Cite this as: Belford, P. 2025 Time, Space and People: Urban Archaeology and Urban Futures, Internet Archaeology 70. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.70.2

Archaeology can offer important insights into both the historical trajectory of urban places and the potential futures they may create. Modern towns and cities are simultaneously places of habitation and archives of human experience. The speakers at the 2024 European Archaeological Council/Europae Archaeologiae Consilium (EAC) heritage management symposium, many of whom have also contributed to this volume, explored several aspects of the curation of these living urban archives. There were three key themes at the heart of the meeting: defining significance; managing research frameworks; and the practice of urban archaeology. One of the great delights of the process of heritage management, which is reflected strongly in both the symposium and this volume, is the way in which these themes are discussed and developed in different ways by different colleagues, each drawing on their own particular personal and cultural experiences.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the understanding and articulation of cultural heritage significance. Several speakers at the symposium, including Thor Hjatalin, Dan Miles, Inge van der Jagt and Barney Sloane, reminded us that not all cultural heritage is equally valuable. Indeed, very similar cultural heritage may embody different values in different places and at different times. These values give rise to the notion of significance, but this too varies enormously between people and communities; moreover, the structures and frameworks that we have developed to try and articulate those variations can be simultaneously inclusive and exclusive. Research frameworks are intended to help heritage managers prioritise, but can sometimes act as constraints; guidance needs to be balanced with freedom to innovate and improvise.

Understanding the past can help us design urban spaces that are more inclusive, sustainable and meaningful (and indeed joyful) for future generations. But how do we achieve this? How can urban archaeology best inform our understanding of historical transitions, spatial networks and interactions between people and their urban environments? How will urban archaeology realise its potential to enhance the development of future cities? How might we, as archaeologists and heritage managers, create systems, frameworks and processes that facilitate flexible engagement with cultural heritage in present-day urban settings, and engage modern populations in coordinated and coherent ways? This chapter offers a personal reflection on the symposium through three different lenses of enquiry and practice: time, space and people.

One of the most persistent challenges for archaeologists is enabling non-archaeologists to understand how we perceive time. The archaeological brain fluctuates between micro and macro temporal scales; our relative chronologies might sometimes be tied to absolute dates, but quite often they float freely in their own spectrum, which is outside the linear date-based structure of historical progression that most people use when they think about the past, if they think about it at all. This creates a point of critical tension in urban archaeology, as Per Cornell pointed out in his keynote at the symposium. Of course, it can be very helpful for archaeologists to construct narratives around familiar anchor points in public consciousness. Doing so helps facilitate the creation of research networks, makes it easier to frame funding applications, and provides accessible routes for promoting public awareness and understanding. This approach also has value in a heritage management context, where the significance of the archaeological resource can be clearly articulated to spatial planners and engineers, who can then manage their work to mitigate heritage impact, for example as in Prague and Riga (Novák et al. 2025; Zirne and Lūsēna 2025). Similarly, the complex Roman remains in the suburbs of Bregenz also clearly embody value that relates to a familiar historical theme, and so significance can be clearly articulated to non-archaeologists (Picker 2025).

However, the downside of this approach is that it tends to reinforce existing narratives that are structured around conventional anchor points. This runs the risk of marginalising transitional phases: and these transitions can be critical to understanding the broader evolution of cities. Of course, to undertake urban archaeology is to conduct a stratigraphic exercise, and in any excavation there will certainly be a difference between (say) Roman layers at the bottom and 16th-century layers at the top. However, only on very rare occasions does a hard line exist between one era and another. To paraphrase Indiana Jones, 'X' almost never marks the spot, except in the case of well-documented conflagrations or other catastrophes that leave a characteristic stratigraphic signature. Usually, medieval horizons become modern horizons only gradually and not always coherently. The distinction between one layer and the next is subtle; it may only be evident through slight changes in material culture, which only become apparent much later in the archaeological process. The point where one period stops and another begins is a fuzzy boundary that may represent several generations, or even several centuries.

