Cite this as: Zirne, S. and Lūsēna, E. 2025 Archaeological Heritage in the Historic Centre of Riga: Status, Management, Development, Internet Archaeology 70. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.70.4

Riga, the capital of Latvia, is located on the southern coast of the Gulf of Riga, at the mouth of the River Daugava. Today, the city is situated on both banks of the river and covers an area of 307 km2, but the oldest part of Riga, Old Riga, is at its centre, on the right bank of the Daugava. Historically, Daugava has been an important international trade route between the Baltic and Black seas since the Iron Age. Because of its location on this trade route, from the beginning of the 13th century Riga became an international trade centre, and because of its strategic location and military conflicts, for many centuries it was built as a fortress. This has created problems for the future development of the city.

Systematic and scientific archaeological excavations have only been carried out in Riga since 1938. Previously, during construction works, only artefacts were collected, which later ended up in museum collections. However, the archaeological material obtained so far does provide significant additional information for historians and further research into the history of Riga.

Archaeological investigations of the oldest part of Riga prove that by the 11th–12th centuries two settlements with burial grounds were already located on the peninsula where the small River Riga (Rīdzene) flowed into the Daugava, forming an area suitable for a harbour (Caune 2007). However, with the development of the city, by the 19th century the river had filled up completely.

Its geographical position at the crossroads of trade routes near the natural harbour was a contributing factor in the development of Riga as an important economic centre in the lower reaches of the Daugava in the second half of the 12th century. During the Livonian Crusade, expanding and strengthening the area of activity on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea, Bishop Alberts founded Riga in 1201 as the episcopal seat and centre of religious and military activities. At first, the city occupied an area of about 5 ha. It was surrounded by a defensive wall, which was extended several times during the 13th century. In 1234, Riga covered an area of 28 ha, and remained that size until the 16th century. At the end of the Middle Ages, the ring of the defensive wall was reinforced with 25 towers, of which at least 12 were built in the late 13th century (Figure 1). They were placed approximately every 70–120m (Miklāva 1998). Residential, public and sacred buildings, and residences of the ruling political forces, were built inside the defensive walls. In the planning of Riga, the main streets were derived from existing roads, as well as connecting the main building complexes of the city and the medieval street plan has remained unchanged (Ozola 2024).

In 1282, Riga became a member state of the Hanseatic League, and experienced prosperity during the 13th–15th centuries from trade with central and eastern Europe, which helped ensure the city's economic and political stability. Between 1537 and 1563, in accordance with Renaissance ideas on urbanism, fortifications consisting of ramparts and bastions were built around Old Riga (Krastiņš 2006, 396). Riga's geographical position made it a strategic location in the contests of superpowers for dominance in the Baltic Sea region, and, as a result of the Livonian War (1558–1583), after the collapse of the Livonian state, Riga came under the rule of Poland. Before that, it had gained the status of a Free City for 20 years (1561–1581).

While the geographical location of Riga contributed to the growth of the city, with the construction of ramparts in the middle of the 16th century, the size of its territory was limited. People therefore began to settle outside the fortifications, where, in the 17th century, the suburbs of Riga began to form. During the Polish-Swedish war in 1621, Riga came under the rule of Sweden, and the fortification system of the city was gradually restored and improved. In 1626, the Swedes also completed an outer line of defence around the suburbs, which had grown up in an unplanned manner outside the fortified city. This was a simple timber palisade with 10 redoubts: small triangular projections (Bākule and Siksna 2009, 28). In later years, during the Swedish rule, new suburban planning and fortification projects were developed, although none of them was realised (Figure 2). The Great Northern War (1700–1721) interrupted the process of city and suburb planning and the construction of fortifications. In 1710, Riga came under the rule of the Russian Empire, and the reconstruction of the city and its fortifications after the war took about 50 years.

During the 19th century, with the rapid development of industry, Riga's population grew, but its spatial structure based on previous centuries, with a division between the fortified city centre and the far-flung suburbs, was preserved. One of the factors preventing its development was the fortifications of the inner city and the restrictive regulations relating to them. In the middle of the 19th century, Riga was still designated a 'Russian Imperial Border City with Military Fortress Status' and had to retain its characteristic 18th-century fortification system: an extensive zone of ramparts, moats and bastions (nine bastions, one half-bastion and three ravelins), surrounded by a 400-m wide area containing glacises and esplanades (Bākule and Siksna 2009, 134–135). However, the fortifications became outdated and lost their strategic importance, and in 1856 Tsar Alexander II gave his approval for them to be demolished.

