret a model's photorealism as "historical truth" and remain unaware of the subjective, interpretive creation process that was required (Frankland and Earl 2011, 63; Watterson 2012). As stipulated in The London Charter (London Charter Initiative 2009), all 3D models should be accompanied by strong metadata and paradata that describe the process behind the creation of the model. This includes models depicting human remains, and by including metadata and paradata alongside these, new interpretations can be made (Ulguim 2017; 2018b). Adhering to interoperable metadata ontologies would improve the reusability of digital bioarchaeological data, and it has also been suggested that persistent unique identifiers (e.g. a DOI) should be assigned to archaeological 3D models, including those that depict human remains (Ulguim 2018b; Champion and Rahaman 2020; Fritsch 2021).

As digital recording technologies become more accessible, cheaper, and easier to use, utilising these modalities to scan and analyse human remains is becoming more common (Errickson and Thompson 2019). It is important to remember that "this form of data is the digital record of a person who had once lived, so a key consideration is to also treat this representation with as much dignity and respect as the body itself" (Márquez-Grant and Errickson 2017, 195). Although digital technologies for recording and analysing human remains are becoming increasingly accessible, justification for such recording and analysis is essential: 3D scanning performed simply because it is possible is inappropriate and disrespectful to the deceased (Márquez-Grant and Errickson 2017).

Beyond justification for scanning, permission must also be sought from descendent communities, genealogical relatives, stakeholders involved in repatriation, and any individuals or institution/s responsible for curation (Hirst et al. 2018; Schug et al. 2021). 3D scanning is often considered a solution when facing loss of access to physical human remains in cases where repatriation and/or reburial occurs. However, it is important to consider that not all communities will differentiate between the original and the replica, and therefore explicit permission must be obtained for the scanning of reburied or repatriated remains (Smith and Hirst 2019). Guidelines specifically for the scanning and curation of Indigenous ancestral human remains with regards to collaboration, respect, curation, ownership, and repatriation are provided by Spake et al. (2020).

Literature pertaining to ethical considerations within the field of digital bioarchaeology is becoming more widely available, and it is recognised that more work in this area is necessary (e.g. Márquez-Grant and Errickson 2017; Hirst et al. 2018; Smith and Hirst 2019; Schug et al. 2021). Several key considerations and suggestions that are particularly relevant to this paper are addressed in the existing literature with regards to the creation and sharing of digitised human remains:

Although academic discussion regarding theoretical ethical approaches to the dissemination of 3D bioarchaeological data is becoming more frequent (Section 2.2.2), studies that address how users prefer to be presented with this data are rare. A recent study by Alves-Cardoso and Campanacho (2022) implemented an online survey which explored the opinions of Portuguese residents (N=312) regarding the sharing of 3D models depicting human remains online. The majority of participants were supportive of the sharing of this type of data online for educational (61%) or research purposes (81%), and believed that they could be shared on museum websites (66%), university and/or research centre websites (95%), or 3D model online repositories such as Sketchfab (69%). Considerably fewer respondents supported the sharing of 3D models of human remains on news websites (15%) or social media (12%). A slight majority either somewhat disagreed with (22%) or strongly disagreed with (30%) allowing 3D models depicting human remains to be downloaded by the public for personal use, and a majority believed that registration and log-in should be required to access this type of data (64%). Finally, a large majority either strongly agreed (65%) or somewhat agreed (19%) that description/context should always be included alongside an online 3D model depicting human remains (Alves-Cardoso and Campanacho 2022).

To the author's knowledge, a similar type of survey has not been performed in the United Kingdom. The survey described in the second half of the paper is specific only to the dissemination of digital bioarchaeological data through an official repository like the ADS and does not consider social media or online news websites. As the ADS is starting to receive multiple archives that include a large volume of 3D bioarchaeological data, the results from this study can inform the ADS regarding its approach to the dissemination of this type of sensitive data.

The first part of this paper addressed why ethical considerations with regards to digital bioarchaeological data are essential as the use of this type of data continues to grow in commercial, academic, and outreach contexts. The second part of this paper will discuss how these ethical considerations are being taken into account by the ADS as it develops a protocol for the dissemination of large-scale digital bioarchaeological data.

The ADS is a CoreTrustSeal accredited digital repository for archaeological and historic environmental data that is based in the United Kingdom. It primarily receives data from UK-based archaeological excavations and projects that are developer-funded or research-based (Wright and Richards 2018). The designated user community of the ADS "is archaeological practitioners and researchers based in the UK: those working within the research and university environments, the commercial archaeological sector, history and heritage organisations, museums, secondary and tertiary education, community archaeology and heritage groups" (ADS 2024).

Digital curation organisations such as the Digital Preservation Coalition (DPC) have recently begun to place more emphasis on the ethics of digital preservation. For example, the DPC Rapid Assessment Model (RAM), which is used by companies to evaluate their "preservation capability and infrastructure", now includes a section which addresses the ethical and cultural aspects of digital preservation (DPC 2024, 2). In order to be "optimized" with regards to Organizational Capability C (the "management of legal, social and cultural rights and responsibilities"), a company must reach the targets shown below. The ADS takes part in an annual self-assessment following the standards set out in the DPC RAM. Requirements to be considered "optimized" with regards to legal, social, cultural, ethical rights and responsibilities in the DPC RAM are that:

Adhering to the DPC RAM is not an official form of accreditation for an organisation. However, it is noteworthy that these guidelines for good practice established within an IT-heavy sector directly address the ethical implications of digital preservation, including aspects that are definitively relevant to archaeology (e.g. Indigenous and community content). With this in mind, it is clear that an exploration of how to digitally preserve and disseminate bioarchaeological data (which is sensitive in nature) is both timely and useful for a digital archaeology and historic environment repository like the ADS.

With an increase in both the use of digital recording and analysis techniques and the discovery of new, large-scale archaeological cemeteries, for example, those uncovered during construction of the High Speed 2 (HS2) (e.g. HS2 2024a; 2024b; 2024c; 2024d), the ADS is increasingly becoming responsible for the curation of large volumes of digital bioarchaeological data such as photographs, 3D models, and spreadsheets. For example, photogrammetric 3D models of in situ inhumation and cremation burials from HS2 cemeteries are currently being processed by the ADS (over 2,900 from St Mary's Church, Stoke Mandeville, Buckinghamshire; over 450 from Fleet Marston, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire; c.145 from Wendover Green Tunnel, Wendover, Buckinghamshire). Therefore, an exploration as to how the ADS can appropriately disseminate this type of sensitive data is essential.

With this in mind, the remainder of this paper aims to:

The following project was developed for the dissertation component of the MSc in Digital Archaeology programme at the University of York. In order to examine how potential ADS users prefer to be presented with digital bioarchaeological data in an official repository context, an online Qualtrics survey was developed. Before the Qualtrics survey was created, ethical approval was sought and granted from the University of York's Arts and Humanities Ethics Committee. An Information Sheet was produced which introduced participants to the study, delivered a content advisory regarding the inclusion of images of human remains, explained how the collected data would be used and managed, and provided appropriate contact information. This was followed by a series of four Yes/No questions which determined a respondent's consent to participate.