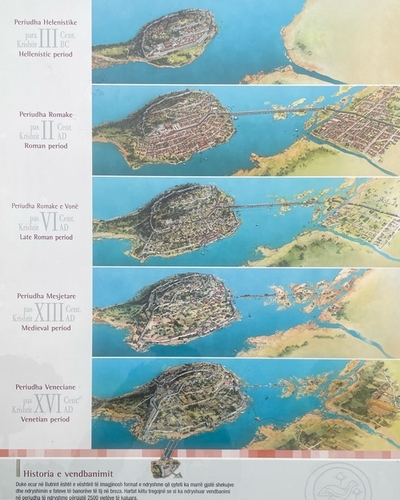

The consequence of this historiographic prioritisation is that the archaeological record tends to privilege well-documented and extensively studied periods. Roman and 'high medieval' remains, or, as we see in the case of Antwerp, post-medieval fortifications, often dominate public discourse about European urban development (Carver 1997; Martens et al. 2020). Their survival also disproportionately impacts thinking about regeneration, and the way in which heritage can influence the creation of modern urban landscapes. Monumental or otherwise robust remains are easier to excavate, conserve and interpret. They are tangible touchstones of history, helping to construct narratives of urban continuity and status (Figure 1). This sort of affiliation is a two-edged sword. For example, the 1989 discovery of the Rose Theatre in London was presented in a way that emphasised its association with Shakespeare, generating wide public recognition of its archaeological significance, which ultimately sparked the adoption of 'polluter pays' principles in UK archaeology. However, subsequent archaeological work on London theatres has remained framed by late 16th-century Shakespearean associations, rather than exploring other themes and periods (Bowsher 2012; Single and Davis 2021).

Such emphases can lead to an oversimplified understanding and presentation of urban development, leading to the creation of 'grand narratives' that give 'a dominant impression of the past as a linear and homogenous development' (Christopherson 2022). The reality is more nuanced: transitional phases are characterised by complex cultural, economic and social changes; however, because they fall outside the conventional historical narrative, even archaeologists fall into the trap of defining them as non-periods. Labels like 'post-Roman', 'early medieval' and 'post-medieval' are well-used examples of these sorts of identifiers; there are also local versions relating to particular human or natural events. The result is the proliferation of non-periods, the gaps between the major milestones of linear historical narrative, and these tend to be overlooked both in heritage management practice and in public interpretation (White 2022). However, while archaeological evidence from these hyphenated non-periods may be less dramatic, it is no less important in enabling us to understand trajectories in the living entities that are European towns and cities.

These transitions often occur where the most significant changes in urban form, society and governance take place, and so they potentially offer insights into how societies adapt to shifts in political power, economic restructuring and environmental change (Pittaluga 2020; Smith 2023; Roberts et al. 2024). Unfortunately archaeological activity, including our understanding of significance, remains somewhat imprisoned by these resilient temporal structures. Many research frameworks are ordered by conventional periods and themes, and so run the risk of overlooking developments that fall between those boundaries. New research frameworks should seek to reflect these ambiguities, to try and better capture the fluidity of urban transitions by embracing the ambiguity inherent in urban evolution (Adler-Wölfl and Skomorowski 2025). A more nuanced approach could explore dichotomies and oppositions: continuity/discontinuity, stasis/rupture, growth/decline, public/private, and so-on. This can draw on a wide evidence base, including environmental archaeology, geophysical survey and geospatial data management and interpretation, as highlighted at the symposium by Yannick Devos, Paul Flintoft, Joep Orbons and others (Devos et al. 2025; Gaffney et al. 2025).

It is also the case that urban places are simultaneously both archaeological and systemic contexts that coexist and interact (Bohn 2022). Therefore, urban archaeology only operates within the systemic framework of the modern town or city. Archaeological thinking about cities has begun to move away from traditional approaches rooted in sociological and functional explanations; instead becoming more concerned with urbanism as a series of more abstract dynamic processes and networks (Roberts et al. 2024). Urban places consist of relationships between people and places, and the constant renewal of those relationships, a process that has been characterised as 'energised crowding', is what drives the generation and regeneration of towns and cities (Smith 2023). This brings us to the question of space.

