Found in north-west Spain and Portugal, western Wales, western Ireland and Scotland, chevaux-de-frise are a feature of some Iron Age sites, their distribution demonstrating cultural contact along the west coast of Europe during the Iron Age (Cunliffe 2004; Harbison 1971). Chevaux-de-frise consist of a band of upright stones outside the main defensive circuit of a hillfort or defended enclosure (Figure 8; Mytum and Webster 1989). Although their presence would certainly have slowed the progress of attackers, their defensive function has been questioned, and they may have had a more symbolic function. Having said that, the outside edge of chevaux-de-frise are usually well defined and approximately just within slingshot range from the main defensive bank, indicating that they did, indeed, have some form of defensive role.

As they are most commonly found in association with the castros of northern Iberia, many writers have suggested that this form of defence originated in that part of the world. Some of the best examples, however, are found in Ireland. The chevaux-de-frise around the stone fort perched on the edge of the high sea cliffs at Dun Aenghus, Inishmore, Co. Galway, is the most dramatic and most often quoted example.

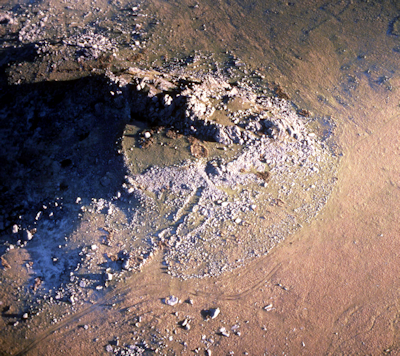

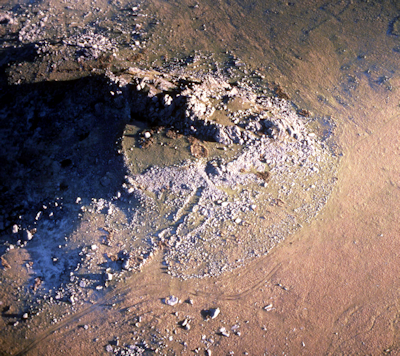

Five examples are known from Wales, including the only example found by excavation, at Castell Henllys in Pembrokeshire (Figures 14 and 15). This example is instructive for several reasons: as the upright stones were simply pushed into topsoil, construction would have been rapid and possibly only intended to be temporary; it was built in the 4th-3rd centuries BC; the upright stones only survived because they had been buried beneath a later defensive bank. It is clear that chevaux-de-frise are vulnerable, and it is noteworthy that most examples survive in landscapes that have not been cultivated or occupied since the Iron Age, or, as at Castell Henllys, they have been protected by later earthworks. Clearly many more examples may exist on unexcavated earthwork sites. Such an example is the coastal promontory fort at Black Scar in Pembrokeshire. This fort is slipping rapidly into the sea and wide fissures have opened up exposing sections of the banks and ditches, revealing the stones of a chevaux-de-frise beneath one of the banks.

In addition to stone, timber may also have been used. This material is more vulnerable than stone, and is more difficult to detect archaeologically, but isolated examples from France and Germany point to widespread use of this type of material, and indeed to a more widespread use of chevaux-de-frise.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.