The first survey question addressed the participant's experience or interest in archaeology or a related field. This was included to allow for comparison between participant responses based on their familiarity with the field. The next part of the survey consisted of ten questions organised into four 'blocks' which addressed participant familiarity with the ADS (Block 1), pop-up content advisories (Block 2), contextual information (Block 3), archive-specific ethics statements, and terms of download (Block 4). The survey questions are summarised in Table 1. All screenshots included in the survey were made by manipulating and editing a screenshot of an unpublished ADS archive page using Paint.net. Excluding Questions 1–3 and 6, optional text response boxes were included for each question to allow participants to expand upon their opinions if they wished.

After participants completed the ten questions, they were offered the optional opportunity to provide their e-mail address if they wanted to be sent a digital copy of the finished thesis or any other open access articles based on this research. Finally, there was an optional demographics section with four questions that addressed the participants' gender, age, nationality, and religion. These questions were included so that the potential for identity-based biases in terms of survey responses could be explored.

The anonymous link to the Qualtrics survey was disseminated through social media, mailing lists, and personal requests by the author. Responses were collected between 26 June 2023 and 13 July 2023. The link was shared on the author's personal Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and X (formerly Twitter) accounts. Additionally, several appropriate public/private Facebook groups were identified as having relevant audiences (both for archaeologists and non-archaeologists), and the anonymous link was posted within these (e.g. Survey Sharing - Survey Exchange/Swap - Find More Survey Participants; MENTORING Womxn in Archaeology and Heritage; Archaeology; Digital Archaeology Group; Paleopathology; Paleopathology Association Student Group). Private messenger on Facebook was also used to send the anonymous link directly to the author's connections, many of which had some knowledge of archaeology or related fields. On X, the hashtags #Archaeology, #AcademicTwitter, #osteology, and #Dissertation were used, and the ADS and University of York were tagged to increase views. The anonymous link was also shared via e-mail to BABAO's mailing list and personal WhatsApp groups, and different museum and Historic Environment Record colleagues with whom the author has previously collaborated were also contacted via e-mail.

Before analysis began, e-mail addresses and their associated respondent ID numbers were exported to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and stored on the University of York cloud storage system. At this point, e-mail addresses were deleted from the Qualtrics account to allow for analysis with a decreased likelihood of participant identification. Surveys that were less than 50% complete were removed from the dataset.

The full dataset was exported to Microsoft Excel and then transformed into a format that could be analysed in IBM SPSS Statistics v. 28.0.0.0 (190). SPSS chart builder was used to create bar charts for the count of each response option for each survey question. SPSS chart builder was also used to build stacked bar charts which displayed the responses to a certain question grouped by the way in which participants responded to a separate question. For example, a stacked bar chart was created that showed what percentage of participants who answered "Yes" to Question 6 (they would want a 3D model to be accompanied by contextual information) did or did not have archaeological experience/interest.

| Question no. | Question text | Response options | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience/interest | Which best describes you with regards to experience or interest in archaeology? | I have held a job that relates to archaeology or a similar field | 69 | 20.1 |

| I have a degree in archaeology or a related field | 58 | 16.9 | ||

| I have a degree in archaeology or a related field AND I have held a job that relates to archaeology | 146 | 42.4 | ||

| I have a general interest in archaeology or related fields | 64 | 18.6 | ||

| I have no interest in archaeology or related fields | 6 | 1.7 | ||

| I am unsure what archaeology is | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| Experience/interest question total: | 344 | 100.0 | ||

| 1 | Have you previously visited or downloaded data from the Archaeology Data Service website? | Yes | 150 | 43.6 |

| No | 171 | 49.7 | ||

| I'm not sure | 23 | 6.7 | ||

| Question 1 total: | 344 | 100.0 | ||

| 2 | Are you aware that the Archaeology Data Service has Sensitive Data guidance which covers human remains? | Yes | 109 | 31.7% |

| No | 118 | 34.3% | ||

| I have never used the Archaeology Data Service website | 117 | 34.0% | ||

| Question 2 total: | 344 | 100.0 | ||

| 3 | Are you aware that the Archaeology Data Service has Terms of Use and Access for users who download and reuse its data? | Yes | 165 | 48.0 |

| No | 54 | 15.7 | ||

| I have never used the Archaeology Data Service website | 125 | 36.3 | ||

| Question 3 total: | 344 | 100.0 | ||

| 4 | Do you think the Archaeology Data Service should provide a content advisory for archives that contain images of human skeletal remains? | Yes | 227 | 66.0 |

| No | 76 | 22.1 | ||

| I'm not sure | 41 | 11.9 | ||

| Question 4 total: | 344 | 100.0 | ||

| 5 | Please select the option which best represents your opinion regarding when you should see a pop-up content advisory informing you that you might see human skeletal remains. | I do not believe a pop-up content advisory is required prior to viewing human skeletal remains. | 74 | 21.5 |

| I believe that a pop-up content advisory is required only when I first enter the Archaeology Data Service website. | 66 | 19.2 | ||

| I believe that a pop-up content advisory is required, but only when I enter the archive-specific webpage. | 175 | 50.9 | ||

| Other, please describe below. | 21 | 6.1 | ||

| I'm not sure | 8 | 2.3 | ||

| Question 5 total: | 344 | 100.0 | ||

| 5.5 | Please select the option which best represents your opinion regarding pop-up content advisories that appear prior to viewing human skeletal remains: | I believe that a pop-up content advisory is only required at the point when I enter the archive-specific webpage. | 30 | 14.7 |

| I believe that a pop-up content advisory is only required at the point when I enter the archive Downloads section. | 44 | 21.6 | ||

| I believe that a pop-up content advisory is required at the point when I click on/view a 3D model or image that includes human skeletal remains. | 110 | 53.9 | ||

| Other, please describe below. | 15 | 7.4 | ||

| I'm not sure | 5 | 2.5 | ||

| Question 5.5 total: | 204 | 100.0 | ||

| 6 | If viewing the 3D model of an excavated human burial on the Archaeology Data Service website, would you prefer for this model to be accompanied by its specific associated contextual information including technical, locational, funerary, and osteological data? | Yes | 324 | 94.2 |

| No | 5 | 1.5 | ||

| I'm not sure | 15 | 4.4 | ||

| Question 6 total: | 344 | 100.0 | ||

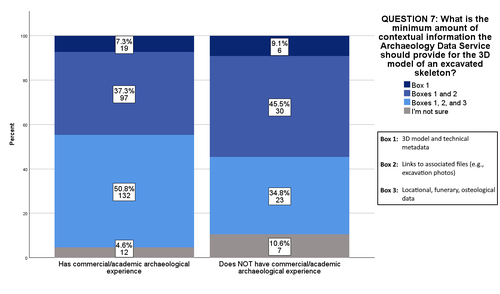

| 7 |

Creating data linkages during the production of individualised webpages for each skeleton

would potentially increase the workload of the Archaeology Data Service and would

potentially increase archival costs.

