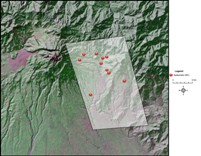

Figure 33: Map of 2000-2005 study area

The adventure and riches associated with gold largely fuelled the 19th-century looting of Chiriquí antiquities. The assumption of commonality between social valuation of pre-Columbian gold objects in the past and present, however, is clearly problematic (Falchetti 2003; Gaitán-Ammann 2006; Ibarra 2003). Gold was possessed by both elites and commoners in the pre-Columbian past (Londoño 1989) and replicas of gold objects cut from yucca could function equally as well in a burial context and the afterlife (Gabb 1913; Holmberg 2009, 197; Joyce 1916, 104). As several authors point out, gold was perceived in very sensuous ways in the pre-Columbian past, using additional valuations such as through odour (which is derived from the copper used as an alloy for the gold) to supersede the western emphasis on the metal's lustre, purity, or monetary value (Gaitán-Ammann 2006, 241; Saunders 2003).

I'd like to somewhat provokingly suggest that the emphasis on gold and whole ceramic vessels that characterised the late 19th-century gold rush – combined with the common early 20th-century knowledge of the vast amounts of material that were 'dis-placed' from the area during that gold rush – diverted archaeological interest from the area at a formative point in pan-American archaeology. Despite the obvious importance of the isthmus as a land bridge between North and South America (see Cooke 2005), influential early and mid-20th-century researchers such as Gordon Willey visited but soon left for Mesoamerica or the Andes to carve out their academic careers. These researchers subsequently nurtured graduate students who worked in those same geographical areas, became mature archaeologists, and nurtured their own graduate students who followed suit. While firmly associated with a rich pre-Columbian material culture in the 19th century, Chiriquí gradually began to experience archaeological obscurity.

Relatively little systematic archaeological fieldwork has been conducted in highland western Panamá to date, with the most sustained, published project being that by Olga Linares and Anthony Ranere (1980; see also Shelton 1984) on the western flanks of the Volcán Barú. I conducted the first sustained archaeological project on the eastern flanks of the Volcán Barú in the vicinity of the modern town of Boquete; one primary intention of the online delivery of this article is to make the field data I collected between 2000 and 2005 accessible to other researchers.

I worked with a small team of paid workers and volunteers from the local community. My fieldwork research universe was a 240km² area on the east slopes of the Volcán Barú though the primary area of artefact collection can be contained in a polygon of roughly 40km² along the Rio Caldera. We focused upon an area north-east of the sites of large-scale 19th-century looting conducted by J.A. McNeil, though the area has also subsequently sustained heavy interest from professional and avocational looters. Using surface survey, shovel test pits, and excavated test units we recovered domestic, manufacturing, and mortuary artefacts from an estimated 4.08km², or roughly a 10% sample of the area [View Sites in digital archive]. Ceramic chronologies [View Comments] [Boquete area ceramics classification] and Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) dates [View AMS in digital archive] temporally situate the artefacts from the archaeological survey between roughly AD 200 and AD 1300. Ceramics (8257 items) [View artefact summary; ceramic_rims; ceramic_bases; ceramic_handles in digital archive] and lithics (599 items) [View artefact summary; lithics in digital archive] comprised the majority of the material culture recovered and data for these are included with this article. Additionally, bone, casts, historical glass and metal items were recovered and 24 petroglyph sites [View petroglyphs in digital archive] were identified, though these lie outside the scope of this article (see Holmberg 2009).

The comments facility has now been turned off.

| Ceramic typologies have yet to become uniformly defined or applied in the Chiriqui culture area. This project drew upon typologies developed through prior fieldwork in Chiriqui as well as museum collection studies (Corrales 2000; Linares and Ranere 1980; MacCurdy 1911; Shelton 1984). I welcome debate, input, dissent, or data regarding the way I classified the ceramics. | Karen Holmberg |

| I think the distinction between value in the artefact market and value in the cultural landscape is a very important issue that this article brings to light. Placing an emphasis on, for example, gold over stone tools in the market has a very negative impact on what we choose to remember and what we choose to preserve. The looting and selling of artefacts undoubtedly removes many cultured objects from the landscape, but it is useful to remember that not everything is removed. As the volcanic rocks in Chiriqui have shown us, there is often plenty of value in what remains. | Kelsey Broderick |

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s)

University of York legal statements | Terms and Conditions

| File last updated: Mon Oct 11 2010