Cite this as: Mytum, H. 2018 The Iron Age Today, Internet Archaeology 48. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.48.10

The contributions in this issue reveal the massive amount of data now available regarding Iron Age enclosed settlement in Wales and, in some regions such as the north-west, significant numbers of the unenclosed elements that formed the settlement pattern in the Iron Age. Thanks to investment in walking the landscape, aerial photography, geophysical survey and excavation, there is a baseline of information on the distribution and types of enclosed settlement and examples of high-quality site-based data, often revealing complex site histories. These are our resources from which to extract meaning about the past — but what can actually be said about the Iron Age from all these data? What are the next stages in moving towards greater understanding? And what is the current management and presentation of the Iron Age to the public in Wales? We live in a world of diverse audiences — by language, faith, ethnicity, cultural background — and our work, both academic and public-facing, has to be relevant to a range of consumers. This contribution reviews the current state of knowledge and its uses so that we can develop strategies to improve the data further but also communicate what this can tell us about this important part of the Welsh past.

The other contributions reveal the thousands of sites now known, but the geographical distributions and the relative frequency of site types still requires some critical evaluation. Thanks to investment from Cadw in enhancing the Historic Environment Records for all regions of Wales, there is now a uniformity of terminology and updating of records for known sites that creates a secure basis for further study. However, recent aerial photography campaigns (notably by RACHMW) continue to build on those since the 1970s to reveal ever more sites in parts of the landscape previously resistant to yielding up their secrets. This is ongoing, and every year newly discovered sites are recorded; in some years with ideal weather conditions for cropmarks the annual increase can be substantial. Other areas, probably also settled in later prehistoric and subsequent periods but as yet little known, may require alternative methods of reconnaissance. The Iron Age of south-east Wales are under-represented in this issue, but this has been partially remedied with the publication of a substantial study of the Vale of Glamorgan (Davis 2017). The Atlas of Hillforts of Britain and Ireland has provided an up-to- date distribution and summary of existing information, and the academic monograph associated with this project is eagerly awaited.

It is clear that in some upland and other long-uncultivated landscapes the opportunities for LiDAR are considerable, and may even recover evidence for open settlements and field systems. Extensive geophysical survey of landscapes rather than known sites may also reveal some forms of open as well as enclosed settlement; location of small sites where pollen sequences may survive would greatly intensify our understanding of the landscape use within which the sites functioned. Waterlogged sites may also reveal deposition of artefacts or human remains that indicate ritual activity; the metal-detector find of bowls, strainer and nearby wooden tankard from a bog near Langstone, Newport, Gwent, is just one example of a recent find that indicates that the famous and unusually large hoard from Llyn Cerrig Bach (Fox 1946) should not be seen in isolation, and Welsh equivalents of the ritual timber causeway at Fiskerton, Lincolnshire (Parker Pearson 2003), are likely to be found in due course. Special function sites such as for ironworking, as revealed at Bryn y Castell (Crew 1986), possibly also laden with ritual as well as economic significance, are other aspects of the landscape pattern that are yet to be well understood.

While very occasionally further hillforts and promontory forts will be identified on the ground, or historic sources may be re-located that indicate ones now completely destroyed, it is the smaller enclosed settlements that are most likely to continue to be found in numbers. This is an important process of discovery that must continue, increasing the density of settlement in areas already with many sites, but also extending distributions and dealing with apparent gaps. However, it is with the unenclosed components in particular that archaeologists have the greatest challenge. The particular form of earthwork and stone-built open settlements in north-west Wales which has allowed them to survive as surface features may be particular to that region (see Smith this issue), but the very density of such sites, and their clear importance in the overall formation of settlement and social structures that also included enclosed farmsteads and hillforts, acts as a reminder of what is hinted at by the extremely fragmentary evidence elsewhere. Throughout this collection of studies the spectre of the unenclosed settlement dweller at the feast of the enclosed limits our interpretative ambitions. Two alternative interpretations of the origins of the Castell Henllys inland promontory fort highlight the very different narratives that are possible, depending on what other Iron Age settlement, and by implication population density and social systems, operated before and during the construction and occupation of known enclosed settlements (Mytum 2013, 314-20). The challenge of interpreting social structure is discussed at greater length below. The quality of the data on the sites that we already know has never been greater; the challenge is to find ways to initiate step-changes that will allow the actual past landscape structure and settlement pattern to be revealed.

