Figure 37: Sheep in a modern 'wet' area in the Netherlands. Photo L.I. Kooistra.

Sheep formed an important part of the agrarian economy in the Late Iron Age and Early Roman period. During the 2nd century AD, the proportion of sheep declined in both settlements in Tiel-Passewaaij. A persistent idea in archaeology is that sheep do not thrive in wet areas, and that therefore sheep cannot have been of importance in the Roman Dutch River Area. This is in complete contrast to the high percentages of sheep fragments found in rural settlements in this region. Apparently, the region offered enough dry land to enable sheep to do well, or they coped better with humid conditions than archaeologists believe. Liver fluke may have affected sheep flocks, but never to the extent that sheep keeping was not viable. On modern grassland, liver fluke may be more of a problem because of overstocking. Natural grassland would probably not have supported modern flock sizes. Also, moving animals around during the year and avoiding infested areas may have broken the lifecycle of the parasites.

Although some goats are found in the Roman Dutch River Area, the numbers are always small compared to sheep. There was certainly a market for goats, since the Roman army used goat leather for shields and tents. The small proportion of goats compared to sheep is probably related to climate and geology, since goats require dry conditions.

The total absence of young lambs in the settlement Passewaaijse Hogeweg provides an important clue to how sheep were managed. Sheep spent most of the year at the grazing grounds in the flood basins, and that is where lambing took place (Fig. 37). They may have been accompanied by a shepherd, to protect against theft and wild animals and to prevent them from straying. Sheep were probably brought to the settlement once a year for shearing, and possibly several times a year to select animals for slaughter. Interestingly, young lambs were found in the settlement Oude Tielseweg, indicating that the management of sheep differed between the two settlements. The absence of lambs was also noted for Geldermalsen-Hondsgemet (Groot 2009, 385).

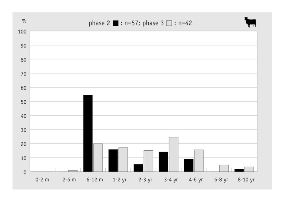

Sheep played a substantial role in Tiel-Passewaaij in phases 2 (50 BC–AD 50, 44% out of the total Number of Identified Specimens) and 3 (AD 50–140, 42% out of the total Number of Identified Specimens). The exploitation of sheep shows an important change between these phases (Fig. 38). While the slaughter peak between 6 and 12 months of phase 2 reflects an emphasis on milk and meat, the older slaughter ages found in phase 3 reflect an emphasis on wool and meat. Assuming that the settlement was self-sufficient in the Early Roman period, an increase in wool production was almost certainly a reaction to market demand.

Figure 38: Mortality profiles for sheep in Tiel-Passewaaij (Passewaaijse Hogeweg), phases 2 (50 BC–AD 50) and 3 (AD 40–140). n is the number of mandibles for which tooth wear has been assessed. Illustration Bert Brouwenstijn, ACVU.

The increase in the proportion of sheep bones and the change in age distribution suggest that the production of wool gained in importance in the second half of the 1st century AD. When we assume that in the previous phase enough wool was already produced to satisfy local demands, this increased emphasis on wool suggests that surplus wool was produced specifically for a market. When we compare the results from Tiel-Passewaaij with those from other rural settlements in the area, we see that a similar pattern is found. High percentages of sheep in the 1st century AD are found in many other settlements in the Dutch River Area. The demand for wool in the second half of the 1st century AD can be related to the Roman army. It is probably not a coincidence that the decline in wool production occurs at the same time that the only legion leaves the region. The Tenth Legion, stationed in Nijmegen since c. AD 70, left the region in 102/104; the number of soldiers in the Dutch River Area declined as a result.

Keeping sheep for wool is more labour intensive than keeping animals solely for meat. While sheep need shearing whether wool is a production aim or not, the market would have required quality fleeces, which were intact and clean. Washing sheep prior to shearing is common practice, and not only cleans the fleece, but also reduces the fleece's weight. Shearing may have been done by a specialist, travelling around the settlements in spring.

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s)

URL: http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue27/5/3.3.2.html

Last updated: Tue Nov 10 2009