With this in mind, what is the minimum amount of contextual information the Archaeology Data Service should provide for the 3D model of an excavated skeleton? |

Box 1 | 25 | 7.6 |

| Boxes 1 and 2 | 127 | 38.8 | ||

| Boxes 1, 2, and 3 | 155 | 47.4 | ||

| I'm not sure | 20 | 6.1 | ||

| Question 7 total: | 327 | 100.0 | ||

| 8 | If increases in staff time and archival costs could be minimised, what contextual information would you prefer to view for the 3D model of an excavated skeleton on the Archaeology Data Service website? | Box 1 | 10 | 3.1 |

| Boxes 1 and 2 | 55 | 16.9 | ||

| Boxes 1, 2, and 3 | 245 | 75.2 | ||

| I'm not sure | 16 | 4.9 | ||

| Question 8 total: | 326 | 100.0 | ||

| 9 | For each archive that includes visualisations of human skeletal remains, should the Archaeology Data Service provide an archive-specific ethics statement that explains why these are included in the archive? | Yes | 164 | 50.9 |

| No | 97 | 30.1 | ||

| I'm not sure | 50 | 15.5 | ||

| Other, please explain below | 11 | 3.4 | ||

| Question 9 total: | 322 | 100.0 | ||

| 10 | When a user downloads a photograph or 3D model depicting human skeletal remains, should an extra pop-up box require them to agree to an archive-specific ethics statement? | Yes | 209 | 65.1 |

| No | 72 | 22.4 | ||

| I'm not sure | 34 | 10.6 | ||

| Other, please explain below | 6 | 1.9 | ||

| Question 10 total: | 321 | 100.0 | ||

| Gender | What gender do you identify as? | Male (including transgender men) | 71 | 22.3 |

| Female (including transgender women) | 222 | 69.6 | ||

| Non-binary/other | 20 | 6.3 | ||

| Prefer not to say | 6 | 1.9 | ||

| Gender question total: | 319 | 100.0 | ||

| Age | What is your age? | 18–24 | 43 | 13.5 |

| 25–34 | 122 | 38.2 | ||

| 35–44 | 72 | 22.6 | ||

| 45–54 | 42 | 13.2 | ||

| 55–64 | 26 | 8.2 | ||

| 65–74 | 10 | 3.1 | ||

| 75 and older | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| Prefer not to say | 3 | 0.9 | ||

| Age question total | 319 | 100.0 | ||

| Religion | What is your present religion, if any? | Buddhist | 0 | 0.0 |

| Christian | 58 | 18.5 | ||

| Hindu | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| Jewish | 4 | 1.3 | ||

| Muslim | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Sikh | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| No religion | 219 | 69.7 | ||

| Other religion, please describe | 14 | 4.5 | ||

| Prefer not to say | 18 | 5.7 | ||

| Religion question total | 314 | 100.0 |

NB: Results for the optional demographic question regarding nationality are not included in this table as there were so many response options.

A total of 453 participants started the survey. Of the 453 participants, 91 completed less than 50% of the survey and were excluded from the final dataset. Of the 453 participants, 23 did not finish the survey, but completed more than 50% and were included in the final dataset. The final dataset therefore included the survey results for all surveys that were more than 50% complete (N=344). Of these 344, 321 surveys were 100% complete. The results for the survey and optional demographics questions (excluding nationality) are provided in Table 1.

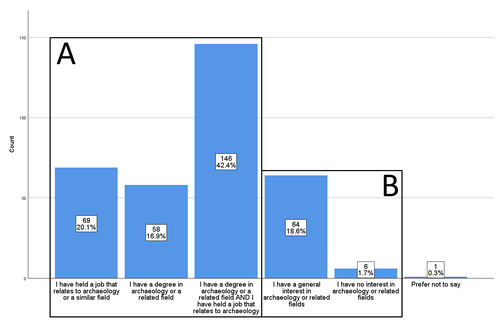

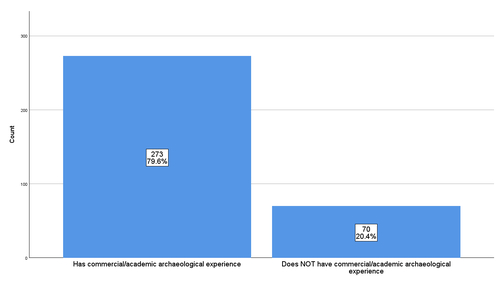

To investigate the differences in opinions between participants with commercial and/or academic archaeological experience (i.e. participants who were more likely to be part of the ADS user community) and participants without professional/academic archaeological experience, it was necessary to combine some of the response categories for the experience/interest question. The three responses in group A (Figure 2) were combined to represent participants with commercial and/or academic archaeological experience. The two responses in group B (Figure 2) were combined to represent participants who did not have professional/academic archaeological experience. The results of this data re-categorisation are shown in Figure 3.

A large majority of participants (N=273, 79.6%) had some form of academic or commercial archaeological experience (Figure 3), which makes sense given the content of the survey and where it was disseminated (see Section 3.2). Interestingly, the majority of participants identified as female (N= 222, 69.6%) (Figure 4). When considering only participants with commercial/academic archaeological experience, the percentage of individuals identifying as female was even higher (72.1%). According to the 2019–20 Profiling the Profession report, 47% of archaeologists identify as female (Aitchison et al. 2021). However, within the field of bioarchaeology, it is commonly known that the ratio of females to males is much higher. In a survey of some members of BABAO, 82% of members identified as female, while only 18% of members identified as male (Arday and Craig-Atkins 2021, 23). As the survey link was disseminated to the BABAO mailing list and was shared on several palaeopathology-related Facebook groups, it seems likely that many participants were bioarchaeologists, and therefore more likely to identify as female.

The majority of the survey participants were between the ages of 25 and 44 (N=194, 60.8%), with the largest cohort between 25 and 34 years old (N=122, 38.2%) (Figure 5). When comparing only participants with commercial/academic archaeological experience with the age categories presented in the 2019–20 Profiling the Profession report (Aitchison et al. 2021), it is clear that a younger demographic (under 35 years) was answering the survey (Table 2). This could perhaps be due to the method of survey dissemination which relied heavily on Facebook and X, which tend to be more popular among younger generations. Users between the ages of 25–34 (29.9%) and between 18–29 (42%) are the largest cohorts to use Facebook and X respectively as of 2023 (Barnhart 2023), which might explain why there were fewer older individuals participating in the survey.