Urban places comprise many layers of highly structured spaces. Some of these are physical, such as streets, squares and buildings, and some are conceptual, such as spatial planning zones and administrative boundaries. Archaeologists use material evidence for the physical structuration of space in the past to try and understand how earlier societies created conceptual space; and we use conceptual space in the present to manage the conservation of those material remains for the future. At a narrower scale, both physical and conceptual spatial structures are quite well-defined. For example, a person is either on a street or not on a street, or a site is within a planning zone or outside it. However, at a wider scale the boundaries between these structures are rather more hazy, and many of these interfaces exist on a continuum (Simon and Adam-Bradford 2016). Moreover, cities are defined not only by what occupies space but also by what does not: those seemingly 'empty' spaces that serve as connective tissue within urban environments. These are transitional spaces, where unregulated and unconventional activities take place, both now and in the past. These liminal or marginal places can host several different types of urban practice: spontaneous appropriation, subversiveness, empowerment and flexibility (Pittaluga 2020).

This ambiguity is reflected in the practical understanding derived from archaeological practice. Many places that are urban today were not so in the past; conversely places with urban characteristics serving urban functions in the past did not survive beyond very specific sets of political, economic and cultural circumstances (Hodges 2022). In other words, urban space in the archaeological record is often 'fuzzy': boundaries between periods, cultures and uses of space are rarely clear-cut. In contrast, modern urban planning relies on precise boundaries, whether they are zoning laws, property lines or infrastructure maps. This creates a tension between the fluidity of archaeological interpretation on the one hand, and the rigid spatial demands of urban development on the other. There are therefore two aspects of space to consider. First is the tension between what we might call 'archaeological space' and the real world. Second is the nature of urban space itself, and how its significance is, or is not, considered in the day-to-day practice of heritage management.

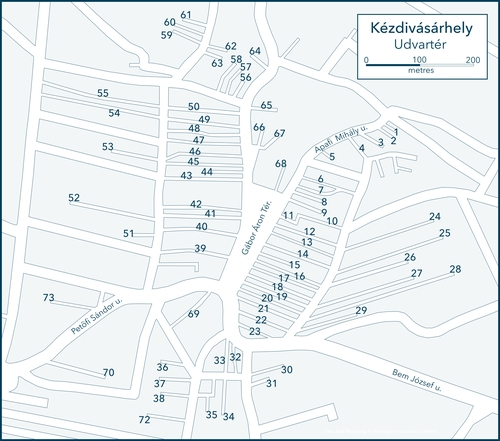

Spatial planning and other modern urban functions require 'hard' boundaries. Geospatial data is managed through a series of polygons, which have edges. Things are either inside these areas or outside them. These polygons have often been created at different times for different reasons, and so they frequently overlap and may even contradict each other. Even 'heritage' polygons are not always consistent (Figure 2). Areas of archaeological significance may not align with protection zones for historic buildings and streetscapes. In some cases there is no intellectual reason why they should: the archaeological remains may belong to entirely different periods and landscapes to those above ground (Bouwmeester 2025). However, in some places this discontinuity is a result of the present-day structures within which heritage management takes place. In the UK, for example, the conservation of the above-ground built environment and the management of the below-ground archaeological environment are the responsibility of two different groups of professionals, each with their own set of guidelines and standards, and usually operating in separate parts of local (municipal) or national regulatory authorities.

These hard boundaries make it easier for heritage managers to make decisions about significance within a legal or quasi-legal framework. But of course, the boundaries themselves can be quite arbitrary, as they rely on the historical record of archaeological intervention, which is itself serendipitous and inconsistent. Therefore, these boundaries of archaeological significance are often a best fit between the known and the unknown, or the suspected and the unlikely. Archaeological understanding results from the very intense observation of quite small spaces: a high-definition micro-spatial approach that can be very valuable in academic terms, particularly in comparative studies of population dynamics (Christopherson 2022; Jakobsen et al. 2021). However, cities are complex, layered entities. Evidence from the past does not neatly fit within modern property lines or planning zones. A Roman road may extend beneath several modern buildings; a medieval marketplace may be cut off by contemporary infrastructure; or a modern square may obscure dense medieval occupation (Bryant and Dupuis 2025; Lassau 2025; Picker 2025). It is therefore difficult to define clear boundaries of historical or cultural significance, which can create significant challenges for decision-making in an urban spatial planning context.

