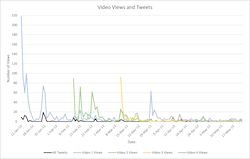

Figure 1: Number of video views and tweets from release date

Though the project produced several identifiable outcomes, measuring its impact has not been a straightforward process. Impact can be defined in multiple ways depending on the sector, and in academia has two dimensions – the internal (academic) and external (business, government, civil society) (Tanner 2012). One of the primary challenges in defining and understanding the impact of social media projects on internet-based audiences is that they are hard to define and may differ from the target audience (e.g. Davies and Merchant 2007; Pett and Bonacchi 2012). The impact of sharing will be different depending on whether academics aim to communicate with other academics and professionals, or with members of a given public (Lake 2012). Between academics, the aim can be described as information sharing and exchange; impact might be measured in citations (Lake 2012; Tanner 2012).

When the goal is public communication, often to raise awareness or interest in a subject, 'open' archaeology online can be viewed as traditional community archaeology through a digital lens (Lake 2012) and there is a need for digital strategies for outreach to be embedded into research projects as standard (Morgan and Eve 2012). Defining the public as an audience remains a challenge. Bonacchi (2012) notes that these might be defined as three separate categories: institutions; groups, people, and communities; and public opinion. An alternative grouping might be those who are interested and informed, interested but uninformed, and uninterested and uninformed. One might question whether social media attracts new audiences or whether it increases the frequency of interactions with an existing audience (Bonacchi 2012). In archaeology, Richardson (2012) contends that there may be somewhat of a closed community on Twitter, with professionals tweeting and retweeting to each other. This is not necessarily to be viewed as negative, as it depends on the intent of the project.

This project was designed with the intention that the videos were easily understandable to non-specialists, but whether they have significantly reached a large number of non-academics on the basis of analytics alone is unclear. Anecdotal accounts are more enlightening and do suggest some level of interest and engagement from people outside the sphere of academe, and in particular a number of reports of the videos being used in teaching/classroom settings suggests that they will reach a younger, student audience. Given the recent completion of the project, impact may be something that is not yet possible to assess.

The first video to be released ('Where did people go during the last Ice Age?') has had the most views, and the number of views for subsequent videos seems in part correlated with the length of time they have been online; the latest video has been up for little more than a month at the time of writing (released 14 April 2013). The number of views also seems to be influenced by other factors, such as how much the researcher promoted it as well as the timing of related news items and blog posts mentioning the project videos. For example, when analytics are presented below, the relationship between tweets and views is not causal, but there does appear to be higher numbers of video views on the day(s) a link is tweeted.

Since this project is part of the Social Media Knowledge Exchange, I'd like to consider some of the responses from varying sources and consider the relationships between the media presence of the project, sharing the videos via social media, and perceived outcomes and impact.

The videos created through the project and its outcomes are likely to evolve over the years, as the contents will continue to exist online and attract more viewers. The videos and project were shared with academic and non-academic audiences in a variety of ways. More 'traditional' media forms included a poster presentation at the 2013 Society for American Archaeology conference, announcements on appropriate academic email listserves (discipline and department-based), and a radio interview of Pia Spry-Marques in Madrid, Spain. The project was also highlighted in a research news article on the University of Cambridge website, a piece that was shared, according to the website, over 100 times on Facebook and over 65 times via Twitter (as of 30 May 2013).

The videos themselves are available through a variety of outlets. They are hosted on the project website, as well as through the SMKE YouTube channel. Downloadable copies have been uploaded to humbox.ac.uk for use in classroom teaching. The poster and links to the videos have been uploaded to the academia.edu website, which has garnered approximately 40 views in just over a month. The Access Cambridge Archaeology blog uploaded one video ('What can diet tell us about social relationships?'), described the project, and linked to the other videos (20 March 2013). Pia Spry-Marques uploaded her video, 'Where did people go during the last Ice Age?' onto Figshare, an open access repository website.

The videos and the project were promoted and shared primarily via three forms of social media: Twitter and YouTube (for which there are analytics available) and via Facebook (no analytics).

Though prefaced as 'anecdotal', these types of response may be indicative of a more lasting impact. A view or retweet does not necessarily mean that the subject matter made a substantive impression. Receiving direct communication and feedback from individuals suggests a higher level of engagement, although passive engagement cannot be dismissed (Jeffrey 2012; Kansa and Deblauwe 2011).Responses from individuals and organisations via Twitter, YouTube, and email were positive and encouraging. For example, retweets added sentiments such as 'I loved this!' or 'great project'. Several original tweets provided video-specific information and feedback, such as

'a SUPERB new digital video on Ice Age [link] by the lovely [handle] - for historians & scientists'

and

'What do bones say about beliefs?' [link] does a great job in explaining the #taphonomy of #humanbones'.

A number of tweets and retweets were from non-archaeologists and non-academics. The project has also received emails from university lecturers and teachers in five different countries using the videos as teaching aids in their classroom, as well as from a heritage organisation and a university-sponsored archaeology database about using the videos in their presentations and outreach. Three out of four of the researchers involved received direct emails from a variety of sources (academic archaeologists, an undergraduate researcher not in archaeology, and an academic not in archaeology) either asking about their research or use of the videos in lectures; one individual sought advice on how to make his own. All of the researchers felt that the project was a positive experience that developed their communication skills and broadened their ideas about outreach. Around the same time her video was released, one participant started an archaeology blog. Another participant commented that she felt that one of the strongest points of the videos is their utility for research done on international material, since they can make it back to people in the country where the research is being done – highlighting the fluidity and ubiquity of audience possible in digital media.

Analytics were available from YouTube (dates and number of views) and the social media aggregator Topsy (dates and number of tweets). One of the difficulties of this type of project is that the data provided here will be outdated by the time of publication, but it is still instructive to consider the viewing trends over time. The analytics presented here are accurate as of 24 May 2013, four months after posting the first video, and six weeks after posting the final video.

On YouTube, views have tended to be the highest on the release date, with steady views in the following weeks (Figure 1).There is a high retention of viewers throughout the duration of each video. Small peaks in views have occurred and appear to be correlated with retweets on Twitter, although other factors are also at work. This includes the 'influence' of the person tweeting the video (i.e. whether they have 200 or 2000 followers) as well as the timing of other media (such as the radio interview and online news article). Two months after the first video release on 11 January 2013, as of 18 March 2013, the first video had over 1,120 views and had been live for over two months; video two had been live for one month and had 530 views; and the newest video (live for one week at that time) had 165 views. Since then, over four months later (as of 24 May 2013) the first video has 1,497 views, with an average number of three views per day in the month of May.

It has already been noted that tweets are not the only social media to affect views, and some small peaks in views occur without any tweets referring to that video on a given day. When someone watches a video on YouTube, the site offers related videos on the right-hand side of the website. Views of previously released videos may have small peaks in relation to the release or sharing of a related video. The videos uploaded to the humanities teaching resource website humbox.ac.uk have collectively had 44 hits and 14 downloads (as of 30 May 2013) and may also have contributed to views on YouTube.

The videos have been viewed in over 65 countries, with the most views occurring in the US and UK. There have been relatively high numbers of hits from the countries in which the archaeological material is derived, namely Croatia (110), Serbia (12), and Peru (9).

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.

File last updated: Tue Sep 3 2013