In 1863, the earthen ramparts were dug out and the stone constructions demolished. With the demolition of the fortifications, the city and its suburbs were connected. In 1875, the city architect Johann Daniel Felsko, together with architect Otto Dietze, designed a city development plan for Riga, which was submitted for consideration by the Riga City Council. According to this plan, the fortification moat was to be transformed into a channel with flowing water, and there would be a unified urban design, with wide streets and a system of green spaces. This opened up the potential for Riga to avoid spontaneous construction.

After demolishing the fortifications, parts of the sand and construction debris were levelled, and the rest used to raise the level of the Old Riga streets and form Bastejkalns, while allowing an unlevelled part of the Smilšu Bastion to remain. Construction works began on the sites of the former fortifications, for residential homes, The Latvian National Opera house, the former city gas plant, and parks. In the late 1930s, several blocks of buildings in Old Riga were pulled down to make way for new large-scale public buildings. Then, during the Second World War, almost one-third of the most valuable buildings of Old Riga were destroyed.

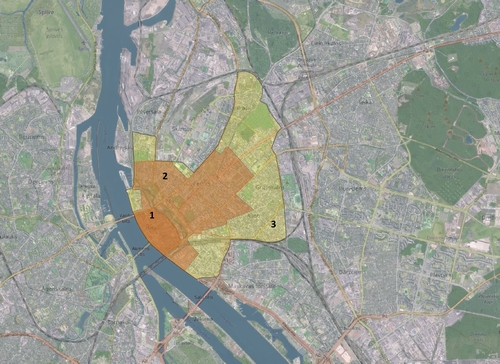

The oldest part of Riga, which until the 19th century was surrounded by ramparts, bastions and other fortifications, is protected as an archaeological monument of national significance: the Old Riga Archaeological Complex (see https://mantojums.lv/cultural-objects/2070). It covers an area of 0.944 km2 (Figure 3).

According to the latest version of the List of the State Protected Cultural Monuments of the Republic of Latvia, approved in 2022, each cultural monument must have defined preservable values, which prove its cultural and historical importance. The main preservable values of the Old Riga Archaeological Complex are the cultural layer, preserved ancient wooden and stone structures, fragments of city fortifications from different periods, cemeteries near churches, and burials in churches. The average thickness of the cultural layer in Old Riga is 3–5 m, in places reaching a depth of 8m (Figure 4). Cemeteries near churches existed until the 18th century, when, in 1773, as part of the fight against the plague epidemic, Empress Catherine II ordered burials to be carried out outside the city limits.

Archaeological excavations in Old Riga have only been carried out since 1938, which is relatively late, because extensive construction work had already taken place before that. This is one of the reasons why it is not always possible to predict the extent of archaeological evidence preserved across the entire area, especially under buildings built or reconstructed in the 19th–20th centuries. Today, its complex status provides comprehensive protection for all archaeological evidence, regardless of its type and degree of preservation. Issues of further preservation and display of discovered archaeological evidence are, however, more difficult to resolve, most often due to ethical and financial considerations.

For example, during renovation works in 2013, a fire broke out in Riga Castle, one of the most important cultural monuments of Old Riga (see https://mantojums.lv/cultural-objects/6594). Riga Castle was originally built in 1330 and then rebuilt several times: in the 15th–16th, 17th and 19th centuries. It has been the residence of the president of Latvia since 1922. In the 1930s, some renovation work was carried by architect Eižens Laube. During the renovation work in 2013, a fire broke out in the attic of the castle (Figure 5). It was estimated that more than 3200 m2 of the castle was destroyed. The parts of the castle that housed the Chancellery of the President, the Latvian Art Museum and the National History Museum. were also affected; although none of the collections was destroyed by the fire, parts of them were damaged by water. After the fire, reconstruction of the castle began. In 2021, a heating stove dating back to the 13th/14th century was discovered at the basement level (Figure 6). It is the oldest, almost completely preserved, hypocaust oven of this volume discovered in Latvia to date. The hypocaust was preserved in situ as a result of the basement redesign, which required additional financing and extended the reconstruction time.

In recent years, due to the large-scale restoration works of churches, the question of preserving the burials discovered within them has also come to the fore.

In 2017, extensive reconstruction works began in St Jacob's Cathedral. St Jacob's Cathedral was built in the 13th century and has been reconstructed several times (Figure 7). It was the first Latvian parish church in Riga, dating from 1523. The church is located opposite the 19th-century building that now houses the Saeima (parliament) of the Republic of Latvia. During the reconstruction, an archeological survey was carried out. Ten, in some places even 11, burial levels were identified in the communication trenches around the church, the last of which dates from the 15th century (Tomsons 2020). Partly destroyed and less damaged burials were located inside St James's Cathedral (Figure 8). After archaeological research, the human bones were placed in a special ossuary within the church, at the location where the 'bone chamber' was located according to 19th-century plans. It is planned to open it to the public, with the entrance covered by a glass wall.