This brings us to the second aspect of space, which is the significance of empty spaces. As we have already seen, urban places comprise dynamic networks of connections between places, and those connections are central to the creation and evolution of urban life and identities. Therefore, these empty spaces, seemingly 'non-places', are vital to understanding how urban places function as networks (Jervis et al. 2021). However, it is much easier for archaeologists to deal with the physicality of buildings, roads, ditches, pits and other tangible elements; it is also much more straightforward to ascribe significant to these elements of the urban fabric than to less tangible spaces (Howell 2000; Giles 2007). Space is the absence of these things and so becomes more challenging to deal with both academically and managerially. Even well-defined spaces, burgage plots, lanes, squares and so-on, extend beyond individual projects, which make them harder to consider; nevertheless, with careful project design and management, extensive and detailed archaeological evidence can be recovered for their creation, modification and use (Tys 2020). Open spaces, whether public, private or somewhere in between, were (and remain) places of dynamic subversion and creativity that are central to urban development (Figure 3). Understanding the role of these empty spaces in the past can help contemporary planners design cities that foster social interaction and community cohesion.

However, understanding networks is about more than simply recognising the different and changing uses of particular spaces. Using a network approach to urban evolution can interrogate the role of connectivity in creating and inspiring changes and continuities. Networks are multi-scalar: ranging from interactions between communities in urban neighbourhoods, to landscape-scale interactions between centres and their hinterlands (Raja and Sindbæk 2021). These networks are reflected in the archaeological record through material culture; the archaeologists' role is to interrogate this record to ask questions about the human actors who created the networks. How long did these networks last? How effective were they? What was the extent to which individuals or social groups had agency within them? This brings us to the subject of people.

The consideration of time and space is not an esoteric philosophical concern, but an issue that has a direct bearing on the challenges of inter-disciplinary working and public engagement. It is quite easy for heritage professionals, and archaeologists in particular, to delve very deeply into questions of typology, matters of form, fabric and function, and other highly specialised considerations. Of course, the raison d'être for many archaeologists is to become highly absorbed in abstract specialist interests: a particular type of building, or a certain assemblage of pottery, or the micromorphology of a specific soil horizon. However, when we do so, we must remember that these are simply the material manifestations of human endeavour. At the end of the day our work is about people. People in the past but also, more importantly, people in the present and future.

This chapter has already touched briefly on the fragmentation of heritage professions when discussing time and space. It is worth expanding on this, as it impacts our ability to communicate with others outside our various bubbles. There can be significant divides between what we might loosely call 'academic' and 'managerial' approaches to heritage, and in particular to notions of value and significance. On the one hand, academic archaeologists tend to work within highly specialised and theoretically driven frameworks, using relatively small datasets to make wider inferences with reference to other academic studies. The results may provide valuable 'big picture' insights about the past, but are not always accessible or helpful for managing the present. On the other hand, commercial archaeologists tend to work in diverse multidisciplinary professional contexts where work is driven by pragmatic legal, political and financial processes. They often generate and make use of massive datasets, but their focus is on assessing and mitigating damage to individual archaeological sites in the present. Their results may provide valuable detailed information about a particular location in space (and time), but resources for synthesising wider regional or period data are usually extremely limited. Heritage managers work to reconcile these tensions between academic and commercial mindsets to achieve the delivery of projects and services; however, our primary duty is to balance conservation and urban development in the present. Therefore, our focus must be on preservation (both in situ and by record) and public understanding of cultural heritage.