In many regions of Wales it is now possible to discuss the enclosed components of settlement with some degree of confidence, though as more excavation takes place it is clear that the diversity of site function and chronology varies greatly; in Pembrokeshire, for example, excavations at Berry Hill, Newport, did not indicate a settlement with a similar sequence or function to that of the nearby and morphologically and topographically similar site of Castell Henllys (Mytum 2013; Murphy and Mytum 2012). In the Welsh and English Marches, it is possible to combine settlement evidence with that of ceramics, which gives a further dimension to the ways in which cultural and economic connections can be identified (Morris 1994).

Where research has been intensive, and the data quality sufficiently high, it is clear that many sites have complex histories, even if only occupied for a few centuries or even less. Archaeologists tend to write generalising narratives based on a small number of case studies, to create overarching accounts of the past. This we should continue to do, in the full knowledge that these are always provisional, and based on our assumptions and expectations of the past as well as the nature and extent of the data presently available to us. But we should also recognise that each place could have its own form of unique and special history, a narrative of changes in size, function, form and meaning that has value in and of itself. The way in which unique features of form and sequence can be examined in relation to location and detailed consideration of the topographic context is emphasised here by Driver (2013; and this issue).

The increasingly complex excavation and recording methods, the integration of environmental and soil science, and the computer storage and potential for manipulation of data means that the evidence now available for those sites where extensive excavation has taken place is enormous. Although many of the settlements of concern here lie within regions where the artefact record is extremely limited, which does constrain some forms of analysis, it does allow structural and stratigraphic aspects of the data to be explored to their full potential. Many excavation reports describe the main structural periods of a site, but detailed analysis can reveal the patterns of small changes, the ways in which daily, seasonal or even occasional cultural practices operated within the settlements. The nature of daily lives, the social and cultural frameworks of living in a particular place at and over particular times, can all be explored through the high-quality data now being recovered from excavations across Wales. As these particular narratives are exposed — and the site biographies are written — it will be possible to move beyond the particular to seeing what the various histories share, and where and why they differ. For some embedded in an empirical tradition of data recovery and management this may seem too ambitious and unverifiable, but methodological and theoretical shifts in recent years, applied in elements of both prehistoric and historic archaeology, could be usefully applied to the rich and diverse data now available for later prehistoric and early historic Wales.

For the enclosed farmsteads with well-preserved sequences of structures, such as those around Llawhaden, Pembrokeshire (Williams and Mytum 1998), the published evidence indicates the complexity of the sequence, but the archive of stratigraphic and plan-based analysis reveals numerous variations over time that have been traditionally merged in phases for publication. As archaeologists begin to consider the lived experience of those who occupied or visited such settlements (Murphy and Mytum 2012), this level of detail can be utilised in new and revealing ways. First considered by historical archaeologists with the benefit of documentary sources (Groover 2004; Rotman 2009, 181-89), it is also possible for those studying the Iron Age to consider generational change, particularly with AMS dating and sequences that allow tightening of chronologies with Boolean statistics, as exemplified at Broxmouth, East Lothian (Armit and McKenzie 2013). The excavated data from a number of Welsh sites could be reconsidered in this light, and will reveal how further excavations can recover data that can be used in such interpretations. Indeed, the fascinating environmental analyses already achieved for Welsh Iron Age sites (Caseldine this issue) can also be considered in terms of short-term actions as well as long-term trends, and also through intra-site spatial analysis to throw light on how practices were followed in different parts of the settlement. Even with few artefacts, some sites can reveal spatial patterning that can be informative, as seen at Walesland Rath (Mytum 1989).

Some widespread trends can be seen from all the data, in terms of a set of generalised settlement forms across Wales (and indeed as an integral part of a repertoire seen more widely across the British Isles). Moreover, shifts in land and material culture use can also be discerned, and while some aspects of the grand pattern occur at the regional level, others apply across the whole of Wales and beyond. These include aspects of later prehistoric culture that are widely present and, perhaps equally telling, those that are absent. Some are very rare, and we need to consider whether that is because they always were, or whether differential survival creates that impression for us today.