| Profiling the Profession age group (years) | Profiling the profession % | Current survey age group (years) | Current survey % |

|---|---|---|---|

| >25 | 4 | >24 | 13.2 |

| 26–35 | 22 | 25–34 | 41.1 |

| 36–45 | 29 | 35–44 | 23.3 |

| 46–55 | 24 | 45–54 | 13.2 |

| 56+ | 21 | 55+ | 9.3 |

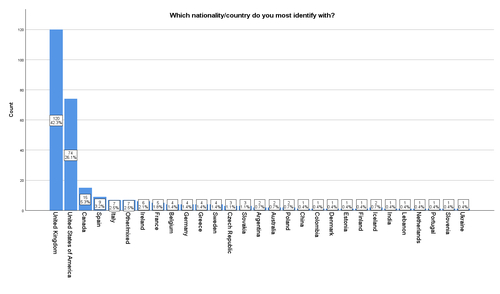

As demonstrated in Figure 6, the majority of survey participants were either from the United Kingdom or the United States (N=194, 68.4%) with the largest cohort from the United Kingdom (N=120, 42.3%). This was expected given that the ADS primarily deals with UK-based heritage and archaeological data, meaning that the survey content was more likely to be relevant to participants from the United Kingdom (either as depositors to or users of the ADS). As stated above, the survey was disseminated to the BABAO mailing list, which is UK-based, although it does have international membership (Arday and Craig-Atkins 2021, 23). A survey link was disseminated via X three times (total views= 3,832). In two of these posts, the ADS X account was tagged, and in one post the University of York X account was tagged. This may have drawn more views from UK residents as these are both UK-based organisations. Additionally, the survey link was shared on the author's personal Facebook and LinkedIn accounts, and given their personal ties to the USA and the UK, it is understandable that mostly UK or USA residents viewed and interacted with the link.

Finally, the majority of survey participants reported that they did not have any religious beliefs (N=219, 69.7%) (Figure 7). Unfortunately, there is no data regarding UK archaeologists and religious beliefs in the Profiling the Profession report (Aitchison et al. 2021), but the British Social Attitudes report from 2019 found that 52% of British citizens report that they have no religion (Curtice et al. 2019). This number is smaller among Americans (26.8% as of 2022) (PRRI 2023), who constituted 26.1% of survey participants.

Close to half of participants (N=171, 49.7%) had never used the ADS website before, while 43.6% (N=150) had (Figure 8). When only considering participants who had previously used the ADS, 82.0% (N=123) were aware of the Terms of Use and Access (ADS 2025a), while only 48.7% (N=73) were aware that the ADS's Sensitive Data guidance (ADS 2025b) addresses human remains.

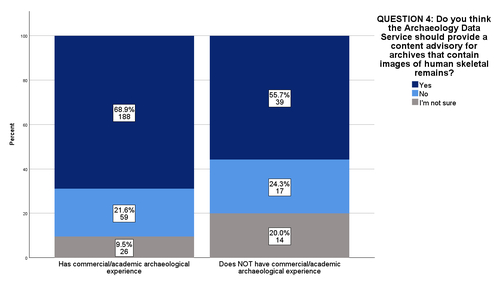

The majority of participants (N=227, 66.0%) believe that the ADS should provide content advisory for archives that contain images of human skeletal remains (Figure 9). When comparing how participants with and without commercial/academic archaeological experience responded to Question 4, it is clear that a majority of both groups believe content advisory is necessary prior to viewing human skeletal remains on the ADS website (Figure 10). However, a larger majority of participants with archaeological experience (68.9%), who are more likely to be utilising the ADS, support the inclusion of content advisory than participants without archaeological experience (55.7%) (Figure 10).

Additionally, when comparing how participants in different age groups responded to Question 4, it is clear that in all age groups except for 65–74 years and 75+ years, a majority of participants believed content advisory was necessary for archives including images of human remains (Figure 11). Although the sample size is small (N=10), it is interesting that the majority of participants aged 65–74 years did not believe content advisory was necessary (Figure 11), perhaps indicative of generational differences of opinion.

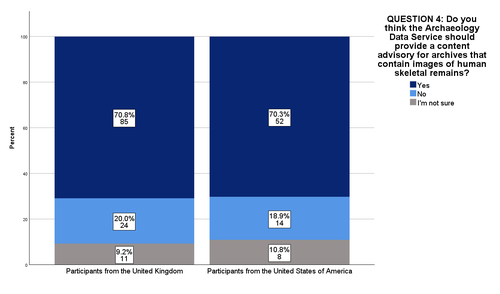

Response results were also compared between participants from the United Kingdom and the United States (Figure 12). In many previously colonised countries, including the United States, a Western, scientific approach to the analysis of archaeological individuals is not always supported by living descendants of ancestral communities (Supernant 2020). The requests and opinions of descendant communities with regards to ancestral bioarchaeological data probably feature more prominently in the work of archaeologists from the United States in comparison to those from the United Kingdom. It was therefore thought that perhaps archaeologists from the United States would be more likely than archaeologists from the United Kingdom to believe that content advisory was necessary prior to viewing digital bioarchaeological data as bioarchaeological analysis can "reopen painful wounds of generational trauma, displacement, genocide, ethnic cleansing, and loss" (Loveless and Linton 2019, 404). However, when comparing these groups, it was clear that a large majority of participants from the United States (N= 52, 70.3%) and the United Kingdom (N= 85, 70.8%) believed pop-up content advisory was necessary (Figure 12). This suggests that this opinion is very common regardless of whether the participant is from a country where considering descendant community opinions is a common part of the archaeological workflow.

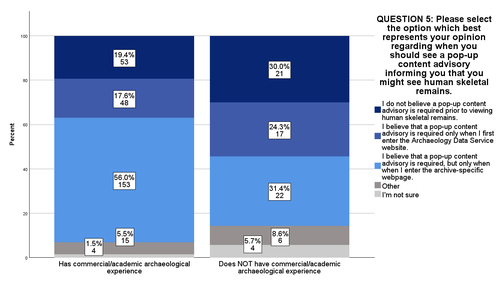

Questions 5 and 5.5 addressed where on the ADS website the user would prefer to see a content advisory prior to viewing human remains. The results from Question 5 indicate that a slight majority of users (50.9%) believe content advisory is necessary only when the user enters an archive that contains images of human remains (Figure 13). When comparing participants with and without archaeological experience, a much larger percentage of those with archaeological experience, who are more likely to be a part of the ADS's user community, preferred the content advisory to appear when entering the archive rather than any of the other options (Figure 14).

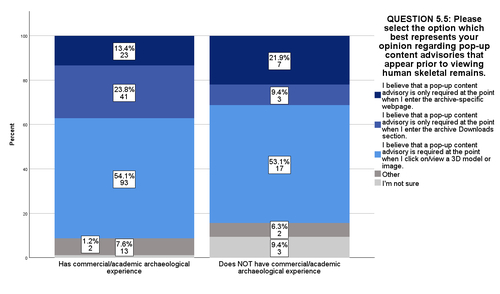

If participants answered that they did not believe content advisory was necessary or that it should appear as soon as the user entered the overall ADS website, they did not proceed to Question 5.5. Question 5.5 was designed to identify where within a specific archive the user preferred the content advisory to appear (e.g. on the Downloads page or before each different 3D model). Among participants who answered Question 5.5, those who believed content advisory should appear either upon entering a specific parent archive or when entering the Downloads section of a specific archive comprised of 36.3% of the sample (N=74) (Figure 15). A common reason for choosing these options rather than Option 3 (content advisory when clicking on each 3D model) was that having too many content advisory pop-ups would be "frustrating", "annoying", "time-consuming", and "tedious". However, it is clear that the majority of respondents (53.9%) believe that pop-up content advisory is necessary when the user clicks on or views each 2D/3D visualisation of human remains (Figure 15), which would result in a larger volume of pop-ups for the user. This majority was maintained between participants both with and without archaeological experience (Figure 16).