The Old Riga Archaeological Complex is a part of the Historic Centre of Riga, which is a cultural monument of urban development of national importance (see https://mantojums.lv/cultural-objects/7442).

The central part of Riga city was inscribed on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage List in 1997. The description of the object states that: “the Historic Centre of Riga and its buffer zone include a set of authentic cultural and historical attributes significant to its Outstanding Universal Value: structure of historic urban pattern with high-quality transformations of later periods, panorama and skyline, visual perspectives, historic structure, (particularly groups of buildings of the Middle Ages, Art Nouveau and wooden architecture and the scale and character thereof), archaeological cultural layer, public outdoor space, system of greeneries and green areas, historic water courses, waterfronts and water bodies, historic ground surfacing, and historic elements of improvements”. The area of the UNESCO article includes the Old Riga Archaeological Complex, and also the area of the Historic Centre of the City of Riga (Figure 9). The components forming the Outstanding Universal Value are also the preservable values of the cultural monuments.

The historical centre of the city was formed in the 19th century when the city's fortifications were destroyed (Figure 10). The protection of cultural monuments in Latvia is regulated by the law On Protection of Cultural Monuments. The territory outside Old Riga does not have the status of an archaeological monument, but management of its cultural heritage is regulated by the special Law on Preservation and Protection of the Historic Centre of Riga, adopted in 2003. This was necessary because, at the turn of the century, businessmen wanted to develop construction projects in the city centre, ignoring the law On the Protection of Cultural Monuments. The task of the law adopted especially for the preservation of the centre of Riga, prescribes the procedures for the preservation, protection, use and implementation of development projects, and the requirements for the development of spatial planning. According to the law, one of the authentic cultural and historical values in the Historic Centre of Riga that should be preserved and protected is the archaeological cultural layer, which ensures archaeological research outside the borders of Old Riga. The adoption of the Law on Preservation and Protection of Historic Centre of Riga can be considered the most important event of 2003 in the area of heritage protection in the Baltic region. In Latvia, it was a turning point in terms of being the most significant change in attitude and understanding of cultural values in over a decade (Dambis 2017, 48).

At the turn of the century, with growing economic pressure on cultural heritage, several cultural and historical places in Latvia became endangered. The old city and Historic Centre of Riga faced the greatest threats. Both local and foreign developers wanted to realise large, monumental projects. One of the more memorable cases was the plan to build a multi-storey car park in Old Riga, where historical fortifications and the Triangle Bastion were located. The bastion was built in 1727 and existed until 1859, when it was demolished along with the rampart system. Before the start of construction works, small-scale archaeological excavations were carried out, during which the configuration and preservation of the bastion were recorded.

In the year 2000, during archaeological monitoring, the Triangle Bastion was completely uncovered. The stone construction had been preserved in the ground up to a height of approximately 1.5–2.7 m, which is less than half of its initial height (Lūsēns 2002, 261).

The exposed bastion structures hindered the development of the project, so the developers wanted to demolish them. Wide-ranging discussions and disputes emerged between the developers, city council and cultural heritage experts. The press and the public also got involved. After much debate, the remains of the Triangle Bastion were preserved and archaeological excavation of the site continued.

During the archaeological excavations, after removing 3.5–4.2m of 20th-century infill, remains from strengthening the River Daugava's right bank were also discovered, from six different periods. The oldest finds date back to the end of the 14th and beginning of the 15th centuries, while the youngest wooden constructions are dated to the middle of the 17th century–beginning of the 18th century (Lūsēns 2002, 261).

As a result, the project of the multi-storey car park was not realised, but, instead, modern buildings were built, including a supermarket and a restaurant. The exposition of the Triangle Bastion stone constructions was unsuccessful, as it is not noticeable in the overall architecture of the modern building, which seems to point to the site of the bastion but does not highlight its authentic values. Now, the fragments of the bastion are no longer publicly available, because the building contains some office premises that are closed (Figure 11).

Extensive excavation works are planned for construction of the Rail Baltica railway. Rail Baltica is a greenfield rail transport infrastructure project with the goal of integrating the Baltic States within the European rail network. The project includes five European Union countries: Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and, indirectly, Finland. The works are taking place near Old Riga, an area that has been the subject of numerous construction works, at the end of the 19th and in the 20th centuries: railway and street construction, and various underground communication systems. According to both historical plans and drawings of the city, the Šēra Bastion, one of the city fortification elements, is situated in this area. However, there was no certainty about how much archaeological evidence had actually been preserved.