The development of settlement forms such as large enclosures and palisaded settlements in the Late Bronze Age sometimes led to the same locations being continued or re-occupied in the Iron Age, though others appear to have been abandoned for good. The early Iron Age in Wales is particularly sparse, but it seems that many of the smaller enclosed farmstead settlements appear from the middle Iron Age, and in all regions the great majority belong to the late Iron Age and many continue into the Roman period. Indeed, during the later Iron Age it would seem that many, if not all, regions with agriculturally productive land (whether for arable or pasture) were fully occupied, with a density of settlement reminiscent of early modern times if an element of unenclosed settlement is also assumed. Unlike regions such as the Thames Valley (Lambrick with Robinson 2009), the farmsteads were not connected by trackways and surrounded by field systems marked by ditches substantial enough to be seen as cropmarks, but that does not mean that the landscape was not structured with fences and hedges, possibly also with stone walls or banks in some areas. Some of the palaeobotanical materials could be interpreted as being derived from hedges, and ditches are not necessary for landscape management. The alternative is that the landscape was largely open, though it is clear that managed woodland must have been extensive to support the construction and firewood requirements of this density of settlement.

Regional differences in shape and topographic location suggests cultural preferences, as these rarely have clear functional advantages. Hillforts vary greatly in enclosed area and scale of the perimeter earthworks, but all reflect considerable investment in construction, creating usually highly visible monuments in the landscape, as explored by Driver (this issue). Relatively few sites have been excavated extensively enough to understand their chronology and functions, but they are clearly not all contemporary, nor were their roles identical; some seem to have dense occupation while others have few if any internal structures, though they could have been used for seasonal camps. Multivallate sites may reflect major investment at one phase of building, but where there has been sufficient excavation the picture is often more complex, and suggests multi-period construction, and the visible earthworks may never have all been in use at the same time. Moreover, earthwork continuity may not match use and occupation of sites, with the enduring earthworks allowing intermittent site use over centuries, which can only be understood with extensive excavation and high chronological precision.

The enclosed farmsteads vary in scale from simple univallate sites to complex multivallate ones, though the same issues of phasing of construction apply to these sites as they do to hillforts. Most sites are sub-circular, with the 'banjo' enclosures with ditched approach and concentric earthwork being a particular subset of these (and may have been elsewhere defined using hedges and fences). Sub-rectangular and rectangular sites, once assigned to the Roman period, are now seen to develop in some areas in the later Iron Age, and small concentrations of these may suggest a particular identity being emphasised through settlement form; such evidence as we have from the interiors suggests similar structural forms to those of other settlement sites.

The structural forms within Welsh settlements comprise the same building blocks of architecture seen not only across all of Wales but also much of England. The dominant structure is the roundhouse, either the double-ring house with wall line and inner ring of earth-fast posts (Guilbert 1981), or one with no internal posts; internal features may include hearths (Ghey et al. 2007). While many houses were timber, examples with stone footings or rubble walls occur in some regions, and in some areas many of the houses have internal stone-lined drains, as seen in some other parts of Britain. Many houses, however, are not confined to any one region and suggest a shared grammar of building that was applied widely across both space and time within the Iron Age. A small number of rectangular structures, most notably at Goldcliff (Bell and Neumann 1997), hint that other structural forms may also have been more widespread than as yet realised. Welsh sites do not reveal the use of storage pits, but numerous four-post structures have been found, indicating another British Iron Age structural element being part of the Welsh repertoire. In some of the Marches hillforts many four-posters can occur on a single site, sometimes in distinct zones (Guilbert 1975). Most but not all farmsteads also reveal one or more four-post structures, indicating that if storage is their function this was dispersed, even if some hillforts may have acted as more central collection points for surplus. Hillfort and some farmstead gateways were constructed with massive earth-fast posts, often associated with stone revetting of earthworks and enlarged ditch terminals at the entrance; in the middle Iron Age some hillforts were also supplied with what have been termed 'guard chambers', though their function is still uncertain (Bowden 2006; Mytum 2013). The earthwork and structural elements of entrances vary from simple gaps with no gates through to complex approaches through several large earthwork features and massive gateways. It would seem that it was culturally significant to control or at least physically mark entry and egress through certain points in many settlement perimeters, but that some access points were not elaborately defined suggests no simple and overarching explanation.