Questions 6–8 addressed how much contextual information participants would prefer to see alongside 3D models of human remains on the ADS website. Close to 100% of participants (94.2%) wanted technical, location, funerary, and osteological data to accompany images of human remains (Figure 17).

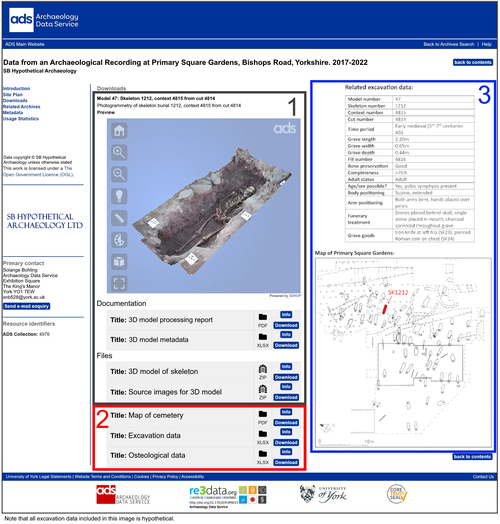

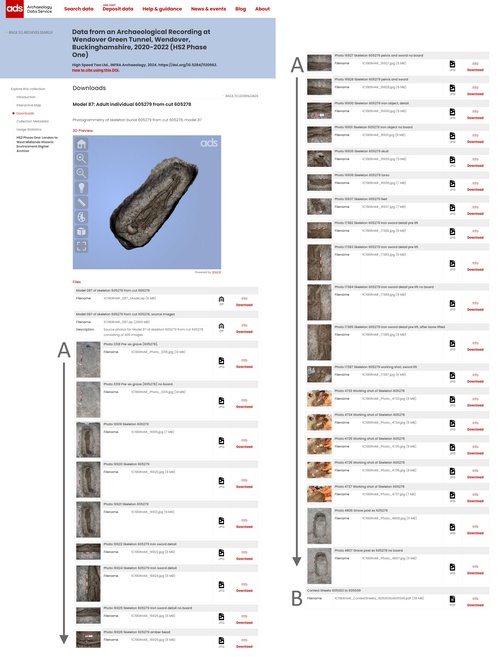

Question 7 referred to Figure E (shown in Figure 18) which presented the participants with three different boxes. Box 1 included the viewable 3D model, model files, source images, processing report, and metadata. Box 2 included links to associate data files (e.g. excavation photos). Box 3 included individual-specific information including location of the grave within the cemetery and funerary/osteological data.

The full wording of Question 7 (see Table 1) included the fact that creating data linkages during the production of individualised webpages for each 3D model would potentially increase ADS workload and archival costs. Considering this, a large majority of individuals preferred Boxes 1 and 2 or Boxes 1–3 (N=282, 86.2%), suggesting that despite the cost incurred, more contextual information was desired (Figure 19). The largest cohort of participants (N=155, 47.4%) preferred Boxes 1–3, despite knowing that providing these might increase workload and cost (Figure 19). When comparing responses of participants with and without archaeological experience, a larger percentage of those with archaeological experience (N=132, 50.8%), preferred Boxes 1–3 than those without archaeological experience (N=23, 34.8%) (Figure 20). Those with archaeological experience are more likely to have used the ADS and probably recognise the value of having further contextual information despite the additional time and financial cost.

It is also important to note that because all data on the ADS is free and open access, data re-users will not be affected by the increased cost of contextualisation, while depositors of data will. The ways in which a survey participant tended to use the ADS website were not recorded (i.e. as a re-user, a depositor, or both). However, it is important to consider how participants with commercial and/or academic archaeological experience might differ in their responses to Question 7 based on their role within the discipline (e.g. as a depositor, student, academic, museum staff) and how contextualisation might affect them financially.

The full wording of Question 8 (see Table 1), which also refers to Figure E (shown in Figure 18), hypothetically removes the risks of increased time and financial costs that are potentially associated with the provision of extra/enhanced contextual information alongside 3D models. The results of Question 8 are very clear, as a large majority (N=245, 75.2%) of respondents consider the inclusion of Boxes 1–3 to be ideal if costs could be minimised (Figure 21).

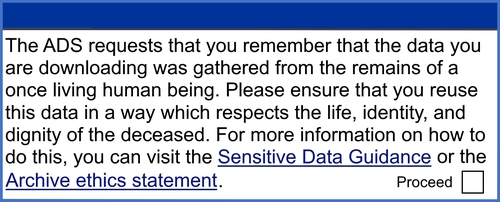

Question 9 addressed the inclusion of an archive-specific ethics statement. Although a slight majority of participants preferred an archive-specific ethics statement to be included (N=164, 50.9%), a large portion of participants did not (N=97, 30.1%) (Figure 22). Question 10 addressed whether participants believed an extra pop-up box asking users to agree to an ethics statement prior to download was necessary (example provided in Figure 24). As demonstrated in Figure 23, a clear majority of participants believed the extra pop-up box should be included (N=209, 65.1%).

The following section discusses how the results of the Qualtrics survey can be used to consider how the ADS might proceed with regards to the dissemination of digital bioarchaeological data.

Of the survey participants who had used the ADS previously (Question 1), 82.0% were aware of the Terms of Use and Access (ADS 2025a) (Question 3) while only 48.7% were aware that the Sensitive Data guidance (ADS 2025b) addresses human remains (Question 2). This means that currently, many ADS users who might download digital bioarchaeological data are not aware of the ADS's policy with regards to ethical reuse of this sensitive type of data, increasing the risk of data misuse. These results led to Suggestion 1.

Suggestion 1: The ADS should provide a clear link to the Sensitive Data guidance (ADS 2025b) in all archives that contain visualisations of human remains so that users are aware of how they should be reusing this type of sensitive data.

Of survey respondents, 66.0% believed that content advisory was necessary on the ADS website prior to users viewing human remains (Figure 9, Question 4). Upon perusal of the optional written responses to Question 4, it became clear that many participants who did not believe that content advisories were necessary thought that most ADS users would be archaeologists, and therefore would already be aware that they might encounter human remains on the website:

Other participants stated that providing a content advisory was "nonsensical" or "OTT" (over the top) (both participants have an archaeology-related degree and have held an archaeology-related job) but did not provide more detail as to why they thought this. On the other hand, many participants who believed that content advisories were necessary emphasised the fact that some people, even archaeologists, might be "uncomfortable" viewing human remains and that doing so might be "triggering". Many believed that providing a content advisory was a common "courtesy" and would "prevent harm" to any sensitive viewers:

Another common issue addressed by participants who supported the inclusion of content advisories focused on the ethical treatment of the human remains rather than the reaction of the user. Many participants believed that the addition of a content advisory would help to emphasise the special nature and importance of the once-living human behind the digital data:

"A content advisory will help people understand the severity of what they are seeing and that human remains were from a living, breathing human who deserves respect even in death." (Participant has held an archaeology-related job and is from the USA)

Although many ADS users may already be aware that they might encounter images of human remains within the repository, the majority of survey respondents advocated for the inclusion of content advisories, resulting in Suggestion 2.

