Interaction between the native population and the Roman army is almost always seen purely in terms of how the garrison of any area will have interfaced with the local population there, but there is also another side to the relationship. The legions were recruited exclusively from Roman citizens (the only exception made was that if existing legionaries with non-citizen partners had sons, they too would be granted citizenship if they joined up). However, the army also contained many units of auxiliary troops who were recruited from the non-citizen subjects of the empire. The usual pattern with a recently subjugated province was to form units out of particular ethnic groupings who were sent to serve in other provinces, under officers who were Roman citizens, but fighting in the manner traditional for their ethnic group. We have no evidence for units created specifically out of the Silurian tribe, but we do know that there were units of Britons mainly serving on the Danube frontier. This was a way not only of obtaining troops for the army, but also reducing the risk of insurrection in their home provinces by removing the most energetic and enterprising young men and getting them used to the Roman way of life. The Silures in particular would have been a prime target for such recruitment, since they had a reputation for being fierce and warlike. As time went on, the majority of units stopped recruiting from their original ethnic groups (unless these had a particular military specialisation), and accepted recruits from closer to hand.

Auxiliary troops signed on for a period of 25 years; after that, the survivors would retire with Roman citizenship and a golden handshake in money or land. They could now return home if they wished. Some men stayed on near the forts where they had been posted (and where they would have had friends and possibly partners), particularly if the journey back would have been long or difficult. However, others would have gone back to their family homes with an increase in status and wealth, literate, and accustomed to living in Roman-style accommodation and buying Roman consumer goods. This is one possible reason why we can distinguish farmsteads with very different levels of pottery and metalwork and different types of building style.

Recent research in the Netherlands has drawn attention to the territory of the Batavi, who supplied specialist amphibious troops to the Roman army. Researchers have found a surprisingly high proportion of seal-boxes on rural sites with long-houses built in a tradition that goes back to the pre-Roman period, and it is suggested that they were attached to letters sent by serving soldiers to their families (but see Andrews 2013 for an alternative use). This contrasts with much lower proportions of seal-boxes on rural sites of the neighbouring tribes. If seal-boxes represent receiving letters, the styli used to write on wax tablets could represent the other side of the correspondence (Derks and Roymans 2002).

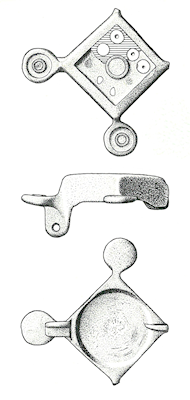

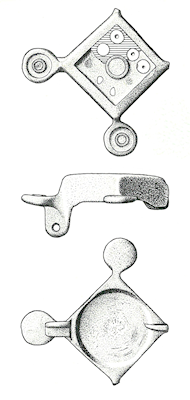

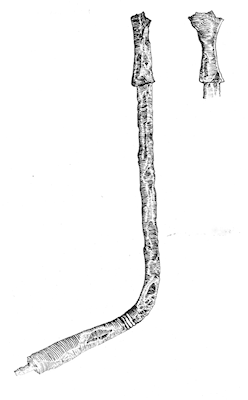

Can we distinguish similar patterns among the Silures? We are hampered in doing so by the very small number of sites that have been excavated, but there is evidence to suggest that this could be a useful method of approach. A seal-box has been found at the Caerwent Quarry site at Caldicot (Figure A), and two others have been found by metal detectorists on otherwise unknown rural sites. Styli have come from Biglis (Figure B), Mynydd Bychan and Whitton. There was also a fragment of an iron pen-nib from the Porthkerry Bulwarks, which may be of Roman date. With the exception of Whitton in its later phases, these sites fall into the Batavian pattern of settlements of traditional buildings. Similar items have also been found at sites in North and Mid Wales.

Finds have also been made on rural sites (such as Whitton) of items of military equipment. The usual assumption in the past is that these must have been lost by members of the garrison of the nearest forts, but it is also possible that they were dropped by inhabitants who had themselves served in the army.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.