Wales has been a leader in developing educational resources linked to the Iron Age, in part due to the presence of prehistory and the role of the Celts within the Key Stage 2 of the Welsh National Curriculum for History (DCELLS 2008). The concept of the Celts as the inhabitants of Iron Age Wales has become a well-established aspect of interpretation, though the use of the term Celts within Iron Age archaeology is not without its critics, and the debate is ongoing. Initial critiques came from established as well as younger scholars, with a number of reasons why it was inappropriate for the recent use of the term linked to language to be applied to enigmatic Classical uses of the term, and yet again from that to material culture of the Iron Age (Collis 2003; 2011). With the re-evaluation of the early medieval documentation in terms of date and sources, it has become clear that the assumption that a substantial Iron Age element has survived within these early texts is unlikely. As a result, the usefulness of the term Celtic has been challenged, as implying forms of linguistic and social continuity that is clearly at odds with the divergent nature of settlement and most portable material culture, if that of the Iron Age and early medieval periods are compared. Moreover, assuming a static concept of an innate Celtic social and cultural tradition contradicts the evidence for significant social change within the Iron Age itself. However, Karl has recently reaffirmed the Celtic link and its relevance for the Welsh Iron Age, and has set out his arguments in a format designed to counter previous criticisms (Karl 2008; 2011). While this has introduced new elaborations of the linguistic data, those who were already sceptical have not been convinced (Collis 2011), and it is likely that this debate will continue for the foreseeable future.

Despite these important divisions of opinion with regard to the use of the term Celts, it is likely to remain an important word for the public in connecting the present with the Iron Age past. With its cultural and political value linking the pre-invasion (of both Romans and Normans) Iron Age past with the contemporary devolved and linguistically distinctive Wales of today, it provides a way into discussion of these issues at whatever level, and to whatever degree of detail, may seem appropriate in the context. Indeed, it has already provided a recognisable and valued part of Welsh heritage, which has allowed some institutions to stimulate latent demand for educational resources.

The National Museum of Wales provides training for teachers and downloadable resources from their web pages, as well as opportunities for visits to the galleries to see a wide range of Iron Age artefacts. For many years a reconstructed farmstead was available for the public, and particularly school groups, at St Fagans National History Museum (Figure 1). The individual reconstructed buildings were based on excavated evidence, but drawn from different sites and the enclosure itself was generic; its setting in a relatively damp location on the edge of the site largely devoted to original (though largely moved and restored) buildings from the last few centuries created a slightly discordant context, but once at the site the children could be immersed in the relevant educational opportunities. The National Museum has thus provided important support in understanding the Iron Age, particularly for those schools lying in the most densely populated part of Wales. This reconstructed site has now been removed, but a replacement — based on the excavated site of Bryn Eryr, Anglesey (Longley 1998) - is part of the major HLF-funded Making History project at the museum and is now open. Rather than timber, wattle and daub walls, this reconstruction has 1.8m thick clay walls and has the two roundhouses conjoined (Burrow 2015).

Castell Henllys in Pembrokeshire is the site that has provided the longest-lasting and most dedicated presentation of Iron Age life in Wales, and has the advantage of being set in a rural location and is an extensively excavated site where there are also reconstructed buildings on their original foundations (Mytum 2013). The excavations, reconstructions and public interpretation have run concurrently, developing from private ownership to being managed by the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park (Mytum 1999; 2004). Under the latter's direction, a substantial schools education programme has been developed, together with a range of educational resources including teachers' packs and visual aids (Bennet and Owen 2004). The education programme is closely linked to the National Curriculum (Mytum 2000), ensuring relevance to schools, with a range of on-site activities inside and around the reconstructed buildings, which provides an atmospheric and sensually stimulating learning environment (Figure 2). Skilled facilitators provide training and support, in either Welsh or English, and many schools prepare or follow up with a range of cross-curricular activities. While the attraction is the link to the Celts element of the history curriculum, the advantage of the Castell Henllys experience is that this can be used across a range of subjects including art, language, geography, mathematics and religion.