Due to the construction of the new railroad in 2023, reconstruction of the nearest street infrastructure began. Surprisingly, even after extensive construction works in the past, remains of the city fortification system were discovered. Fragments of the bastion were already preserved at a depth of about 50–70 cm under the street surface (Figure 12). Initially, the technical specifications of the construction project meant that the bastion had to be levelled completely. After the discovery of the remains, however, solutions were developed to accommodate them. The bastion fragments were preserved in situ, and only its upper part of about 30 cm was dismantled, which was necessary to ensure the functionality of the street.

In the Historic Centre of Riga, there are various known cemeteries dating from the 14th to the 18th centuries. As part of various construction projects, some of them have been archaeologically investigated. However, despite the previously discovered archaeological evidence, the developers did not and still do not believe that anything else can be discovered in these specific areas.

The most extensive archaeological excavations were carried out in the so-called St Gertrude cemetery in 2006. Situated in the centre of Riga city, the area was not fully built on until the second half of the 19th century. According to historical sources and maps, St Gertrude's church and its extensive churchyard date from the 15th until the 17th centuries. A new project planned a multifunctional building with an underground space on this site.

Within an area of about 200 m2, more than 709 graves with 719 individuals were discovered (Lūsēns 2008, 144). Due to the long-term use of the relatively limited area as a cemetery, the density of burials increased over time (Figure 13). Six layers of burials were found, as well as 8–9 layers of mass burial trenches. Five bone pits, 'chambers' from ruined graves, were also found, with more than 2000 individuals represented. Two sites of mass burials were uncovered in the investigated churchyard area. The deaths could have been caused by deadly infectious diseases of many kinds. It is believed that both mass graves discovered in the St Gertrude cemetery could have included people who died in 1601–1602 from starvation or the plague, or victims of the 1623 plague epidemic (Lūsēns 2008, 148).

During the archaeological excavations, only part of the former cemetery of St Gertrude was investigated. Due to financial reasons, the project was not completed, and the area remained undeveloped. Currently, a new construction project is being planned, a complex of buildings without deep foundations, such that the ancient burials should not to be affected by the work and archaeological research is not needed.

A completely different situation has arisen on the left bank of the Daugava. This area is not located within the Historic Centre of Riga, but borders on its protection zone. According to historical plans, on the left bank of the river opposite Old Riga was the 17th–19th century fortification called the Kobronskanst. Its origin is associated with the Swedish army that built a fortification here in 1621. The Kobronskanst existed until the middle of the 19th century, and was rebuilt and extended multiple times.

Liquidation of the Kobronskansts began towards the end of the 19th century. During the early 20th century, a city park was built on the area, and later a system of family gardens. After these previous transformations, there was no archaeological or visual evidence of the Kobronskanst left.

Currently, new buildings for the Academic Centre of the University of Latvia are gradually being erected. Before the construction works, it was decided to carry out archaeological test excavations to find out if there were any remains of the Kobronskanst (Figure 14). The authors of the archaeological investigations concluded that only some remains of 17th-century wooden structures and artefacts had been preserved, and a large part of the cultural layer and the structures of the Kobronskanst were possibly destroyed and levelled at the beginning of the 20th century (Šnē 2012, 171–172). However, during the construction works, archaeological monitoring was also carried out. In 2014, extensive archaeological research and construction works began. It was stated that the cultural layer in the area of the fortification was 2.5–3.0m thick, but, in some places, its thickness exceeded 4.0–4.2m (Lūsēns 2016, 119). During this archaeological research, multiple remains were found, dating from the period between 1621 and the mid-19th century, when the fortification was populated (Figure 14). These remains include 11 buildings, rows of posts along the moat, a road laid out with branches and structures of military importance, all belonging to the fortification's outer wall and the base of the transport gallery.

As a result of this archaeological research, one year later, in 2015, the constructions of the Kobronskanst were included in the list of state-protected monuments (see https://mantojums.lv/cultural-objects/9223).

In the Historic Centre of Riga, archaeological evidence of the city's history has been discovered in various places and at various scales. Its preservation and research are ensured within the framework of current legislation. In Riga, as far as possible, archaeological remains are preserved in situ. However, in recent years, despite the legal backing, problems have arisen in relation to large construction and reconstruction projects. Developers are increasingly looking for opportunities to use underground spaces in new projects, even in the territory of Old Riga. On the one hand, this opens up the possibility for new archaeological research, but on the other hand, the amount of archaeological evidence preserved in Old Riga is gradually decreasing.

During the writing of this article, discussions have arisen about the need to change the Law on Preservation and Protection of the Historic Centre of Riga. The situation is reminiscent of 20 years ago, when economic pressure threatened Riga's cultural heritage.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.