Suggestion 2: The ADS should include pop-up content advisories before a user views data pertaining to human remains on their website.

The next part of the survey (Questions 5 and 5.5) addressed where a content advisory should appear prior to viewing human remains on the ADS website. A slight majority of survey respondents (50.9%) preferred the content advisory to appear when entering a specific archive that contained images of humans remains (Figure 13). Participants pointed out that having a pop-up content advisory any earlier (i.e. when you enter the overall ADS webpage) would be problematic as the advisory would be irrelevant and might prevent users from using the website:

Question 5.5 was designed to help identify where within a specific archive the content advisory should appear. The majority of respondents (53.9%) preferred the advisory to appear when the user viewed a specific 3D model rather than when entering the parent archive or the archive's Downloads page (Figure 15). However, having the content advisory appear before each model/image would result in a larger volume of pop-ups for the user. This issue was addressed directly by several respondents who suggested that after viewing the content advisory once, there should be "an I understand button which is registered once for the session". This would reduce the number of pop-ups for users who are comfortable viewing human remains without immediate warning. Based on the results from Questions 5 and 5.5, the following is suggested:

Suggestion 3: The ADS should provide a pop-up content advisory every time a user views an image or 3D model depicting human remains. For ease of use, a cookies-based 'remember this selection' option should be included to reduce the number of pop-ups during a specific browser session.

The majority of participants believed that ADS users should be required to agree to the ethical reuse of digital bioarchaeological data via an extra pop-up box prior to download (65.1%) (Figure 23, Question 10). A few participants who disagreed with this or were not sure raised the issue that the definitions of 'dignity' and 'respect' were subjective and culturally specific, and that as the pop-up box would not be legally binding, asking users to agree to reuse the data ethically would be futile:

On the other hand, many participants who answered "Yes" to Question 10 believed that this final pop-up box would serve as a reminder to users to reuse the data in an appropriate way:

Several of the participants added that while they agreed with the inclusion of the pop-up box, it should only appear "once, or once per session, or once per archive searched — not for every download". One user suggested that it would be "better to phrase the statement as a request. Something like, 'Please remember that the data you are downloading were gathered from…'". By requesting that users reuse the data appropriately, the message is not "pointless" because it has no legal repercussions, but instead reminds the user that they are dealing with data derived from once living human beings and that their reuse should respect the dignity and identity of the deceased (Figure 25). Therefore, the following is suggested:

Suggestion 3: The ADS should include a pop-up box prior to the download of digital bioarchaeological data that requests that users remember that the data they are downloading was derived from a once living human being, and that they reuse the data in a way which respects the life, identity, and dignity of the deceased. For ease of use, a 'do not remind me of this again' option should be included to reduce the number of pop-ups in a single browser session once the user has viewed the pop-up text at least once.

As mentioned above, understandings of respectful treatment of human remains can vary widely (Tarlow 2001; Curtis 2003). The ADS addresses this issue in the Sensitive Data guidance: "The inherent difficulty of fully empathising with everyone else's ideas and beliefs (in the past and the present) makes it necessary that a balanced respectful attitude is taken to the treatment of human remains" (ADS 2025b). It might be helpful to include a more detailed explanation of how the ADS interprets respectful attitudes towards human remains so that users who view a pop-up box, such as the one demonstrated Figure 25, can have a specific framework on which to base their reuse behaviour.

The role of the ADS is to provide open access to digital archaeological data, and users who download and reuse this data are agreeing to the terms and conditions provided. The ADS does its best to encourage good deposition and reuse practice, but ultimately it is not possible for the ADS to solve all cases of data misuse. It is the opinion of the author that the terms of download pop-up could inspire respectful reuse of digital bioarchaeological data by reminding users about the sensitive nature of the data and encouraging them to consider why they are downloading the data.

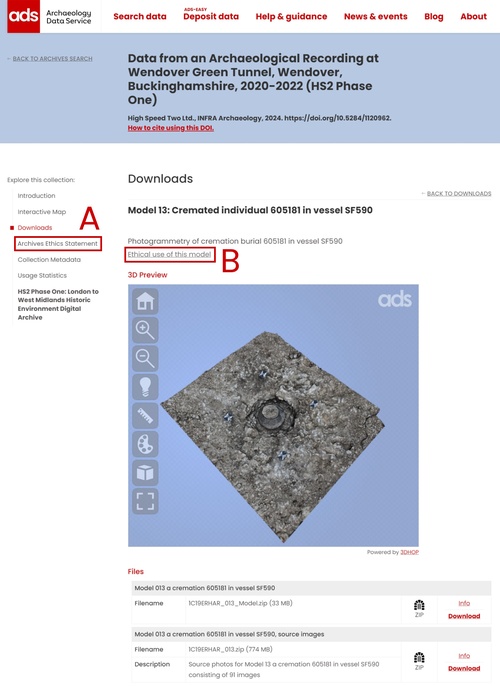

A slight majority of survey respondents (50.9%) supported the inclusion of an archive-specific ethics statement for each archive that includes images of human remains (Figure 22, Question 9). Many participants who were either not sure or did not believe an archive-specific ethics statement was necessary explained how they believed a site-wide ADS ethics statement that specifically addresses human remains would be sufficient:

Some participants thought that archives including human remains would not be different enough to merit different ethics statements, a point which is discussed in more detail below:

Several participants also pointed out that a direct link to the ethics statement should be included in each archive:

This final point links well with Suggestion 1 (Section 5.1) which calls for improving ADS user awareness of the Sensitive Data guidance (ADS 2025b) by providing a direct link within relevant archives. Removing the need for the user to search for instructions on how to reuse the data (as suggested by the above participant) might decrease the risk of data misuse. Many of the participants who supported the inclusion of an archive-specific ethics statement advocated for the inclusion of an ethics statement to ensure respectful reuse of the data:

Although some participants questioned the need for archive-specific ethics statements, a few respondents mentioned that archives might need variable ethics statements based on the nature of the human remains involved:

For example, some post-medieval cemetery excavations within the UK sometimes include identified individuals (e.g. Gabbatiss 2019), and it is possible that images or models of these individuals might be included in the deposited archive. Tracking the consent process, or the inability to gain explicit consent, helps to better understand the background of displayed humans remains (Perry 2011) and images or models depicting human remains (Ulguim 2018b). Therefore, for cases where the ADS disseminates an archive that contains information about known individuals, an archive-specific ethics statement could include the fact that permission to include these individuals was sought from living relatives or an explanation that some individuals were excluded from the archive based on the wishes of living relatives. On the other hand, many excavation archives deposited with the ADS will come from earlier periods (e.g. Iron Age, Roman) and are very unlikely to include identifiable individuals. Ethics statements for these types of archives would differ from those required for post-medieval cemeteries, but still might include an indication of awareness that consent could not be sought along with an explanation as to how the knowledge gained from analysing these individuals helps to improve knowledge of the past. Based on the results from Question 9 and the various ethical issues raised in Section 2.2.2, the following is suggested:

Suggestion 4: The ADS should provide archive-specific ethics statements (rather than a site-wide ethics statement) for archives that include human remains. This archive-specific ethics statement should be easy to navigate to within the specific archive (e.g. Figure 26).