There can be challenges in balancing schools provision with that for other members of the public, and this can be seen at Castell Henllys (Mytum 2012). The children are enabled to imagine life back in the Iron Age, but the public are in the present and want to understand what it was like in the past, and how we know what we do. These are not issues for the children on the visit (though how we know about the past can be part of what is covered at other times), and this does provide a challenge for both sectors of the audience, and also for the interpreters — in dealing with the public they are in the present, for the children, in the past. These challenges for costumed interpreters are well known across the heritage industry, and there is no easy solution to this. Indeed, being 'in role' has particular dilemmas when so many aspects of the Iron Age are unknown or being challenged by current critiques (see section 6). Indeed, even what roles should be gendered is being investigated, albeit using the regionally and temporally limited British Iron Age burial evidence (Pope and Ralston 2011).

Castell Henllys has four reconstructed timber roundhouses with conical thatched reed roofs (Figure 3), and a four-post structure with a raised platform on which is a small version of a roundhouse; it is interpreted as a storage facility (Figure 4). The earthworks have been somewhat modified and the entrance with its first phase of guard chambers marked out, though in timber rather than stone. Some of the locations of unreconstructed roundhouses are marked out, but there is a risk that the public will neither appreciate the gateway nor the density of structures within the interior for most of the fort's occupation. Nevertheless the structures provide a potent link between the present and a putative past, and the public generally see these as speculative and therefore engage with interpreters and use their own ethnographic experience to challenge or build upon what is provided on site.

There is little doubt that, for all the critiques of those academics who deconstruct on-site reconstructions (Grufludd et al. 1999; Townend 2007), these create stimulating experiences that are not treated by the public as past reality but as a trigger to stimulate discussion and increase awareness of the sophistication and problem-solving of Iron Age peoples. Indeed the recent dismantling, excavation and ongoing rebuilding of the first roundhouse to be reconstructed revealed much important information about both the resilience of the structure and the archaeological traces created by 35 years of a building's use (Figure 5). The visitors who saw this process of renewal under way were once again engaged with the archaeological process that only is achieved when there are more than earthworks to see.

The consideration of lived experience, and impact of lifestyle on landscape and environment, can be explored through experimental archaeology that can be conducted alongside reconstructions and site interpretations. The visual impact of structures and the varying effects of changing elements within reconstructions and the use of art in their decoration reveals how varied the experience could be, even from the same archaeological evidence (Mytum 2003). Moreover, the resource implications of construction have become clear from the reconstruction of buildings and applying these principles to other features such as palisades (Mytum 1986; 2013, 110-13).

There are many positive elements in the existing public presentation of the Iron Age within Wales, but there are some challenges. One is that many sites have no on-site interpretation, and are rarely even signposted as sites, even if footpaths (including coastal paths) make them accessible to the public. Moreover, many regional museums are hard-pressed to display the period given the paucity of finds from local sites. The greatest difficulties, however, have been revealed only too clearly at Castell Henllys, under the pressure to provide information on the Iron Age (as opposed to the archaeology of the Iron Age) to support the education and public presentation programme, and in answer to questions from teachers, schoolchildren and the other visitors. As discussed in section 6, many of our assumptions about social structure have been critiqued and shown to be inadequate, but as yet there is great disagreement about what to put in its place and what that implies as we make sense of the rich Welsh archaeological settlement data for the Iron Age.

The project that underlay the collation and assessment presented in this collection of articles was sponsored by Cadw as part of a process of resource enhancement, to ensure that this culturally important resource could be recognised and managed in a changing world. The study of enclosed sites involves a range of reconnaissance and monitoring strategies from the ground and the air to ensure that the current state of monuments can be evaluated. Moreover, the assessment of below-ground evidence through geophysical survey, followed by selective excavation, has enabled evaluation of the state of preservation of deposits and cut features so that appropriate management regimes can be negotiated with landowners. The work in west Wales has revealed that a surprising amount of structural evidence can survive in the interiors, and in some cases there can be more than cut features in sunken areas below the reach of the plough (Murphy and Mytum 2012). The information collected in these field programmes can therefore serve a number of uses, from ongoing management and protection, through awareness of the need for more intensive mitigation, to greater understanding of the Iron Age. This awareness can inform subsequent management plans and negotiations with farmers.