These three approaches are not in opposition, but they have different goals and operate in different sectors of society and the economy. Regardless of whether we are using a model of state-led procurement (like France) or a model of private-sector delivery (like the UK), all of our work, whether academic or pragmatic in origin, is paid for by the public, and is therefore in the service of the public (Bryant and Dupius 2025; Lassau 2025; Malliaris 2025; Seppänen 2025). However, there are gaps between how we as heritage professionals understand and present our work, and how the public perceives the issues with which we are grappling. To some extent our communication issues are internal, because as archaeologists and heritage managers we understand the concept of 'significance' in specific ways. Our use of jargon, specialised terminology like 'significance', 'heritage assets', or even 'heritage management', may be helpful to us, but may not resonate with the broader public. This disconnect can make it difficult to convey the importance of urban archaeology in the broader context of redevelopment, regeneration and plan-making (Ortman et al. 2020). And we need public support to help us do our best to understand and protect the urban archaeological resource (Figure 4).

Engaging the public in meaningful ways is critical. Urban archaeology has the potential to connect the people of the past with the people of the present in interesting, inclusive and thought-provoking ways. Conventional modes of public outreach, including various combinations of community excavations and educational programmes, interpretation embodied in modern landscaping, and preservation in situ, all serve to increase public engagement (Dubisch 2025; Seppänen 2025; Zirne and Lūsēna 2025). However these sorts of approaches tend to be 'top down' on at least some level; they present the perspective of the expert specialist in a traditional historical framework. They do not always engage proactively with the modern communities that occupy (or will occupy) the new spaces that are being created.

As noted above, urban spaces are simultaneously both archaeological and systemic contexts, and they are also dynamic. Some of the most interesting relationships in urban places past and present take place at the margins, in those interstices between formally demarcated spaces, or between public and private spaces (Lutzoni 2016; Pittaluga 2020). These relationships may be more easily explored through non-traditional forms of interpretation and public engagement. Ideally the increasing deployment of high-definition digital recording methods, including three-dimensional (3D) models and 'digital twins', can also serve to generate exciting new tools and approaches for meaningful public engagement (Jacobsen et al. 2021; Gaffney et al. 2025). Dynamic digital interpretation can help make the past more accessible and relevant for modern audiences. Moreover, there are long-lasting and deeply seated relationships between urbanisation and environmental change: the archaeological record can help explore the interactions between human and natural ecosystems (Laubichler and Renn 2015; Roberts et al. 2024. Sometimes, therefore, public engagement may take on a political dimension, whether in support of a particular development or in opposition to the social transformation that it represents (Arcos García 2025).

Urban archaeology offers invaluable insights for understanding the past, but its relevance extends far beyond historical curiosity. Our understanding of the historical experience of urban places can, and should, inform the design and development of places in the future. Most of that historical experience is about incremental change, small in scale and relatively slow in pace. The urban fabric, the grain of streets and properties, is resilient and long-lasting, and even, as in the case of Lübeck, can be revived when seemingly lost (Dubisch 2025). Even quite dramatic remodelling in the past has usually been confined to small areas, as Philippe Sosnowska articulated at the symposium using the Grand Place in Brussels as an example. Of course there are a handful of exceptions to this picture, for example post-1755 Lisbon, Haussmann's Paris, modern Tiranë, but generally the process of European urbanisation has taken place on a human scale. We must hope that our understanding of the complexities of how European urban spaces have evolved and shifted, and the ways in which people have navigated around those spaces, will help inform the development of future cities.

The archaeological evidence overwhelmingly shows that cities are at their most functional when they balance connectivity with open spaces, fostering social interaction and economic activity, in other words the process of 'energised crowding' discussed above. Dysfunctional cities, in contrast, tend to be characterised by fragmented spaces, disconnected infrastructure and a lack of coherence between different parts of the urban landscape. As urban populations continue to grow, cities will face new challenges in terms of sustainability, infrastructure and social cohesion. The individual case studies in this volume highlight the collective value of archaeological understanding of urban development in the past. From this it should be possible to create a widely applicable framework for studying urban dynamics, land use and social change.

Our work as urban archaeologists and heritage managers needs to be about much more than preserving remains in situ or creating 'archaeological parks' and interpretation panels. Yes, these lumps of stone and brick are important artefacts of the past. They represent the past, but they are not actually the past. They exist in the present, and require interpretation to make themselves relevant to people today and in the future. Perhaps we need to be a bit less precious about the physicality of the past, and think more creatively about how we use the stories that our work generates.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.