It has been argued that standardised, unchanging ethical codes regarding the use of human remains can be "counter-productive" as they do not account for the situation-dependency of the many ethical dilemmas surrounding the analysis and display of humans remains (Tarlow 2001, 245). By including archive-specific (rather than site-wide) ethics statements, the ADS would provide valuable room for "thought, debate and discussion, rather than application of a rule" that is essential for a critical and reflexive approach to the ethical reuse of digital bioarchaeological data (Tarlow 2001, 245).

To streamline the process of creating archive-specific ethics statements, a series of templates could be developed that could be reused for different types of archives. Different sections of the templates could be completed by the depositor as they will have the best knowledge of the relevant processes (e.g. who was contacted with regards to confirming permission/consent to share, who was involved in the technical creation of the models). Márquez-Grant and Errickson (2017) and Spake et al. (2020) compiled lists of questions that should be answered for projects that deal with digital bioarchaeological data. In line with these questions and considering issues addressed by other experts in the field, each ADS ethics statement should include sections that include:

By specifically addressing common concerns identified by experts within archive-specific ethics statements, the ADS would help to set a good practice precedent for what information should be included alongside 3D models depicting human remains. It should be noted here that it is unlikely that the ADS will disseminate digital bioarchaeological data pertaining to non-UK Indigenous archaeological populations, however it remains a possibility as there are currently non-UK human remains held in museums and universities throughout the country (Section 2.1).

A very large majority of survey respondents (94.2%) preferred a 3D model depicting human remains to be accompanied by technical, location, funerary, and osteological data (Question 6, Figure 17). Question 7 asked participants how much contextual information they would prefer even if it there was a potential time and financial cost increase (see Figure 18; Box 1 included the 3D model and technical metadata; Box 2 added links to associated data files such as excavation photographs; Box 3 included further individual-specific information such as osteological data). Although it was not a majority, the largest cohort of respondents (47.4%) indicated that they preferred Boxes 1–3 (Figure 19). Several participants who answered "Boxes 1 and 2" remarked that Box 3 was helpful, but possibly unnecessary if it required too much time/financial cost as the information in Box 3 was technically available in Box 2 if the user performed independent searching (e.g. they searched the osteological spreadsheet for information about a specific individual):

On the other hand, many participants who answered "Boxes 1–3" argued that more information allows for better contextualisation which helps to "humanize the remains and respect the deceased and their culture" and "prevent assumptions that would otherwise arise without this data".

When the potential for increased time and financial costs could be hypothetically minimised, a large majority of respondents (75.2%) preferred all three boxes to be included (Figure 21, Question 8). Based on the results from Questions 6–8, it is clear that potential ADS users prefer more contextualisation alongside 3D models of human remains, which is consistent with results from Alves-Cardoso and Campanacho (2022) (Section 2.2.3). Many experts in the field of digital bioarchaeology emphasise the importance of sharing 3D models of human remains in their appropriate context (Williams and Atkin 2015; Márquez-Grant and Errickson 2017; Ulguim 2017; Hassett et al. 2018; Hirst et al. 2018; Ulguim 2018a; 2018b; Errickson and Thompson 2019; Schug et al. 2021). By including all pertinent data associated with an image or model of an archaeological individual, the "contextual data can be seen as a pathway to 're-humanise' data through storytelling" (Ulguim 2018b, 199). If the ADS can provide this contextual data that tells as much of the story of the individual as is available, users might better appreciate the life and identity of the deceased, and data misuse may be less likely. Based on the results of Block 3, the following is suggested:

Suggestion 5: If it can be made manageable with regards to cost and time, the ADS should provide as much contextual information as is available alongside each 3D model of human remains. This might include links to excavation photographs, drawings, context sheets, a searchable map interface for grave location, and post-excavation osteological analysis if/when it is provided. However, see Section 5.5.4 for a discussion of potential complications to implementation of Suggestion 5.

It should be noted here that although the survey questions and Suggestion 5 specifically address 3D models that depict human remains, a lack of contextualisation is an issue that must also be addressed with other types of historical/archaeological 3D models. Lloyd (2016) found that the majority of survey participants considered annotations useful and understood that historical context was important when they interacted with a 3D annotated model of the granite head of Amenemhat III using Sketchfab (British Museum 2014) which is physically curated at the British Museum. Similarly, Cardozo and Papadopoulos (2021) concluded that "providing compelling and effective contextualisation" was essential for survey participants to appreciate the aura and authenticity of 3D models of archaeological objects using the Rosetta stone via Sketchfab (British Museum 2017) and the Lewis chess pieces via the National Museums Scotland's website (NMS n.d.).

As such, the ADS should continue to place importance on the provision of contextual information for increasing numbers of deposited 3D models and employ enhanced contextualisation processes, when possible, to improve the reuse value of these models. Keeping in mind the time and financial constraints of the project and in collaboration with the ADS, it was decided that the author would focus on the provision of enhanced contextual information for a cemetery excavation archive that contained a large number of 3D models of human skeletal remains. This would address the majority user preference and would serve as a case study for how the ADS's archiving process for large cemeteries might be altered to improve the contextualisation of excavated individuals.

The archive that was enhanced was from Wendover Green Tunnel (WGT), Wendover, Buckinghamshire, which was excavated between 2020 and 2021 by Infra Archaeology. The WGT excavation was part of the HS2 Phase 1 project, which aims to better connect London and the Midlands by rail (Stafford 2022). The excavated area produced remains from the Neolithic to post-medieval periods, but Iron Age and early medieval features were most frequent (Stafford 2022). Of primary importance to the project was the 5th–6th century early medieval cemetery which contained around 140 individuals, a majority of whom were inhumed rather than cremated (Stafford 2022).