The management of Iron Age sites has often largely been incidental, with most remains the result of inertia and land uses that allowed continued survival. Greater intensity of use, for agriculture and leisure activities such as walking and motor biking, as well as threats from development, has meant that in recent years more attention has been paid to the resource. National Parks across Wales consider threats including erosion, but the most high-profile cases of management have been elsewhere, notably at Tre'r Ceiri, Gwynedd (see Smith this issue and in the Heather and Hillforts multi-disciplinary project in the Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty of the Clwydian Range in north-east Wales (Anon. 2011). This initiative has also raised public appreciation and understanding of hillforts in this region through site interpretation, public participatory events, and web-based information.

The interpretation of the data from Wales can continue on existing lines — filling gaps, developing the existing narratives with greater chronological precision and with ever-finer classification and distribution. It is likely, however, also to take some dramatic new turns as our wider understanding of later prehistory in Britain and western Europe is transformed by new ways of thinking about the past and reworking and reordering the data in innovative ways. Already the Wessex-centred view of settlement development has been undermined by intensive research in other parts of Britain, not least in Wales. The concepts of tribes as mentioned in Classical sources, and the idea of a hierarchical chieftain leading local groupings have been assumed by many academics and field archaeologists (Arnold and Gibson 1995; Cunliffe 2004; Davies and Lynch 2000). A range of emphases are visible within the contributions here, with some evoking tribal structures (see Ritchie and Smith this issue), others using kin groups (Murphy this issue); the Silures of south-eastern Wales has been used by several recent scholars (Gwilt 2007; Howell 2006; Lancaster 2014). These frameworks are now under challenge, however, as the Classical sources are critiqued, and they probably reflect only the immediate pre-Conquest situation and, moreover, only how that was perceived by the invaders. Evidence for most of the Iron Age, previously structured within these paradigms, could be interpreted in very different ways. This model of a late shift in structure has recently been proposed for the Silures by Lancaster (2014), who suggests a decentralised political structure of clans (though themselves hierarchical) that only join together to form the Silures in the face of the approaching Roman threat. Evans (this issue) is even more equivocal regarding the significance of the tribal grouping as a meaningful political entity.

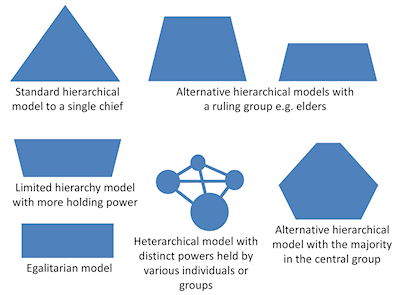

Review of Iron Age social structure was initiated by Crumley's suggestion that heterarchy would be a more appropriate model, where various aspects of power (e.g. military, judicial, religious) were distributed among different individuals and kin groups and at different spatial scales, but not in a framework that led to accumulated power at ever higher levels (Crumley 1995). This approach was linked to other independently developing anti-hierarchy views regarding the British Iron Age (Moore 2007; Hill 1995). Indeed, much of recent scholarship is now moving away from hierarchical models to what Hill (2011) has termed non-triangular forms of society, recognising settlement variation but necessarily hierarchies, limited evidence of marked social stratification, few 'luxuries' or long-distance trade items, and marked regionality in many aspects of settlement form and some items of material culture such as ceramics (Figure 6). The hierarchical model is still espoused for Wales by some, however, with Karl (2011) presenting arguments for continuity that links medieval documentation of social structure back into the pre-Roman Iron Age, linked also to the Celts debate discussed above. The Lancaster model (2014) for south-eastern Wales gives a compromise form, with a loose confederation of internally hierarchical clans.

