Archive: An archaeological database of higher-order settlements on the Italian peninsula (350 BCE to 300 CE)

Data relating to historical chronology requires particularly careful assessment of confidence levels. In order to establish how settlement patterns changed over time it is necessary to record not only the duration of each site's occupation, but also how their physical characteristics changed over time. Authors are often justifiably imprecise when dating sites and their features as archaeological data frequently only permit the establishment of broad dating brackets. Conversely, inscriptions sometimes allow monuments to be dated very precisely. Because of the variety in the precision of dating interpretations for each of the chronological categories, they are entered into the database in the form of date ranges using calendar dates. Published dating interpretations are treated consistently so that, for example, 'late 4th/early 3rd century BCE', is always entered into the database as 325-275 BCE, and '4th/3rd century BCE' is always entered as 350-250 BCE. All similarly described overlaps between other centuries are treated identically. Thus published dating interpretations may have been made more precise than their authors intended, but this process is necessary for systematic data entry and analyses. Insufficient information is available to determine the dates of occupation at 25 sites in the database, meaning they are effectively undated. They are nevertheless included because of the expressed belief by scholars that they existed at some point during the period under study. Data are not yet available to establish the start of occupation for 11 sites in the database, and the abandonment for a further 10 sites.

For the dated sites, chronological information is documented in relation to periods of abandonment, destruction events and identified moments of contraction and expansion in settlement size. All of the elements of the built environment chosen as data categories, such as city walls and monumental architecture, also have construction chronologies linked to them in the database. In total, 30 data categories are for historical chronology, although none of the sites have entries against all of these.

Dating in archaeology is a notoriously interpretational process, even when chronologies are derived from scientific dating techniques. A broad spectrum of dating methods has been encountered during this research: from artefacts recovered from stratified deposits, construction techniques, comparanda from other sites, and the interpretations of ancient written sources. Confidence in each chronological interpretation is expressed in the database as levels of certainty that differ slightly according to what characteristic of the settlement is being dated. Because all of the chronologies are collated from published literature, a reflexive approach is required to assess confidence; a sometimes complex interplay of interpretational elements informed the assessment – the degree of confidence expressed by an author; the quality of the scholarly argument; the type(s), quantity and quality of presented evidence. Generally, dating interpretations derived from systematic excavation are flagged with the greatest level of confidence – a 'high' certainty rating – although such dates are, of course, still not guaranteed to be accurate due, for example, to issues such as ceramic chronologies and residuality. Most other methods by which dating interpretations are derived are flagged with 'medium' certainty. A 'low' certainty rating is given if support for a dating interpretation is particularly weak, including cases where no two authors agree, or if extreme uncertainty is expressed by authors. Disagreements on dating among authors are commonplace and alternative dating interpretations are documented in the database. In such cases, the choice of the dates used for the analysis is based on the approach described in the previous section on data confidence. A 'low' certainty rating is also assigned to all incomplete date ranges, for example, when the date of a settlement's abandonment is known but when its foundation date is not, or vice versa. In such cases, the missing date is entered as 'undated'. A final category of 'unconfirmed' is assigned in cases where no supporting argument or evidence accompanied the published dating interpretation.

For sites that have not been subject to intensive open area excavation, the dating evidence can sometimes be uneven. This means that between the known dates of foundation and abandonment, the available dating evidence does not cover all intervening periods. All such sites are flagged with 'medium' certainty because of the risk that the lacunae might represent one or more periods during which the settlement was abandoned.

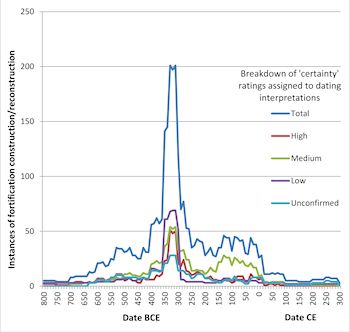

The advantage of including all forms of published dating interpretations, even those without supporting arguments, is that it permits a peninsula-wide survey and regional comparisons of how settlements are currently dated. The resultant patterns indicate that confidence in dating interpretations is not evenly distributed over time (Figure 5). Variability, however, is closely connected with chronological resolution; over periods of multiple centuries, patterns among the confidence categories do not differ significantly, but over periods of decades, much more notable differences are apparent. The full results and implications are presented in forthcoming publications relevant to the specific historical periods.