Infra Archaeology deposited the excavation archive with the ADS. The archive includes several main types of data:

An individual skeleton contains links to almost all of these data types. For example, Skeleton 605279 and/or their grave cut was:

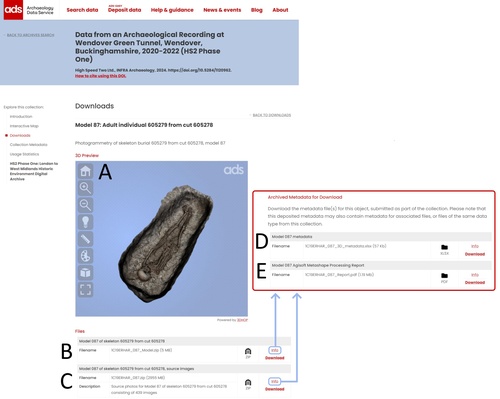

As part of ADS standard procedure, all this data would be available for download. For each of the 145 3D models, the ADS protocol would include a browser-based viewable 3D model (Figure 27, A), zipped versions of the 3D model files (Figure 27, B) and source images (Figure 27, C), the metadata for the model (Figure 27, D), and the processing report for creation of the model (Figure 27, E). A user wishing to find the skeleton's location within the cemetery, associated context sheets, excavation photographs, or osteological data would therefore need to do a considerable amount of perusing of the data to locate the information they needed.

When Infra Archaeology deposited the archive with ADS, linkages between an excavated individual/3D model and its other forms of associated contextual data (e.g. original context form, excavation photographs, drawings) were not easy to identify, and it was necessary to create these linkages manually. This process included:

Each of these files was associated with the correct skeletal model as demonstrated in Figure 28 which shows the current individualised webpage for Model 87 (Individual 605279). The associated excavation photographs are now included beneath the model files and source images and a link to the relevant context sheet PDF file is also provided. The context sheet can be referred to by users for specific information recorded by the excavator, and the photographs demonstrate what the excavator found important (e.g. working shot of the sword lift) and can be used to better understand the in situ burial.

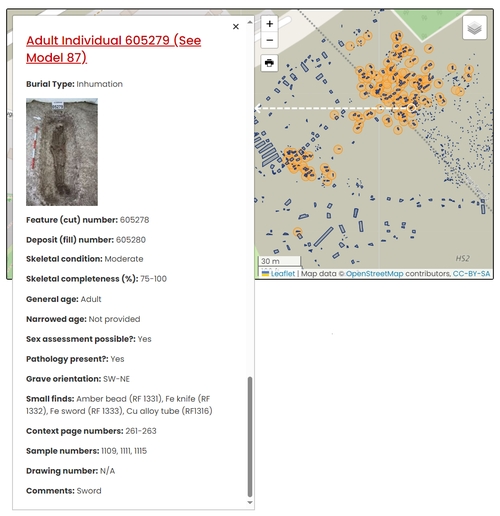

Based on the survey results, which suggested that users preferred individualised webpages for archaeological individuals (Section 4.4 and Section 5.5), the ADS developed an interactive map interface that provides grave location, specific information about the excavated individual, and a link to the model page. This process involved:

From this information, a spreadsheet was created which included each skeleton number and its associated context, grave fill, and model numbers, polygon spatial coordinates, and post excavation information (e.g. small finds, grave orientation, preservation, completeness, adult status, presence of pathology, and samples taken). This spreadsheet was uploaded to the ADS Special Collections database, creating a map which identified the location of each excavated individual within the cemetery. The user can click on the point associated with each skeleton and the associated contextual information appears as a pop-up (Figure 29). On a separate tab, there is also a list of each excavated individual and a link to their associated 3D model. This format allows users to place each excavated individual in their appropriate context, drawing on all sources of data provided by Infra Archaeology.

As demonstrated in Sections 5.5.1–5.5.3, the process to more comprehensively contextualise a cemetery archive that includes many images or 3D models depicting human remains is complex and requires a considerable amount of time to complete. Therefore, Suggestion 5 could be difficult to implement. Suggestion 5 places increased responsibility on the ADS to ensure that "enough" contextual information is provided alongside images/3D models depicting human remains. What constitutes "enough" is subjective, although it is anticipated that most commercial archaeology companies will deposit excavation context sheets for each burial which can be used to pull out specific information about each individual, as seen with the WGT archive. While it is expected to be rare, it is possible that a depositor might only provide photographs of excavated individuals or a standalone spreadsheet with osteological data. In these instances, the author argues that if no further information or data is deposited to provide at least general background contextual information about the skeletons in question, the ADS should return the archive and request further contextual information.

While it is certainly positive that so many potential ADS users prefer more contextual information alongside images/3D models depicting human remains and identify that the maximum amount of contextual information is more respectful and allows for more informed data reuse, ensuring that the contextualisation process is "manageable" with regards to time and financial cost is complicated. Since completion of the research described in this paper, which was performed as an MSc placement student, the author has been employed by the ADS's sister organisation, the Heritage Science Data Service (HSDS), as a Digital Archives Assistant and has performed similar contextualisation processes for two further HS2 cemeteries. The archives deposited with the ADS for the cemeteries at St. Mary's Church, Stoke Mandeville, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire and Fleet Marston, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire include over 2,900 and 450 3D models respectively. Given the magnitude of performing manual linkages for such a large number of individuals, the contextualisation procedures that were adopted were scaled back when appropriate and were archive-specific.

The time and cost required to complete the archival process to the same standard for such collections is higher than average, partially because of the format and organisation of the bioarchaeological data deposited. Bioarchaeological data is personal: it concerns the past lives of once living human beings. Based on the results of the Qualtrics survey, potential ADS users recognise this and prefer that such data be highly contextualised. As such, the time, effort, and cost to disseminate a bioarchaeological archive that is contextualised to this standard must be passed on to the developers.

The author suggests that commercial archaeology companies planning bids to excavate large cemeteries should factor more time and budget for data management into their proposals to developers so that they can deposit the data with ADS in a format that allows for easier and more efficient contextualisation of human remains. Further, data depositors and the developers financing their projects should consider how a more individualised, contextualised, and custom dissemination of their cemetery archives with the ADS will help users appreciate the sensitivity and uniqueness of the bioarchaeological data. Even if this means the developer must budget more time for post-excavation data management, approaching dissemination of cemetery archives in this way will:

And, perhaps most importantly, a well-contextualised cemetery archive will help to humanise the skeletons behind the data, encouraging more ethical, informed, and respectful re-use.

As the ADS is increasingly becoming responsible for the curation of large volumes of digital bioarchaeological data, an investigation into how an official, UK-based, online repository can disseminate this sensitive type of data in an informed manner was valuable. The results from this paper help form a solid, data-driven basis which the ADS can reference as it establishes its future protocol for the dissemination of digital bioarchaeological data.

Using an online Qualtrics survey, this research has explored how potential ADS users prefer to be presented with digital bioarchaeological data in an official repository context. The results of the Qualtrics survey were analysed to develop a series of suggestions that can inform the ADS regarding its dissemination process for bioarchaeological data. It is suggested that the ADS:

Complications with this final suggestion include increased time and financial cost (Sections 5.5.2 and 5.5.3) which should be passed on to the developer. By budgeting for increased time and staff for post-excavation management, depositors can provide the ADS with bioarchaeological data in a format that is conducive to efficient contextualisation, allowing their archives to be disseminated in an individualised way that appreciates the uniqueness and value of bioarchaeological data.