Another example of the continued evolution in approach to the Iron Age is the way in which the concepts of invasion and migration, evoked for much of the 19th and 20th century to explain change (Hawkes 1959), was avoided or downplayed for most, though not all, cultural changes across Iron Age Britain in recent decades (Cunliffe 2004). However, recent research on burial evidence outside Wales has demonstrated that it is possible to identify movement of individuals over large distances (Jay and Richards 2007), and these concepts require reconsideration, albeit requiring more sophisticated associated arguments than previously, and thereby linking these movements with cultural change. The types of shift — within kinship networks, slaving, military movements or trade to name but a few — are critical in creating very different interpretative narratives and explanations, but clearly these are the directions that we should be ambitious enough to embrace, even if we have to offer alternatives that equally well fit the existing data.

The perceptions of enclosed farmsteads and hillforts have each also been reviewed in recent years, in part linked to the changes in possible socio-political structures discussed above, and such consensus as there was has now been broken. Farmsteads were long seen as subsidiary settlements to the hillforts, within a settlement hierarchy that mirrored that of a hierarchical society (Cunliffe 2004). Alternative views, arguing for a more fragmented and segmented society, saw farmsteads as largely independent, though with their occupants maintaining varying forms of social and economic links with other farmsteads to allow intermarriage, exchange of goods and mutual support (Hill 2011, 244-46). However, in some regions of Britain these farmstead units can be seen to be part of continuous landscapes, and where there have been numerous excavations such as around Danebury (Cunliffe 2000) and in the Thames valley (Lambrick with Robinson 2009) even superficially similar sites have not only different histories but also varied functions, suggesting a much more interconnected world (Davis 2011). In Wales, despite the large amount of data, these varied ways of interpreting the settlement evidence have not yet been considered, though Wigley (2007) has emphasised the long-lived nature of some of the settlements, and what that might imply for the identity of such enclosure occupants.

Hillforts have been, as indicated by their very name, associated with defence and a military aspect of past behaviour (just as the definition of the smaller sites as defended enclosures — as opposed to farmsteads, which emphasises a different role). The ways in which hillforts were constructed has been revealed through larger scale excavations of ramparts — notably in Wales at the Breiddin (Musson 1991) and at Castell Henllys (Mytum 2013), but how this was organised socially, and the reasons for constructing such major features are only now being explored. Some contemporary academics still recognise violence as a major theme in Iron Age society, and that hillforts reflect this and have a significant (though not exclusive) military function (Armit 2007). In contrast, others argue that the non-hierarchical social structures would have worked at a larger level through events that held communal significance, and both the construction and use of hillforts would be part of this process (Lock 2011; Sharples 2010). These contrasting views of the role of the major constructions of the Iron Age are noted by Driver (this issue), but making confident reinterpretation from surface evidence alone is challenging. It is therefore encouraging that current multi-season excavation work at Bodfari and Penycloddiau in the northern Welsh Marches and Caerau in the south-east can explore these issues.

A first attempt at exploring alternative perceptions of the Iron Age and the role of hillforts has been attempted at Castell Henllys; the earthworks of the fort could have been constructed by the local population in response to changing conditions that required this new form of settlement in the area, or inserted by an immigrant group, bringing this feature to the landscape and making a more military statement (Mytum 2013, 314-20). By framing the interpretations in this way, we can begin to consider what data we would need to select between these alternatives, and devise strategies to collect such information, though we may have to accept that — for the foreseeable future at least — we may have to present within professional, academic and public contexts a range of alternatives, each of which may fit the existing evidence and be internally consistent. Where this has been informally trialled at Castell Henllys the public has been receptive and stimulated; in contrast, some professionals have considered that all speculation should be eschewed, retreating into a traditional empirical tradition of description and classification. However, while that is a tool of our trade, it should not be the outcome; we are all familiar with alternative interpretations of both the recent past and the present. Indeed, in terms of lived experience, there were undoubtedly different perceptions and lifestyles, based on gender, age, social role, whether free or enslaved, even if a hierarchical class structure was not in operation (and these elements of social differentiation are not represented in Figure 6, yet are important to consider). We should all also be able to support multiple interpretations of the more remote past, providing each is robust in its own terms; given the excellent settlement and structural data available in Wales and cultural significance of this period, there are bright prospects for exploring these issues in the years and decades to come.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.